When history professor Christopher G. Hodson entered his Monday-evening class in fall 2021, what he saw wasn’t typical of a BYU classroom: windowless cinder-block walls, hand-me-down folding church tables, and 12 students wearing white jumpsuits—some sporting face tattoos.

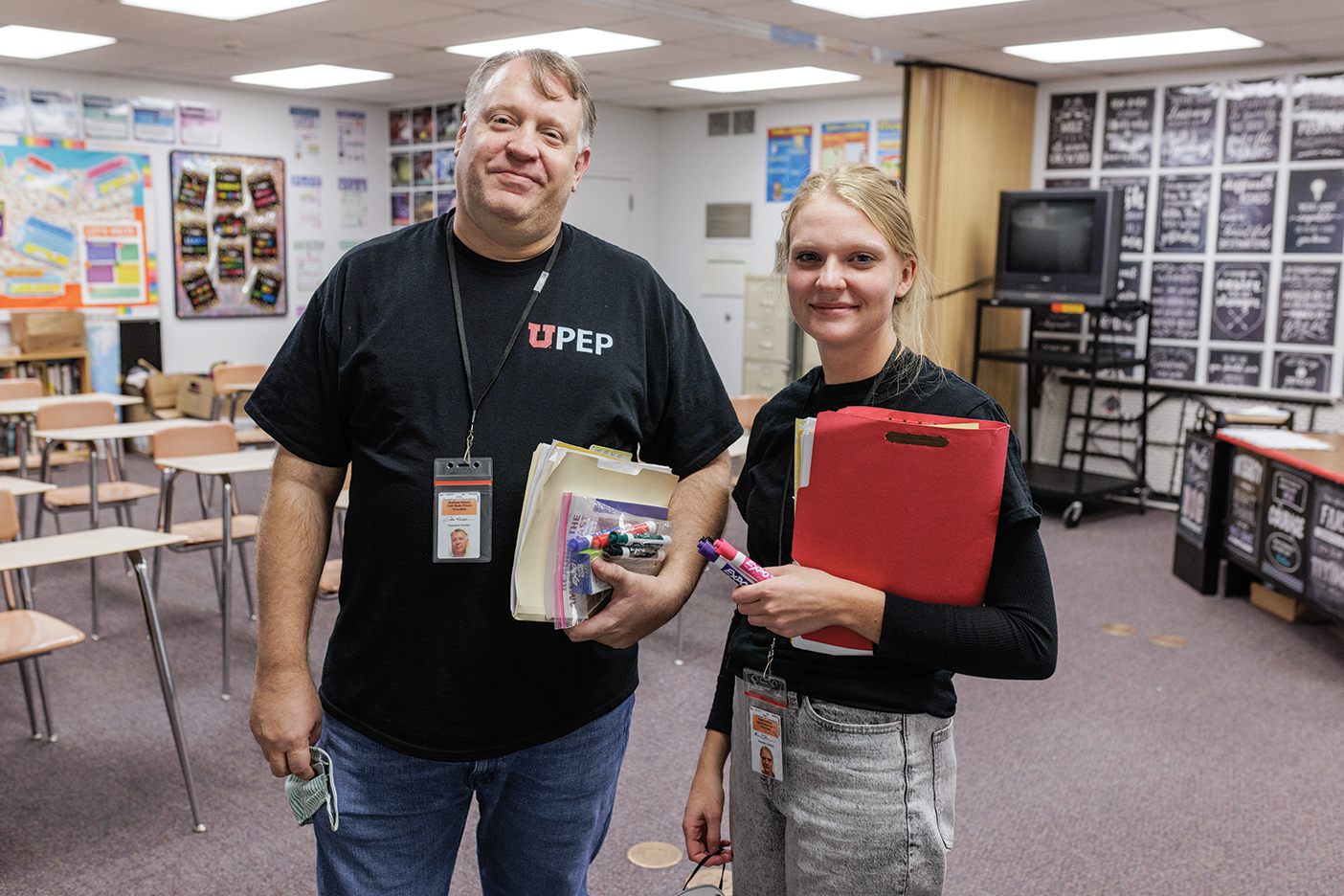

Hodson teaches a course on the French Revolution at the Utah State Prison in Draper, Utah. He and BYU colleague Matthew E. Mason, who teaches American history, are the first BYU volunteers for the University of Utah Prison Education Project (UPEP), which provides higher-education opportunities for incarcerated people.

Before fall 2021 college credit wasn’t offered for any UPEP courses. Now Mason and Hodson’s non-traditional students receive BYU Independent Study credit—and a glimmer of hope for a better future: “[They’re] realizing that . . . they’re worth so much more than [their mistakes],” says Kate A. Rolfson (’22), who conducted a weekly lab at the prison as Mason’s teaching assistant.

“The degree of difficulty that these students face is really, really high,” Hodson says. For example, the students are required to handwrite their papers. “The penmanship is unbelievable,” notes Hodson, describing the first set of essays he received.“ They actually made their own footnotes down at the bottom.”

Plus, “you’re at the mercy of so many different variables,” explains Hodson—including literal lockdowns to stop the spread of COVID-19, changes in students’ job schedules, and students’ being sent away to serve the federal portion of their sentence. “Every time you draw up a syllabus, you know it’s a tentative syllabus,” Mason laughs.

Even so, former inmate Silia Olive says education changed her life. Olive took six UPEP classes without receiving credit. Along the way, she says, she transformed from the “prison’s worst nightmare”—taking part in drama, drugs, and gangs—into a straight-A student. Now, Olive is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in business with two other previously incarcerated students. “I know that education saved [us] in there,” says Olive. “What happened to us . . . is not going to define who we are for the rest of our lives.”

And it’s life changing for the teachers too. “Getting people to interact with incarcerated folks, understand their set of experiences—I think that’s a huge win,” says Hodson. Mason sees this outreach as going “to what the Savior called ‘the least of these’—people who are completely marginalized in our society—and just interacting with them as students.”