A rusty old car transports a father to a mysterious world.

During our son Thomas’s grade-school years, the day finally came when his messy pile of old school papers was too much and a thorough sorting was in order. Sifting through the heartwarming stories and artwork he’d created, I came upon a notebook page with a disturbing image. Was it a black hole? An evil planet? A chaotic nightmare? In black ballpoint ink, he had scrawled over and over a huge circle of countless lines. “It must have been a boring class that day,” I thought.

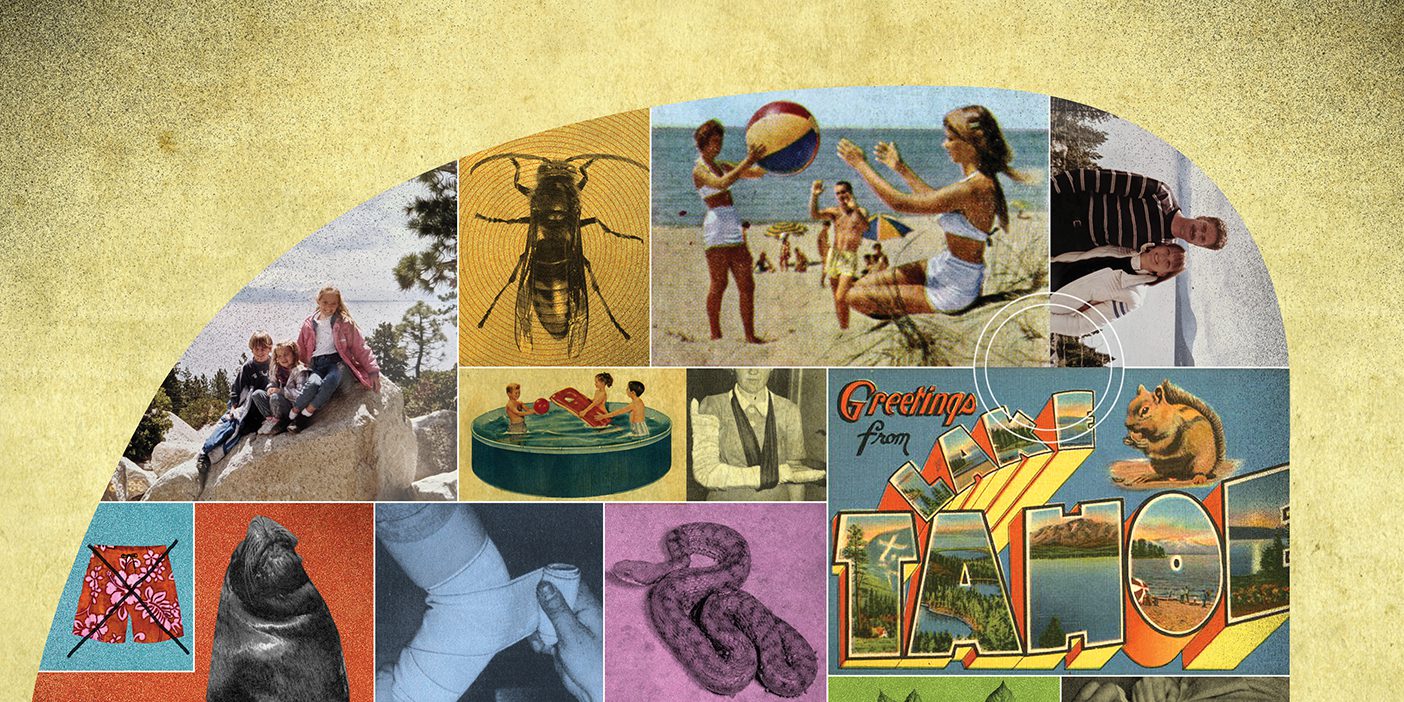

But as I stared longer, it seemed more than idle doodling. To me, the drawing symbolized a perception of the world that I didn’t understand. It was a depiction of Thomas’s world, the planet he lived on—a mysterious, confusing place. It was a place our family had refused to accept, attempted to explain away, cried about, yelled at, and finally tolerated as we tried to understand it—all in the eight years before Thomas was finally diagnosed with ADHD.

The diagnosis and what we learned gave some comfort. It assured us that Thomas’s fixation on cell phones, Pokémon, and mechanical things was common. This was helpful to know, as others had begun to wonder about his obsession with cars. Once, at a family Christmas gift exchange, Thomas refused to open any present unless it could possibly be a toy car. Throughout the years, our living-room floor was a parking lot filled with Hot Wheels. And frequent drag races had remote-control cars zipping through the hallway and down our street.

When Thomas was 13, his obsession grew to life-size—something to be housed in the garage: he wanted to restore a real car.

With plenty of reasons not to do this, I felt secure in the case I made to my wife: “How can we give him a car to rebuild? We don’t have room. I don’t know anything about fixing cars, so I won’t be of any help. He doesn’t even have a driver’s license.”

I told our friend Brother Johnson about the outrageous thing Thomas wanted to do. His reply was unexpected: “Well, what’s stopping you? Take the time you have and work on it together. You won’t have this opportunity again.” Here was an answer so direct and focused—coming from another man’s life and possibly his regrets—that I had to listen.

“Well, what’s stopping you?”

Not much later Thomas found a 1961 Studebaker Lark that we bought, towed home, and, with Brother Johnson’s help, pushed into our garage. The carburetor came in a ziplock bag—disassembled. “How in the world will we get this thing together without a manual?” I complained. With the pieces spread out on the kitchen table and after some effort, I was pleased to discover that two of them actually fit together. With little effort, but with much rejoicing that he did it when I couldn’t, Thomas quickly assembled the rest. As I looked on in awe, I felt as if Thomas’s dark planet could support life—and he seemed to like living there.

Thomas loved the Studebaker, but leaking gas, a loose battery, and other problems meant he couldn’t drive it to school. So he acquired a Volvo, which he repaired, registered, drove, damaged, and repaired some more— then put up for sale. Interested parties appeared. They asked some questions—but not many; they didn’t have the chance. Thomas was intent on informing them of every detail, good and bad—things he fixed, things that were wrong, things that might possibly go wrong.

“It’s great that you’re so honest about the car,” we told him, “but do you have to volunteer every single thing?” Apparently he did. I couldn’t stay and watch his prospective customers run for the hills, so I went back into the house. Minutes later, the door opened and Thomas shouted, “Hey Dad, where’s the title? They want to buy it.”

Through no conscious effort of my own, I had finally landed on that forbidding planet. Looking around, I could only marvel at how strange and wonderful it all was.