Imagine GPS directions being projected onto the road by smart glasses as you drive—or vehicles that do the driving for you. We’re one step closer to these future innovations, thanks to research led by BYU electrical-engineering professor S. Wood Chiang: his team has created the most power-efficient microchip in the world.

Tiny but mighty, microchips power our portable devices, transferring data and enabling things like video streaming on the go. We all want faster downloads, which requires faster microchips.

This poses a problem that circuit designers worldwide, like Chiang and his students, have been trying to solve for years. Increasing a microchip’s speed usually increases its power consumption, which in turn reduces battery life.

“We wanted to make sure that we were meeting speed [requirements] but keeping power down as much as possible,” says Eric L. Swindlehurst (BS ’15, PhD ’20), a recent PhD grad who worked in Chiang’s lab.

Together with researchers from National Chiao Tung University in Taiwan and UCLA, Chiang’s team took the lead in finding a solution. Their microchip, described in an article published in the prestigious Journal of Solid-State Circuits, uses 30 times less power than typical models operating at the same speed, 10 gigahertz. At this frequency, the BYU chip consumes 32 milliwatts; the chip in your phone uses about one watt.

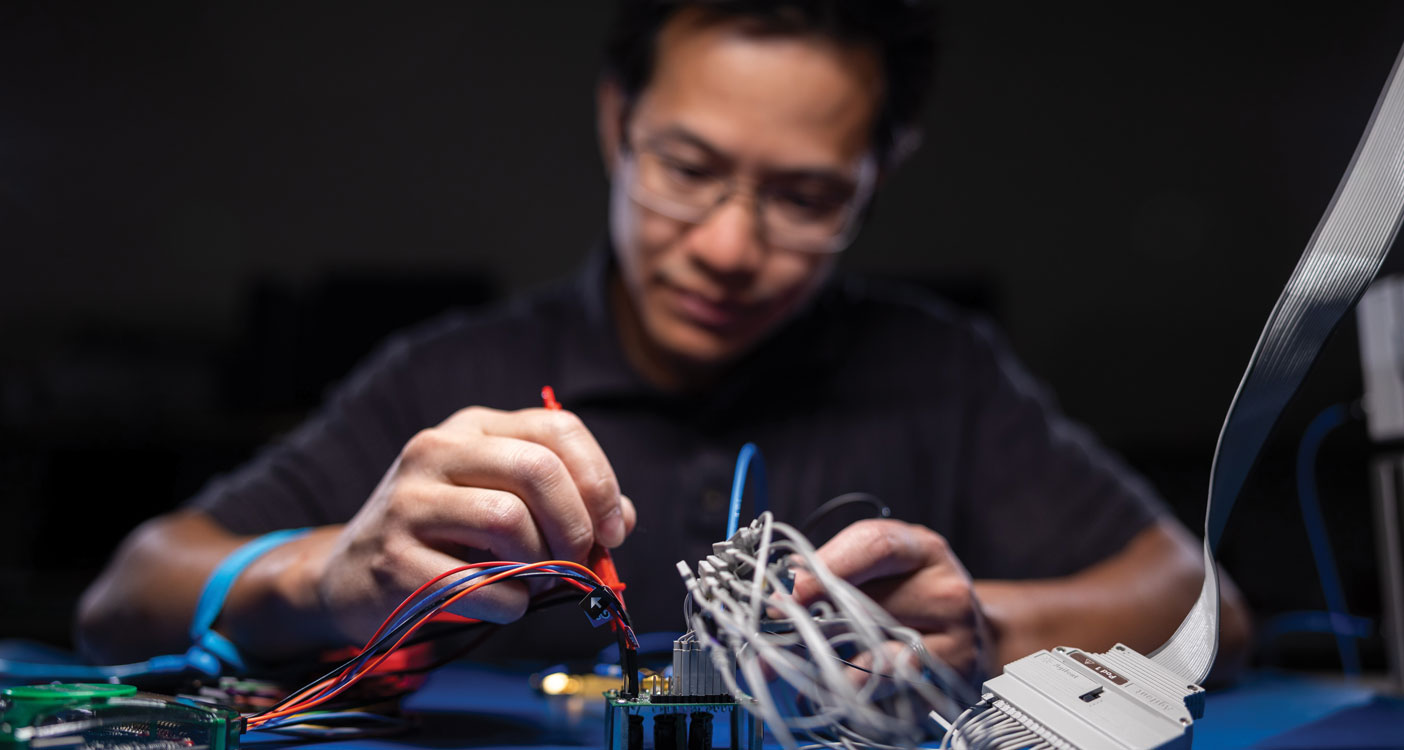

The BYU group worked specifically on the analog-to-digital converter (ADC), a sliver of silicone in the microchip about half the width of a strand of hair. The ADC converts analog signals from the air into digital signals that communicate with your device.

The ADC took four years to complete, including one year of high-stakes testing. “A microchip like this has thousands, even tens of thousands of connections,” Chiang explains. “If you were to mess up even one connection, . . . the whole thing would fall apart”—and delay the project by a year.

So when the microchip worked on the first try, it was a big deal. “As I’ve gone into industry, our chips go through three, four, or five iterations,” says Swindlehurst, who now works on automotive chips at Infineon Technologies.

In this industry, you’re always problem solving, says Swindlehurst. “But seeing all your hard work come to fruition . . . , you know that you’re contributing to the world at large.”