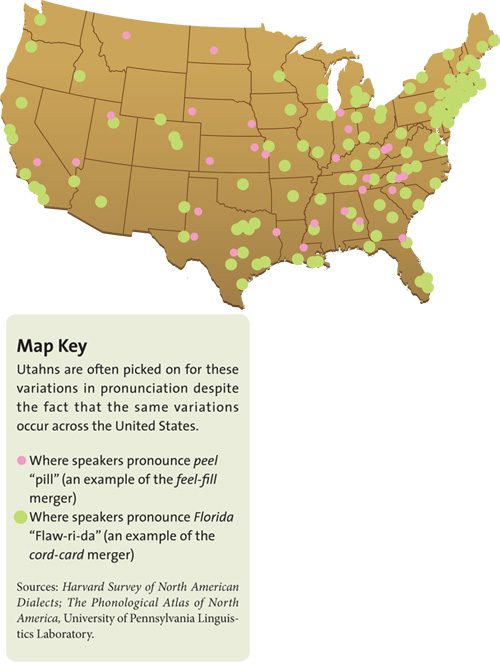

BYU research shows that Utahns are not alone.

John Denver sang, “rocky mou’un high”; Diana Ross and the Temptations sang, “ain’t no mou’un high enough.” All across the country, Americans drop t’s to the back of their throats (called a glottal stop)—but Utahns, with their “Wasatch Mou’uns,” seem to get the most grief for it.

BYU linguistics professor David S. Eddington (BA ’86) recently published studies on Utah’s glottal stop in words like mountain (mou’un) and kitten (ki’un) in American Speech. “It’s not the t-dropping that’s interesting,” Eddington says of the Utah dialect. “What’s interesting is what happens after that sound.” Utahns release the vowel after the t through their mouths instead of their noses. But they’re not alone. Linguists have noted the same oral vowel release in California, New Jersey, and elsewhere.

Why, then, does Utah get so much attention for it? BYU linguistics assistant professor Wendy Baker Smemoe (BA ’91) says many Americans may look down on Utah English because they perceive Utah as backward and rural. “Utah seems really rural compared to places like Southern California,” she says, and “Americans always rank rural [language] varieties lower than urban varieties.”

Common Utah vowel mergers like fail–fell (“Did you fell your test?”), cord–card (“Flarida Arange Bowl”), and feel–fill (“It’s the rill dill.”) also show up in the Northeast and South. “New Yorkers right now say ‘harrible,’ which is a cord-card merger,” says Smemoe. “But because we have positive feelings about the Northeast, we don’t think it’s weird.” Eddington adds, “I’ve tried to look for a characteristic that’s just in Utah, and I haven’t found one yet.”

Just where did the so-called “Utah-isms” originate? Some, like pro-predicate do (“You ski much?” “I used to do.”), came from English immigrants. Former BYU professor David F. Bowie was one of the first to research the Utah dialect in great depth and says Utah’s mix of northeastern vocabulary and southern accent are also remnants of the LDS migration. “The way you speak reflects a connection with where you’re from and how you grew up,” says Bowie. “People should be unafraid to talk however they want to.”

Not Just American Fark

Is Utah English really all that different? BYU linguistics professors David S. Eddington (BA ’86) and Wendy Baker Smemoe (BA ’91) offer their take on Utah dialect stereotypes.

Warsh for Wash: typical of rural American English; found in Utah but not prevalent.

Crick for Creek: ditto.

Skull for School: typical of younger Utah speakers, but originated in Southern California. Thank you, surfers.

Melk for Milk: typical of Utah dialect; it’s uncommon in Standard American English to relax a vowel before l. Gotcha, Utahns.

Mondee for Monday: feature of older Utahns’ speech, but also typical of southern American English.

Hembook for Hymnbook: similar to the pin-pen merger in southern American English.