You never forget someone who lovingly cooked for you.

“I like my pie in round pieces, hot or cold.”

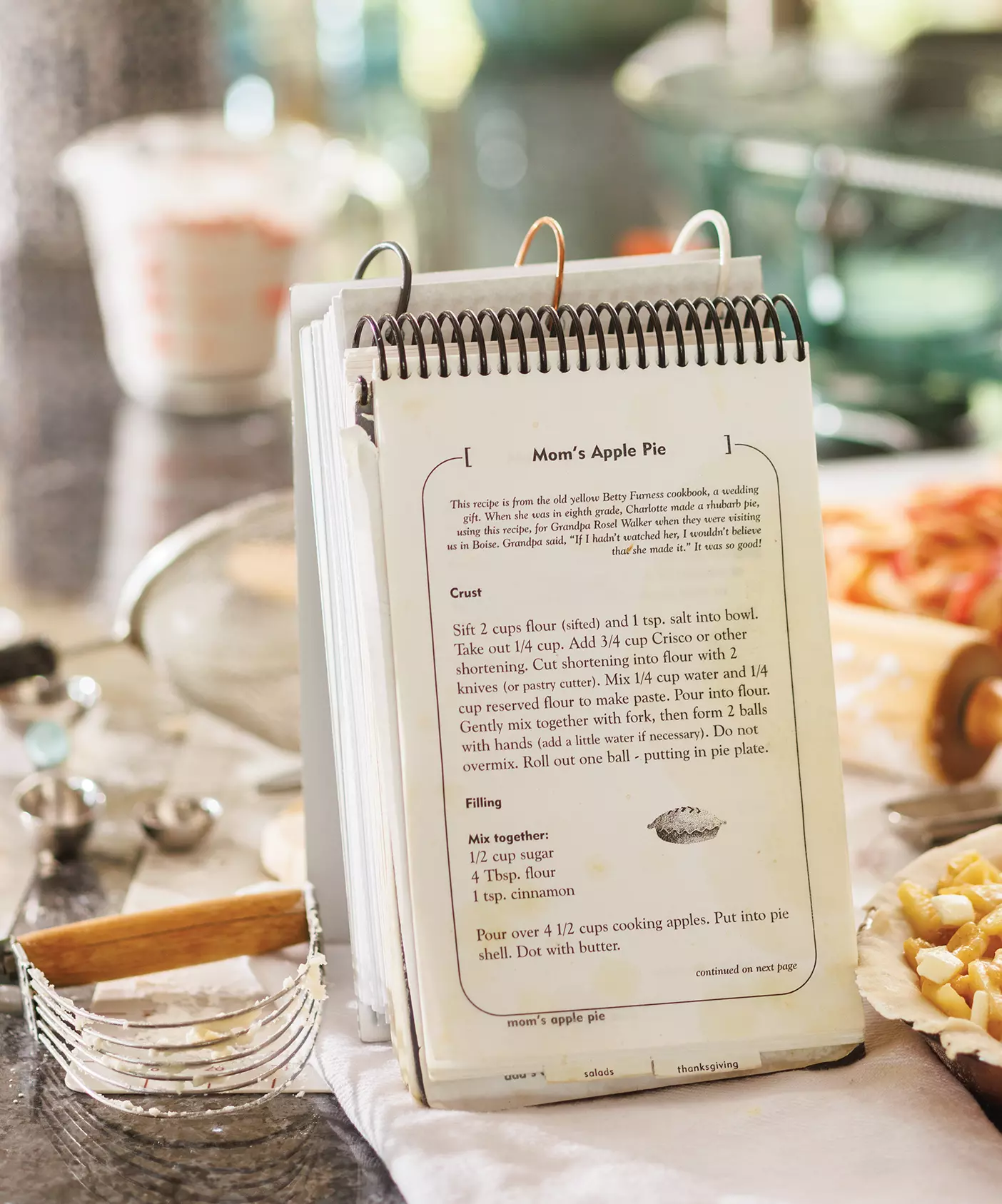

My dad’s oft-repeated pie preference echoed in my head as I topped juicy apple slices with cinnamon sugar and dots of butter.

After we arrived home from the hospital with our first son, apple pie seemed a fitting offering to celebrate an incomparable miracle. Having witnessed my wife’s courage in bringing a new life into the world, I felt insignificant, infinitely grateful, and more than willing to make dessert.

As I cut vents in the top crust, then crimped the pastry edges, I also thought of my mom’s patience when she first talked me through the recipe, which she had practiced and perfected. I learned her secrets for a flaky crust: use ice water and don’t overwork the dough.

Every time I make a family recipe, I glimpse the years of work in the kitchen and the love shared with me at the dinner table by parents and other relatives—efforts that occurred with little notice and appreciation from me until I left home.

As a home-starved missionary living in Ecuador, I missed the pancakes Dad cooked on Saturday mornings. So I wrote home to Idaho asking for the recipe, along with my mom’s version of Italian spaghetti and crêpe suzettes (a Christmas tradition).

I soon discovered that many of my dad’s recipes began with two cups of flour and a cup of shortening, which he scooped out with his bare hand instead of a measuring cup. For his faraway son, he took the time to quantify amounts and share some classic family food stories.

For a family dinner in the early ’70s, Dad whipped up his Spanish Delight, a simmering stew of canned tuna, sweet corn, and tomatoes topped with dumplings, a recipe he invented to feed the “thundering herd”—our family of 11.

Having covered and steamed the dumplings, Dad took the dish to the table and made a big production out of revealing his “masterpiece of culinary art” by raising the lid and saying, “Ta-da!” Inside the electric frypan, however, “lay six flat shoe tongues,” the result of him forgetting the baking powder.

“Fixing you food is how I tell you that I care for you.”

—Lin Walker

Years later, with two boys to feed, I typed up my grandmas’ recipe cards and asked my family for favorite meals and memories. Fellow foodie and sister-in-law Linda “Lin” Hinson Walker (BS ’71) sent Aunt Helen’s Smothered Chicken, which revealed: “Her name was pronounced Heelen (with a long E sound). This was because her father wouldn’t allow the word hell to be spoken in his home!”

The final product—bound with electrical connectors—was dubbed the Dad-Blasted Walker Family Cookbook, dedicated to my dad, who was an expert electrician, cook, and storyteller.

A few weeks before Dad died, he reminded me to “enjoy that sweetness while you can.” While he was reflecting on the love between spouses and the invisible bond of family, I believe it also applies to any offering from the heart. Every time I scoop out a handful of Crisco, I can feel it.

Before cancer also took Lin, she captured the joy of cooking for family on her food blog: “Fixing you food is how I tell you that I care for you, that I am sorry you had a bad day, that I’m glad that you had a great day. Food communicates . . . what I so often can’t find the words for.” I sense her spirit when we make Black Eyes of Texas, a hearty casserole perfect for feeding a big family, a needy neighbor, or missionaries far from home.

Not long ago I made my dad’s pancakes—using two cups of flour and oil not measured by hand—for my grandson, shaping the last of the batter into turtles. As the 1-year-old happily ate his first pancake, I could smell, taste, and feel dozens of Saturday mornings past.

In that moment I recalled standing with my dad at the back door of my childhood home, both of us flinging leftover pancakes like frisbees into the backyard for the birds to eat. That memory reminded me again to share the best family recipes— and food stories—with the next generation.

Mike Walker is an associate editor of Y Magazine.

SHARE A FAMILY STORY

In Letters from Home Y Magazine publishes essays by alumni about family-life experiences—as parents, spouses, grandparents, children. Essays should be 700 words and written in first-person voice. Y Magazine will pay $350 for essays published in Letters from Home. Send submissions to lettersfromhome@byu.edu.