The Diet of Champions?

In the stampede of competing dietary advice, how do you pick a winning eating strategy? BYU experts offer three different paradigms to consider.

By Amanda K. Fronk (BA ’09, MA ’14) in the Summer 2022 Issue

Illustrations by John S. Dykes

Dieting doesn’t work.

Okay, that may be a bit of an overstatement, but BYU experts say there’s reason for skepticism about trendy weight-loss diets.

“We can all name five people who have lost 50 pounds, but there are probably hundreds of other people who followed the same diet who did not lose any weight or gained it all back,” says dietetics professor Susan Fullmer (PhD ’04), a registered dietitian. Cell-biology professor Benjamin T. Bikman (BS ’03, MS ’05) agrees: “How many times have we seen the reunion tour for the greatest The Biggest Loser game-show contestants? We never do because they gain it all back.”

Indeed, research has shown that only about 20 percent of Americans who lose 10 percent of their body weight keep it off for more than a year.

But surely a solution is out there in the hundreds of diets and pills and lifestyle plans found in the weight-loss industry, with its projected 2023 global market worth more than $278 billion. Eschew fat, they say. No, fat is good! Intermittent fasting is definitely the way to go. But breakfast is the most important meal of the day. Eat fruits and vegetables! But not potatoes. Eat protein! Just no bacon. The conveyor belt of dieting advice is constantly churning, with each new idea seeming to contradict the last.

So what to do? With diet-influenced illnesses like heart disease and diabetes being among the leading causes of death in the United States, clearly our diet choices still matter.

It’s a complex landscape, and BYU experts can’t resolve all the confusion. What they can offer are frameworks to consider as you work through your nutritional quandaries. Rather than recommend any particular diet—that’ll depend on your goals and guidance from your doctor—these experts each argue for a different way to think about dieting, nutrition, and food.

Pace Yourself: Think Broad and Balanced

“Mother Nature didn’t put all the vitamins and minerals and nutrients we need in one food or food group,” says Fullmer. For overall health and wellness, she argues for filling our plates with a broad, balanced diet, sampling from the full buffet of offerings. “All foods can fit into a healthy diet,” she says.

Variety isn’t good just for getting your daily allowance of nutrients. A varied diet is also more sustainable than diets that go to extremes to bring about weight loss. “The more extreme a diet gets, or the more foods or food groups it takes out, the more difficult it is for people to follow for a long time,” she says.

Fullmer also recommends moderating our weight-loss goals, which are often unrealistic. When embarking on a new diet, “we think we’re going to lose 50 or 60 or 100 pounds,” Fullmer explains, but successful weight loss is usually closer to the 5–20-pound range. Though smaller, these losses can still have a big impact on health, lowering blood pressure and the risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

Fullmer says it’s also important to pace ourselves in our other efforts to improve health. We often make too many changes too quickly, she notes, and then “just fall back into undesirable habits really easily.” Here, too, avoiding extremes helps. She suggests starting with one or two small, measurable goals—like packing a lunch instead of eating from the vending machine or adding a vegetable to a meal—and then building on those new solidified habits to move to the next dietary or fitness goal. “Most people aren’t going to go to the gym and all of a sudden become exercise animals,” says Fullmer. “But they can walk. They can set some sort of realistic goal . . . to be more physically active, without training for a marathon.” There are many small steps toward health, but here’s the hard part: pick just one goal to work on.

When it comes to food choices, nutrition professor James D. LeCheminant (BS ’99, MS ’01) says we should stop gritting our teeth through extreme diets. Instead, he advises finding a smorgasbord of foods to stock your pantry and fridge so that appetizing and healthy options are readily available.

Landing on a diet that is nutritious and sustainable—and that you enjoy—can require experimentation. LeCheminant suggests trying out a variety of foods and seasonings to create your own customized menu of options. “Find an approach that works for you,” he says. “The mindset has to be you’re in it for the long term. What is a way of eating that you enjoy, that brings happiness, that brings your family together—the social aspect? What . . . can [you] sustain longer term?”

Don’t know where to start? LeCheminant and Fullmer point to the USDA’s MyPlate plan (available on the web and an app), which breaks down food groups like vegetables and grains, suggests daily amounts, and helps users customize their eating patterns.

Fullmer recommends diets that have been backed by one of the major health organizations to reduce the risk of chronic disease, like the American Heart Association; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; or the American Cancer Society. Three such eating plans are the Mediterranean, MyPlate, and DASH diets— “all really similar with just minor differences,” says Fullmer. These diets are plant based with room for meat and animal products. They promote eating a variety of fruits and vegetables of different colors and families and focus on eating whole grains more often than refined grains. These approaches protect against heart disease, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s and can even improve mental health.

While weight loss can occur with a broad, balanced, sustainable diet, Fullmer says the ultimate goal shouldn’t be weight but feeling better, having more energy, and creating sustainable habits. “The goal should be changing behaviors, not a dress size, not a certain weight on the scale . . . or a certain number of pounds lost.”

Get Metabolically Fit

The usual formula for weight loss is a simple one: calories in < calories out. In other words, eat less and exercise more so that you burn more calories than you consume. “If you’re just focusing on cutting back your calories, sure, you will lose some weight,” says Bikman. “But you’re also ensuring your hunger is growing every moment, and hunger always wins.”

As a cell biologist Bikman has his eye on another factor: insulin, the hormone that regulates metabolism and promotes glucose absorption and fat production. As a source of energy for our bodies, glucose comes from carbohydrates and sugars or, when needed, is produced by the liver. When we eat glucose-rich foods—like grains, starchy vegetables, and sweets—the pancreas releases insulin to transfer glucose from the bloodstream into cells. Excess glucose is stored as fat. Thus, ironically, body fat has less to do with eating fatty foods than with insulin’s response to carbs and sugars.

When insulin levels are high for prolonged periods, major issues can arise, says Bikman. Chronically high insulin levels can lead to insulin resistance—when cells become less sensitive to the hormone, resulting in both elevated blood sugar and insulin. And more of that blood sugar is converted into fat. Beyond changes in body fat, elevated insulin levels have been implicated in all sorts of maladies, most notably type 2 diabetes, but also dementia, cancer, heart disease, and infertility.

Most alarming: a 2019 study out of the University of North Carolina found that 88 percent of US adults were metabolically unfit—meaning they had some level of insulin resistance. “Diet is largely causing the problem,” Bikman says. But, he adds, “diet, then, can be the cure.”

For Bikman, it all comes down to reining in insulin levels. “If insulin is low, no matter what else you’re eating, the fat cell cannot help but shrink and thus fat mass will go down,” he says.

Bikman is quick to point out that he is not a dietician. Even so, his research has pointed him to eating patterns that can reduce the production of insulin.

To manage his own insulin levels, Bikman controls carbs, letting “the carbohydrates just be a filler in the diet.” The carbs he eats come from fruits and vegetables, which don’t raise insulin levels as much as foods that “come from bags and boxes with barcodes.” He notes that a low-carb approach has the backing of the American Diabetes Association, which in 2020 stated that there is “the most available evidence to support the use of low carbohydrate diets in improving glucose levels.”

In place of pasta and breads and sweets, he fills his plate with proteins—like eggs, dairy, and meat—seeking as much as 1–1.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight.

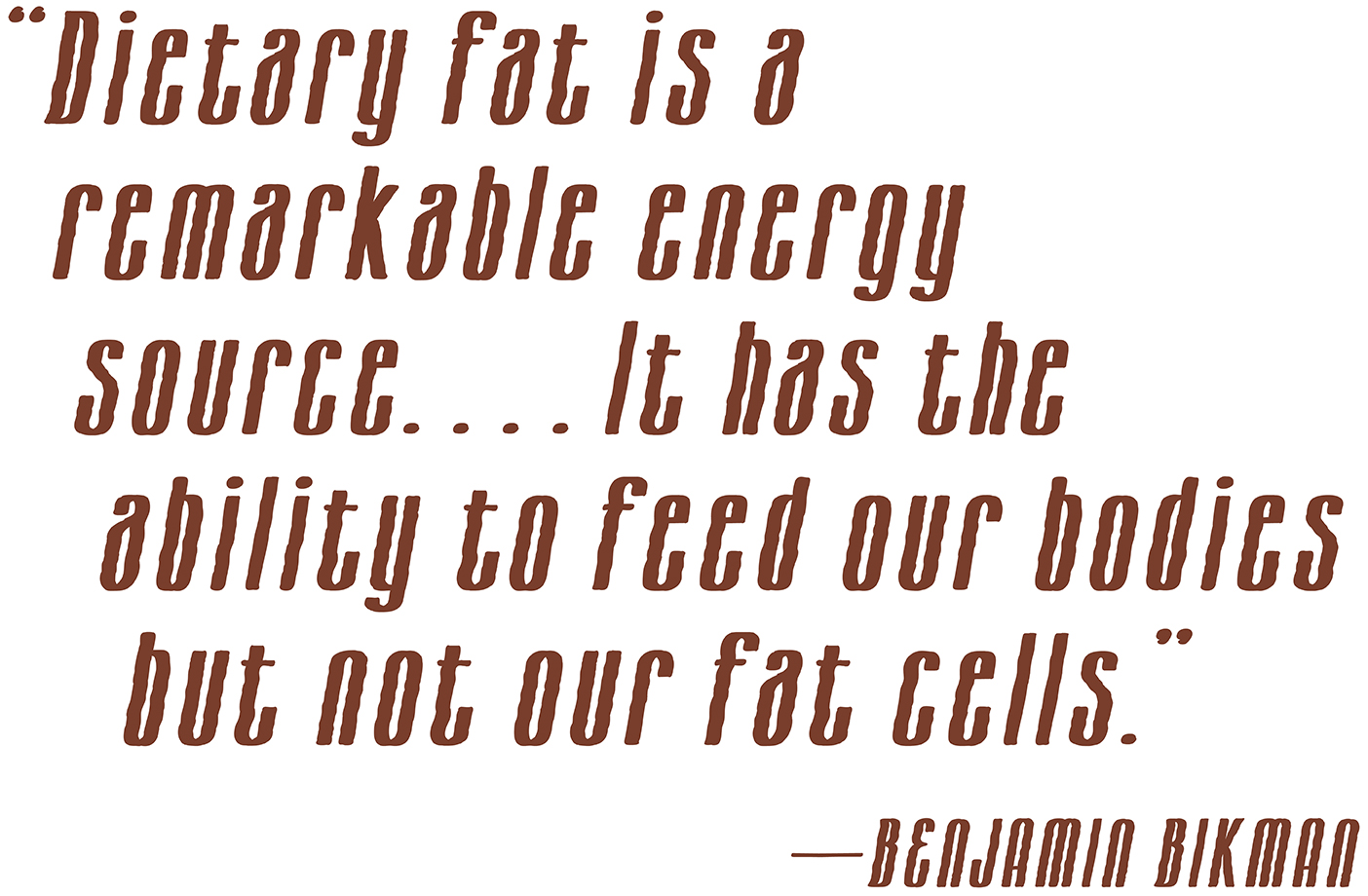

And he doesn’t fear fat. “We have a strong cultural aversion to dietary fat,” Bikman shared in a 2018 BYU forum, noting that Americans are eating less fat now than we did 50 years ago. “Dietary fat is a remarkable energy source. Because it has no effect on insulin on its own, in a way it has the ability to feed our bodies but not our fat cells.”

For Bikman, creating a healthy diet is not about calorie math—and certainly not about starving ourselves. It’s all about hitting the balance of proteins, fats, and carbohydrates that keeps insulin levels low. “If you can eat calories sufficient to satiate you . . . but at the same time keep your insulin low, well, now you have a perfect situation.”

Sit This One Out

What if the best approach to diet is not dieting at all? For Lauren M. Absher (BS ’07, MPH ’15), a registered dietitian nutritionist at BYU’s Counseling and Psychological Services, healthy eating has more to do with emotional and mental perspectives than it does with any specific eating plan,

per se. With her clients, many of whom struggle with body image or eating disorders, she uses intuitive eating (IE), an approach that centers on a person’s relationship with food rather than on weight loss. “Dieting is a quick fix that gives you rules to follow,” she explains. “Intuitive eating is throwing those rules out the window, with nutrition still in mind.”

Absher’s typical client is someone who has tried multiple diets, counted every calorie, lost weight, then gained it all back plus some. She knows which foods are “good,” “bad,” low fat, low sugar, or low calorie. She tends to think all-or-nothing when it comes to food; she restricts herself like she’s the champion of self-discipline and then binges like it’s her last meal. She thinks about food all day, but it is never enough. She is full of both hunger and shame. She has a love-hate relationship with food and just a hate relationship with her body.

![Designed quote by Lauren Absher: "Intuitive eating is throwing [dieting] rules out the window, with nutrition still in mind."](https://magazine.byu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/pg32_Intuitive_quote_1404x500.jpg)

These problems, says Absher, represent the drawbacks that can come from years of dieting. “Most of the clients that I work with [have] developed a toxic relationship with food and with their bodies because of dieting.”

Intuitive eating can heal those emotional relationships, says Absher. It has physical health benefits too. The restrict-binge cycle triggered by many traditional diets can contribute to insulin resistance, which leads to type 2 diabetes. IE evens out eating patterns so this cycle doesn’t occur. Rather than avoiding sugar completely, IE adherents defuse the urge to binge large amounts of sugar by having more freedom to eat smaller amounts as part of a satisfying diet.

Intuitive eating also counters the weight gain that can be brought on by chronic dieting. With dieting, “a lot of times . . . the adrenal glands and the thyroid shut down from the calorie restriction. That can then promote weight gain,” explains Absher. “Some people’s bodies will rebel so much against dieting that they will start to store weight, even with severely [restricted] calories.”

So does intuitive eating mean that any eating pattern will promote health? Not quite. But Absher does begin her therapy by giving her clients permission to eat perceived forbidden foods. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner—along with small snacks in between—are all on the table. Once clients have regulated their eating patterns and are getting adequate calories, Absher teaches them to notice their hunger and fullness cues. And with hunger and satisfaction cared for, clients can then work on being around formerly forbidden foods without feeling out of control.

Though intuitive eating does away with traditional diet rules, it is not “eating with reckless abandon. It’s not dismissing nutrition,” explains Absher. IE is about getting in tune with the body’s hunger, cravings, and response to foods. Some people think that IE is someone craving cookies all day and then eating cookies all day, Absher says. “Well, if someone eats cookies all day and they listen to their body, their body’s going to tell them that they’re sick from eating cookies all day.”

Absher says that diets fail in part because they are focused on a single objective—weight loss—rather than the many other aspects of good health. “Do I have clients that will lose weight on intuitive eating?” Absher asks. “Yes. But do I use that as a measure of success for healing their relationship with food or health? No.” Instead, she looks to results like lower cholesterol, improved triglyceride and blood-sugar levels, and better liver function. “When clients want to give up on behavior change because weight isn’t going down, I help them identify the benefits of making changes that promote physical and mental health, regardless of weight,” she says.

Perhaps the best outcome of intuitive eating is peace, says Absher. For those who have worn themselves out “constantly thinking about food and their bodies,” she says, “intuitive eating can really heal [these] relationships.”

Feedback Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.