The Problem We All Live With

The Problem We All Live With

BYU professors reflect on race relations as they respond to Norman Rockwell’s painting of civil rights icon Ruby Bridges.

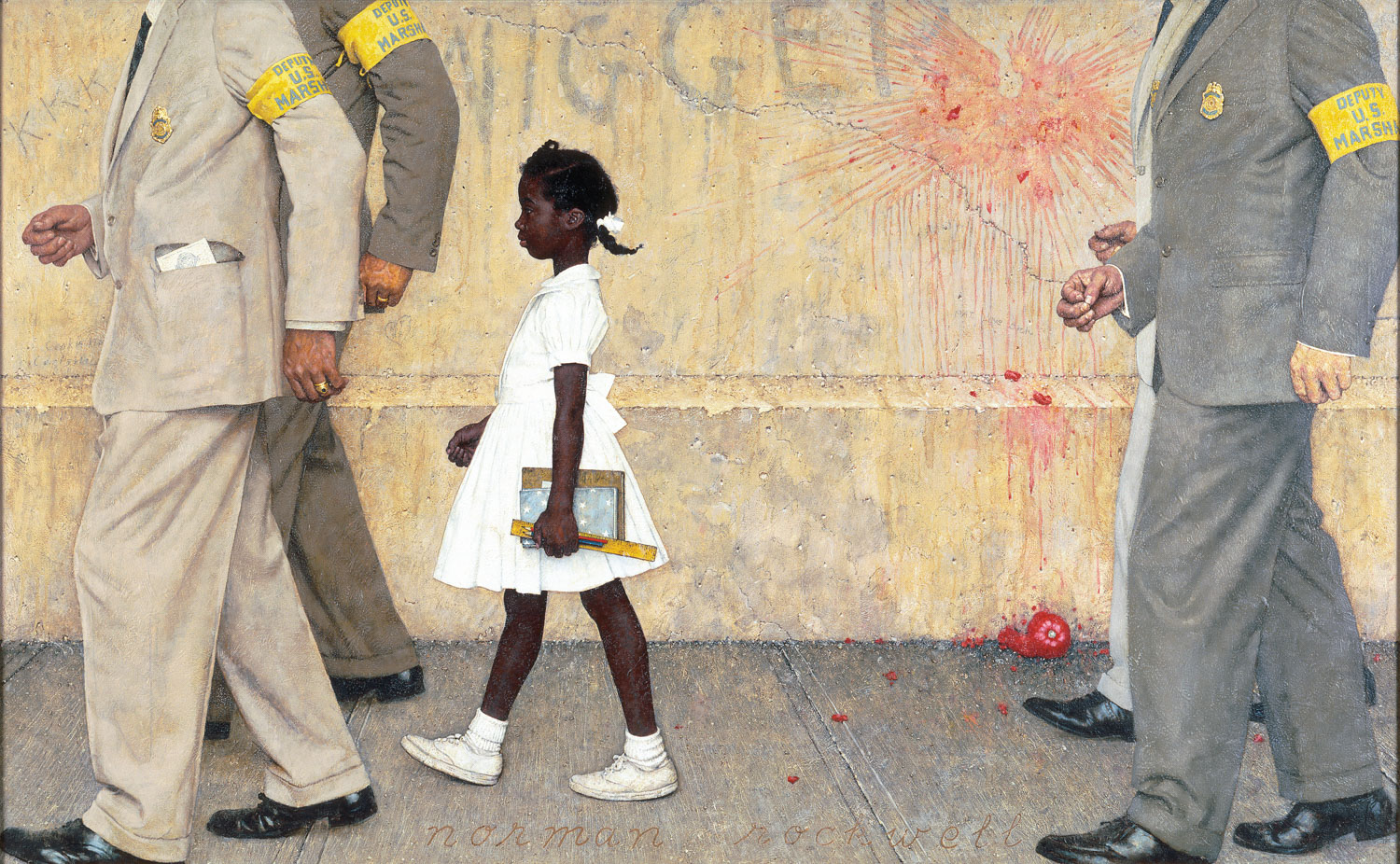

In 1960, escorted by federal marshals, 6-year-old Ruby Bridges became the first black child to attend the newly desegregated William Frantz Elementary School in Louisiana. The moment—captured in the above Norman Rockwell painting The Problem We All Live With and published in the Jan. 14, 1964, issue of Look magazine—made Bridges an icon of the civil rights movement.

In conjunction with the painting coming to BYU as part of the 2016 BYU Museum of Art exhibit American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell, BYU Magazine invited professors across campus to respond to this classic American image. Their reflections—academic, personal, poignant—underscore the painting’s continued relevance.

A Problem We All Still Live With

By Matthew E. Mason, Associate Professor of History

Both the title and the publication year of Rockwell’s The Problem We All Live With are significant. Although the painting depicts an event that took place in 1960—when Ruby Bridges first attended a previously all-white New Orleans public school—it first appeared in January 1964, when it was published in Look magazine. At that time, the civil rights movement had questions of racial equality on the minds of most Americans—the Civil Rights Act would be enacted six months later. The present-tense title of this painting would thus have spoken to magazine readers despite depicting an event from more than three years before.

So would the idea that it portrayed “the” problem of their day. An April 1963 Gallup poll found that only 4 percent of Americans put race relations at the top of the most vital issues facing their nation. But in October 1963, after the dramatic events in Birmingham, Ala., and the iconic march on Washington, that number had climbed to 52 percent.

Both in its present tense and in its universal application, the title of the piece still speaks to us today.

The idea that racial inequality was something all Americans lived with, however, would have been more challenging to many of those readers. From the time Northerners abolished slavery in their own states in the late 18th century, it had been far more common for them to think of racial inequality as a Southern problem than as a national problem. To be sure, civil rights leaders had long made the case that it was of national, not just regional, concern, and many Americans were deeply embarrassed when images of the violent suppression of the civil rights movement traversed the globe. But those images emanated from indisputably Southern places. So the title of this painting boldly embraced the controversial notion that all Americans, black and white, Northern and Southern, lived with the problem of racial prejudice.

“Only when people feel a personal connection to a problem will large numbers of them do anything to try to solve it.” —Matthew Mason

Both in its present tense and in its universal application, the title of the piece still speaks to us today. For a brief moment in 2008, overly hopeful voices proclaimed that the election of Barack Obama as America’s first black president heralded a “post-racial America.” Headline after headline has since proclaimed the sad truth that race remains central to American life. And those headlines have described events from every part of the United States. It remains a “problem we all live with.”

People do not generally acknowledge this, however, until the problem directly affects them. As I was writing this essay, for instance, news broke that BYU’s anticipated football game against the University of Missouri was in jeopardy due to protests over racial issues on the Tigers’ campus. Those protests had been ongoing for some time, but not until African-American football players stopped preparing for the BYU game—and were soon joined by their coaches and teammates—did these events make headlines in Utah. It is also telling that Utah’s Deseret News ran stories about the resignation of the president of the University of Missouri in the sports section, capturing well how and why Utahns were paying attention to what previously had seemed an abstract and distant problem. This recent episode teaches an important lesson that Rockwell grasped with his painting and his title: only when people feel a personal connection to a problem will large numbers of them do anything to try to solve it.

The Problem and the Solution

By Terrance D. Olson (BS ’67, MS ’69), Emeritus Professor of Family Life

When I first saw Rockwell’s painting The Problem We All Live With, I was drawn to the dignity of the girl in the white dress—to her seemingly determined walk. And I wondered how she held up under the problem she was living with. Unlike the title of the painting, young Ruby Bridge’s problem was not abstract or generalized. As the target of hatred at 6 years old, she lived it. I wanted to know more about this first grader and what it meant to her to walk past crowds who were screaming obscenities and death threats.

“Please, God, try to forgive those people.” —Ruby Bridges

Robert Coles, a Harvard psychiatrist, visited regularly with Ruby and her parents during this time and later gave insight into her perspective. He thought he understood the reason for her resilience, but he recounted that one night Ruby’s mother startled him by saying: “You’re the doctor. . . . You know what to ask children. But my husband and I were talking the other night, and we decided that you ask our daughter about everything except God.” Coles sat there silent and uncomprehending. [1] He had considered spirituality irrelevant to his psychological assessments.

I have read several versions of what Ruby said to Coles when he finally asked what faith had to do with her determined walk. The main thought she expresses in each is, “Please, God, try to forgive those people. . . . They don’t know what they are doing. . . . Just like you [forgave] those folks a long time ago when they said terrible things about Jesus.” [2] Ruby, a little girl, took her faith in God seriously. Rather than becoming hard-hearted toward her tormenters, she prayed for them and asked God to forgive them.

In my work with families across decades, I have found that faith and forgiveness typically go together. Ruby’s compassion, prayerfulness, and forgiveness are humbling to any of us adults who may have forgotten the key to solving the kind of problem Ruby faced. Her faith and forgiveness were a blessing to her, even though they were unknown to or unappreciated by her tormenters.

In moments when I feel attacked and justified in my hardness against others, I can look to Ruby. I can see both her faith and her forgiveness, and they awaken me to my own faith and commitment to forgive. My experience is that loving God and my neighbor are the most common starting points for forgiveness. Perhaps these are solutions we could all live with.

[1] Robert Coles, Harvard Diary (New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, 1988), pp. 135–36.

[2] See Coles, The Story of Ruby Bridges (New York: Scholastic, 1995).

Striding Forward

By Cheryl Bailey Preston (BA ’75, JD ’79), Professor of Law

I was 8 years old and living in Provo when Ruby Bridges was escorted into a New Orleans elementary school by federal marshals on Nov. 14, 1960. Perhaps at the doctor’s office, four years later I saw the January 1964 Norman Rockwell image The Problem We All Live With. The image seared itself into my mind. I remember seeing myself as that girl. I had worn the same dress, although mine was light blue—the same flouncy bow in the back, full skirt, puffed sleeves, and Peter Pan collar. My mother took great pride in ensuring that, when I left the house, every hair on my head was slicked tight into some ponytail or braid and tied with a bow. I too had a wooden ruler and wore white Keds with socks.

“Feeling empathy is a first step, but mustering resources—time, energy, attention, money—to do something positive requires much more.” —Cheryl Preston

Although my family had purchased a small black-and-white TV in 1957, I have no recollection of seeing racial tensions before my encounter with Rockwell’s depiction. I don’t know who explained Ruby’s predicament to me, but I felt it in my heart and in my stomach. The ruling of the Supreme Court and the protection offered by the marshals flanking Ruby became core to my patriotism: in the United States the strength of government is used to protect the small and the powerless.

Later, in a BYU political science class, Professor Stewart L. Grow had us identify which level of government we most trusted to do the right thing. Although my family espoused a general distrust of the federal government, I believed in it—and Ruby was my reason. Of course, from the vantage point of age and education, today I see more nuances in governmental and judicial authority; nonetheless, don’t tread on Brown v. Education!

Today that pride, however, is mingled with personal disappointment. As an adult, I am overwhelmed with the realization that my family lived during the Jim Crow era and did nothing to confront inequality. I was a teen and college student during the civil rights struggle and did nothing but feel incensed. Feeling empathy is a first step, but mustering resources—time, energy, attention, money—to do something positive requires much more.

When I first saw the image, I saw myself as Ruby. Now, I can be the marshals. I can take a stand in front and in back of the powerless and stride forward into those who hate on behalf of those without voice, confident it is the right thing. Note that the marshals are not armed. Their strength is not in a weapon. My ability to help, similarly, is not in force or violence. As a law professor, my influence comes in teaching nascent lawyers that their calling is to use their access to government and courts to promote righteousness, to speak for the voiceless, to stand between evil and what is small and tender.

Still Integrating

By Jacob S. Rugh (BS ’01), Assistant Professor of Sociology

Growing up on Chicago’s South Side, I was unaware of my exceptional experience regarding race. Half the students at my elementary school were black, one-third white, and the remainder Latino and Asian American. I sang the words to “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” at school assemblies. At my high school, four in five students were black. At many track meets I was the only white person around.

In my Church congregation, leaders included a great-granddaughter of black slaves, a native Spaniard, a black military veteran, an immigrant from Hong Kong, a black descendant of Thomas Jefferson, and the first black woman to be a sergeant on the city police force. At ward Christmas parties Santa Claus was often black. I learned the gospel from blacks and whites involved in the civil rights movement. We would visit those in racially isolated all-black housing projects, since demolished.

“The problem of the twentieth century will be the problem of the color line.” —W. E. B. Du Bois

I was certainly aware of race, but I still didn’t grasp “the problem we all live with.”

One summer my dad drove me beyond the city limits to visit a place like I had never lived before. The houses were different. Very few people were walking. And every face was white. My dad announced, “These are the suburbs.” Immediately fascinated, I exclaimed, “Dad, I know these—we studied them in school!” Then, after living for 15 years in integrated housing, schools, and church congregations, our family moved to an affluent suburb in Minnesota. After later stints in Harlem, New York, and a Spanish branch in New Jersey, the problem came into focus for me: racial segregation.

W. E. B. Du Bois, a founder of sociology, presciently observed in 1903, “The problem of the twentieth century will be the problem of the color line.” In my own research I have shown how racial segregation perpetuates racial inequality in home ownership, neighborhood quality, life expectancy, and wealth. Past policies of racially exclusionary housing cemented the color line. Due to such practices and current patterns of segregation, today the average white family owns 13 times the wealth of the average black family.

Because most neighborhoods remain segregated, schools are also segregated and inequality endures. The elementary school that Ruby Bridges bravely attended had zero white students two generations later. Research shows that black-white segregation will be around for another three generations. However, there is some hope. Military towns, college towns, and cities that actively encourage affordable and mixed-income housing in affluent areas have integrated much more rapidly. Children who attend integrated schools not only tend to do better academically but are also much more likely to choose to live in integrated neighborhoods as adults.

Segregation may still be a problem we all live with, but integration may be an answer—one that my life and work have shown is worthwhile.

No Easy Walk to Freedom

By Lane Fischer (BS ’79, MA ’82), Associate Professor of Counseling Psychology and Special Education

My father was a Jew. He became a Latter-day Saint after privately studying the Book of Mormon. I am a Latter-day Saint, and I am from the tribe of Judah. My family history sensitizes me to my forefathers’ travail. It is a common travail.

In the 19th century, Eastern European governments were openly anti-Semitic. Indeed, between 1885 and 1898 Romanian governmental sanctions increasingly restricted Jews’ schooling and presence in the professions and trades. The government rigorously enforced prohibitions on any trade with Jews. And so Jews began to starve. In 1899 the wheat harvest was poor. Economic depression set in. As before and after, the Jews were scapegoated. A brutal pogrom was carried out in Iasi, Romania.

With no hope of civil rights or protections in their home country, Romanian Jews began to flee on foot. They were called fusgeyers—foot-goers. Year after year, Romanian fusgeyers would set out for the West after winter broke. After climbing through the Prislop Pass in the Carpathian Mountains, they still had to brave the perils of other empires’ anti-Semitism. There was no easy walk to freedom.

“This demands that I extend liberty to all of God’s children.” —Lane Fischer

My great-grandfather Morris Schreiber was a fusgeyer. At 21, in 1900, the tinsmith walked out of Bucharest with two brothers and a sister-in-law. They left their parents behind, never to see them again. They walked 1,000 miles from Bucharest to Amsterdam. Kindly and powerful helpers aided them along the way, and they arrived at the Poor Jews’ Temporary Shelter in London on July 8. Philanthropic transmigration funds allowed them to board a converted troop carrier in Liverpool, bound for Canada. On July 24 the immigrants arrived in Montreal, where they were supported by a wealthy Jewish baron in Germany, who provided educational and employment opportunities. Morris worked his way south on the Great Lakes shipping lanes, eventually landing in Chicago, where he married my great-grandmother Schaindel Blumenfeld, who also had escaped Romanian anti-Semitism following the pogrom in Iasi in 1899. Morris and Schaindel had a daughter who had a son who became a Latter-day Saint who had a son who is a Latter-day Saint and is from the tribe of Judah.

My Jews walked 1,000 miles across Europe to escape bigotry. My Latter-day Saints walked 900 miles across America. I claim the legacy of both. This demands that I extend liberty to all of God’s children: “He inviteth them all to come unto him and partake of his goodness; and he denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female; and he remembereth the heathen; and all are alike unto God, both Jew and Gentile” (2 Ne. 26:33).

Seeing in Color

By Kate R. Johnson, Assistant Professor of Mathematics Education

When race comes up, a lot of people say, “I don’t see color,” as though that erases the need to acknowledge it at all.

Imagine Norman Rockwell’s painting The Problem We All Live With in black and white. The splat from the red tomato on the wall fades into the background. The armbands and badges become unremarkable parts of the marshals’ apparel. And yet, removing the color does not remove the hateful letters on the wall or diminish the little girl’s predicament.

“I choose to see in color.” —Kate Johnson

If the girl being escorted by the marshals into her newly desegregated school arrived suddenly in a space where people told her that she was the same as everyone else, how would she feel? Her experiences up to that point told a different story. Most children do not need an escort to guide them through a toxic mob. With the shouting still echoing in her ears, she might look at her mathematics classwork, she might try to concentrate on the teacher, but she would wonder: “Am I really the same? Am I wanted? Does it matter who I am and how I feel?”

“Am I really the same? Am I wanted? Does it matter who I am and how I feel?”

When I was a high school mathematics teacher at a school for the deaf, American Sign Language was the primary language for communication. Suppose I held the stance, “I don’t see deafness.” Standing in front of my students, I could have explained the mathematics concepts in perfect English, but it would not have mattered. My mouth would have moved while my students’ eyes were frantically searching for meaning. They might have been prompted to ask, “Does it matter who I am and how I learn?”

Consider these recent hashtags: #blacklivesmatter #whitelivesmatter #alllivesmatter. Black. White. All. People line the streets in protest. The air is heavy with anger, disgust, and confusion—each side asking, “Does it matter who I am and what my experiences are?”

Ignoring color (or anything else about another person) has done little to help me build meaningful relationships with those who look or hear or see differently than I do. Focusing on similarity obscures my ability to deeply understand someone else and hinders my development of love by making me think I know another’s experiences. Trying to view us all as the same requires people to conform to a single reality. Instead, I can acknowledge and investigate differences, choosing to have my new awareness and allowing it to impact my interactions with others. I am here to learn to become like my Father in Heaven and Jesus Christ—to love others while honoring individual differences.

I choose to see in color.

Art Credit: The Problem We All Live With, 1964, by Norman Rockwell, Norman Rockwell Museum Collections