Illuminating Texts

While the ancient, weathered Bibles in BYU’s Special Collections bespeak the record’s antiquity, for the careful reader the scripture yet yields fresh insights and newness of life.

By Steven C. Walker (BS ’65, MA ’66) in the Fall 2014 Issue

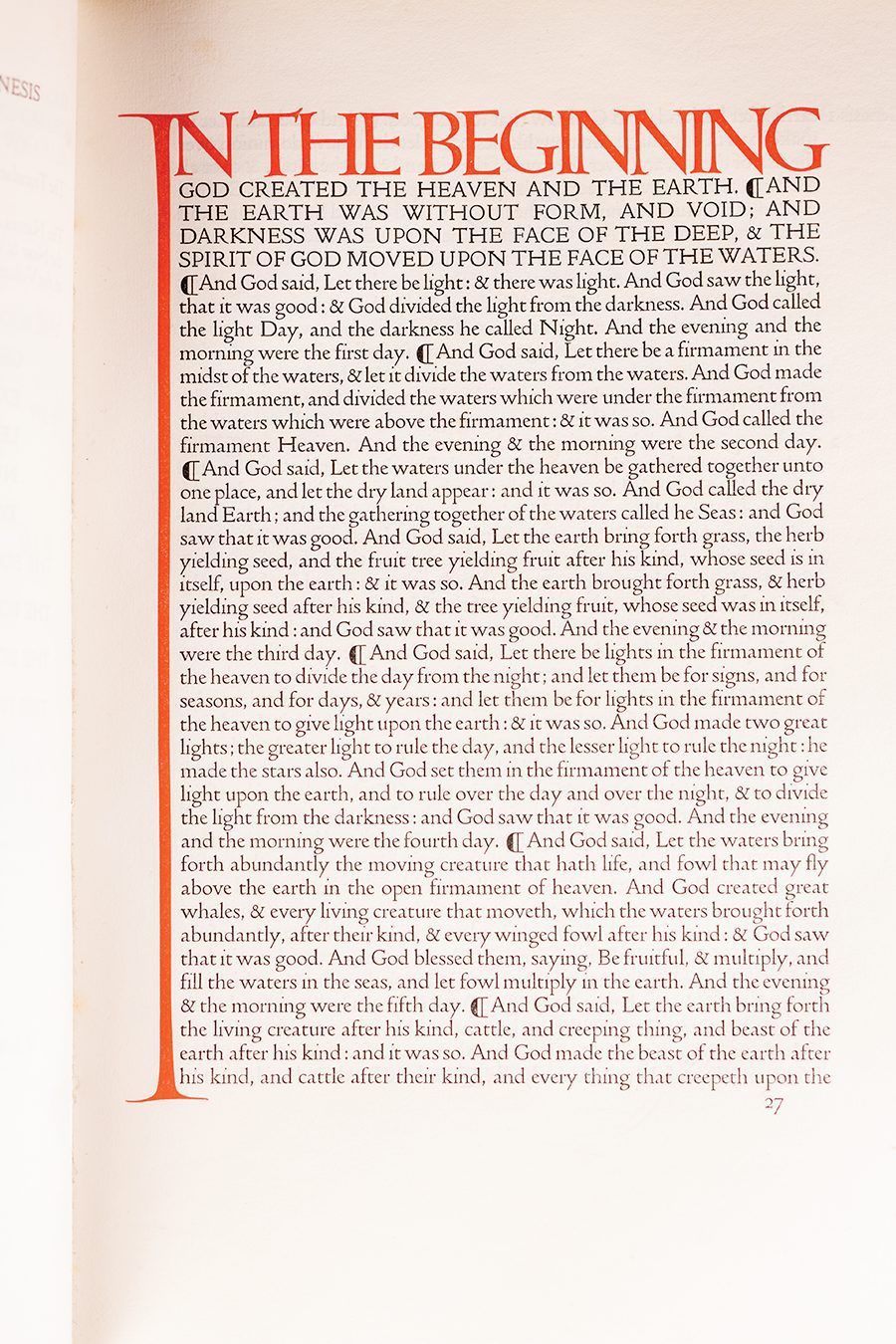

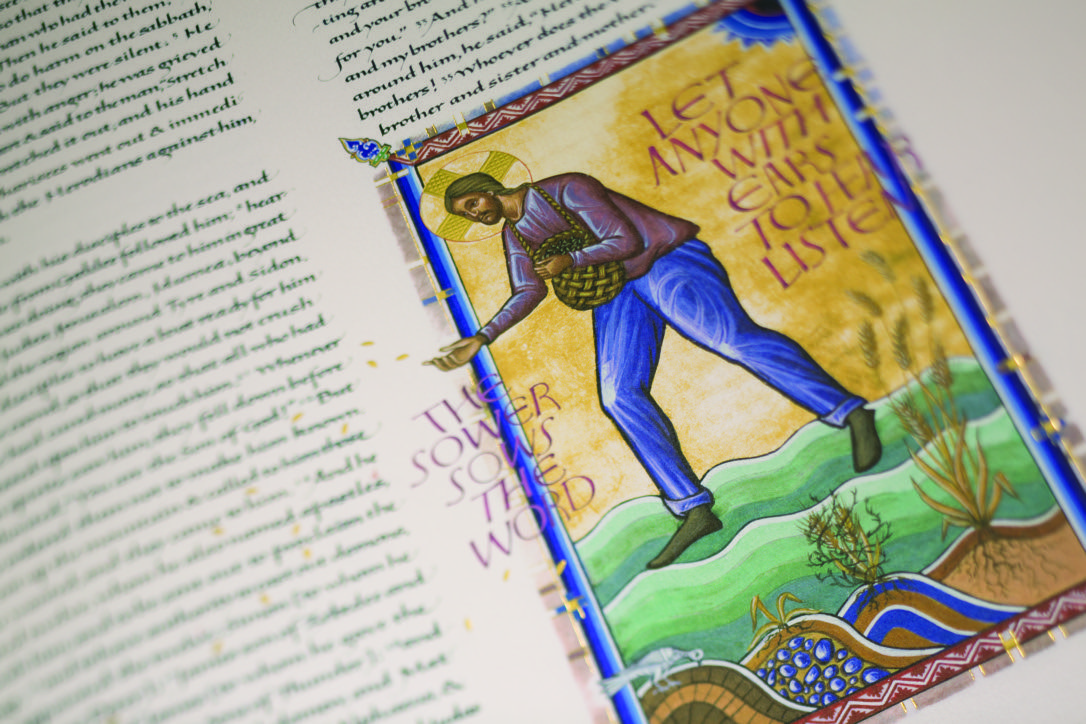

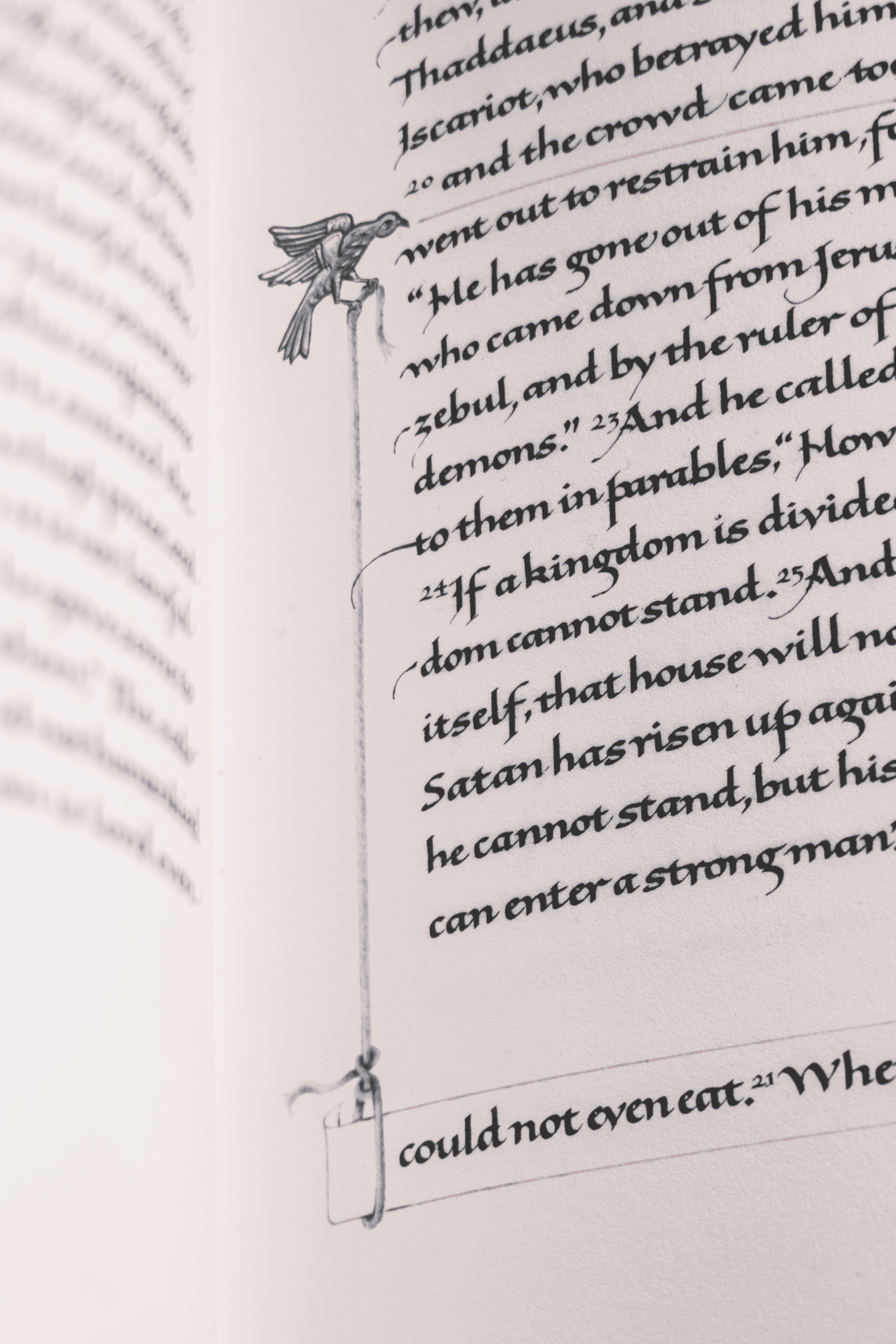

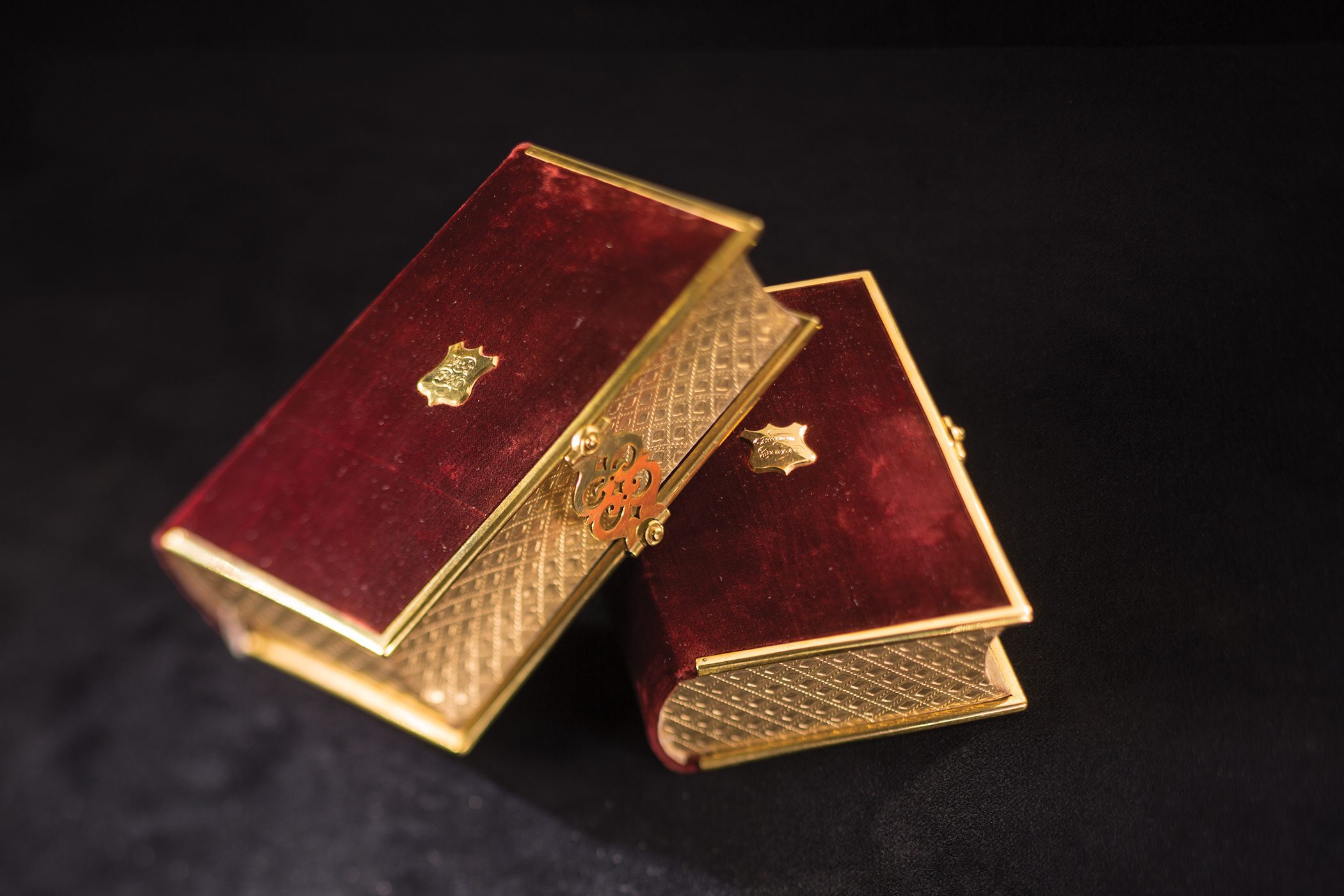

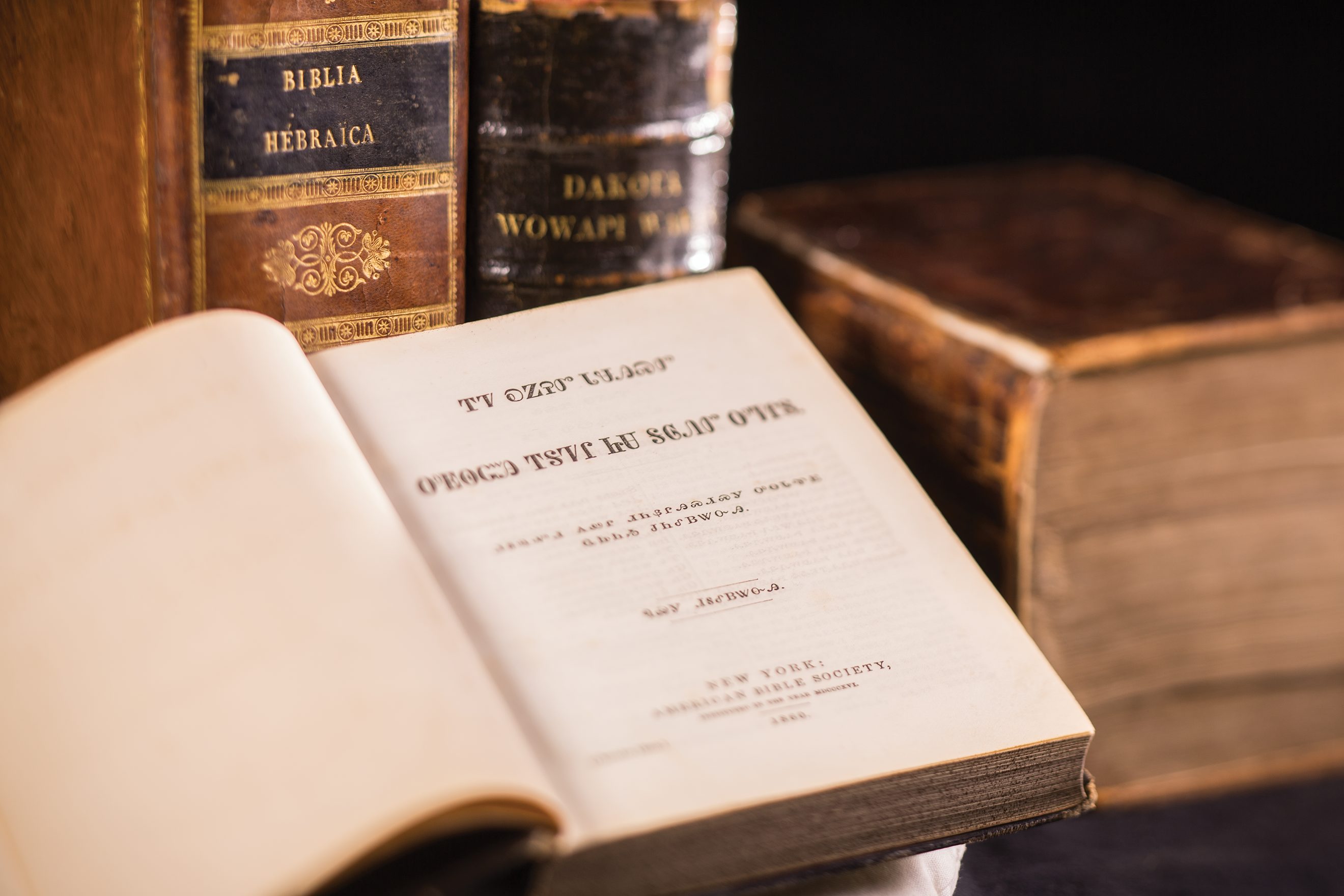

The rare Bibles in the BYU library’s L. Tom Perry Special Collections cover the spectrum—from 12th-century manuscripts to a facsimile of the massive Saint John’s Bible, a modern transcription completed in 2011. The collection’s hundreds of Bibles include illuminated texts, a leaf from the Gutenberg Bible, and volumes in dozens of languages (including Navajo, Hawaiian, and Arabic). Add the scores of circulating copies, and the Bible is easily the library’s most widely held work. And yet, despite that fondness and fascination for the familiar Good Word, retired English professor Steven Walker argues here that the Bible holds undiscovered worlds for readers willing to venture beyond what they already know.

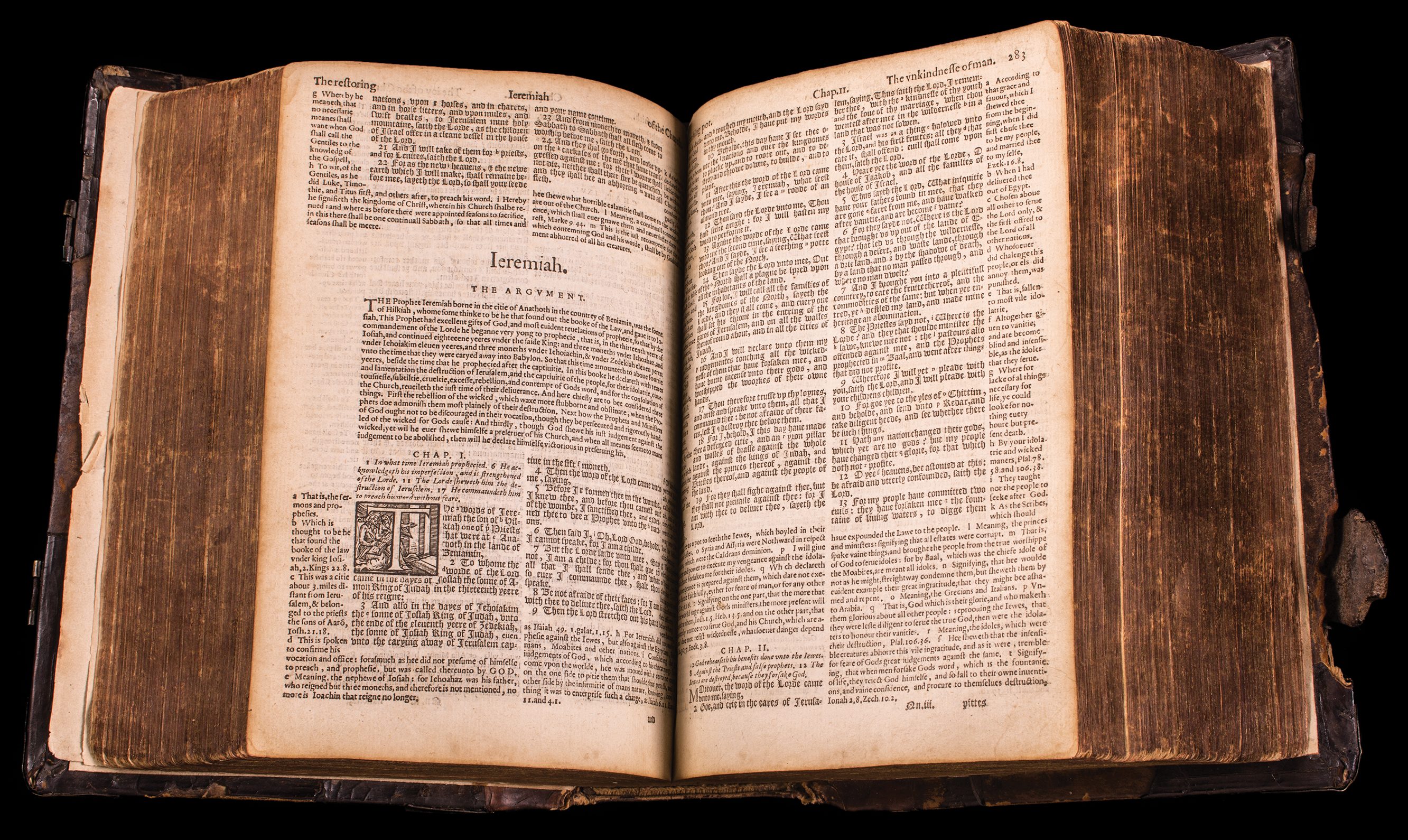

With its original leather binding and worn page edges, this 1594 Geneva Bible represents the first English translation to include verse num-bers, chapter headings, and marginal glosses and cross-references. Considered the first English study Bible, it was translated by Protestant scholars who had fled to Europe during the reign of Queen Mary in the mid-1550s. With forceful language, borrow-ing heavily from previous translations by William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale, the Geneva Bible soon overtook England’s authorized Bible in popularity. “If you had a Bible, this is the one you would be read-ing at home, even though there was a government-authorized translation that you would be getting at church,” says Melissa “Maggie” Gallup Kopp (BA’98), curator of European books at BYU’s L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

The Bible is the best-selling book of all time—estimates run as high as 6 billion worldwide, one for almost every person alive. Yet it’s a rare Bible owner who picks it up often enough to pick up much of what’s in it. Sixty percent of Americans “say they read the Bible at least on occasion,”1 but fewer than half can name the first book. Only a third know who delivered the Sermon on the Mount, many guessing Billy Graham. Fully a quarter of American Bible readers do not know what it is that Easter celebrates.2

Latter-day Saints are more likely to read the Bible with their eyes open. In an experiment in one of my Bible as Literature courses, BYU students averaged 87 percent on the final exam for the equivalent course at Yale—on our first day of class. We are “people of the book” at a more involved level than many other Christians or Jews. Our Bible problem is more of a first-world problem—good as our reading is, it might be keeping us from reading better. We know well what we know of the Bible, but we don’t know the half of it.

“The Bible is meant to push mental parameters, stretch emotional envelopes, expand the soul.”

For 50 years I’ve been struggling to really read the Bible, to read it as intently as if it were one of the “best books” (D&C 109:7), the finest literature. It is. The Bible can get richer every time you read it. After a lifetime of reading, my favorite novel remains The Lord of the Rings, but I’d rather read Genesis now—or Judges or Ruth or 2 Samuel or Jonah or Esther or Job or Psalms or Luke or Acts or James, the book that made Joseph Smith realize that the old answers the Bible provides may be less crucial than the new questions it raises.

When we pay those new questions some mind, the book is mind-boggling. The Bible can take old expectations into entirely new places, as it did Joseph’s. It can perform laser eye surgery on perspectives, enabling readers to see the familiar world from fresh frames of reference. Its unexpectednesses can jerk a soul out of religious lethargy, churn up cultural complacency, unsettle settled notions, startle habitual viewpoints into new insights.

And yet, much Bible reading limits itself to reviewing. The Bible can become for us what it what was for Queen Victoria, our “comfort,”3 our defense, our rock—but not so much our road to Damascus or Emmaus or the promised land. The unnerving surprise of the original can be unsettling. But domestication of the Lion of Judea to something more like a house cat, safe as it can make a reader feel, saps the scope and mutes the impact of the Bible.

An old-slippers habit of reading in the same comfortable ways makes the good news of the gospel never really news, never actually new. The miracles become mundane, the prophecies predictable. The parables, which depend upon surprise for their impact and import, are rendered routine. If I don’t bring something creative to my long-term relationship with the Bible, it can lose its zest, the Incarnation itself downsizing from the cosmos-shifting shock of the Gospels—God is right here “with us” (Matt. 1:23)—into something closer to anticlimax—apparently He came around in the past.

As with spouse dating—where however pleasant and however regular and however dedicated, the same old dinner-and-a-movie isn’t likely to revive the marriage—so our Bible-reading relationship can benefit from creative energy and renewed effort. When I read that way, the Bible opens up new vistas everywhere I look. I have found some new ways of looking especially revitalizing:

Try a little risk in your Bible reading.

Readers commonly go to scripture to reaffirm faith, to refocus theology, to retrench traditional values. But the Bible is meant to push mental parameters, stretch emotional envelopes, expand the soul. I discover more of what is actually in the Bible when I read with vulnerability to the possibility of actually having to do something about it, like the aging grandma poring over her Bible, “cramming for finals.” I read deeper when I’m anxiously—or better yet, desperately—engaged. I read stronger not doing laps in the Bible pool confirming what I already know, but struggling up its mountain rivers toward “newness of life” (Rom. 6:4).

Try seeing what’s actually on the pages of the Bible, and not just what you noticed last time through.

Women, for instance, who weren’t even there the first time I looked, now star. The first half-dozen times through, I overlooked a momentous biblical fact: it’s a woman that gets it rolling. Eve turns the ignition key to life and inadvertently floorboards Bible action (see Gen. 3:6), action driven dramatically by her daughters. Every ensuing Genesis scene that features a woman—and almost all do—revs up the real-life motor of biblical narrative: dull boy meets lively girl, girl upsets everything, everything’s better: things go better with girls.4 I get asked why women are so peripheral in the Bible often enough to suspect I may not be the only one whose reading will be enriched by noticing what’s actually in the book.

Try meeting the people of the Bible as people rather than Marvel Comics superheroes.

Approaching this rich array of characters as mere role models disguises the most illuminating aspect of them—Bible folk are anything but Sunday School stereotypes. The short circuit between what we expect from Bible exemplars and what we get can provide shock treatment for reader psyches, or at least a palm buzzer that can stagger us into new realizations whenever we shake hands firmly enough with an actual biblical character.

The pick of the Genesis litter, angelic Joseph, gets so holier-than-thou full of himself that it’s not hard to understand why older brothers have had all they can stand of him (see Gen. 37:18–20). We’re talking real people here, genuine human interest. We can relate—and liken these people unto ourselves (see 1 Ne. 19:23). I would appreciate Joseph even less than his brothers do if the Bible shortchanged us with a sermon, idealizing a do-gooder, leaving out the smug self-righteousness. When Genesis shows what Joseph can become when he gets the memo about not being a jerk about his goodness, who could not love the man? When I don’t airbrush them away, the flawed stumblings of these folk toward magnificence look so distressingly and hopefully like real life that I’m left with no excuse for not identifying.

Try reading for joy rather than out of a sense of duty.

For a book we are disposed to read somberly, the Bible finds a remarkable number of things “happy” (Ps. 144:15), “lovely” (Phil. 4:8), or even funny. Revered Apostle Paul, greatest preacher ever, gets himself kidded for being fond of the sound of his own voice. Paul’s persistent much-speaking throughout Acts frames that delightful scene when he “continued his speech until midnight” (Acts 20:7). “And there sat in a window a certain young man named Eutychus, being fallen into a deep sleep: and as Paul was long preaching, he sunk down with sleep, and fell down from the third loft, and was taken up dead” (vs. 9). A shamefaced apostle interrupts his sermonizing to resurrect the disciple he bored to death. But that’s not sufficient irony for the Bible. A scant two verses after the hard-earned lesson on length of sermon, Acts informs us, tongue firmly in cheek, that our hero, that very night, “talked a long while, even till break of day” (vs.11).

Try soaking in the attitude of the Bible.

I delight in its bracing tone—frank, open, honest—worlds away from the simpleminded and mealy-mouthed preacher piety some manage to think of as the Bible’s voice. The real voice doesn’t talk down to us. Far from a lecture on enlightenment, it enlightens by example, the examples more often negative than not—as in the finest literature, as in life. Samson and Jonah and Elijah and Elisha and his she-bears and Ruth and Esther and Saul and Solomon and my all-time favorite, David, rack the Bible-reading brain in search of simplistic “just don’t do it” morals for those provocative stories. Every page testifies to how blessed we are that the Bible is not a sermon but a stimulating conversation.

Try pursuing the questions.

Grateful as I am for whatever biblical answers I glean, I find my Bible reading more energized by its questions, probably the most profound ever posed: “Am I my brother’s keeper?” (Gen. 4:9); “Doth Job fear God for naught?” (Job 1:9); “Have the gates of death been opened unto thee?” (Job 38:17); “What is man, that thou art mindful of him?” (Ps. 8:4); “Is there no balm in Gilead? Is there no physician there?” (Jer. 8:22); “And who is my neighbor?” (Luke 10:29); “Lord, is it I?” (Matt. 26:22).

Try making the most of the Bible’s open-ended invitations to change.

The best new way to read for me, the biggest breath of fresh air stirs in the Bible’s breathtaking new ideas. The “mighty rushing wind” (Acts 2:2) of the Bible’s soul-stretching insights “bloweth where it listeth” (John 3:8), even into the places we know best in the Bible, like Jesus’s parables—those simple little tales told to make a point, a point we thought we got long since. But even as we get the point anew, we realize the essential point is that there’s more point to get. Yes, the upside of being a prodigal is that you can be forgiven. Yes, the downside of being righteous is that you need to learn to forgive. And yes, yes, yes, what if we were to stretch our souls far enough to see life from the perspective of that absurdly indulgent father?

It’s heady stuff when it’s rethought rather than merely reviewed. That newness—that fresh meaning we tend to miss in our Bible reading because we already know what’s there—says, bottom line, that we limit ourselves when we limit our vision, when we confine our souls to ruts of inertia or constraints of creaky catechisms. The message of the portion of the Bible we’ve sealed from ourselves is this: there’s more. Yet to be revealed to us through the Bible are “many great and important things” (A of F 1:9). Continuous revelation doesn’t just mean we can get more scripture. It means we can continue to get more out of the scripture we have.

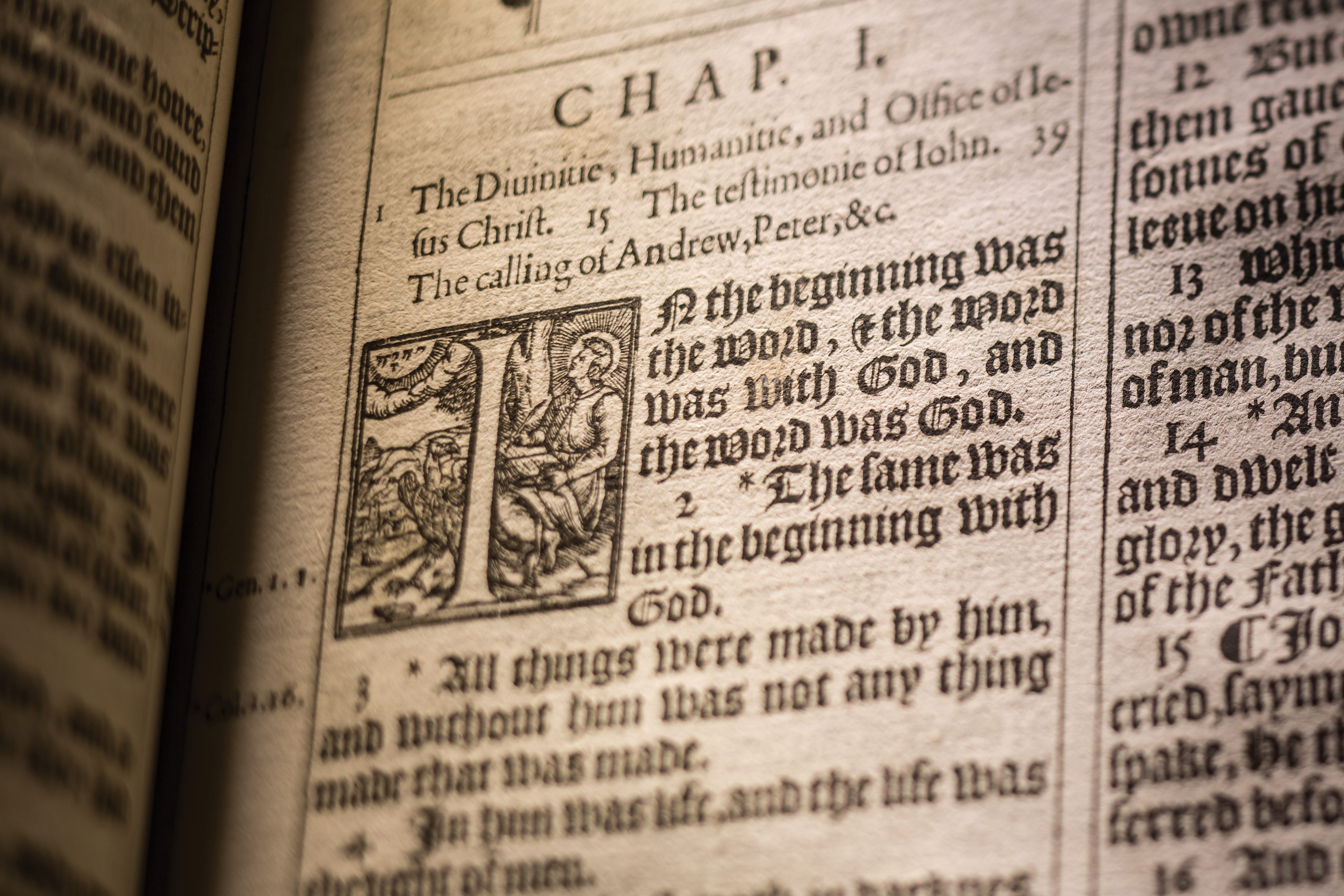

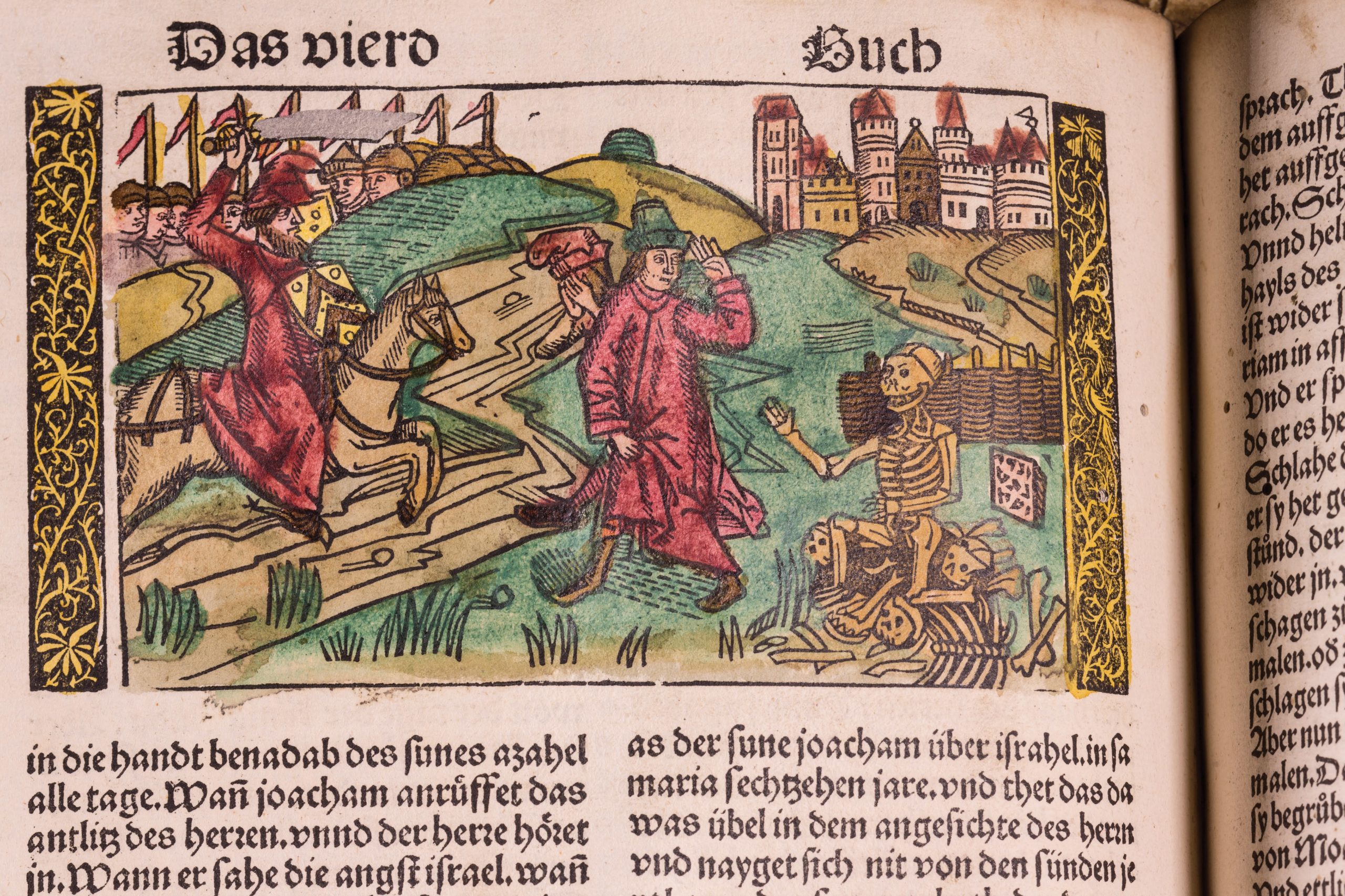

Hand-decorated woodblock illustrations add color to this 1507 German Bible (above), the library’s oldest Bible translated into a modern European language (preceding Martin Luther’s translation). With Luther’s reforms and the rise of Protestantism, Bible translations would proliferate as missionary-minded organizations took the texts all over the world. Examples of the linguistic diversity in BYU’s collection include Bibles in Cherokee, Hebrew, Dakota, and Hawaiian.

Steven Walker retired in 2013 after teaching the Bible as Literature and other English courses at BYU for 47 years.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

NOTES

- Alec Gallup and Wendy Simmons, “Six in Ten Americans Read the Bible at Least Occasionally,” Gallup, Oct. 20, 2000.

- “A Bible in the Hand Still May Not Be Read,” Baptist Standard, Dec. 4 2000.

- James Eli Adams, A History of Victorian Literature (Oxford: Wily-Blackwell, 2012), p. 137.

- Steven C. Walker, Illuminating Humor of the Bible (Eugene, Ore.: Cascade, 2013), p. 90.