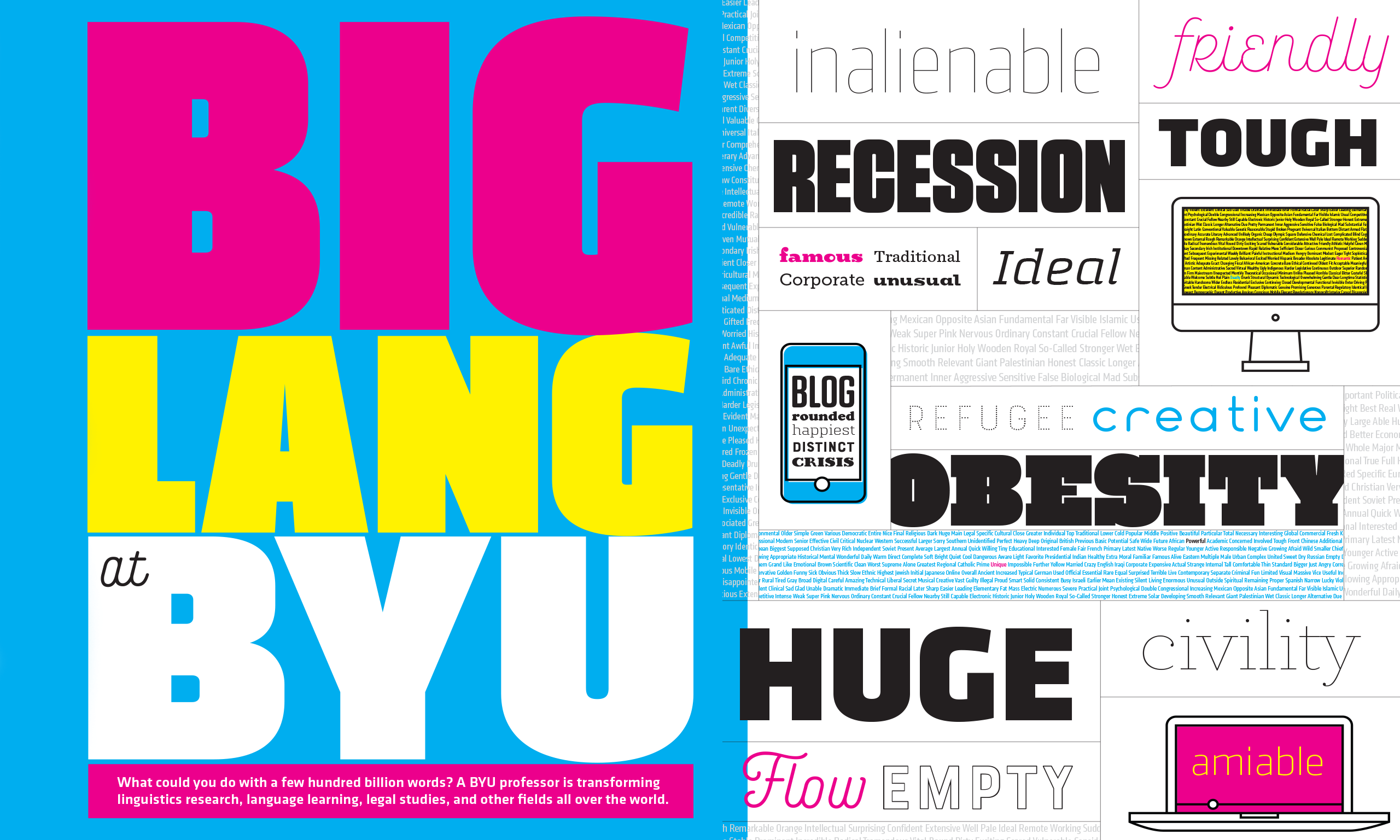

Big Lang at BYU

What could you do with a few hundred billion words? A BYU professor is transforming linguistics research, language learning, legal studies, and other fields all over the world.

By Amanda K. Fronk (BA ’09, MA ’14) in the Summer 2017 Issue

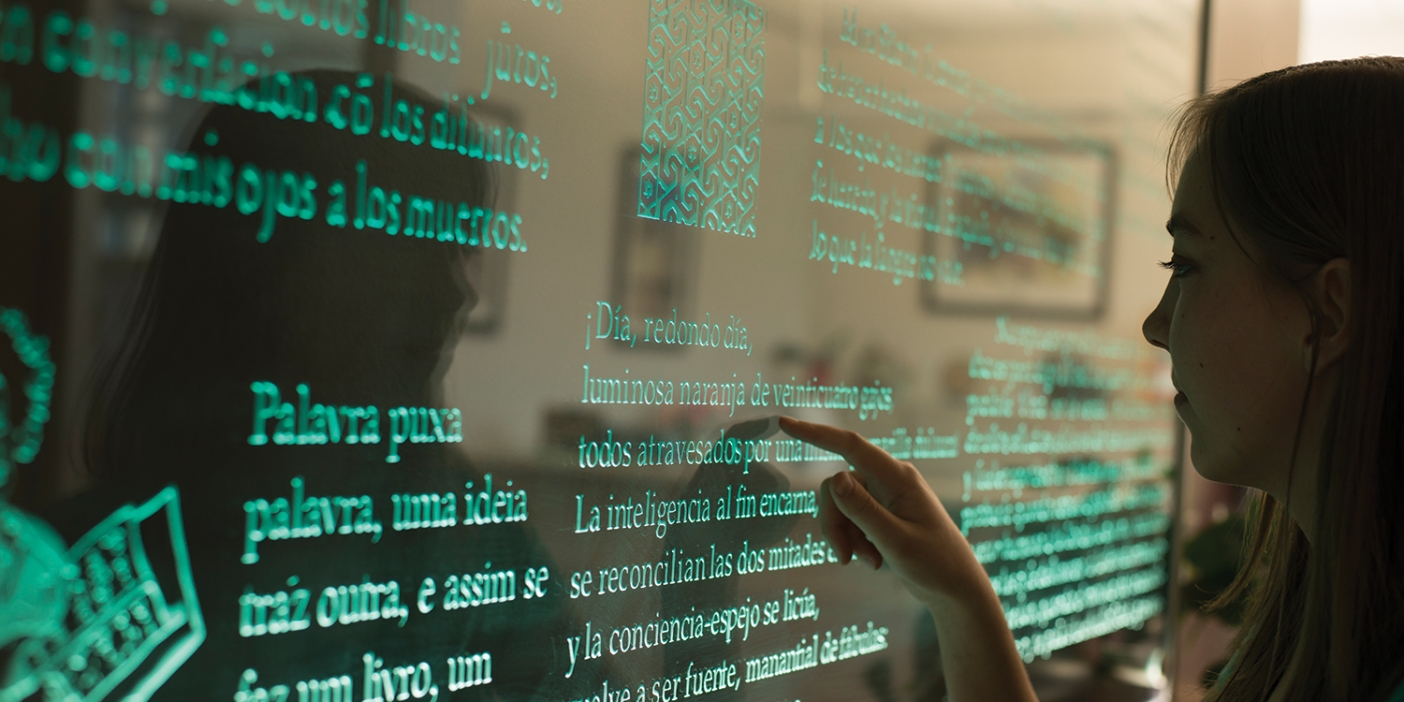

Every time your phone predicts your next word or converts your voice into text, a bit of technological magic is taking place. Unlike humans, the computer in your phone can’t rely on something sounding right. Instead, your phone depends on a huge batch of language data. That’s how it knows you mean “I’ll be right back” and not “I’ll be write back”—and a million other linguistic nuances that we non-computers take for granted.

The data backing all of this language processing is vital to tech companies like Apple and Samsung, and it just so happens that BYU is where they look to teach their machines to speak. When it comes to language and big data, BYU corpus linguist Mark E. Davies (BA ’86, MA ’89) is at the forefront.

Don’t get hung up on the Latin. A corpus (“body”) is just a massive searchable database of words—like Google but more refined—that provides a window into how language is used and changes over time and that can help untangle a plethora of linguistic conundrums. Davies is known worldwide in linguistic circles for building corpora (corpus’s fancy plural form). Outside of academia, his corpora are being used by the likes of Disney, the Oxford English Dictionary, and Netflix.

Davies’s 21 databases cover everything from British Parliament speeches to soap-opera scripts to every LDS general conference talk since 1851. The most used is the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), which catalogs half a billion words. But that’s just a drop in the bucket of the roughly 334.12 billion words in the corpora. And they’re constantly growing: one news-aggregating corpus gains 4–5 million words every day. “I’m constantly bumping right up against the limit of what technology will allow, but as it gets better, the corpora get larger,” says Davies.

While there are bigger corpora out there, BYU’s free databases are the most widely used. Dilworth B. Parkinson (BA ’75), a BYU Arabic professor who was inspired by Davies to develop a well-known Arabic corpus, says the interface of the BYU corpora makes the data easily accessible to anybody, not just “techy people.”

Another selling point for the BYU corpora is their curation. With the help of a computer, each word is tagged for its part of speech, genre, and the date and location of its source material. “Size is always important, but more important is being able to get that information,” says Davies. “Where is this grammatical construction, this phrase, [or] this word . . . used? In what countries? What time periods? Which genres?”

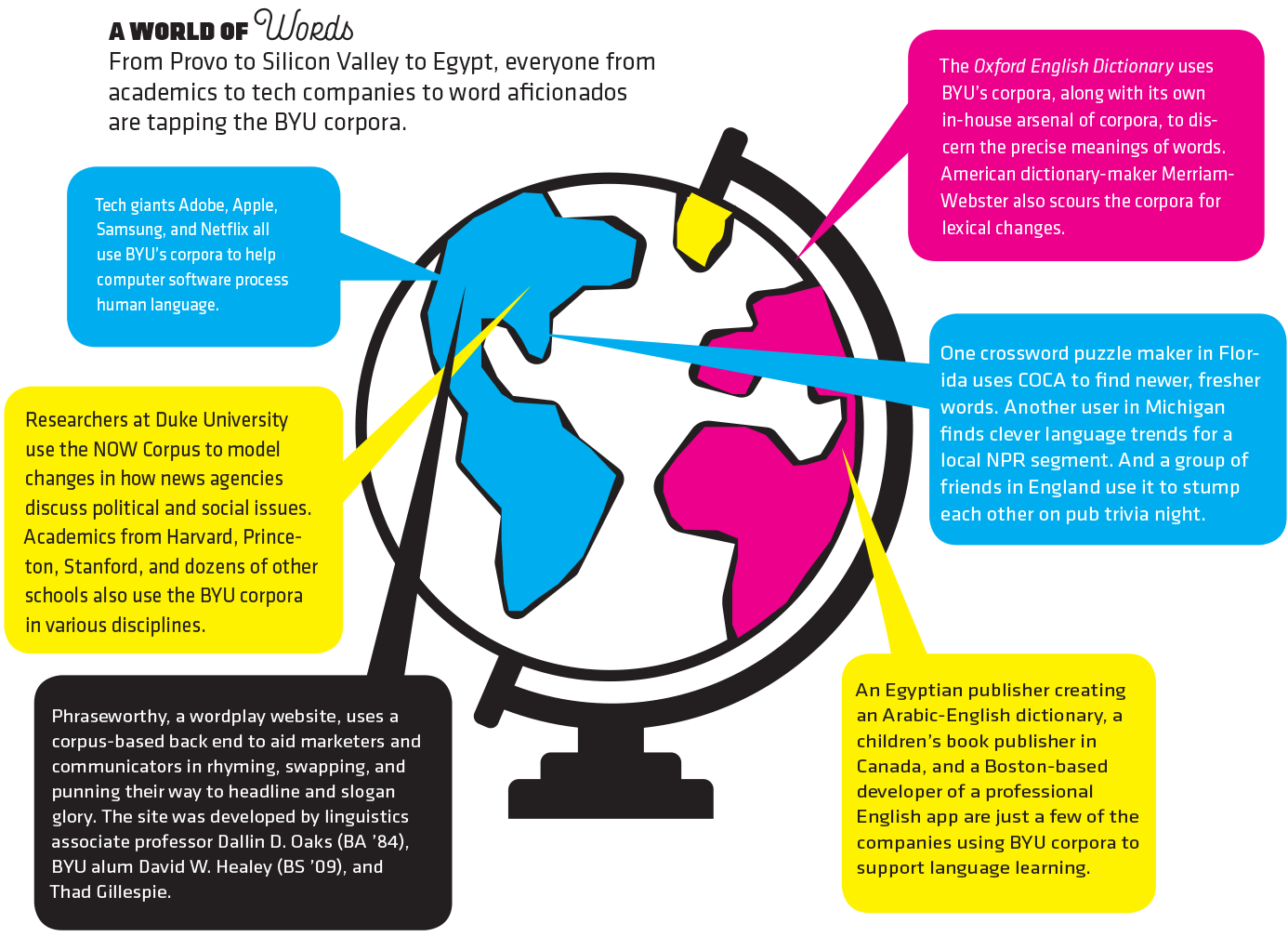

Every month more than 100,000 users—from Turkey, Korea, Sweden, Russia, Sri Lanka, Iran, and more than 100 other countries—come to the BYU corpora. Some are expected—like the editors of Merriam-Webster’s dictionaries; others are anything but—like a man in England looking for trivia questions (“He was using the BYU corpora for his pub game,” says Davies).

University of Helsinki historian Jani Marjanen uses the corpora to examine cultural change via language. He studies the emergence of “-ism” words: “Now with Trump and Putin, we immediately have Trumpism and Putinism as political catchwords,” he notes.

Chief Justice John Roberts cited Davies’s COCA in a 2011 Supreme Court opinion, just one example of lawyers, judges, and academics using the corpora to track the evolution of word meanings in the legal realm (see “Judging Language,” below).

And developers all over have mined the BYU corpora for hundreds of language-learning apps—like the vocabulary-flashcard app created by a Korean developer using COCA data (see “Speak Like a Native” below).

The wide interest has been a surprise for Davies, who originally thought only linguists would take interest. “In academia we publish these articles that 15 people read and 3 people care about,” he jokes. “I long ago stopped trying to predict who would be using the corpora and for what.”

And Davies never knows what type of corpus he’ll create next. Some ideas have woken him in the middle of the night; others come through collaboration with cross-disciplinary researchers. “I keep telling my wife, . . . ‘This is the last corpus. Really, I’m done now,’” he says. “She just rolls her eyes. . . . It’s like an addiction.”

Judging Language

When James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and the other Founders crafted the U.S. Constitution, they created a 4,379-word document with which lawyers, judges, and politicians have wrestled ever since. A lot has changed since America’s founding—including the meaning of many of the Constitution’s words.

So how do 21st-century judges interpret 18th-century texts? Most use “dictionaries and etymologies supplemented by intuition,” says Law School dean D. Gordon Smith (BS ’86). But he and others at the J. Reuben Clark Law School see a better way to reduce legal ambiguities by using corpus linguistics—and they are leading the way in the emerging field.

“It’s just starting to take off,” says Smith. “It’s fun to watch the launch.”

With Davies, BYU law professors are creating a suite of corpora specifically geared toward legal language. There is a newly created corpus of Supreme Court opinions, and a corpus of texts from America’s founding period is in the works. Both will lend clarity to legal word usage. “Corpus [data] can’t answer every question,” says Smith, “but it can shed light for a field that is so dependent on word meaning.”

Utah Supreme Court justice Thomas R. Lee (BA ’88) teaches a class on corpus linguistics at the Law School with Smith and BYU alum Stephen C. Mouritsen (BA ’02, MA ’07, JD ’10). He believes that corpus linguistics can make the interpretation of law more trustworthy and consistent and act as a check on judges so that “it’s really interpretation and not just a smokescreen for imposing [judges’] own preferences. If it isn’t transparent and predictable, fortunes and freedoms and lives can be jeopardized.”

“BYU is really at the center of this universe of law and corpus linguistics,” he adds.

In February the Law School hosted the first-ever corpus linguistics and law conference held in the United States. Among the participants was Lawrence Solum, a law professor at Georgetown University. “In my opinion, corpus linguistics will revolutionize statutory and constitutional interpretation,” he says. “[It] has already been used by the Supreme Courts of both Michigan and Utah—and this is just the beginning.”

Speak Like a Native

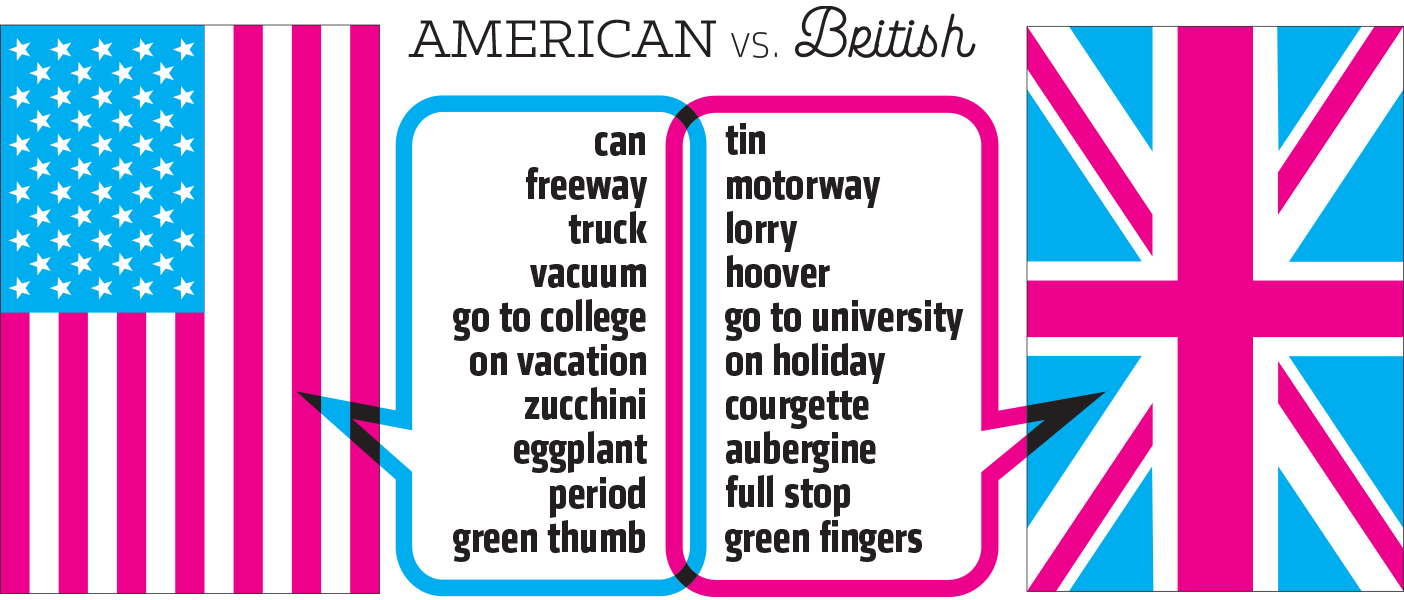

How would a native English speaker say it? That question drives hundreds of thousands of users from around the globe to the BYU corpora every year. While English learners have had bilingual dictionaries at their disposal for hundreds of years, corpora substantiate grammar-book rules and provide endless examples of elucidating subtle variations in meaning.

“COCA [the Corpus of Contemporary American English] is being used daily by people throughout the world to learn English, which can improve their lives,” says Davies, who estimates that some 70 percent of all BYU corpora users are there to learn or teach English.

Professors at Uludag University developed English-teaching materials for the Turkish government. The Austrian Ministry of Education created reading and listening tasks for the national English exam. And the U.S. Department of Defense’s Foreign Language Institute teaches international military students.

Jessica Williams, linguistics professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, says the BYU corpora have been “a revelation” for her TESOL master’s students. “I believe no teacher-preparation course would be complete if it does not acquaint students with corpus resources,” she says. “COCA has been invaluable. My students joke all the time, ‘Let’s check COCA!’”

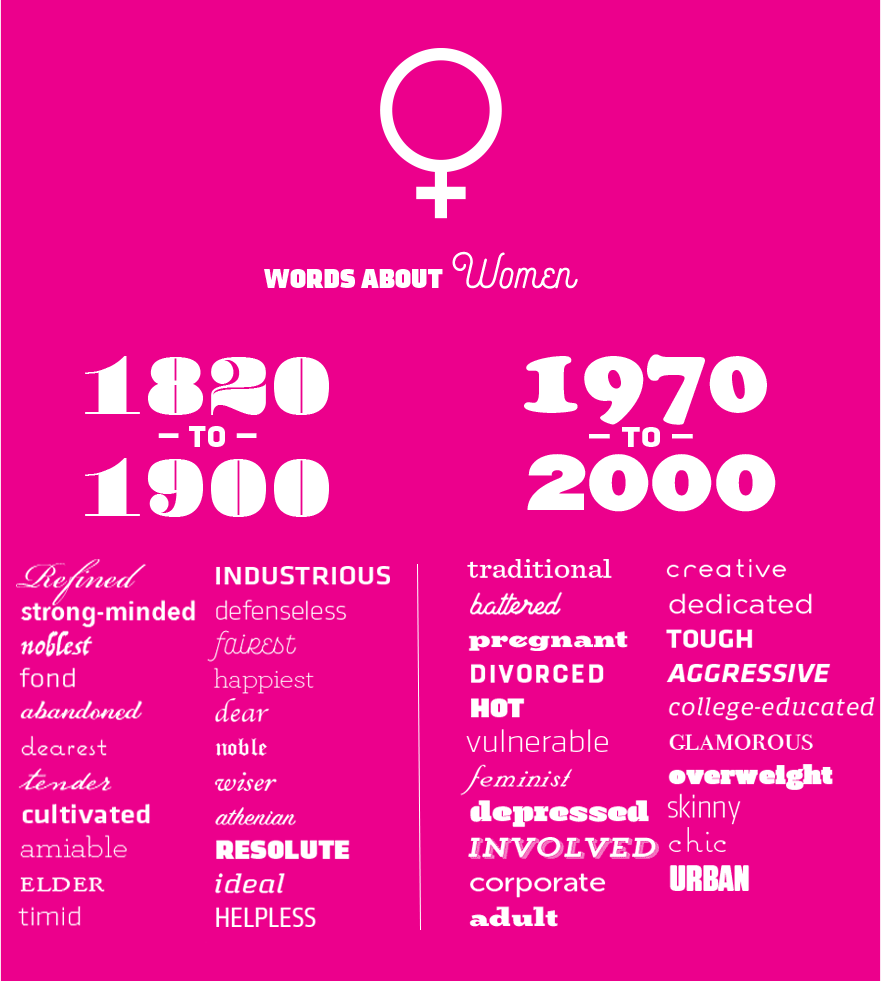

Words About Women

Corpora can show the “friends words keep” by identifying their most common neighboring words (known by linguists as collocates). For instance, using Davies’s Corpus of Historical American English to compare some of the most common adjectives that appear near the word women in two different time periods—1810–99 and 1970–2009—reveals major shifts in attitudes about women and their role in society.

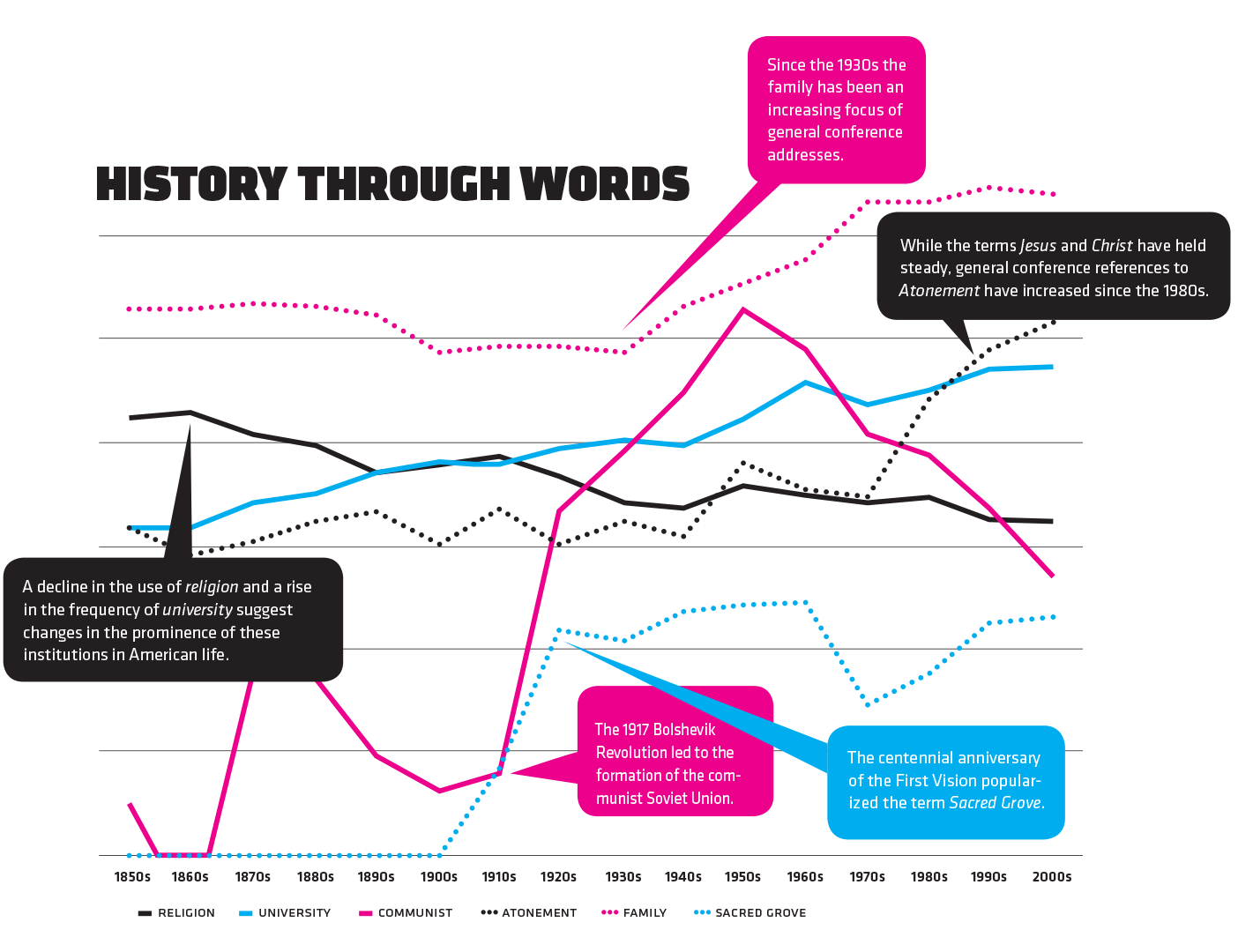

History Through Words

Corpora can be used to analyze historical trends and events. This chart tracks the relative frequency of usage for six words over the last 150 years using the Corpus of Historical American English (solid lines) and the LDS General Conference Corpus (dotted lines).

As seen in the chart, the family has been an increasing focus of general conference addresses, references to Atonement have spiked, and the centennial anniversary of the First Vision popularized the term Sacred Grove. Meanwhile, in general American usage, we’ve seen a decline in the use of the word religion and a rise in the frequency of the word university, suggesting changes in the prominence of these institutions in American life.

WEB: Try out the BYU corpora at corpus.byu.edu.

FEEDBACK: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.