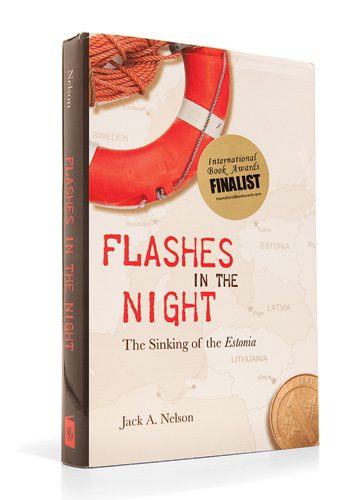

After a monstrous storm struck the ship Estonia on Sept. 28, 1994, the ferry capsized near midnight beneath frigid seas on its way from Estonia to Sweden. Of the 989 passengers and crew aboard, only 137 survived—making it Europe’s worst peacetime sea disaster of the 20th century.

Moved by the tragedy and determination shown on a stormy night on the Baltic Sea in 1994, Jack Nelson published Flashes in the Night: The Sinking of the Estonia, an account of Europe’s worst peacetime sea disaster of the 20th century.

Retired BYU communications professor Jack A. Nelson (BA ’54) recently published a gripping account of the tragedy titled Flashes in the Night: The Sinking of the Estonia, which has been awarded third place in the nonfiction category of the 2011 International Book Awards competition.

After Nelson, a former journalist, learned of the disaster and the heroism that occurred that terrible night, he felt there was a powerful story to be told. His cousin and former BYU roommate, William A. Sego (BS ’61), who had lived in Sweden and married a Swede, agreed and offered to finance the research.

“Bill paid our expenses so my wife and I could spend a month in Sweden and Estonia researching and interviewing people who had been involved in the catastrophe,” Nelson says. Among others, he spent an afternoon with Kent Harstedt, a survivor who is now a member of the Swedish Parliament. Harstedt became one of Nelson’s major characters.

On that fateful night in 1994 it took a mere 30 minutes for the listing ship to slide below the jagged Baltic Sea, but Harstedt was able to climb on deck and search for a lifeboat. There he met 18-year-old Sara Hedrenius, and they tried in vain to unfasten a boat that would not budge. He suggested they help one ano ther by staying together and added he would take Hedrenius to dinner in Stockholm if they survived.

ther by staying together and added he would take Hedrenius to dinner in Stockholm if they survived.

After leaping into the angry sea together, the duo saw an overturned lifeboat nearby and swam to it. They shared it with 22 people huddled together as near-freezing waves washed over the raft all night. Harstedt and Hedrenius sat in water to their waists and felt bodies bump around their legs as fellow passengers died. They stayed awake under impenetrable skies by hugging each other and telling jokes.

“They were rescued and had that date,” Nelson says. “It became famous all over the world.”

On the Sweden trip Nelson and his wife, Patrice Salisbury Nelson (BA ’68), traveled the same overnight journey from Estonia on the sister ship of the one that sank, prowling the bowels of the ship to get a feel of the survivors’ experience. Estonian Valeria Casper acted as translator for Nelson and helped him get interviews with various survivors and seamen.

Nelson was intrigued by the difference between those who endured the ordeal until rescue finally arrived and those who gave up—sometimes almost at the last minute. In Flashes in the Night he highlights the thin line that separates life from death.

“One factor is determination to make it, and the other is optimism without being overly optimistic,” Nelson says. “For example, with bitter-cold waves washing over them every few minutes, a voice survivors identified only as Mr. Positive kept reassuring everyone on the raft that they would be rescued any minute. He died after four hours. Many people on the Estonia just gave up. Some went into shock, sat down, and waited for their fate. But those who decided they would endure no matter how long it took were more successful at living.”

Nelson has published five novels. The most recent is To Die in Kanab: The Everett Ruess Affair, which, along with Flashes in the Night, is available on Amazon.com.