Stellar Alumni

In the Fall 2025 Issue

In his landmark 1975 centennial address, “The Second Century of Brigham Young University,” President Spencer W. Kimball set forth his vision for BYU to become “the fully anointed university of the Lord about which so much has been spoken in the past.”

And he expressed his hopeful expectation that out of such a university there would “rise brilliant stars in [the arts] and in all the scholarly graces. This university can be the refining host for many such individuals who will touch men and women the world over long after they have left this campus.”

And so it is. Having been refined and set ablaze in their disciplines and faith at BYU, alumni go forth prepared to spread light in ways large and small in their communities, congregations, and families.

Here we pluck from the BYU firmament 10 “brilliant stars” who shine bright for the benefit of the world.

Serving the Write Way

Allyson Braithwaite Condie (BA ’01), Novelist and BYU English Professor

Long before Ally Condie knew how to write, she was crafting stories, dictating them to her babysitter so she could share them with her parents. Now she’s not only a prolific bestselling author, but she’s also a mentor to aspiring writers at BYU and beyond.

“I realize how much we have in common,” she says, reflecting on the young readers and writers she meets when she travels. “You know, kids in New York and kids in Utah have many of the same concerns and joys.”

Joining the Church as a youth and being one of only two members in her family, Condie felt an overwhelming sense of “belonging and community” when she arrived at BYU. She not only gained a passion for teaching as an English teaching major but also learned to see people through a new lens. “I think maybe the biggest thing . . . BYU solidified in me is that people are good,” she says.

This belief in the goodness of people is at the heart of Condie’s work. In her Matched series, for example, Condie says readers have commented that there doesn’t seem to be any enemy in the story other than the society against which the main character is rebelling. That’s because, Condie explains, “by and large, people in the world are good and they’re trying to do good things.”

“I feel like in this world, you’re lucky to have one job that you love, and I have three: mother, writer, teacher.”

—Ally Condie

Condie’s Matched series was a New York Times bestseller, and her middle grade novel Summerlost is an Edgar Allen Poe Award finalist. For her, though, the most joy comes from her readers, not from accolades. “Because I was a teacher and I worked with reluctant readers, every time I get a note or an email or a kid comes up and tells me, ‘Hey, I didn’t like reading until I read your book, and now I like reading,’ that’s the biggest honor.” Along with continuing to publish children’s books, Condie is expanding her craft into the realm of adult novels with her latest book, The Unwedding, a murder mystery.

Writing isn’t Condie’s only passion. “My kids are my top priority,” she says. She also serves in her ward’s Relief Society presidency and is the founder and director of WriteOut Foundation, a nonprofit that organizes author workshops in areas that might otherwise go unnoticed. “I grew up in a rural Utah community, and we never saw an author. We didn’t know that was a career path,” she explains. “So I try to bring writers to those communities.”

Last year Condie returned to BYU as a creative writing professor, which she sees as a chance to support and encourage the next generation of storytellers. “I am curious about you,” she says to her students. “I am interested in your writing. I want you to take this to the next level, and [I want to] help scaffold you.”

“I feel like in this world, you’re lucky to have one job that you love,” Condie says, “and I have three: mother, writer, teacher.” • By Olivia C. Flynn (’26)

Where the Needs Are

Nicolette Broby (MS ’17), Rural Family and Emergency Nurse Practitioner

Disaster seems to follow Nicki Broby. She was a missionary in Washington, DC, during the 9/11 attacks—volunteering with the Red Cross in the aftermath is part of what inspired her to study nursing. Later Broby was cheering on a friend at the Boston Marathon when the 2013 bombing happened. “I’ve done CPR on an airplane and mouth-to-mouth in Sunday School,” she recalls.

On her first assignment as a traveling nurse practitioner (NP) in remote Alaskan villages, a large earthquake hit in the middle of the night. As Broby, the only medical personnel in the area, helped evacuate sleepy residents in the wake of a tsunami warning, she remembered the source of her courage when disaster strikes.

“You can’t separate the Spirit from medicine,” says Broby, who continues to work months-long stints in Alaskan villages, where she often acts as 911 operator, ambulance driver, and pharmacy tech. When she’s not in Alaska, she works part-time at a Yuma, Arizona, ER and for the national disaster medical system. “God gives us a lot of courage to go into uncomfortable situations. And in my work, there’s a lot of uncomfortable situations.”

“God gives us a lot of courage to go into uncomfortable situations. And in my work, there’s a lot of uncomfortable situations.”

—Nicky Broby

Five years after earning a nursing degree at Arizona State, Broby volunteered on a navy ship in South America and the Caribbean. On the flight home, she pled with the Lord to reveal her next steps and felt prompted to move to Utah to become an NP. Confused when she wasn’t accepted into the University of Utah’s program, Broby bloomed where she was planted. She got a job in the U’s ER, served a part-time medical mission, and mentored nursing students. While working with BYU students and faculty, she felt inspired to apply for a master’s there—and she was accepted.

At BYU Broby’s thesis work on medical disaster relief included traveling the world to interview volunteer organizations and visit refugee camps. Her completed work was published in a journal and presented to the Church’s emergency response department. The knowledge served her well later while working in hot spots in Northeastern Arizona during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Her professors helped her see nursing as a kind of Christlike ministering.

Broby draws on this insight every day, such as when she sat at the bedside of an Alaskan woman diagnosed with cancer who decided to let nature take its course at home instead of leaving her village to seek treatment. And just recently when a homeless man turned up yet again in the ER. “I asked, ‘Where’s your beautiful dog?’ And he said the dog had died. We talked for a little bit while he grieved, and I think it helped him know we cared,” Broby says. “This is a child of God too. That’s the difference between just doing your job and ministering.”

Splitting her time between Arizona and Alaska, Broby says she gets “weather whiplash.” But she’s drawn to these extremes. “There are enormous needs in Alaska; there are enormous needs on the border of Mexico. And I love being where the needs are.” • By Sara Smith Atwood (BA ’10, MA ’15)

Casting Light

McKay A. Coppins (’25), Staff Writer for The Atlantic Magazine

When The Atlantic editor, Jeff Goldberg, asked him to write a feature story about The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, staff writer McKay Coppins hesitated. His beat was politics—he’d hoped to avoid becoming the “token Mormon writer.” And Coppins worried his personal beliefs would undermine journalistic reporting. Then Goldberg spelled it out: “If you won’t do it, I’ll find another writer.”

Coppins was the only Latter-day Saint at the magazine—really, the only one on the stage of big national media. If someone was going to write a piece on the Church, he realized it might as well be him.

“I became known among the traveling press corps as the ‘Mormon Wikipedia.’”

—McKay Coppins

“Don’t try to hide from your readers how this has shaped your life,” Goldberg told him. “The Most American Religion” became an authentic and unflinching study of the Church’s past and present through the eyes of a believer, taking readers from the history of polygamy to karaoke night at the Coppinses’ former branch in Brooklyn. “It had the texture of lived religion woven through it,” says Coppins. Hundreds of readers from different religious traditions wrote in sharing how the article resonated with them.

Leaving BYU’s journalism program at the tail end of the recession, Coppins and his wife, Suzanne “Annie” Schmidt Coppins (BS ’11), bought one-way tickets to New York City so Coppins could complete an internship at Newsweek.

He was there during the “Mormon Moment,” contributing to a Newsweek cover story featuring Mitt Romney’s (BA ’71) head imposed over a dancing missionary from The Book of Mormon musical. “I was in a good position to help demystify Mormonism,” says Coppins, who later wrote explainers on topics like baptism for the dead for BuzzFeed. Faith and his interest in politics merged as Coppins broke the news of Jon Huntsman’s presidential bid and covered Romney’s 2012 campaign.

“I became known among the traveling press corps as the ‘Mormon Wikipedia’ because the other reporters could just ask me any question about Romney’s faith,” Coppins recalls. He wished then—and still does—for backup. “Every time I speak to BYU students, I always beg them to come join me in national media.”

In writing profiles of public figures, including a bestselling biography of Romney, Coppins draws on lessons learned at BYU. “We are all ultimately children of God,” he says. “People are complex, and they make good and bad decisions. . . . People in public life are wrestling with the tension between their ambitions and their conscience much more than most people would recognize.”

Coppins admits to feeling those tensions in his own life, weighing what’s best for his career against what he believes is right. In looking to what’s next—more books, a podcast, producing a Netflix docuseries—he remembers the fire he felt as a young reporter: “I want to do journalism that makes a difference. I want my work to cast light and not heat.” • By Sara Smith Atwood (BA ’10, MA ’15)

Managing the Business of Life

Carine Strom Clark (BA ’87, MBA ’93), Entrepreneur and Chief Executive Officer of First Colony Mortgage

“I want to build things that work beautifully without me, because I already know I’m going to die,” says entrepreneur, business executive, and investor Carine Clark.

In 2012 Clark received a life-clarifying diagnosis: stage 3 ovarian cancer with only a 20 percent chance of beating it. Her 9-year-old son’s plea was simple: “Mom, don’t die.”

“Look, buddy, I can’t promise you that,” she told him. “But I can promise you that I will teach you what it means to stand up to something just awful with guts, grace, tenacity, and grit.”

Clark says, “The gift that cancer gives you is that you live differently.” Not wanting to “waste the cancer,” she quit watching TV and began to build what she dubbed “an MLM of temple work.” She recruited youth for baptisms, involved parents and missionaries, and passed names to friends. The result? She has arranged ordinances for more than 8,400 ancestors—so far.

Currently CEO of First Colony Mortgage, Clark looks for ways to reduce friction in the home-buying process. She serves on boards for the Governor’s Office of Economic Opportunity, Silicon Slopes, and the 2034 Olympics, while fundraising for the Huntsman Cancer Institute. “There’s nothing really special about me,” she says. “I just know what I have to do, and I just do it.”

“Any time BYU calls me, I will do whatever they need to help the young people.”

—Carine Clark

Clark says BYU’s MBA was “the perfect program for me: . . . a degree for managing the business of my life, not just to do well in business.” As a student she started networking, inviting a professor to lunch. That professor invited her to a recruiting function, and since then she says she’s been trying to get more women to get MBAs.

While she works miles away from campus, Clark says she never left BYU. “I’m on a mission to help young people get their advanced degrees because it does make a difference,” she says. “Any time BYU calls me, I will do whatever they need to help the young people.”

Her message to students? “Choose courage over comfort. The universe really does reward the brave. Heavenly Father wants us to be peaceful warriors, willing to stand up and not afraid to stand alone.”

Clark encourages fellow BYU grads to be mentors. “A lot of young people can’t be what they can’t see,” she says, and alumni are uniquely qualified to help. “If you just love them, . . . there’d be no holes in the fabric of our community worldwide.”

She also shares the secret to her world. “The only way I can make it through cancer, infertility, job and relationship struggles, is to do my very best and trust God. The Atonement did pay for everything. We don’t have to have everything figured out, just the next step.” • By Michael R. Walker (BA ’90)

Changing the World

Jared M. Spataro (BS ’98), Chief Marketing Officer for AI at Work—Microsoft

Jared Spataro left BYU fired up to change the world. “[I had] this burning, relentless, unstoppable desire to get out there and, as much as I could, make the world a better place,” he recalls. “Not . . . become-president-of-the-United- States-change-the-world,” he clarifies. “I just wanted to change the world as I could within my circle of influence.”

And Spataro has left his mark. Professionally, it’s one he observes as he walks airplane aisles. As a Microsoft executive who has helped develop products ranging from Office to Teams to the company’s current initiatives with AI, he says it’s fun to look over shoulders and “see everyone using the things I work on.” His work literally affects billions—“how they communicate, how they work, how they get things done, how they invent, how they run businesses.”

And yet, big as that influence may be, Spataro, who was recently called as an area seventy for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, says he finds just as much meaning serving at home and in his community.

Growing up in a military family, Spataro moved all over, including spending two tours in Cold War Germany and time in the US South. His experiences, including membership in tiny branches and struggling wards, gave him insights into the challenges of the world and the Church.

“When I let God do His work in my life, I’m always happier and more successful and more at peace.”

—Jared Spataro

Against that backdrop, he says, “my freshman year at BYU was magical. . . . It was the fun I had looked for all my life with people doing good things.” He says he had a “classic BYU experience”—studying hard (computer science), pausing to serve the Lord (in New Zealand, Chinese speaking), teaching at the MTC, getting married (to Kimberly Kirby Spataro [BS ’95]), and living in Wymount.

Leaving BYU, the Spataros jumped right into an adventure—taking a job in Beijing. As Latter-day Saints in the heart of communist China, they couldn’t preach their faith. But they found they could still reflect Christ’s light through service.

After adding an MBA from MIT and settling into corporate life, Spataro says he has sometimes felt like exiled Bible figures—Joseph in Egypt or Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed-nego in Babylon. “You have to determine how you’re going to live” in the business world, he says. “You have to be willing to sacrifice” worldly attainment when it conflicts with your values.

Even so, Spataro sees God’s presence in all facets of his life—including his employment. God seems to tell him: “Everything I ask you to do is my work—with your family, at Microsoft, in your callings. All of it is my work—as long as you do it my way, as long as you pursue it for my ends and not yours.”

“When I let God do His work in my life,” Spataro says, “I’m always happier and more successful and more at peace.” • By Peter B. Gardner (BA 98, MA ’04, MBA ’22)

The Little Light

Jennifer Moorman Beech (BS ’95), Elementary School Teacher and BYU Education Society National Alumni Board Member

With just three weeks left in the school year, a school administrator brought a young Ukrainian boy and his mother to Jennifer Beech’s pre-K classroom in Plano, Texas. While her husband was in Ukraine fighting in the war, this mother was trying to navigate a foreign place, school system, and language. The mother’s face, laden with fear, struck Beech deeply. When she told the school administrator how hard it was to watch them navigate this new territory, “ripped away from [their] family and . . . homeland,” he replied, “That’s why you’re his teacher. You’re going to take this seriously and give him everything he needs.”

And that’s just what Beech did. Determined to bring light and direction to both the student and his mother, she thought, “I have three weeks to make a difference,” and got to work.

As she champions literacy in students like this Ukrainian boy, Beech measures success with a question: “Does your face light up when you see me?”

Beech learned about sharing light as an education student at BYU. Moving from a small town in Texas to the much larger Provo, she quickly collected fond memories on campus. “It’s like baptism by fire to be thrown into such a spiritual place in which every class has a connection to the gospel, and that was a totally new way of learning for me,” she says.

“The Lord loves literacy, and the Lord loves education.”

—Jennifer Beech

One class lecture stands out: When professor A. LeGrand “Buddy” Richards (BS ’75, PhD ’82) asked if anyone knew the song “This Little Light of Mine,” Beech was the only one in a class of 150 students to raise her hand, having grown up singing it. When Richards asked her to sing the song in front of the class, she was terrified but let her voice ring out anyway.

Learning to let her light shine became central to Beech’s BYU experience, she says. “It refined me, and now I try to connect the Savior and my Heavenly Father to everything I do.”

Beech has taught students of many backgrounds throughout the years as a teacher of young students. Currently she teaches pre-kindergarten, and many of her students are immigrants who speak Middle Eastern languages.

Beech also teaches as a service missionary for a pilot program that supports literacy among English language learners. As part of her service, Beech has taught reading and writing to people in Mexico and Zimbabwe. Although they are in distant countries from Beech, she calls them her neighbors.

In her work and service, Beech helps spread the Lord’s light. “The Lord loves literacy, and the Lord loves education,” she says. “Being a little teeny part of that is powerful.” • By Sierra K. Martin (’26)

Medicine and Meaning

Tyler P. Johnson (BA ’05), Oncologist, Educator, Writer, and Podcaster

What Tyler Johnson does is hard to pin down. By trade, he’s a practicing oncologist at Stanford Medicine. But he also devotes significant professional time to teaching and mentoring medical students and residents. He cohosts the award-winning podcast The Doctor’s Art. And he’s a prolific writer and thinker who serves on the editorial boards for BYU Studies and Wayfare.

This diversity of interests and output has roots in his time at BYU. He says he was drawn to Provo in part by the idea of BYU as a place where “the spiritual part of you and the intellectual part [could] be in conversation with each other.” For the premed student and American studies major, the scientific, humane, and spiritual bled together at BYU.

Some of Johnson’s most spiritual educational experiences came in classes that weren’t overtly religious. In Studies in the American Experience, Professor Neil L. York (BA ’73, MA ’75) helped his students excavate the underpinnings of democracy, America, and freedom—“a deeply and beautifully spiritual experience,” says Johnson. His copy of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America from the class is “underlined and annotated like it’s my scriptures,” he says.

Inspired by BYU teachers and mentors like York, Johnson says, “all good scholarship is a form of discipleship.”

In Johnson’s medical practice, his foundation in the humanities and big ideas has informed his approach.

“Everything I do is about the person in front of me, . . . trying to bring some degree of light, . . . a measure of love.”

—Tyler Johnson

Medicine “can become technocratic and robotic if we’re not grounded in some of those bigger questions,” Johnson notes. Although his work involves technical processes like chemotherapy dosing and reading CT scans, ultimately, he says, “everything I do is about the person in front of me.” It’s about “trying to bring some degree of light, . . . a measure of love, to those endeavors.”

In their podcast Johnson and his cohost, Henry Bair, set out to address today’s epidemic of burnout, disillusionment, and depression afflicting the medical professions. Through probing interviews with care providers, they explore what it means to build meaning in a career and in life. Although many of the guests are not religious, Johnson says the conversations tend to wind around to the mystery and sanctity inherent in caring for suffering humans.

For Johnson, both his podcast and his writing are ways to explore big questions.

“I write like I sweat,” he says, calling writing the natural byproduct of his mental exertions. “It’s the way I work my way through questions that are on my mind.” It’s a conversation with other minds—past, present, and future—grappling with the same ideas.

Ever the doctor, Johnson says all such work is ultimately about finding and relieving human suffering. He calls engaging with the world to relieve pain a deeply Latter-day Saint idea. “There is a beauty and grace to trying to show up in the world.” • By Peter B. Gardner (BA ’98, MA ’04, MBA ’22)

Lessons in Arguing

Stephanie Hall Barclay (JD ’11), Georgetown Law Professor, Former US Supreme Court Law Clerk

I’d wanted to go to law school since I was 10,” says Stephanie Barclay, a Georgetown Law professor and codirector of the Georgetown Center for the Constitution. She’d seen a lawyer argue while representing her dad’s business. She thought it looked like fun and liked the idea of being paid to do it.

But what she learned at BYU’s J. Reuben Clark Law School changed her perspective on lawyering. “BYU Law emphasized being a different kind of lawyer, practicing law in light of the higher laws,” says Barclay. Speakers like President Dallin H. Oaks (BS ’54) and Elder Quentin L. Cook of the Quorum of the Twelve talked about using tools from law to build the kingdom. Inspired, Barclay worked for the Church’s legal department in Germany after her first year of law school, dealing with religious liberty issues in eastern Europe.

At BYU Law Barclay also learned the value of knowing when not to fight and when to tell a client certain legal pursuits are not worth it. As a kid, she says, “I had envisioned the law as being like a sword that you could run around and whack people with all the time. But law school was more like, ‘Well, here’s when you need to put your sword in the sheath. Now is a moment to be a peacemaker and help these parties reconcile.’”

“BYU alumni are well positioned to go out in the world and be firm on principles but to do so without being hard on people.”

—Stephanie Barclay

A particularly memorable lesson came while clerking for Judge N. Randy Smith (BS ’74, JD ’77), a BYU Law alum on the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Her team was writing a dissent and exchanging memos with the majority-opinion judge and his clerks. At one point the judge sent a memo accusing Judge Smith of inaccurate citations to the record. “I wrote a feisty memo back and took it to Judge Smith,” says Barclay, who remembers his gentle response: “This is a very well-written memo. Very persuasive. But we are not going to send it. Try again and draft a memo that is kinder and takes the tone of ‘We can see why you may have been confused about some citations. Thanks for wanting clarification. Here are some citations that we hope will add clarity. But if you think we’re still missing something, we’d love to talk.’”

Later, the majority judge called Smith to apologize for the first harsh memo and thanked him for the conciliatory memo they’d sent.

“I learned you can disagree vigorously and still be kind,” Barclay says. “BYU alumni are well positioned to go out in the world and be firm on principles but to do so without being hard on people—to be listeners and understand other perspectives. There’s just something about learning about the law in an environment where you share the fundamental knowledge that, at the end of the day, we are each beloved children of God who are worthy of love and dignity.” • By Andrew T. Bay (BA ’91, MA ’94)

From Products to People

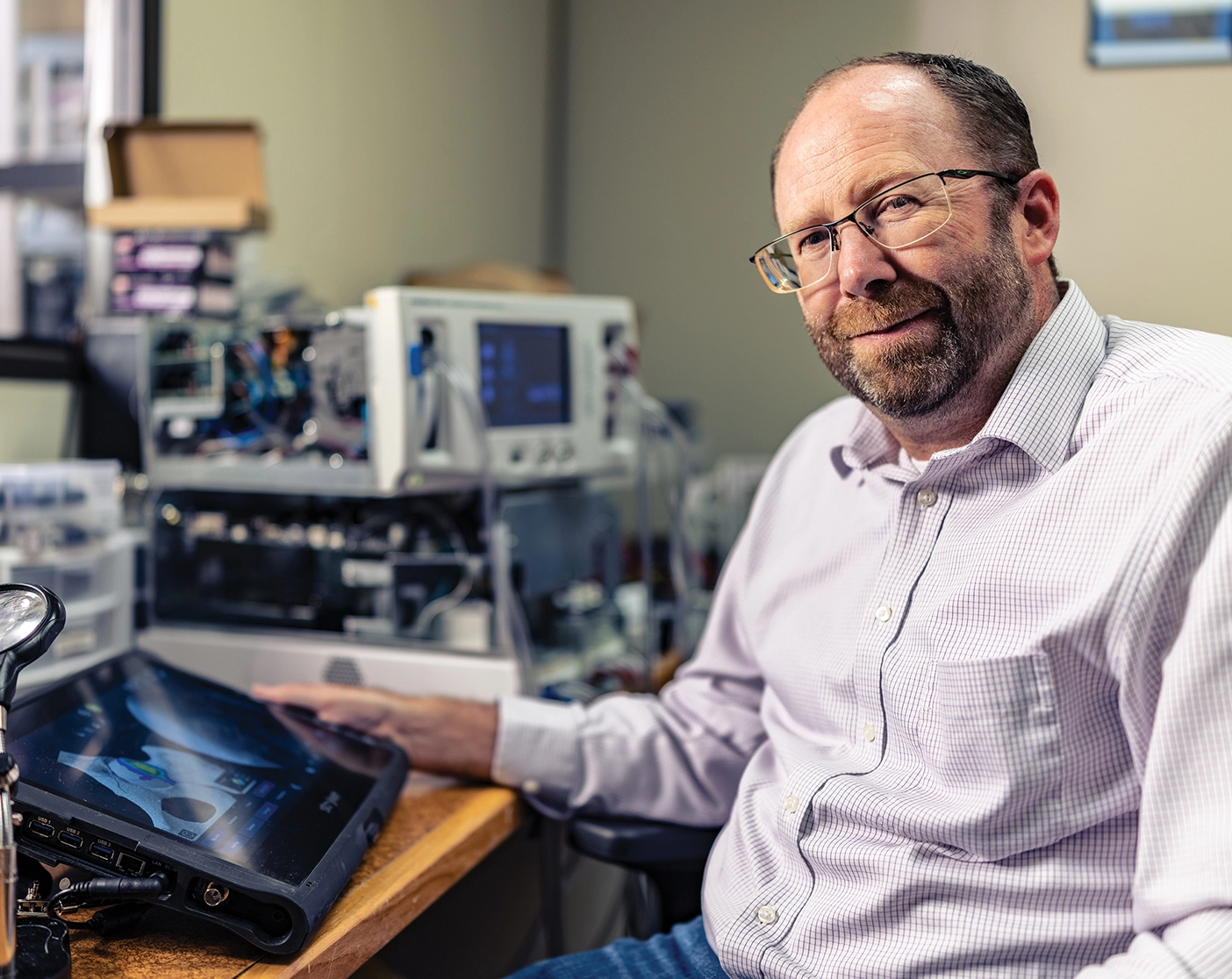

Brady L. Woolford (BS ’04, PhD ’09), Creator of Medical Devices

Not everyone gets to see the impact of their labors up close. BYU mechanical engineering grad Brady Woolford got just that opportunity when some of his family members had surgery using a system that he developed for Stryker, a medical device company.

The device, CrossFlow, is used to pump fluid into a joint space during surgery. A few years after it was successfully tested in Canada, surgeons used the device to operate on Woolford’s father (for a rotator cuff repair) and his son (for a knee procedure). “To be able to . . . watch that product work and know everything that went into [getting] it to work and just see it functioning as designed—it’s been really exciting,” says Woolford.

The experience echoes something Daniel Maynes, one of Woolford’s BYU professors, once said about a particularly difficult class: “I intend this class to challenge you because this is how you will really learn the principles and become an influential engineer. You are going to be designing the airplanes, cars, elevators, bicycles, and operating-room equipment that my family and I will use, and I want all of these products to be safe and to work as they are intended.”

“As a mentor, I love . . . being able to see the growth that can take place in an individual as they gain confidence in their skills.”

—Brady Woolford

“Sure enough,” says Woolford, “the class was challenging, but there was that purpose behind why, which really stuck with me, even now as I develop new medical devices.”

Woolford says that Maynes saw something in him that he did not then see in himself—the ability to focus on complicated problems and find solutions to them. That strength is reflected in what Woolford considers to be his approach to his work: “Just get it done.”

After adding a PhD at BYU, Woolford spent five years working in San Jose, California, developing numerous medical devices for Stryker. Eventually, Woolford returned to Utah to set up a satellite office for the company, where he continues that work. The move allowed him to return to BYU campus, where he helps students see their potential just as his BYU mentors did for him. From coaching engineering capstone classes and serving on the Mechanical Engineering Advisory Committee to working with the Student Innovator of the Year program, Woolford finds many ways to give back to his alma mater. “As a mentor, I love . . . being able to see the growth that can take place in an individual as they gain confidence in their skills and [are] able to seek out their own answers and solve problems,” he says.

His next mountain to climb? A shift in focus from products to people. “Up to this point, the mountain has been building products that are meaningful and impactful,” Woolford says. “Now, I think it’s more [about] building . . . groups and organizations that can have a more meaningful impact.” • By Sierra K. Martin (’26)

Going Forth, Reaching Back

Britlyn D. Orgill (BS ’11), Anesthesiologist and Cofounder of the BYU Medical Society

Britlyn Orgill is not just a star; she’s a supernova. An anesthesiologist and critical care physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, Orgill is not shy about reflecting the light of BYU as an alum, whether with a Cougars banner in her office or her stellar efforts to go forth and serve.

“We consecrate our time and talents,” Orgill says. “When you’re given a really great opportunity, how can you use it to bless other people?”

Orgill’s father is a professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and a plastic surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. As an undergrad Orgill gained experience in his lab, which enhanced her cancer research at BYU. “But I realized not everyone has that connection,” she says. “I felt like I had a responsibility to help give that.”

Later, as a resident at Harvard, she had a midnight conversation on the hospital floor with fellow BYU grad and Harvard resident Joshua D. Jaramillo (BA ’09). Together they cofounded the BYU Summer Premedical Research Internship Program, which arranges opportunities for 25–50 students each year to gain research experience at Harvard, Vanderbilt, Stanford, Duke, and other leading universities. Many alumni of the program eventually secure admission to top-tier medical schools.

“When you’re given a really great opportunity, how can you use it to bless other people?”

—Britlyn Orgill

This led to helping establish the BYU Medical Society, a nationwide network of BYU alumni in the medical field who open doors for BYU premed students.

BYU instilled a mindset of giving in Orgill that she’s carried with her. “In the lab I was in, there were students above me that were training me, and the expectation was that I would train the people behind me.”

As a stressed premed student herself, Orgill found her footing on the spiritual and social foundation of BYU. She balanced grueling study hours with enjoying Divine Comedy performances, going to devotionals, swimming in the Richards Building, and establishing spiritual habits she maintains to this day.

“I became more okay with being myself,” she says. “That peace, to be able to embrace my identity with the Church, is huge. I’m really grateful that I had that spiritual grounding.”

These days, Orgill performs once a month as a comedian at ComedySportz, organizes ugly sweater dances as a stake young women’s president in Boston, and plays the violin and piano at charity concerts to raise money for medical equipment in remote areas of the world.

Through the ups and downs of her demanding career, Orgill believes in enjoying life along the way. “I talked about the marshmallow experiment with my BYU interns, [the idea that] you’re going to get an extra marshmallow if you just wait. I always tell them, ‘You guys have waited already so long, you just start eating marshmallows as you go. You need to learn how to enjoy the journey.’” • By Jedidiah A. Flores (’26)

Feedback Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.