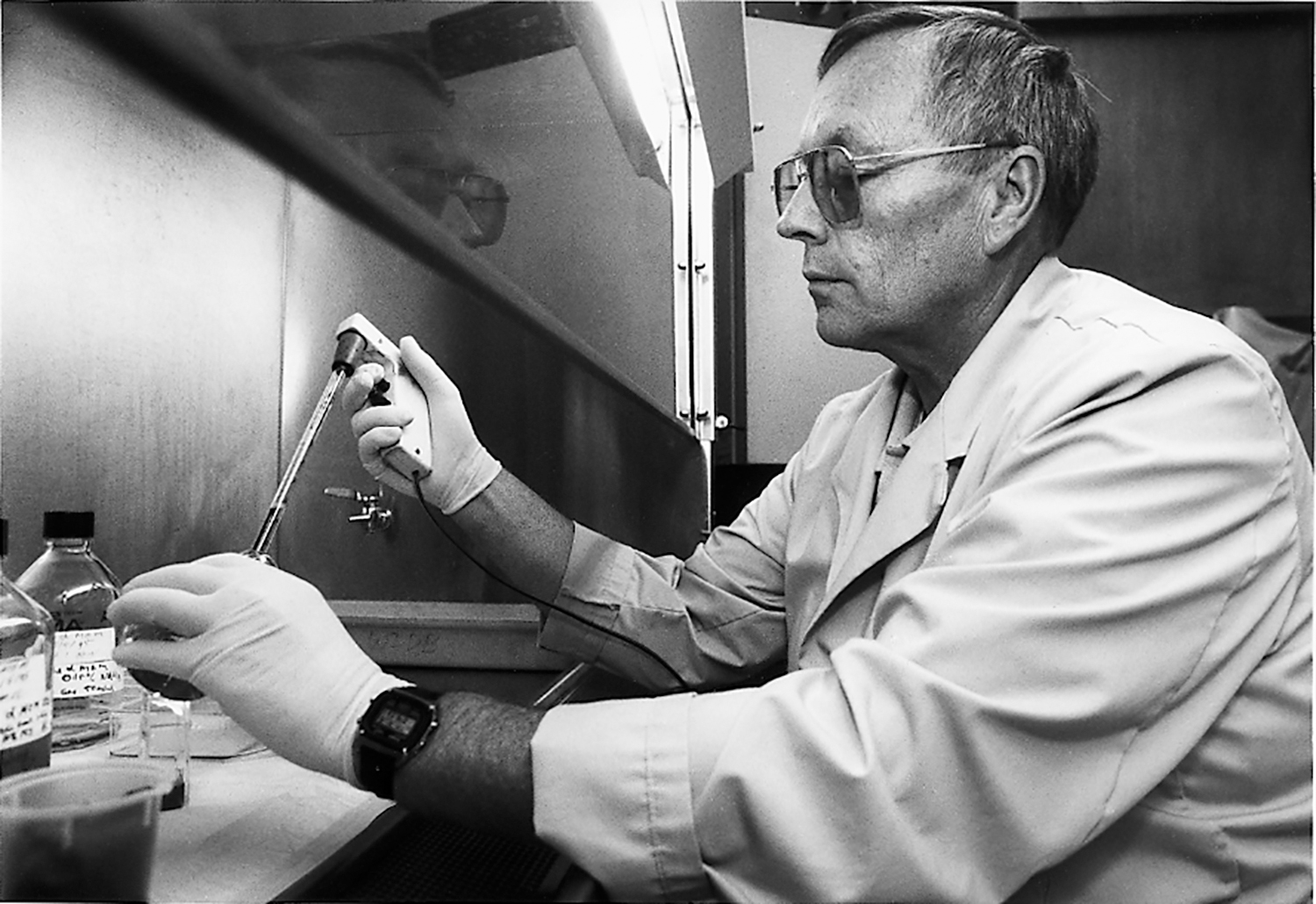

BYU professor Byron Murray says diseases move from animals to humans as man alters the ecology. Photo courtesy Stuart Johnson/ Deseret News.

As humans continue to explore new habitats, they will become more susceptible to foreign strains of bacteria and viruses carried by animals, plants, and insects, says a BYU professor.

Many deadly “emerging diseases”—including the Ebola virus, Hantavirus, E. coli bacteria, and HIV—can be traced to animal populations, says microbiology professor Byron Murray, who conducts research on anti-viral drugs. He says these mysterious diseases are likely to increase in number.

“We’re altering the ecosystem and the ecological niches so a lot of animals are living where they didn’t live before. And as we move into new areas, humans are coming across not only viruses but a variety of other infectious agents that can be devastating,” he says.

“And with world travel today, the spread of potentially deadly infectious diseases is of real concern.”

Ecological and environmental changes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), are key factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. But other factors, including international travel, human behavior, technology, microbial change, and a general breakdown of public health measures, also perpetuate the spread of disease.

“There are a lot of changes in the world, changes that are bringing humans into contact with these viruses. It is not just cutting down the forests and moving into new areas—all kinds of changes affect the viruses and how they’re spread,” says Murray.

The CDC has identified 30 emerging diseases that pose a risk to humans. Murray says that although these viruses and other infectious agents are not new to the earth, many are new to human populations.

“Even in the United States, as populous as it is, there are still going to be diseases that we haven’t identified.”

–Byron Murray

“The viruses have been here for a long time, many centuries of time, perhaps even millions of years. Plants are infected with specific viruses, and all species of animals are infected with multiple kinds of viruses. We see many viruses that may or may not cause severe problems in their natural host, that can be devastating in another host,” he says.

The Ebola virus, which killed more than 100 people in a recent outbreak in Zaire, is thought to have originated in animals, says Murray. Researchers began focusing on the disease after outbreaks in 1976 and 1979 killed nearly 400 people. Yet they have never been able to identify the source or to offer hope to its victims.

“During these outbreaks in Zaire and Sudan, they looked at more than 3,000 different animals—more than 100 different species—to try to find the reservoir—how it was spread—and they never came up with definitive answers,” he says.

Murray says the deadly virus, which is spread by contact with body fluids and perhaps even by “aerosols” (coughing and sneezing), is an example of a disease that could reach epidemic proportions if it were spread in a major population center.

The United States experienced that vulnerability first-hand in 1989 and 1990, when research animals at a facility in northern Virginia were diagnosed with a strain of Ebola virus. It is believed that a shipment of monkeys from the Philippines carried the virus to the United States. The research company, a contractor for the U.S. Army, acted immediately to keep it from spreading.

“A specialized group of Army researchers decontaminated the building and closed it down. There were children across the street, and it’s not inconceivable that the virus could have been spread. We could’ve had a tremendous disaster,” Murray says.

In the United States, other home-grown diseases like the Hantavirus (which is spread by rodents) and Lyme disease (a bacterial infection carried by wood ticks) show even relatively populated areas are susceptible to emerging diseases.

“Even in the United States, as populous as it is, there are still going to be diseases that we haven’t identified,” Murray says.

Murray is concerned not only about emerging diseases that are moving from jungles and forests into villages and cities, but also about “reemerging” diseases, like tuberculosis and strains of streptococcus and staphylococcus, known as “flesh-eating bacteria.” Many emerge with new characteristics, including antibiotic resistance and increased toxicity.

“Flesh-eating bacteria has been around a long time, but it’s producing some new toxins now that are not quite the same. And tuberculosis is coming back onto the scene with drug resistance to five or six antibiotics. So we’re seeing diseases that we thought were controlled and eliminated reemerging in a population,” he says.

Murray says many strains of bacteria and viruses are developing resistance to current treatment methods. For example, HIV, which causes AIDS, has been shown to be increasing its resistance to the drug of choice, AZT.

“The virus mutates and becomes resistant quite readily. The strategy then is to give another drug that affects the virus at a different point in the virus’s infectious cycle so that you can use combination therapy. They use two or three kinds of totally different drugs, that affect totally different events in the cycle of virus replication. There was no reason to believe the virus would become resistant to those compounds, but it’s happened. Now you get multiple resistance,” he says.

While the medical community will have a difficult time keeping pace with these emerging diseases, the CDC hopes to control the spread of disease by monitoring disease patterns, improving the integration of lab work and disease study, providing information to the public, and strengthening community health programs.

“As we move into the next century, we face many challenges because a lot of things are changing. With environmental changes, world travel, changing demographics, and other parameters, we’re going to have to keep moving if we are to control the problem. It’s going to be a real challenge,” Murray says.

—Julie H. Walker