These Steep Woods and Lofty Cliffs

These Steep Woods and Lofty Cliffs

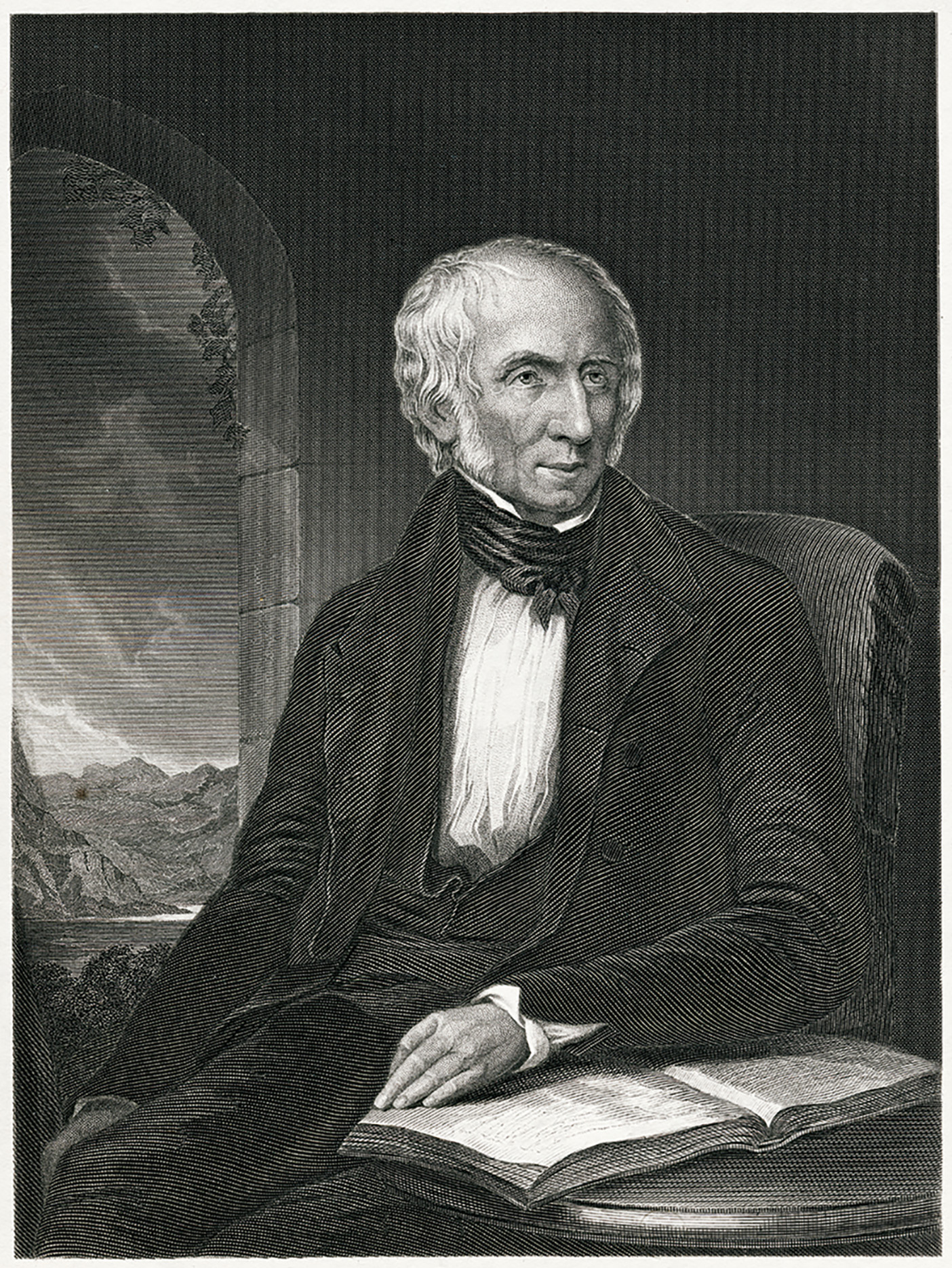

A formal relationship with the Wordsworth Trust takes hundreds of BYU students each year into the heart of William Wordsworth’s Lake District.

By Edward L. Carter in the Winter 2015 Issue

Photography by Mark A. Philbrick (BA ’75)

The first that died was sister Jane;

In bed she moaning lay,

Till God released her of her pain;

And then she went away.

In the parlor of an English cottage on a rainy summer evening, sisters Kristen E. (BS ’12) and Rebecca A. Shuel (’15) stood in the midst of 20 classmates from the BYU London Study Abroad, their faces illuminated by flickering candlelight. On this 2012 visit to Dove Cottage, the historic home of William Wordsworth in the Lake District village of Grasmere, the two recited the poet’s “We Are Seven,” which depicts a conversation between an 8-year-old “cottage girl” and the narrator, who, passing through town, inquires about the size of the girl’s family. She replies that there are seven children, then explains their whereabouts.

So in the churchyard she was laid;

And, when the grass was dry,

Together round her grave we played,

My brother John and I.

The poem was first published in 1798 as part of Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads, for which the poets are credited with helping initiate the Romantic period of English literature. As a complement to Coleridge’s poems on supernatural subjects, Wordsworth based his poems in themes of nature and human relationships, using the language of common people.

And when the ground was white with snow

And I could run and slide,

My brother John was forced to go,

And he lies by her side.

To the narrator’s protestation that “ye are only five,” the cottage girl insists: “O master! we are seven.”

As the Shuel sisters recited the lines, their voices filled with emotion and they paused as they considered the words. “I really felt a connection with this young girl,” Rebecca says. The Shuels’ own sister had passed away at age 15 in 2007, and since that time they had struggled to answer the question of how many siblings they have.

Listening to the Shuels that night was Jeff Cowton, curator of the Wordsworth Trust, which administers not only Dove Cottage but also the adjacent Wordsworth museum and research center. As a trust staff member for 30 years, he has helped host hundreds of thousands of visitors, but he says this BYU group’s visit—with the emotional rendering of “We Are Seven”—stands out.

“[Wordsworth] takes the condition of the human heart and the human experience, and he helps us to share that with others,” Cowton says of the poet’s influence on readers. “As he said, the purpose of his poems are to make us think, see, and feel.”

With their focus on nature, spirituality, and human relationships, Wordsworth’s works have long resonated with Latter-day Saint audiences, and poems like “Ode: Intimations of Immortality” (“Trailing clouds of glory do we come / From God, who is our home: / Heaven lies about us in our infancy!”) are often quoted in general conference.

“Wordsworth thinks into the heart as well as any poet,” says English literature professor Paul A. Westover (BA ’98, MA ’02). “He puts his finger on the essentials of thought and feeling in ways that make him a poet to grow up with. He’s great when you first meet him, but somehow he gets better as you read him over time.”

BYU Study Abroad students hiking away from William Wordsworth’s home. They are surrounded by grass and flowers alongside the trail.

While visiting the historic home of William Wordsworth, BYU study abroad groups explore the village of Grasmere and hike in the England’s Lake District National Park.

For I have learned

To look on nature, not as in the hour

Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes

The still, sad music of humanity,

Nor harsh nor grating, though of ample power

To chasten and subdue.

—from “Tintern Abbey”

To deepen student understanding of Wordsworth, BYU faculty have cultivated a relationship with the Wordsworth Trust for some 40 years, beginning with the efforts of now-retired English professor Gordon K. Thomas (BA ’59), who first took students to Grasmere in the 1970s. In 2011 English faculty Nicholas A. Mason (BA ’93, MA ’95) and Westover brought three students along on a research trip to the trust’s archive, which Mason calls the most significant author-based archive in the United Kingdom, housing 90 percent of Wordsworth’s original manuscripts.

During that visit Westover and Mason, who was scheduled to direct two London Centre programs in 2012, discussed with Crowton and trust director Michael McGregor ways to formalize the relationship between BYU and the trust and make it a standard part of the London Centre experience. They drew up a Lake District experience that would allow the students to explore the crags, fells, and lakes that inspired Wordsworth; enjoy a 19th-century dinner in Dove Cottage; and have unparalleled access to the archive’s rare books and manuscripts, which include the well-known journals of William Wordsworth’s sister, Dorothy, who lived with Wordsworth at Dove Cottage.

They also created an ongoing paid internship for BYU students to work at the trust for up to a semester at a time, bringing three English majors and one student employee from BYU’s library each year. BYU students prepare for these internships by spending time in the Harold B. Lee Library’s L. Tom Perry Special Collections, which has a robust collection of Wordsworth materials. At the trust they take on a wide variety of responsibilities.

Well pleased to recognise

In nature and the language of the sense,

The anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse,

The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul

Of all my moral being.

—from “Tintern Abbey”

English major Shane R. Peterson’s (’15) summer 2014 internship included working with handwritten Wordsworth letters, creating posters for an exhibit, and helping host a commemorative event. During her internship in winter 2014, Madison E. Mackey (BA ’14) came to know the archive collection well enough to guide a visiting PhD student who was researching original manuscripts.

Cowton empowered intern Elise M. Petersen (’15) to design displays for the Wordsworth Museum and develop and lead workshops for visiting student groups.

“It was absolutely terrifying the first time I had to do it,” Petersen says, “but after several groups, I found that I really loved it.”

Inspired by that experience and with the encouragement and mentoring of Cowton and others, Petersen is now directing her attention toward graduate studies with the goal of becoming a professor and researcher.

Nature never did betray

The heart that loved her; ’tis her privilege,

Through all the years of this our life, to lead

From joy to joy.

—from “Tintern Abbey”

In addition to the interns, more than 250 BYU students have now benefitted from the university’s unique relationship with the Wordsworth Trust. English professor Frank Q. Christianson (BA ’94, MA ’96), who was the Shuels’ professor on the 2012 trip to Grasmere, says the relationship “crystalizes the ideal of experiential learning more than any other single thing we do. It’s academic; it’s grounded in the archive; it’s site-specific—you can’t do it from Provo. Because Wordsworth’s art in particular is so connected to the landscape, it does make a difference to actually be in that place. The landscape is incredible. It’s inspiring and transforming.”

Elise Petersen says the experience has influenced the way she sees the world around her. On a recent hike to Squaw Peak above Provo’s Rock Canyon, Petersen reached a serene mountain meadow and recalled Wordsworth’s call for natural simplicity in “The World Is Too Much with Us”:

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers:

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

And when she struggles to describe the natural grandeur of the Lake District and rural beauty of Grasmere—its narrow, winding main road, stone fences, abundant greenery, and historic homes—she remembers that the answer is simple. All she has to do is invite her listener to read Wordsworth.