Alumni in a dynamic BYU program are using indigenous arts to enrich Utah classrooms.

An elementary teacher attending an arts-integration workshop calls her husband tearfully from the bathroom. “Come and get me,” she pleads. “I can’t draw. They’re going to make me draw!” He encourages her to buck up and get back to class. She does, and in two hours paints a still life that fills her with pride. Soon she’s taking her students to the BYU Museum of Art. In eight months she’s teaching art to kids. In two years she’s presenting at conferences. She’s progressed from fear to skill to leadership.

“I could name 25 [such] teachers right now who have told me that these arts programs have changed their lives,” says Cally Johnson Flox (MEd ’12), program director of the BYU Arts Reaching and Teaching in Schools (ARTS) Partnership. The initiative was born in 2005, when the McKay School of Education and the College of Fine Arts joined up to strengthen education in public elementary schools through arts-focused professional development for teachers. “‘I’ve found who I am,’ [teachers] say. ‘I respect my students more. I have more strategies for reaching individual students. It kept me in teaching,’” relates Flox.

“We answer the question, ‘How do I integrate the arts in the classroom, use it to support student learning, and deepen class, school, and community culture?’” says Heather Gemperline Francis (BA ’13), director of research and development.

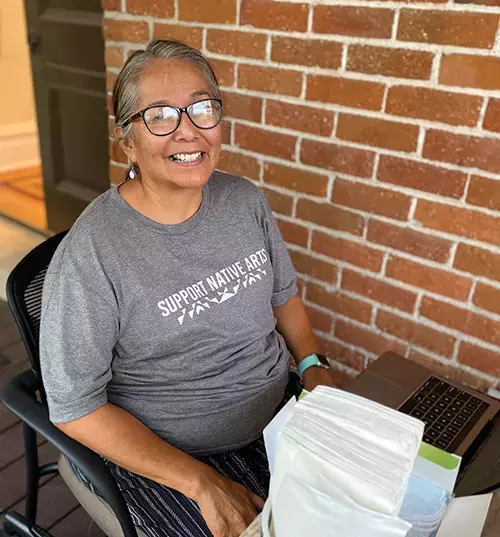

With such integrations in mind, in 2018 the partnership introduced a new tool—the Native American Curriculum Initiative (NACI), which teaches teachers how to include the art of indigenous peoples in their classrooms. Brenda A. Beyal (BS ’83, MEd ’99), a Diné (Navajo) schoolteacher with decades of experience who manages NACI, shows how the arts fit in across the curriculum—improving student engagement, understanding, and mastery of STEM and other subjects. “A math teacher can teach about geometric designs in Navajo weaving,” she says. “An English teacher can use a Native American storytelling unit to talk about narratives and story genres.”

Storytelling is at the heart of all of the arts, says Beyal. “Be it music, dance, or weaving. Stories are not just an indigenous art form,” she says. “[They’re] how we all learn.”

“Stories are not just an indigenous art form. [They’re] how we all learn.”

—Brenda Beyal

The arts also foster relationships, growth, and introspection. “You rely on coaches and develop relationships,” Beyal says. “It’s cooperative. You make mistakes and learn from them. And there’s no age barrier—it’s intergenerational.” Art helps students feel connected and valued. She notes, “I had one student with family struggles who wrote in his journal, ‘When I’m doing art, I can forget about everything that’s happening in my life and I feel safe and at peace.’”

Beyal says using the arts can instill confidence in students. “I have my kids start the year doing a difficult, week-long art project, where I stress quality and taking time. I want them to see that through art they could learn behaviors that would help them push through a difficult math problem or writing project. It helps my students set a problem-solving frame of mind they’ll need throughout the year.”

Teachers have struggled teaching Native American content for many reasons. When taught as a social-studies unit, students may see native peoples as relics from the past, not as living communities. Educators can also feel overwhelmed by the astonishing diversity of indigenous peoples, as well as a history rife with broken treaties, genocide, and forced relocations. Finally, bad information, demeaning stereotypes, and concerns about misusing a group’s cultural heritage have made teachers reticent to cover content about indigenous peoples, say Beyal and Flox.

So they had a radical idea. Why not ask Utah’s eight sovereign nations what they would like Utah students to know about them? Surprisingly, it’s a question they’re not often asked. NACI’s resultant lessons and resources—be it using a Goshute dance or a Paiute folktale or a Navajo song—now complement every subject area of teaching.

By teaching the arts in general and Native American arts in particular, says Beyal, “we hope children and teachers will be open to other ways of learning, be more inclusive, and have more empathy and compassion for all people. We can learn from everyone and not walk a narrow path in life.”