The BYU visit of two Arab dignitaries transcends political, linguistic, and cultural borders.

Sand, oil, and water define the Arabian Peninsula. Sand and oil by their abundant presence. Water by its utter absence.

In the peninsula’s Rub‘ al-Khali—the Empty Quarter—shifting mountains of sand cover an area about the size of Utah, Nevada, and southern Idaho. Temperatures reach above 120 degrees Fahrenheit, undulating dunes rise and fall hundreds of feet, and portions of the desert can go untouched by rain for years at a time. Thousands of feet beneath the forbidding, gritty landscape, extensive reservoirs of oil pump incredible amounts of money into the region’s economy.

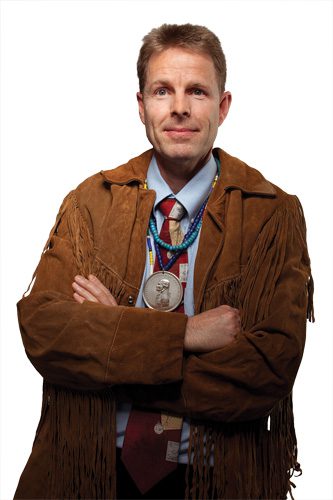

On a day when his U.N. colleagues in New York are occupied by Iran’s nuclear program, al-Hinai reviews notes prior to giving a joint lecture with his wife at BYU. The first ambassador couple to visit campus, the Omanis shared insight into their culture, their country, and global politics, as have some 100 other ambassadors in the last decade.

Halfway around the world in the United States, drivers standing at gas pumps quickly associate their pinched pocketbooks with news reports of lavish Arabian building projects. Elected officials bemoan U.S. dependence on foreign oil, and analysts discuss the effect of world politics on the price of a gallon of gas.

In the larger realm of international relations, however, economic strain is just one of many factors—including cultural, religious, and political differences—that fuel tension between the Middle East and the West. In Western stereotypes Middle Eastern societies seem as harsh and alien as the vast Rub‘ al-Khali, and from a common Arabian perspective, Western morality is as inconsistent as windblown dunes. At times the prospect of forging friendly relations seems as likely as mixing oil and water.

Against such a backdrop of international affairs, diplomatic envoys earn their keep, building relationships across contrasting cultures and countries.

On a bright fall morning—with gas prices and Middle Eastern politics appearing regularly in U.S. headlines—two Arabian ambassadors emerged from the back seat of a black Suburban at the base of reddening Wasatch Mountains. Smartly dressed in business suits, the envoys represented the Islamic country of Oman—one as the ambassador to the United States, the other as the representative to the United Nations.

The first of several ambassadors who would visit BYU campus during the semester, they had come to Utah—on the fringes of the Great Basin Desert—at the university’s invitation. The Omanis were scheduled to spend their first day at BYU, speaking to students, lunching with professors, and touring campus. The next day would be spent in Salt Lake City, where, among other activities, they would meet the governor of Utah and the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Omanis’ agenda was similar to that experienced by about 100 other ambassadors hosted by BYU since 1997.

The ambassadorial visits program, directed by associate international vice president Erlend D. Peterson (BS ’67), builds international connections for the university and for its students. Some ambassadors come from familiar places with natural connections, like Europe, while others, like the ambassadors from Oman, represent parts of the world unknown to most students—nations and cultures with which students might more easily list differences than similarities.

As the sunlight grew steadily across campus, casting long tree shadows on the lawn and patio, university officials welcomed their Middle Eastern guests outside the administration building. It was the second day of fall semester, and the hosts had lingering anxiety about the visit. It was difficult to predict whether students—still figuring out schedules and greeting friends after a long summer’s absence—would attend or even be aware of a lecture by a pair of ambassadors from the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula.

Opening a Dialogue

Just five days before Fuad al-Hinai left New York to visit BYU, the United Nations deadline for Iran to stop enriching uranium had passed unheeded. While U.S. president George W. Bush called for consequences to be imposed, Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad insisted he would not be intimidated. Al-Hinai’s concern for the Iran situation went beyond his role as a member of the U.N. general assembly: Oman’s northern tip lies within 40 miles of Iran’s southern coast, just across the Persian Gulf’s Strait of Hormuz.

Though al-Hinai’s wife, Hunaina al-Mughairy, shared his concern for Iran, she faced other pressing issues. As the Omani ambassador to the United States, al-Mughairy had been focusing her efforts on brokering a free-trade agreement between the two countries. Congress had passed the treaty over the summer, and in September it was slated for final U.S. approval.

Despite these pressures, the couple had left their respective offices in New York and Washington, D.C., to come to Utah. Though neither ambassador had visited the state before, BYU was not entirely unfamiliar to them. A few years earlier al-Hinai had received a copy of a book published by BYU—a side-by-side English and Arabic publication of a work by an ancient Islamic philosopher. And in 2005 al-Mughairy had attended the Washington, D.C., premiere of a BYU documentary about the ancient incense trail, a trade route that for more than 1,000 years carried frankincense from southern Oman up the Arabian Peninsula to Mediterranean countries.

At the premiere, al-Mughairy met S. Kent Brown, the BYU professor of ancient scripture who had produced the film. A year later, at BYU, the reserved, gray-haired professor was serving as the ambassadors’ host, accompanying them into the administration building to meet BYU president Cecil O. Samuelson and officially begin their visit.

At the door to his third-floor office, President Samuelson warmly greeted the Omanis and directed them to a pair of navy blue leather armchairs near the large north-facing windows. The president had welcomed many ambassadors to his office, but these two composed the first husband-wife ambassador team to come to BYU. After exchanging pleasantries, President Samuelson explained why he had invited the couple to campus: “One of the remarkable things, I think, about Brigham Young University is that really from the beginning it’s had a very strong international orientation, and because of our strong religious beliefs about us all being brothers and sisters, it is important that we understand as much as we can about the world.”

The philosophy behind such outreach resonated with al-Hinai. “Our head of state has always believed in dialogue,” al-Hinai told President Samuelson, referring to Oman’s sultan, who has reigned since 1970. Although Oman’s seal displays two crossed swords and a sharply curved khanjar dagger, the weapons on the emblem are sheathed. The symbol is fitting; the Islamic nation is not prone to solve problems with military force. Over the years, the Kansas-sized nation has been somewhat independent from other Islamic states, fostering diplomatic ties with countries its peers have spurned. “We live far apart,” al-Hinai said, “but we come together, we talk to each other. We may have different beliefs, but it’s extremely important that we always have this connection.”

The philosophy behind such outreach resonated with al-Hinai. “Our head of state has always believed in dialogue,” al-Hinai told President Samuelson, referring to Oman’s sultan, who has reigned since 1970. Although Oman’s seal displays two crossed swords and a sharply curved khanjar dagger, the weapons on the emblem are sheathed. The symbol is fitting; the Islamic nation is not prone to solve problems with military force. Over the years, the Kansas-sized nation has been somewhat independent from other Islamic states, fostering diplomatic ties with countries its peers have spurned. “We live far apart,” al-Hinai said, “but we come together, we talk to each other. We may have different beliefs, but it’s extremely important that we always have this connection.”

The Muslim ambassadors and Mormon academics discussed relationships between BYU and the Arab world, and the discussion eventually turned to challenges facing Oman. Al-Hinai mentioned the issue of finding opportunities for the country’s youth—43 percent of the population is under age 15, compared to 20 percent in the United States—and al-Mughairy discussed the need to diversify Oman’s economy away from its dependence on oil. The free-trade agreement with the United States may help with both issues, bringing jobs and industries into the country.

BYU may also find a way to contribute. Oman is seeking to expand tourism as an area of economic growth, and Brown had mentioned earlier that Omani officials have contacted him about using portions of the incense trail documentary at tourist sites.

President Samuelson and the Omanis discussed other potential ties between BYU and Oman, and the ambassadors warmed to the promise of further connections. “Next time I go to Oman and I see the minister of higher education,” said al-Hinai near the end of his Utah visit, “I will certainly pose a question to her: Why isn’t she sending students to BYU? Now it is time that there is a tie between BYU and our ministry of education in Oman.”

Al-Mughairy applauds a children’s choir at a dinner with leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ in Salt Lake City. Ambassadors, like the Omanis and Sudjadnan Parnohadiningrat, from Indonesia, who visit Utah at BYU’s invitation are treated to meetings with Church, political, and business leaders as well as with students and professors.

Intercultural Ties

With a soft whine, the long white tour cart rolled quietly southward across the wide sidewalks toward the next stop on the Omanis’ itinerary—the newly renamed Neal A. Maxwell Institute. As the cart moved along, students stepped politely out of the way. The modesty and clean appearance of the students impressed the Muslim visitors, who have two grown children of their own. The Islamic culture adheres to similarly high standards of behavior, and Muslims frequently find themselves at odds with typical Western morality, especially on college campuses. At BYU, however, they find no such conflict.

“If I were to have a son or a daughter who was in high school, I would definitely ask him or her to apply to go to BYU,” al-Hinai remarked later, noting BYU’s academic quality and particularly mentioning the wholesome environment. “Most important are the values that BYU maintains, which are so similar to ours.”

The covered cart parked near the Maxwell Institute, where the ambassadors would discuss BYU’s effort to share medieval Middle Eastern texts with the modern world. Typically neglected by Western academics—largely because of the language barrier—medieval Arab and Muslim scholars represented what was arguably the most advanced culture in the world for many centuries. Disturbed by this disregard for medieval Arabic studies, especially given today’s growing need to understand the Islamic world, BYU scholars began publishing translations of Arabic works in the 1990s.

Inside a former private home that has been transformed into office space, Maxwell Institute executive director Andrew C. Skinner and editor D. Morgan Davis Jr. (BA ’95) welcomed the Omani ambassadors to Skinner’s modest office. On an oval wood table sat the words of several Middle Eastern scholars, bound in hard covers of green, blue, red, and black. The fruit of a decade of toil, some of these works had never before been published in English, though their authors are well known in the Arab world.

Inside a former private home that has been transformed into office space, Maxwell Institute executive director Andrew C. Skinner and editor D. Morgan Davis Jr. (BA ’95) welcomed the Omani ambassadors to Skinner’s modest office. On an oval wood table sat the words of several Middle Eastern scholars, bound in hard covers of green, blue, red, and black. The fruit of a decade of toil, some of these works had never before been published in English, though their authors are well known in the Arab world.

Al-Mughairy and al-Hinai thumbed through the works on the table. A few years before this visit, they had received a copy of the first volume, an 11th-century Islamic philosophical work by Abu Hamid al-Ghazali. Seated across the table from the ambassadors, Davis explained the early years of the project and his experience with it. “I began as a part-time research assistant, just typing the Arabic. I couldn’t even really understand the things I was typing,” he said. Davis, who recently completed a PhD, is one of many former students who have learned about Arabic scholars by assisting in the publication of the series. For Davis, his undergraduate exposure to the project awakened an interest in Arabic and Islamic studies. “I got to read al-Ghazali in translation and realized this is a really interesting character. I identify with a lot of his personal quest for truth. There was a connection there across many centuries between me and a philosopher that I’d never heard of before.”

As the visit concluded, Skinner made arrangements to send a set of the volumes to the ambassadors, who offered their encouragement for the project.

Skinner, along with translation series director Daniel C. Peterson (BA ’77), has presented the series to a number of Islamic scholars and world leaders. The reactions of admiration and gratitude for the respect shown their culture are consistent, he said, and visits from Arabic dignitaries like the Omanis help the BYU scholars to better understand the value of their academic work. “It certainly builds greater bridges of understanding between two cultures that are not all that dissimilar,” he remarked after the meeting.

Diplomatic Grilling Grounds

At 2:30 the wood-paneled Kennedy Center lecture room was peppered with students—some already in their seats, others browsing the fruit trays and assorted cookies in the back.

Stepping to the podium, Cory Leonard (BA ’94), assistant director of the Kennedy Center, welcomed the diplomats to the Model United Nations class and told his students, “Today we will learn some things we could never learn in class on our own. It’s a great privilege to hear from such distinguished people.” He then gave the floor to the ambassadors.

Wearing a hazelnut suit and gold jewelry accents, al-Mughairy spoke briefly, a silhouette of the world gracing the wall behind her, a crowd of BYU students before her. Then al-Hinai stood. “I am delighted to be here,” he began. “I would like to first congratulate all of you on having been accepted to BYU. It’s a great institution and has a wonderful name throughout the world.”

Earlier in the day, al-Mughairy had also praised the university as she stood at the same podium and addressed another group of students on the history and culture of Oman. That previous setting had been the Kennedy Center’s first Global Awareness Lecture of the semester, and despite occurring on the second day of classes, the event drew a large crowd, filling the room with students and faculty from diverse disciplines and backgrounds. The Model U.N. lecture, in contrast, provided an intimate occasion in which fewer than three dozen students interested in international politics could interact with the ambassadors.

The subject of al-Hinai’s remarks—a typical workday at the United Nations—was appropriate for the aspiring young diplomats. Before getting to the office, he told them, he picks up a newspaper to brush up on last night’s news. As soon as he arrives, he checks the U.N. daily events journal. Then the day is filled with seminars, lobbying, and negotiations.

Al-Hinai, wearing a gray suit with a blue shirt and tie, also straightened out a misconception: “Some people say, ‘Oh, diplomats—they party all the time.’” He pressed through the laughter, “Yes, we do. But at the same time we work. Those lunches are not free.” Despite their festive appearance, diplomatic receptions are really grilling grounds. “You have to give your opinion on any subject that your host brings up.”

After al-Hinai’s presentation, a lively question-and-answer session ensued, and the students showed themselves to be both well informed and bold. International relations and comparative literature major Zachary S. Davis (’09) posed a question about human trafficking in Oman. The topic was a sensitive one. In the U.S. State Department’s 2006 report on human trafficking, released over the summer, Oman had been criticized for not doing enough to combat the problem. The issue had also become a point of significant discussion during congressional debates about the Oman Free Trade Agreement, which al-Mughairy had been working on since before she became the ambassador to the United States in 2005.

On a cool October day, Nigeria’s ambassador to the United States, George A. Obiozor, enjoys BYU’s Homecoming victory over UNLV. Through their visits, ambassadors build personal and official ties with the university and its people.

Al-Hinai gave the first response to the question, noting that labor tribunals have been set in place to protect Oman’s workers. Al-Mughairy quickly stepped to the podium to tackle the issue as well. She asserted that Oman does not support human trafficking and explained that a 24-hour hotline provides a channel through which laborers can report mistreatment. Her final statement was firm. “We’ve always disputed this with the State Department: that we do not have human trafficking.”

After half a dozen other queries, a young woman stood and asked, “On a personal note, what did both of you study and what made you decide you wanted to join the civil services?” Al-Hinai responded that his first degree was in English language teaching, while his wife had studied business. Then he shared a small anecdote. “When we were in New York,” he said, referring to his first U.N. post, in the 1970s, “she did a master’s at NYU while I stayed home and looked after the baby when she went to class.” This scenario—reminiscent of many BYU student couple arrangements—elicited warm laughter from the students.

After the lecture, Davis reflected on the ambassadors’ response to his question about human trafficking. “I’m sure the U.S. State Department has good reasons for criticizing Oman for the trafficking,” Davis said, “but it’s a relatively progressive country, and at least they’re trying to address it.” In addition to getting a personal answer to his political question, Davis said the lecture had enhanced his overall perception of international relations. “This puts a face and a person to the idea of diplomacy,” he said. “You realize that these huge bodies like the U.N. are actually composed of normal people who you can talk to, who have families.”

Reem N. al-Sabah (PhD ’06), a young woman from Kuwait who recently earned her PhD at BYU, had a different reason for coming. She said the concept of a female ambassador from her part of the world sparked her interest. “It’s nice to see someone who is female and who holds a high position,” said al-Sabah.

The issue of gender equality in Arabia was also important to al-Mughairy, who is the first female ambassador to represent an Arabian country to the United States. “The West always perceives women in the Middle East as suppressed,” she later reflected. “By me talking to [these students], it has shown them that that is not the case. Here is an Arab woman who is able to speak their language and who is able to show that Omani women are not as suppressed as what is being portrayed. I think these students will have a different image now about women in the Middle East.”

A Gift of Peace

Through floor-to-ceiling windows, the Ambassador Room, on the Joseph Smith Memorial Building’s top floor, offers views down into Temple Square and across the north end of Salt Lake Valley. As the hosts for the evening, Elder Robert C. Oaks, of the Seventy, and his wife, Gloria, waited in the room for the ambassadors. The sun still hung high behind hazy clouds in the western sky when al-Mughairy and al-Hinai arrived, ushered into the room by emeritus General Authority Elder Ben B. Banks, who, with his wife, Susan, would join the dinner as the directors of Church hosting. Immediately attracted to the neo-gothic temple spires rising into view outside the western windows, the diplomats moved closer to admire the building. A soft blue light filtered through the windows and illuminated their faces as they asked questions about the temple and listened carefully to Elder Oaks’ responses.

Beyond the similarities in behavioral standards, the religions of Islam and the Church of Jesus Christ share a deep faith in God and personal religious devotion expressed through prayer and fasting. In Oman, the dominant Islamic sect is Ibadi, a moderate version of the faith that has avoided the association with terrorism that has plagued more extreme Islamic sects. But to many Westerners all Islam may seem enigmatic and violent. Earlier in the day, BYU political science professor Donna Lee Bowen had discussed how personal interactions, like the visit of the Omani ambassadors, can break down such barriers of misunderstanding. “From my point of view, the more people from the Middle East my students can talk to and spend time with, the better they’re going to understand the Middle East,” remarked Bowen, after sitting next to al-Mughairy at a luncheon. “But they also gain a very different perspective of what the region is all about and what the people are about. It’s so easy when we don’t know someone to demonize them. And it’s so difficult when we do know someone to demonize them.”

As the dinner of herb-crusted salmon and fresh fruit concluded in the Ambassador Room, some 80 children arrayed in colorful international costumes began to file in, circling the table and crowding against the walls. A young girl in traditional Arabic dress stepped forward and greeted al-Mughairy and al-Hinai in Arabic, and the choir began to sing, their clear youthful voices surrounding the dinner party and filling the room. The delighted Omani couple listened through several songs, including one called, “Salma Ya Salaama.” Sung by the children in Arabic, the song refers to a woman by the name of Salma. Turning to see the children around her, al-Mughairy was visibly touched.

“Salma also happens to be the name of Hunaina’s mother,” al-Hinai said later, explaining his wife’s reaction. The song, he said, mentions going and coming in peace.

“In peace,” al-Mughairy interjected, moved again by the memory of the song. “It’s about peace.”

The Arabic word for peace is salaam, al-Hinai revealed. Thus the song employs wordplay, for Salma is a derivative of salaam.

Backed by the tall windows and emerald green curtains of the Ambassador Room, scores of Latter-day Saint children gave voice to Arabic expressions of peace—their gift to an Islamic couple from Oman. “Salma ya salaama / Rohna wa geina bel-salaama,” they sang. Peace, O Salma, may we go and come in peace.

View online video recordings of past Kennedy Center lectures given by international visitors at https://kennedy.byu.edu/lectures/.

FEEDBACK: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

In the BYU Visitors Center lobby—formerly the living room of the president’s home—a handful of guests sit on elegant sofas and skim the pamphlets and magazines scattered across the coffee table. After a few moments, a student tour guide greets the group and invites them into an adjacent room to watch the 10-minute video Brigham Young University: A Foundation of Faith in one of 10 different languages. After this introduction to the university, the guests and guide climb aboard a tour cart to explore campus.

Since Hosting Services, later renamed Public Affairs and Guest Relations, was established in 1976, the number of visitors who request a tour each year has grown from about 5,000 to more than 17,000, outgrowing the historic house as a headquarters. In fall 2007 the Gordon B. Hinckley Alumni and Visitors Center will provide a new and improved home for this increasingly popular campus service.

The guests spend the next 50 minutes learning about campus and its history as the guide drives them across campus sidewalks. This tour is given to all who come to the Visitors Center, ambassadors and prospective students alike.

For prospective students, BYU’s Admissions Services provides additional experiences—the biggest of which is Y Weekend. Each year BYU brings nearly 600 top high-school scholars to campus for the weekend, giving them a taste of the BYU experience. Although about half of Y Weekend attendees arrive without particular plans to attend BYU, by the end of the experience some 80 percent say that BYU has become their top choice of schools, according to Troy A. Selk (BS ’00), an assistant director of admissions services whose office is in the Visitors Center.

Students are not the only ones who come away from their visit with new perspective. Ronald J. Clark (BA ’72), director of Public Affairs and Guest Relations, says he has seen numerous ambassadors and other dignitaries have a similar experience. “They leave changed,” he says. “They can’t help but feel the spirit that is here.”

While the Visitors Center is preparing to retire from its hosting duties, the new Gordon B. Hinckley Building is gearing up to serve university guests and alumni. Building features will include meeting rooms; gathering areas; a small library; an exhibit to teach visitors about the university, its history, and the value of a gospel-centered education; and a small theater that will show guests a movie about BYU’s history and purpose.

“Pretty soon we’ll have a new building where we can tell the BYU story,” says Clark. “We’ll be very happy to be in a building that has our beloved prophet’s name.”

—Lisa Dickson Washburn (BA ’07)

On Oct. 10, 2006, a Muslim and a Mormon stood at the same podium to call for greater understanding between the worlds of Islam and the West. Alwi Shihab, Indonesia’s presidential advisor and special envoy to the Middle East, delivered a forum address in BYU’s Marriott Center, following introductory remarks by his longtime friend President Boyd K. Packer, Acting President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Below are excerpts from their addresses.

President Boyd K. Packer:

Knit together by world history and by Old Testament history and doctrine, the Church and the Islamic world can see each other as People of the Book, indeed Family of the Book.

Church members and Muslims share similar high standards of decency, temperance, and morality. We have so much in common. As societal morality and behavior decline in an increasingly permissive world, the Church and many within Islam increasingly share natural affinities.

It is important that we in the West understand there is a battle for the heart, soul, and direction of Islam and that not all Islam espouses violent jihad, as some Western media portray.

It is as well important that friends in the Islamic world understand there is a battle for the heart, soul, and direction of the Western world and that not all the West is morally decadent, as some Islamic media portray.

Alwi Shihab:

Jews, Christians, and Muslims share the belief in One God who created us all from a single soul and then scattered us like seeds into countless human beings. They share the same father, Adam, and mother, Eve. They share Noah’s ark for salvation and Abraham’s faith, they share respect for Moses. . . .

It is, therefore, important to remember the major elements the three Abrahamic religions have in common to enable each of the respective adherents to feel close affinity to one another. In fact, Islam describes Judaism and Christianity as People of the Book, indicating that all the three religions are of one and the same family.

Let me suggest, dear brothers and sisters, that religious tolerance is not enough. We have often seen—particularly after the tragic events of 9/11 and, most recently, the Danish cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad—that tolerance does not always lead to true social peace and harmony. To tolerate something is to learn to live with it, even when you think it is wrong and downright evil. Often tolerance is a tolerance of indifference, which is at best a grudging willingness to put up with something or someone you hate and wish would go away. We must go, I believe, beyond tolerance if we are to achieve harmony in our world. We must move the adherents of different faiths from a position of strife and tension to one of harmony and understanding by promoting a multifaith and pluralistic society. We must strive for acceptance of the other based on understanding and respect. Nor should we stop even at mere acceptance of the other; rather, we must accept the other as one of us in humanity and, above all, in dignity.