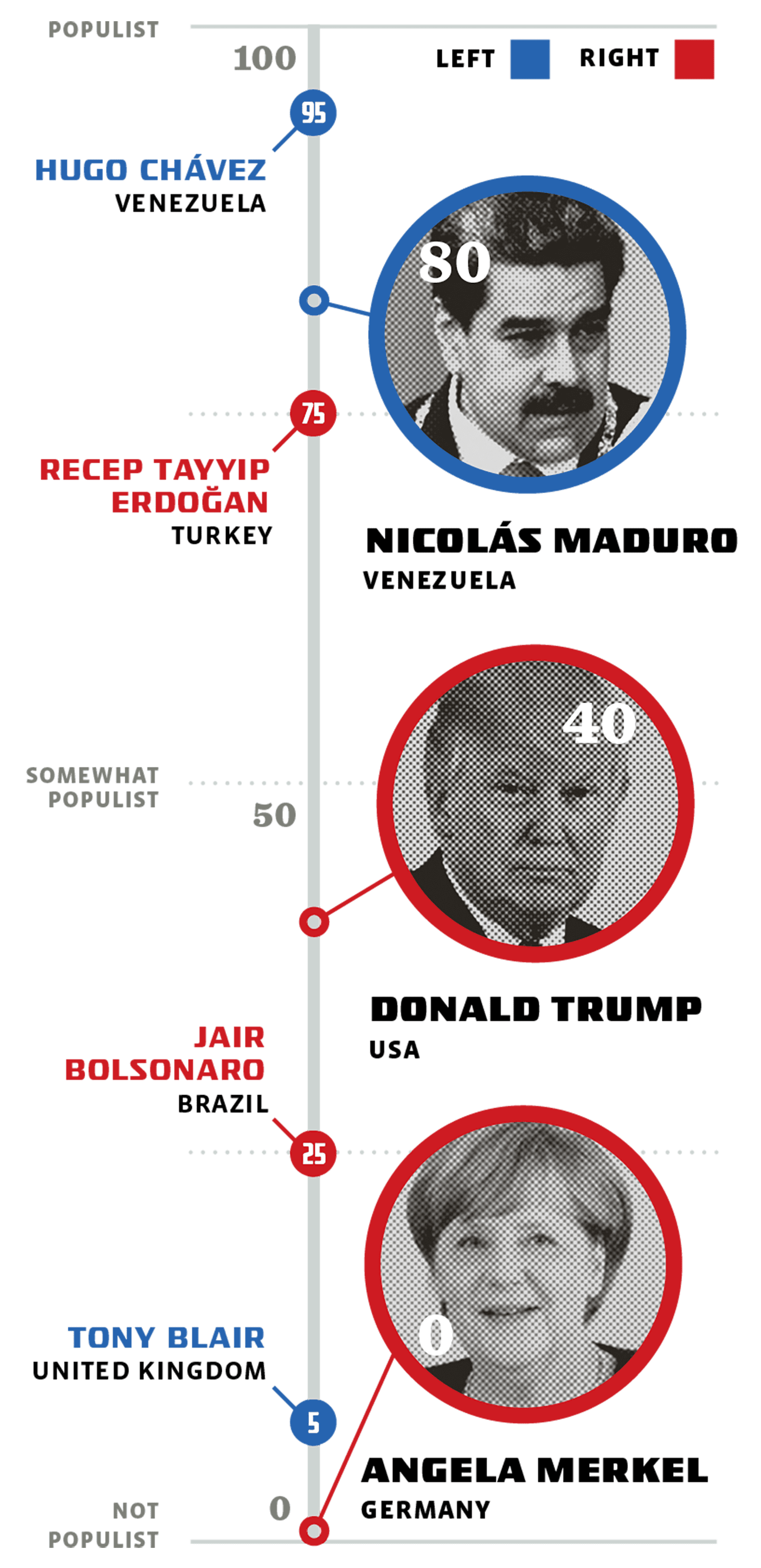

Hearing about populism more than you used to? You’re not alone. In 1998 the UK newspaper the Guardian used populist or populism around 300 times. In 2016? Nearly 2,000 times.

And definitions of just what populism means are also multiplying. To better understand this trend, the Guardian reached out to Team Populism, an international group of scholars led by BYU political science professor Kirk A. Hawkins (BA ’93, MA ’95). With help from scores of student researchers at BYU and other institutions, the team examined 20 years of political speeches from 132 leaders in 40 countries to determine who’s using populist rhetoric, why, and what effect it has on democracy. Their findings are available on the Global Populism Database, a joint project between the Guardian and Team Populism.

What Is Populism?

Hawkins says populism is a set of political ideas that pits the will of the people against a conspiring elite and tends to frame the world as a battle between good and evil.

Take lines heard in the last presidential election cycle referrencing “the corrupt establishment” or promises to “return power to you, the people.” Clearly populist.

Populism Isn’t Partisan

“There’s a little Hugo Chávez in all of us,” Hawkins quips, alluding to the extremely populist past Venezuelan president. Populist rhetoric, he emphasizes, can be found on both the political right and left. For instance, Team Populism’s analysis found that Trump and Democratic senator Bernie Sanders were equally populist.

Populism Is Good and Bad for Democracy

Team Populism found that an increase in populism can lead to reduced income inequality. And as citizens get more invested, they get new issues on the table and have increased voter turnout.

However, says Hawkins, populism doesn’t fix corruption and might even make things worse. “It justifies a lot of undemocratic excesses,” he says, like consolidating power in the executive branch, where leaders can roll back civil liberties such as freedom of the press and reduce election quality.

Populism also affects our attitudes. “It polarizes people,” says Hawkins. “The populist in power spends a lot of time demonizing . . . opponents, and the opponents react in kind. We call the populist and their supporters names and feed into their sense that they are the victims of a conspiracy, because we’re acting now like conspirators.”

Is Populism Dangerous?

Depends on whom you ask, according to Hawkins.

Some view populism as a natural result of global forces—globalization, economic recession, inequality, and corruption. Others, like Hawkins, view populism as a danger to the democratic process, particularly in the way it mistreats its opponents.

Speaking about that Chávez-esque streak in each of us, Hawkins warns, “You want to be self-aware enough that when issues come up that you feel strongly about, you can avoid demonizing your enemies and letting your anger get the best of you. . . . Don’t fall into that trap just because [others] have.”

—Kristen L. Evans (BA ’19)