A Bridge to China

A Bridge to China

A bond forged 40 years ago was renewed this year by BYU’s largest-ever performing tour.

By Peter B. Gardner (BA ’98, MA ’04) in the Fall 2019 Issue

An endless stream of bicyclists, most clad in matching blue or green Mao jackets, clogged the streets; there was hardly a personal vehicle to be seen. In a city of nine million, apart from the occasional ancient temple or tower, there were no buildings over five stories. The Beijing that BYU student performers first encountered in 1979 was entirely foreign to them. After 30 years of political and cultural isolation, China was an exotic enigma to the students, and the Chinese had no idea what to make of these smiling young Westerners.

In the most unlikely of long shots, BYU’s Young Ambassadors became the first Western performing group to enter communist China, finding sudden fame and forging an improbable bond with the Chinese people—a friendship now 40 years strong. It’s a relationship marked by academic and cultural exchanges, faculty collaborations, long-standing study-abroad programs, and 30 repeat trips by BYU performing groups.

A lot can change in 40 years. Nowhere is that more true than in China, where the streets of its cities are still clogged, only now with high-end vehicles; where smartphone-obsessed youngsters sport Adidas, Zara, and Uniqlo as they ride state-of-the-art subways; and where the world’s second-tallest building now watches over more than 125 skyscrapers crowding the Shanghai skyline.

But some things haven’t changed, like the shared values of family, education, and harmony that first connected the BYU groups and their Chinese audiences. And so, to celebrate four decades of friendship, BYU decided to craft a special gift for their old friends in China—something bigger, grander, and unlike anything they’d ever shared before. In a word, something spectacular.

A Farfetched First

BYU’s first performance in China happened in the visitors lounge of the airport in Canton, with a huge painting featuring Chairman Mao above and a crowd of Chinese travelers stopped in their tracks by the spectacle. The impromptu show, given just minutes after the weary student group stepped off their plane, just might have saved the groundbreaking 1979 tour.

A year earlier no one could have imagined that a BYU performing group could even be there. It all began when BYU president Dallin H. Oaks (BS ’54) attended an October 1978 meeting where President Spencer W. Kimball called on Church leaders to find opportunities to engage China and other nations. Oaks’s mind went to the university’s performing groups.

“The idea was farfetched,” he later admitted in a BYU devotional. “At that time the United States had no diplomatic relations with China, and U.S. tourists were not welcome there.” It had been three decades since Mao Zedong established the People’s Republic of China in 1949, severing ties with the West. And Mao’s Cultural Revolution, set out in 1966 to rid China of traditional and bourgeois influences, only widened the divide. Although relations had begun to thaw in the 1970s, a performance tour in 1978 was impossible.

Even so, Oaks left the meeting and instructed his assistant, Bruce L. Olsen (BS ’63, MA ’65), to begin planning a tour to China.

Then in December farfetched suddenly became at least possible when U.S. president Jimmy Carter announced that the countries would renew formal relations on Jan. 1, 1979. Over the following months, BYU leveraged several well-placed contacts from Guam to Romania to secure an invitation from the All-China Youth Travel Service, though no specific performances were guaranteed. Now they just had to piece together a team from BYU’s already-booked performing groups.

Christy Bates Kirkland (’81) remembers the phone call from Young Ambassadors director Randall W. Boothe (MMu ’79). She’d just returned home after six weeks with the group on a performance tour to Canada and the U.S. Northwest. Boothe wanted her to come back to campus to join 19 other students from the Young Ambassadors and Lamanite Generation performing groups on a second six-week tour—this one to China. The catch? They had to throw together a show in less than a month.

So for three weeks, six days a week, Kirkland and the other students crammed Chinese culture and memorized narrations in Mandarin from 8 a.m. till noon and then from 1 to 8 p.m. rehearsed the singing, dancing, and costume changes for their complex numbers—including American show tunes, a Disney medley, and a hoop and fire-knife dance. Everything was coming together—albeit at 100 miles an hour—until a telegram suddenly slammed on the brakes.

Just four days before departure, the All-China Youth Travel Service sent a request: “Please bring only simple musical instruments for unofficial performances in schools or factories pending approval.” Boothe suspects the organization had seen BYU’s extensive packing list and become skittish about the scope of this artistic first.

“I was devastated,” he recalls. “We had a ton of equipment; we were ready to do a big show.” Without their costumes, props, and lighting and sound equipment, they’d have to rethink everything. Boothe and Olsen called Elder James E. Faust, who was to accompany the tour as a representative of the BYU Board of Trustees, lamenting the development. Elder Faust’s response: “Randy, where’s your faith?” The Lord, he assured, would open doors. They’d take everything as planned.

Still, when the BYU troupe arrived at the airport in Canton, the officials who met them were dismayed to see the pile of equipment. “Didn’t you get our telegram?” they asked.

Showing photos of the planned performance, Elder Faust explained that they just couldn’t give their friends in China the first-rate performance they’d prepared without costume changes, lighting, and sound equipment. He then beckoned to blond-haired, blue-eyed Cindi Whittaker (now Sainsbury [BS ’82]), a Young Ambassador. Trembling just a little, she stepped forward, smiled broadly, and delivered her narration in Mandarin.

The officials’ “eyes opened wide,” Boothe remembers. “They could understand her.”

Elder Faust then summoned other students to give impromptu performances of the song-and-dance numbers they’d prepared. Curious Chinese travelers soon circled around and watched from the balcony. When the students sang the Chinese folk song “Mo Li Hua,” the delighted spectators clapped and sang along.

The officials made a phone call. The equipment could come.

But whether the students would actually be allowed to perform for audiences beyond schoolchildren and factory workers was yet to be determined. That all depended upon a trial performance the next morning.

On the Fourth of July, the BYU group set up their equipment on a small stage in a dark and musty hall at the National Minorities Institute. Before them was a row of party officials, notebooks and pens in hand, quietly reviewing translations of the song lyrics from BYU’s proposed show. A handful of institute students decked out in colorful costumes had just performed for their American guests. Now it was BYU’s turn.

There was no clapping during the 90-minute performance, Boothe recalls. He remembers how the officials’ inscrutable seriousness contrasted with ear-to-ear grins from the young institute performers, who, despite their best efforts, occasionally let slip a little cheer.

“They had never seen . . . a fast-paced show like ours,” says Kirkland. “They especially loved our Chinese narrations.”

She says that, at the end of the performance, a spokesman rose and addressed the BYU group: “This is your first, and I hope not your last, visit to China. You, the youth, represent the future of our world and will raise our relations to new heights.” The BYU group, he announced, would perform two days later at Beijing’s Red Tower Theater.

“The Red Tower Theater was the most prestigious theater in China at the time,” says Boothe, who wondered how they’d find an audience of 1,600 in just two days with no prior publicity.

He needn’t have worried. The party invited all of Beijing’s artistic elite—musicians, ballet dancers, opera singers, actors—for a first glimpse of American culture. But the stakes were still high—the remainder of the tour, as well as future opportunities for BYU and other foreign groups, all depended on winning over this influential audience.

Undaunted, the next night the students stepped onto the sweltering stage (women waited just offstage with fans to cool the sweating performers) and launched into a presentation unlike anything their audience had ever seen, one full of lively songs, clever dance routines, and abundant smiles for the spectators.

“Fifteen minutes into the show, people were coming backstage telling us that ‘The important people in the audience are pleased,’” Olsen recorded. And they weren’t the only ones. The audience’s enthusiasm grew with each number, and, Olsen noted, they called back the Shenandoah song “Next to Lovin’ (I Like Fightin’ Best)” for three bows—and then insisted the students perform it again following the intermission.

“Prior to leaving for China, we were told not to expect anything but light, polite applause,” Olsen wrote, “but this audience demanded four encores and not only gave a standing ovation, but also held their hands high over their heads while clapping. It was the most enthusiastic response I have seen anywhere in the world. It was obvious we had passed the test.”

Foreign Fame

The sold-out, standing-room-only success of the inaugural BYU China tour in 1979 was beyond what anyone had anticipated. Even so, Boothe says the miracle is what happened the next year. It’s a good story—so good that President Kevin J Worthen (BA ’79, JD ’82) admits harboring suspicions that the claims had improved with age and many tellings.

As the story goes, when the Young Ambassadors were invited to return to China in 1980, BYU soon became a household name across the country, the best-known American university in all of China.

Timing was everything.

Until the late 1970s, television programming in China was limited to the afternoons and evenings and mainly consisted of political lectures and statistical lists. But in 1978 the country launched the party-backed China Central Television (CCTV), which quickly expanded its capacity and programming. The network was unboxing brand-new video cameras just as the BYU Young Ambassadors showed up for the second tour, in 1980. For CCTV the BYU tour was perfect—for practice and for new content. And so the camera operators followed the American students’ every move—from performing on stage to singing for youngsters on the street to fumbling with their chopsticks at dinner.

The resulting program ran again and again on CCTV for several years, and especially on holidays, when more Chinese people were sitting in front of television screens. Where the 1979 tour performances had introduced BYU to tens of thousands in China, the 1980 tour was seen—repeatedly—by a viewership well over 100 million. And with subsequent TV programs featuring later BYU performing tours, the university’s fame only grew.

But was BYU really that famous? On his first visit to China in 2016, President Worthen decided to test the claims, asking the vice premier of education and other older Chinese if they remembered the CCTV programs. To his surprise, as he recounted on a Chinese television program in 2019, they “confirmed this story—that they had this image of Brigham Young University and the United States because of our coming here.” The BYU students really had been ambassadors for the university and America.

And for song and dance.

One viewer, a 9-year-old named Qu La Jia, never forgot watching an elegant couple in tuxedo and sparkling gown dance across her television screen in 1985. She’d never seen anything like it before. “I was totally obsessed; I was mesmerized by the beautiful girls and handsome boys in the performance,” she recalls in the BYUtv documentary The Full Circle. “And the name ‘Brigham Young University’ stayed in my mind forever.”

Years later, as young dance instructors at the Guangzhou Art School, Qu and her husband, Chen Bing, met BYU dance professor Curt W. Holman (BA ’89, MA ’96), who had come to their school on an exchange. Impressed by his choreography and teaching approach, they eventually traveled to Provo, where they studied for a semester with BYU Ballroom Dance directors Lee (BA ’77, MA ’82) and Linda Baes Wakefield (’92)—the very couple Qu had admired years before on her television screen.

Now international world champion ballroom dancers and instructors whose teams have won Blackpool championships, Qu and Chen incorporate what they learned from their BYU friends, from the importance of preserving time for family to letting love show through in their dancing. Says Chen: “It’s more important to enjoy the process of competition than chasing awards.”

The reverberations of the early BYU tours and television shows continue today, four decades later. Among the audience at BYU’s first 2019 performance in Beijing was a college dean at the prestigious Peking University, carefully holding her ticket. Following the performance, she told her BYU friends that she intended to keep the memento with another treasured keepsake—the ticket stub she had saved from decades before, when she saw another performance by students from BYU, the famous American university.

A Different Miracle

Newark, New Jersey, is not in China. On this spring’s tour of the Middle Kingdom, that geographical fact would be noted—and bemoaned—again and again.

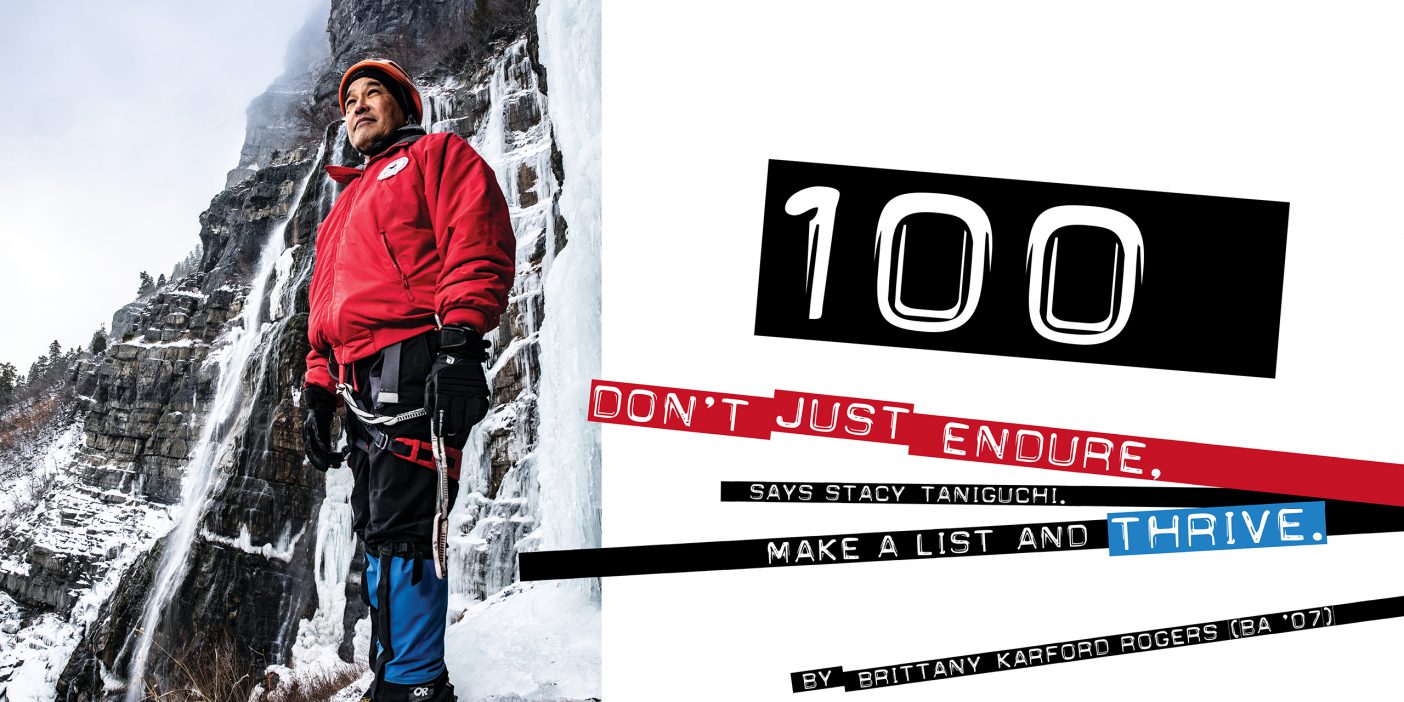

In nearly six decades of sending student performing groups abroad, BYU had taken on some pretty ambitious tours, often with as many as 35 performers; one tour even boasted 65. The 2019 tour? Eight groups combined for 167 performers in total. Throw in the tech crew, directors, and other support staff, and the company numbered more than 200.

“Forty years of friendship is very important,” explains Janielle Hildebrandt Christensen (BA ’67), who directed this year’s show. “We wanted to do something bigger, grander.”

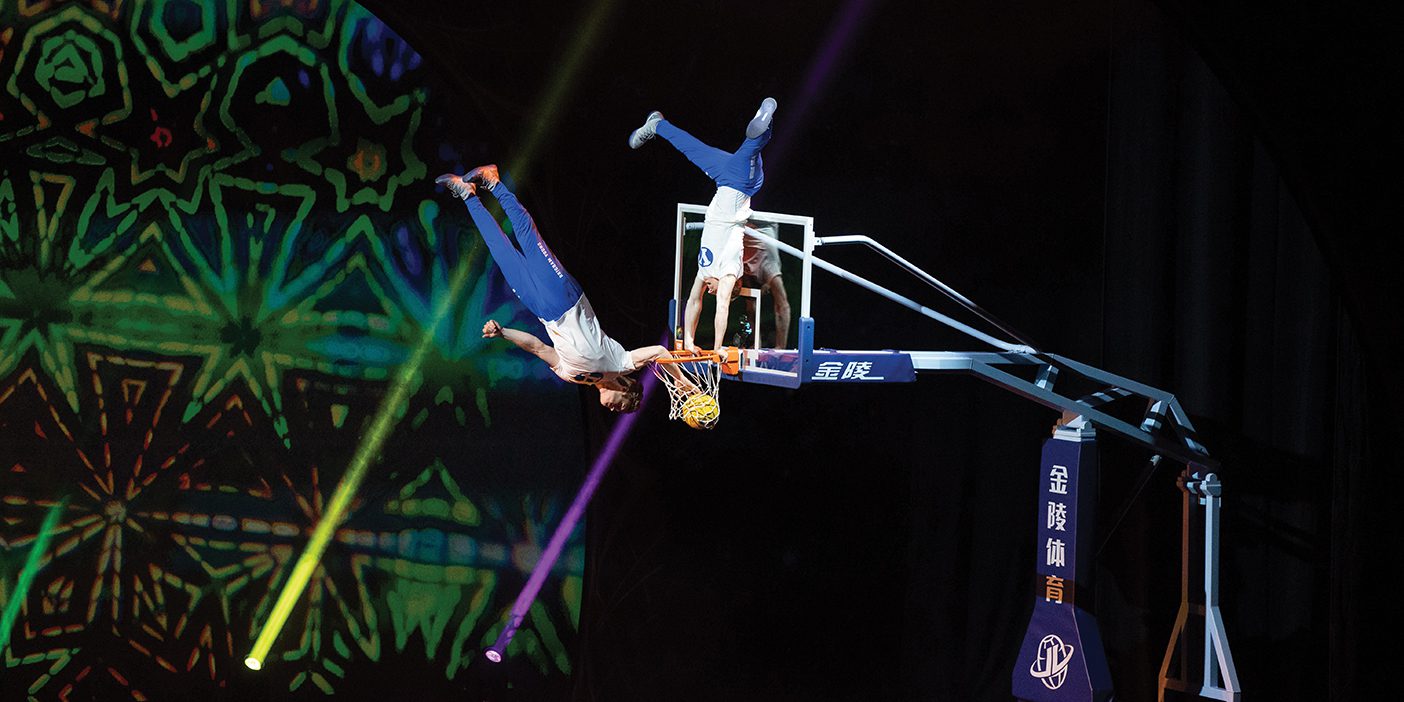

For two years Christensen, producer Michael G. Handley (BS ’83), and others worked to craft a show around various Chinese audience interests—including Broadway, Riverdance and American clog, ballroom dance, and a capella. Following the China edition of Jimmermania—when the former Cougar All-American Jimmer T. Fredette (BA ’16) led the Shanghai Sharks for three seasons—BYU decided to add in its dunk team for basketball-crazed Chinese audiences. Wanting more than just a variety show, the creators wove together a theme of shared values—family, learning, friendship, harmony, and love.

Calling it BYU Spectacular, they built a show to live up to the name, with pump-up lighting for the dunk team’s acrobatics, laser projections for a John Williams fanfare by the Chamber Orchestra, larger-than-life lion puppetry operated by Cougarettes for a Vocal Point cover of “Circle of Life,” and stilts and a Segway for a dreamlike Greatest Showman number by the Young Ambassadors.

With a production that big, there’s bound to be a hiccup or two. Cue Newark.

When technical director Travis L. Coyne arrived in Beijing five days before the first performance in May, he expected his 20 pallets of lights, sound equipment, scenery, staging, projectors, puppets, and trampolines to already be in country and working their way through customs. However, the shipping company told him there had been a delay, but—not to fear—it would all arrive shortly. Two days later, the equipment still not in China, the company admitted that the load had been bumped from its flight and sent instead to Newark. New Jersey. USA. There was no way it could arrive and pass customs in time for the Beijing performances.

“We were praying for a miracle . . . that all of our equipment would show up and they would release it immediately from customs,” says Christensen. “That wasn’t the miracle that we received.”

The miracle they got instead took place over 24 hours as the BYU team, led by Coyne and with the help of their colleagues from the China Performing Arts Agency (CPAA), tackled the lengthy list of items that needed replacing before Friday’s show. “We had teams of people scouring Beijing to track down . . . hardware and props and substitutions,” says Coyne. They rented sound-mixing and light boards, wireless mics, lighting fixtures, a screen and projector. They bought a bed from IKEA that they mounted on casters for a key prop. Remarkably, within four hours, they’d discovered a local dunk team willing to rent its trampolines and crash pad.

Although appreciated, the new equipment required extensive adjustments during rehearsals—especially for the dunk-team acrobats, who had to learn to leap from trampolines set at unfamiliar angles and with different spring and then land on a smaller, less-stable pad (“It was like going back 20 years,” says team coach David J. Eberhard). With the help of a local programmer, a translator, and her tech support back in Utah, lighting designer Marianne Shindurling Ohran (BA ’99) had to build simplified lighting cues from scratch in just four hours. And the performers had to re-choreograph numbers affected by props that just couldn’t be re-created, like the lion puppets.

By the time the first audience arrived at the Tianqiao Performing Arts Center, Coyne figures the team had rebuilt roughly 90 percent of what had been lost from BYU Spectacular, though everyone fretted that, without the remaining 10 percent, the show might be short on spectacle.

The audience quickly allayed those fears, responding warmly from start—when Young Ambassador McKenna L. Wright (’20) stepped on stage to open the show with a narration in her mission-language Mandarin—to finish—when Living Legends dancer Michael T. Goedel (’22) dazzled with an athletic hoop dance. Along the way, they clapped in rhythm to folk-dancer foot stomping, nearly fell out of their seats cheering the dunk team, and broke out in delighted applause when the orchestra played the first notes of the homegrown favorite Butterfly Lovers Concerto for a ballroom couple. If there was any doubt, the encore was the clincher, when the ensemble sang the beloved folk lullaby “Mo Li Hua”—just as the first BYU performers had done 40 years before—the audience tearfully singing and clapping along.

“By the end of the performance, [the audience was] just smitten by our students, by the special kind of exuberance that they have,” says Jeanette Eilskov Karnil Geslison (BA ’91, MA ’95), director of the International Folk Dance Ensemble. And yet, as well as the show went, she says the real magic happened just afterward in the lobby.

There, in a cacophony of chatter and laughter, the Chinese audience members posed with Cougarettes, got beatboxing demonstrations from Vocal Point’s Matthew D. Newman (BA ’19), and laughed with folk dancers. At the epicenter of the boisterous banter was the dunk team—4-year-olds, college kids, grandparents, and everyone in-between crowding in for photo ops. After observing his team’s shenanigans from the side, Eberhard says, “To watch these students embrace other people, their cultures, their lives, it’s overwhelming.”

“It all of a sudden makes sense to the students,” adds Geslison. “This is what it’s all about—to touch these people that we get to be with.”

Ultimately, Christensen says the difference between spectacular success and spectacular failure had little to do with visual pyrotechnics, puppets, or equipment, all of which wouldn’t finally arrive until the last stop on the tour, Shanghai. “We had [the students],” she says, “and they were our vehicle to bring the message, to bring the joy, to bring the light, to share the gift of friendship with China. They have never shined brighter.”