In the dead of an August night, Kurt F. Dickson (BS ’89) stood alone on the beach in Samphire Hoe, England, wearing just a Speedo and a BYU swim cap. As a spotlight from a boat offshore illuminated his body, Dickson raised his arm, and a horn blared in return. On that cue the 50-year-old former BYU swim team captain plunged into the bitter cold water to start his journey across the English Channel.

“It was dark, cold, and hard to get oriented,” he recalls. “I kept kind of swimming back and forth towards the boat. The first four hours I really wanted to get out. It was tough.”

Tough swims weren’t anything new for the emergency room doctor from Arizona. Dickson, who started competitively swimming at age 6, is now a 64-time U.S. Masters national champion. Two months prior to his English Channel attempt, Dickson had competed the 28.5-mile Swim Around Manhattan Island race.

With its shifting ocean currents, the 21-mile English Channel is a particularly challenging swim, and even the most experienced athletes rely on the guidance of boat captains. During a practice swim those currents pushed Dickson two miles off course, forcing him to walk back to his car in just his Speedo.

Not letting the currents get the best of him a second time, Dickson let the boat guide him through the water toward Cap Gris Nez, the northwest tip of France. On the boat, family members and an official observer from the Channel Swimming and Piloting Federation could barely see him splashing in the darkness.

Throughout the swim, Dickson’s wife, Catherine Read Dickson (BS ’88), lowered gel packets, oatmeal, and electrolytes down to him via a homemade feeding pole fashioned out of a golf-ball retriever. But Dickson didn’t stop long for nourishment. “It was just so cold,” he recalls. “You have to keep moving or you get hypothermic.”

Five hours into the swim, Dickson entered French waters. Wearing a shirt with the words Old Man and the Sea, Dickson’s daughter Kelsey Dickson Vogler (BS ’12), herself a former BYU swimmer, shared encouraging messages via a whiteboard she held off the side of the boat. As Dickson kept swimming, the French coast finally appeared on the horizon.

“The last five or six miles are tough because you can see France, but you see mirages out there,” Dickson says. “You think you’re close and start picking up the pace, but then you realize you’re not close at all. It messes with your mind.”

When Dickson actually did approach the French coast, Kelsey jumped into the water to swim the last 200 meters behind her father as he became the 1,802nd person to officially cross the English Channel solo, with a time of 10 hours and 23 minutes—the fastest official time in 2017. He scooped up a handful of rocks on shore to save as souvenirs and swam back out to the boat to cross back to Samphire Hoe.

Back in the UK, Dickson celebrated with Tim Powers, a former BYU swim coach who just happened to be serving there with his wife as a missionary. “He was proud of me,” says Dickson, “because it’s one thing to [swim the Channel] in your 30s or 40s, but I’m 50.”

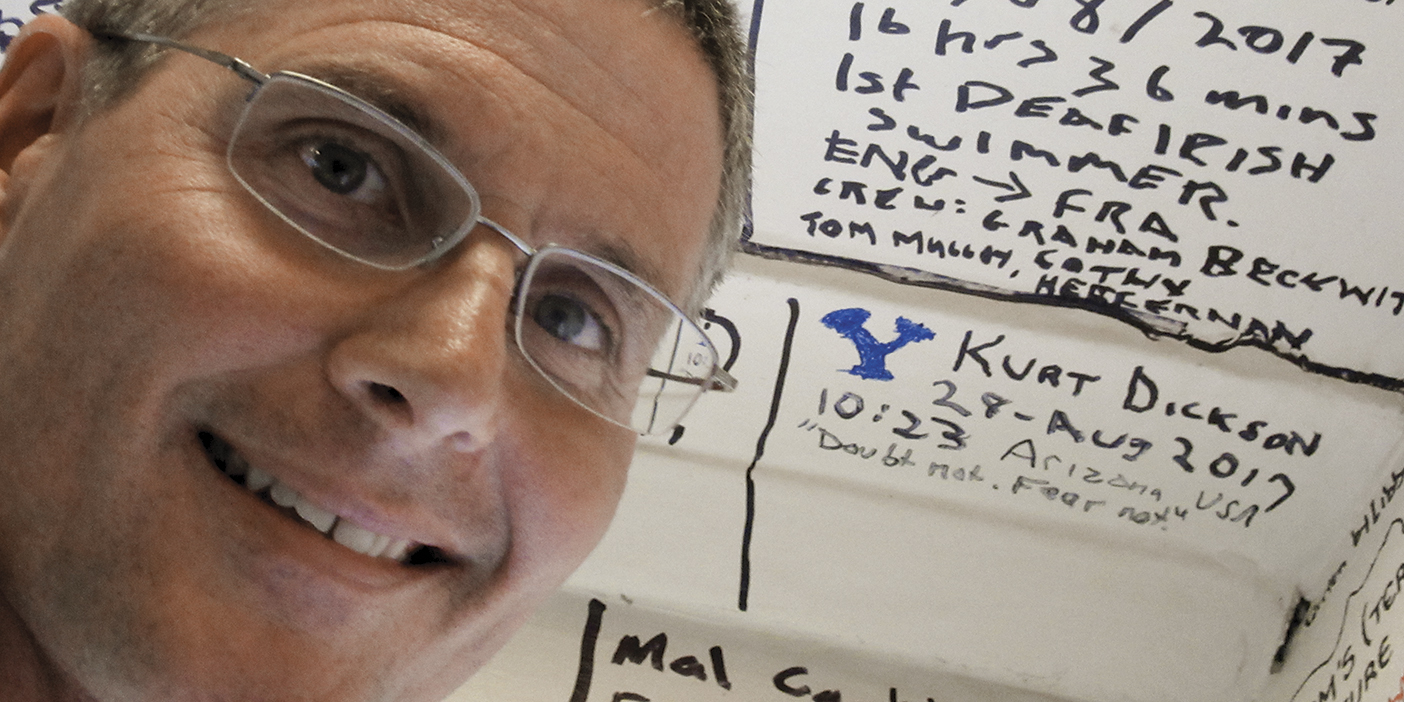

The White Horse Pub in Dover has a tradition of collecting signatures on the walls and ceiling from those who have swum the English Channel. On Aug. 29 Dickson added his, accompanied by a blue Y, his swim time, and the words “Doubt not, fear not.”

“[The scripture] reminded me of my Channel swim. Even though my family was right next to me, I was feeling so cold and alone. It really gave me spirit, because God was there for me,” says Dickson.

With the English Channel and the Swim Around Manhattan Island under his belt, Dickson needs only to swim the 20-mile Catalina Channel to complete the world’s Triple Crown of Open Water Swimming.

Some would call undertaking such arduous swims torture; Dickson calls it living. “I’d rather feel bad than nothing at all,” he says, paraphrasing a Warren Zevon song. “[These] swimming challenges, with the associated pain, help me feel alive.”