A team of BYU researchers uncovers the unimaginable suffering and miraculous faith of the German Latter-day Saints in the midst of war.

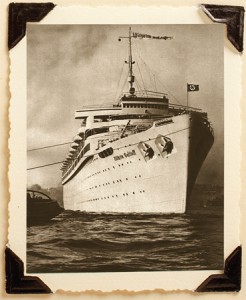

On the night of Jan. 30, 1945, Latter-day Saints Margarete Hellwig and her daughter Gudrun fought their way through the crowds that thronged the piers of the Baltic Sea port and secured passage on the Wilhelm Gustloff. Along with thousands of other German women and children, they had fled their home in East Prussia, leaving husbands and sons to hold off the Soviet army as it advanced relentlessly toward the heart of Germany. Originally designed as a hospital ship, the Wilhelm Gustloff had been converted into a rescue transport vessel to carry the Germans on the Eastern front across the Baltic Sea to Germany and safety. The ship was meant to carry fewer than 2,000 passengers. On the night Margarete and Gudrun boarded, the vessel groaned under the weight of more than 10,000.

On the night of Jan. 30, 1945, Latter-day Saints Margarete Hellwig and her daughter Gudrun fought their way through the crowds that thronged the piers of the Baltic Sea port and secured passage on the Wilhelm Gustloff. Along with thousands of other German women and children, they had fled their home in East Prussia, leaving husbands and sons to hold off the Soviet army as it advanced relentlessly toward the heart of Germany. Originally designed as a hospital ship, the Wilhelm Gustloff had been converted into a rescue transport vessel to carry the Germans on the Eastern front across the Baltic Sea to Germany and safety. The ship was meant to carry fewer than 2,000 passengers. On the night Margarete and Gudrun boarded, the vessel groaned under the weight of more than 10,000.

The Hellwigs were lucky to have made it aboard the ship, and their good fortune continued—they found a place to sit next to the warm engine room, deep within the ship. Just as they settled in, a loudspeaker announced that the ship was overloaded and that the crew was looking for volunteers to disembark before they set sail. At that moment, Margarete received a clear impression from the Holy Ghost. She recalled:

It seemed as if somebody wanted to push me out. I told my daughter, “I’m not staying in here, I’ve got to get out!” She answered, “Mommy, it’s so warm, let’s stay here!” “No, I’m not staying here, I have to get out!” I was so very frightened.

Margarete followed her impression, and the two found themselves once again on shore. They located a smaller ship that was departing at the same time and were soon at sea.

At about 9 p.m. the Wilhelm Gustloff was struck by Soviet torpedoes, and from the deck of her ship, Margarete watched it sink into the Baltic. In what is still the most deadly maritime disaster in history, approximately 9,000 people lost their lives. Had she ignored the prompting to get off the ship, Margarete and her daughter would have been among them. Mother and daughter arrived safely in Berlin, where they were taken in by Church members. Both survived the war.

Just a few years ago, if you were looking for the Hellwigs’ story or hundreds of others like it that chronicle the lives of the Saints in Germany during World War II, you couldn’t have found them in any collection at the Church History Library in Salt Lake City or in the Special Collections at BYU. They weren’t in the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., or at the Bundesarchiv, the German national archive in Koblenz. They could be found only in attics and basements—and in the minds of the eyewitnesses and their families—scattered across Germany and the United States.

Now, however, family history associate professor Roger P. Minert (BA ’77) and a team of student researchers are working to preserve and publish these stories before they fade away. After years of conducting hundreds of interviews and gathering mountains of primary sources, Minert published In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II, a 545-page book following the stories of all 79 branches and groups in the East German Mission. He’s now writing the story of the West German Mission. Together, the volumes will serve as the definitive history of the Church in World War II–era Germany, as told through the eyes of those who lived through the war.

Saints in Nazi Germany

Renate Berger is one of those eyewitnesses. She tells the story of a miraculous experience she had while sitting in Relief Society one day in Berlin. It wasn’t the lesson or a comment by a class member that made the day memorable. It was what happened next door. Her journal entry for Tuesday, May 1, 1945, records:

We had Relief Society in the afternoon. Marie Ranglack gave the lesson. . . . It was very peaceful when all of a sudden a bomb exploded in the building next to ours. The air pressure was so strong that we were thrown off our chairs. Shell fragments came flying through the windows. It was a miracle that no one was hurt. It took our breath away.

Like Berger’s experience, many of the stories told by Minert and his team depict ordinary Saints trying hard to continue living gospel-centered lives amid the chaos of war. And like Berger’s story, they often show that the hand of the Lord was not far away.

By the 1930s, Germany had the largest Latter-day Saint population outside the United States. Although there were no German stakes in 1939, Germany had two missions, 144 branches organized in 26 districts, and a total of 13,402 members.

Although they may have been uneasy about the rise to power of the Nazi party, Church members benefitted from the dramatic increase in employment and prosperity in the 1930s as Germany rose from the ashes of World War I. But that prosperity came at a price—preparations for war played a key role in the economic recovery. In violation of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany began rebuilding its military infrastructure in 1935. Compulsory military service was instituted that same year, and Germany began its campaign of annexation and bloodless conquest in eastern Europe.

The Church temporarily pulled American missionaries out of the country in September 1938, and when war began to look imminent, President Heber J. Grant ordered the permanent evacuation of all Americans on Aug. 25, 1939. From then on it was up to the Germans themselves—in large measure a remarkable group of women, since the men went to war—to keep the Church intact and running.

The story of the Latter-day Saints in WWII Germany is the story of holding on to faith in the face of extreme hardship, as the government demanded unswerving loyalty to the national cause, as food rationing went into place, through the “Night of Broken Glass” and increasing persecution of the Jews, as military orders drafted the young and old alike, through the countless terror-filled nights of air raids, and finally, through the nightmare of Allied occupation, accompanied by starvation, uncertainty, murder, and sexual assault.

Despite the horrors of war, including the complete destruction of the East German Mission office, the Church as an institution survived and remained functional throughout the war. More important, gospel truths were carried in the hearts of the people and sustained them in the difficult times. That is the central question of the project, says Minert: “Can these people weather these storms and still say yes to the Church, to Christ, to priesthood, to charity?”

In Nazi Germany, living as a Latter-day Saint was often a careful balancing act between being a good Christian and protecting one’s self and family.

Hedwig Biereichel, a young LDS mother in Danzig, saw that the Russian prisoners assigned to trash collection were starving. So every week she hid food for them in her trash can and even gave them packages of food when they came by. She reported, “I did enough things in contradiction to Hitler’s instructions that they should have shot me fifty times” (In Harm’s Way, p. 209).

In Chemnitz, Elsa Süss was accused of making treasonous comments, including complaining that the government’s rationing did not provide enough milk for her three young children. Her children were taken and sent to an orphanage, and Süss was eventually sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, where she died in 1945.

Some Latter-day Saints found ways to hold true to their ideals while still demonstrating their patriotism. Rather than joining the Nazi party, one brother joined an organization that celebrated German heritage. A teenaged Church member resisted joining the Hitler Youth, and when this caused problems at school, she volunteered with the Society for Germans in Foreign Nations, aiding German refugees who fled eastern Europe.

No German Saints are known to have participated in the atrocities of the Holocaust, and, writes Minert, “[most Church members]—as most Germans of the day—had no idea what terrible treatment awaited those Jews under the secret German program termed the ‘Final Solution of the Jewish Question’ (the murder of European Jews)” (In Harm’s Way, p. 7).

BYU student Zachary D. Alleman (BS ’10), who has helped Minert with the project, says these stories have taught him not to judge. “As you hear the experiences, you’re able to imagine what they must be going through. It taught me respect for people’s experiences and feelings—you may have your own opinions of people, but we weren’t there, and we have to honor and respect those who lived through it.”

Making History Personal

Roger Minert may have a house and a family on a quiet street in 21st-century Provo, Utah, but he lives much of his life in 1940s Germany. After he served a mission to Germany from 1971 to 1973, Minert went to BYU to study German. As an undergraduate research assistant, Minert scoured issues of Der Stern and other Church periodicals of the time, searching for names of Latter-day Saints who died during World War II. As he did so, he began to wonder how many deaths weren’t recorded, and even more, he wondered who these people were. He began to feel that he was supposed to find their stories and share them with others.

While a few mementos-medals, coins, documents–have made their way into researcher Roger Minert’s hands, he believes the stories he and his students have uncovered are the real treasures.

After pursuing graduate degrees from Ohio State University, Minert worked as a German language teacher and translator and as a family history researcher. In 2002 his family history expertise led to an offer from BYU to teach family history. Three years later he received initial funding to compile a history of the German Church members during World War II, and he began assembling a team of student researchers. Nearly 35 years after he began thinking about the names of the deceased recorded in Der Stern, Minert was finally going to tell their stories.

Since then, Minert and his student assistants have conducted 470 interviews, which Minert estimates as 90 percent of the eyewitnesses who were alive when the project began. Several people Minert interviewed have since passed away, and had he waited much longer to start the project, there may not have been enough eyewitnesses left to piece together the story.

Branch outings (top) Primary on Wednesdays (left), and visits from mission leaders (right) became more difficult as the war progressed in Germany, but many Saints kept their faith through the trials.

Several times a year, students have the opportunity to present their findings at firesides for wards, care centers, and other groups. Sometimes they get to share the podium with the eyewitnesses whose stories they tell. It’s those stories that really energize the student researchers, Minert says. “They’ve been very moved by interviews and enlightened by the amazing loyalty and faithfulness of members. Every one of them has a favorite story.”

It’s more difficult to pin Minert down on his favorite, because so many have left an impression on him over the years. One he does like to tell is the story of Horst Schwermer. During the German retreat before the Red Army, Schwermer went to the front lines to relay a message to a tank squadron. While delivering the message, he was struck by enemy tank artillery, severing his left leg at the knee. The retreating army left him for dead, and he was eventually captured by Russian forces. He was placed last in line to receive medical treatment, and by the time his turn for surgery came up, the supply of ether was all but depleted. He was awake before the operation was completed. Gangrene later developed in the wound, and he underwent further amputation, this one to the hip.

When his wife, Helga, learned that he was alive and only 100 miles from where she was staying in Berlin, she resolved to make the dangerous trip through enemy-occupied territory. When she arrived at the camp, she bribed the guards with food and cigarettes. Helga was given a nurse’s uniform, and she managed to slip into the camp and reunite with her husband, who was hardly recognizable after shrinking from 180 to 96 pounds. “He was only skin and bones,” she recalls.

Horst’s ragged condition may have saved his life. When the Russian army began transporting prisoners to the Soviet Union, the medical staff determined that Horst would not survive the trip and released him instead. For the trip home, Horst says, “on one of the sticks [crutches], I had tied a piece of bread, and on the other end I had tied my triple combination.” Upon seeing his home again, he could hold back his emotions no longer. “I cried and cried.”

In their work to tell stories like Schwermer’s, Minert says his student assistants have been a key to success. Minert has employed 22 students, who serve as general and family history researchers, computer specialists, archivists, transcribers, editors, demographers, and cartographers. “If I had done it myself,” Minert estimates, “I would have needed 10 years instead of three.” Minert even relies on his assistants for the most important tasks, including finding eyewitnesses, conducting interviews, and translating those in German to English.

For Alleman, the mentoring experience has been a highlight of his BYU experience. “When I took history classes before, history was just something I was disconnected from, a thing of the past. Now it’s personal.” Alleman suspects that the source of the students’ enthusiasm is their mentor. “Minert wanted us to experience the history, to learn and grow from it,” he says.

Jennifer A. Heckmann (BS ’09) used her native German and fluent English to conduct more than 50 interviews over the phone and in person. She even conducted interviews during visits home to Germany. Hearing others share their experiences of suffering and faith, she says, helps her put her own trials in perspective. “Sometimes when I interviewed, I would sit back and listen to these stories and think, ‘You know, that exam I have to take tomorrow is not that big of a deal.’”

Heckmann recalls a story from her interview of Horst Schäler, who lived with his family in Forst, on the German-Polish border. Though only a child when Russian forces reached Forst, Schäler remembered the scarcity of food and how the adults in the branch prayed for a miracle. They received one when Russian artillery destroyed a military supply depot, and German soldiers brought the soon-to-be-spoiled food to the Schäler apartment.

Even more memorable for Heckmann is the story of the children’s faith. She recalls from the interview: “A couple days later, the kids in the branch were together and said, ‘Well if that worked . . . I haven’t had chocolate in such a long time.’” So they prayed for chocolate, not telling the adults about their prayer. “One day, Horst’s older brother Hans, who was a soldier, passed a bombed-out grocery store, and it was completely destroyed—except for this little display of chocolate.” He presented the chocolate to his little brother and his friends a few days later, unwittingly helping the Lord answer the prayer of a group of Primary children caught in the firestorm of a world war. What does Heckmann learn from stories like this? “No matter what comes, we can make it through with Heavenly Father’s help.”

When bombs began to fall on the east German city of Chemnitz, Bruno and Joanna Fischer took cover in their basement, along with six others. Tragically, all were killed by a direct hit.

“The Testimony Kept Me”

On March 5, 1945, the city of Chemnitz was hit by a series of devastating air raids. According to Latter-day Saint Herbert Heidler, the scene was horrific: “They dropped phosphorus and people burned alive. They ran to the next pond trying to extinguish the fire but when they came out they were burning again just seconds later. They stayed in the water until somebody helped them to scrape the phosphorus off their skin.”

From her home in Neuwürschnitz, 12 miles to the southwest of Chemnitz, Hildegard Göckeritz watched the red sky to the northeast with dread. She had grown up in Chemnitz, and her parents, Bruno and Johanna Fischer, still lived there. At the time of the air raids, Hildegard’s two sisters, Elisabeth and Erika, along with Erika’s two young sons, were visiting her parents in Chemnitz.

In the days following the raids, survivors poured into Neuwürschnitz, clothes in tatters and hair and skin scorched. The Fischers were not among them. Hildegard recorded the next days in her journal.

Saturday, March 10, 1945

I still have no word from Chemnitz since the terrible attack on March 5. . . . If I didn’t have the Church right now . . .

Wednesday, March 15, 1945

A sad day for me. Rudolf was here and brought the bad news from Chemnitz. My loved ones are all dead. Oh, I just can’t believe that they’re all gone. My dear parents, my dear sisters Elisabeth and Erika, and her two little boys. Can it really be true? I dare not even think about it.

Thursday, March 16, 1945

Today I was in my hometown, Chemnitz. The picture of destruction. I stood devastated before the house in which I was born. Mrs. Otto went with me. I am really scared to even be in this city. Oh, what terrible suffering this war has brought upon mankind.

In addition to the six members of the Fischer family, two elderly sisters had sought refuge in the same apartment building’s bomb shelter. All eight were killed instantly by a direct hit. According to Minert, “It may have been the single worst tragedy in the Church in Germany in World War II.”

For student interviewers like Heckmann, it is almost incomprehensible how people like Hildegard Göckeritz endured such loss. How did they remain true to the gospel and trust in God in times like those? She says that is the project’s purpose, “to see how much they suffered and how they still trusted in the Lord.”

At the end of interviews, Heckmann always asks, “How did you keep a testimony during all these trials?” In response, she says, the eyewitnesses tell her, “I didn’t keep a testimony through those times—the testimony kept me.”

Alleman has learned a similar lesson. “Although they were pushed beyond their limits, they kept their testimonies. They weren’t shaken. They talk about how strengthened they were by the experience. What a lesson for us—we can have the worst experience, but there’s always the presence of God nearby.”

Nathan Waite is an editor on the Joseph Smith Papers Project.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.