A BYU graduate has dedicated himself to the belief that everyone was born to smile.

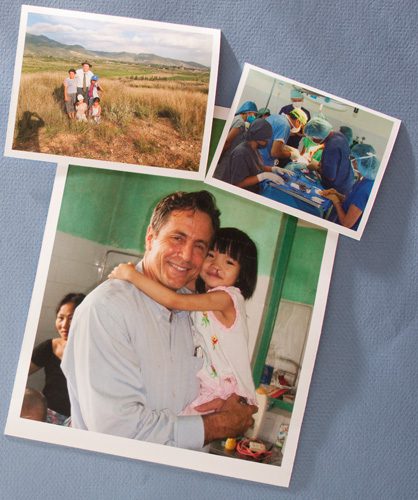

Only home for a few short visits each year, Geoff Williams travels around the developing world performing reconstructive plastic surgeries on children with cleft palates and other deformities.

As they entered a crowded gymnasium in South Vietnam, W. Geoff Williams (BS ’80) and his travel companions were overwhelmed by 200 women and their deformed children. The visitors were doctors from Taiwan, come to perform free surgeries on children with cleft lips and palates.

Assuming Williams was the expert because of his Caucasian complexion, frantic mothers pushed him against the gymnasium door, holding their babies close to his face. But Williams was the novice in the group, an American plastic surgeon joining a team of experienced Taiwanese doctors in a desire to learn from them.

The medical team stayed in Vietnam for just a few days, working long hours as they performed surgeries the children desperately needed. They were only able to treat about 20 or 30 of the patients—the other 170 to 180 had to be turned away.

Williams came to Southeast Asia looking for practical medical experience. What he got was a life- and career-altering experience. “I remember thinking about all the people we had helped as well as the people we had to turn away,” he says. “I decided I would really like to spend my time in the developing world and devote my time to taking care of these kinds of kids.”

Devoted to the Work

Williams, however, did not have the money to make that commitment. So he returned to Galveston, Texas, and worked as a plastic surgeon, steadily saving his earnings. It took five years, but in 2003 Williams left a successful private practice and a medical-school teaching position to dedicate himself full-time to helping children with deformities around the world.

Initially Williams joined medical missions planned by other organizations. When his personal finances were depleted, he did not stop. Instead of returning to private practice to generate income, in 2005 he created the International Children’s Surgical Foundation (ICSF). Completely run by volunteers, the nonprofit organization funds surgeries for hundreds of children each year, motivated by its motto: Everyone was born to smile.

Traveling for three weeks to a month at a time in developing countries, Williams and the medical personnel who join him treat cleft lips and palates as well as other deformities. During one year, they visited the Philippines, Mexico, Bolivia, Vietnam, Thailand, Pakistan, China, Peru, and Kenya. Most years Williams averages 16 trips to eight countries.

Without a home or family of his own, Williams stays with his parents in Boise, Idaho, when he returns to the United States for brief stops between trips. “Geoff is only home four or five times a year,” says his mother, Bev Williams. “And when he does come home, he’s catching up on loose ends. He does all his own scheduling too, which to me is a minor miracle. While he’s in Mexico he sets up his schedule for Pakistan or whatever country he will visit next.”

Kevin Kartchner, an anesthesiologist who has accompanied Williams on trips to the Philippines, says he does not know how his friend holds up, but he can tell Williams thrives on it.

“He lives to do this work,” says Bev. “He is completely happy and feels as if he is doing what he was born to do. This life just unfolded for him.”

Making a Difference

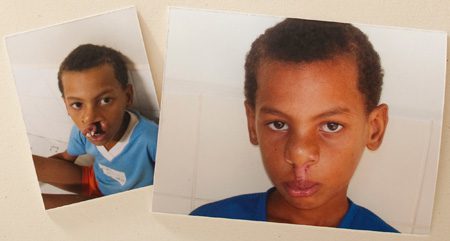

After a failed attempt by a humanitarian surgical team to correct Francisco’s cleft palate, his mother decided she would keep him from attending school to protect him from ridicule. Seven years later she learned that Williams’ organization would be visiting the area and she decided to try again. Williams and his team took time to perform the operation carefully and provided follow-up care after surgery. When they removed the stitches a week later, Francisco saw himself in a mirror and said, “Now I want to go to school.”

“Cleft lips are pretty ugly deformities,” Williams says. “I could see if you had to look at that every day when you look in the mirror, it would be a hard thing to try to be a member of society. Once I was able to do a cleft-lip repair on a Bolivian girl who had been suffering for 21 years; within a year after the surgery she got married.”

Cleft lips and cleft palates are birth defects in which the lip or the roof of the mouth (or both) does not form properly, leaving a gap. In the case of cleft palates, the gap connects the mouth and the nasal cavity.

Through donated supplies and labor, surgeries to repair these deformities cost the ICSF only $250. And Williams’ vision for this work involves more than just quick fixes. Many medical missions of this type last only a few days. Williams often plans his trips to last a few weeks, allowing his medical team to spend more time on the surgeries, to treat more children, and to provide post-surgical follow-up care.

The effort, says Williams, is worth it.

Conchita was a young Mexican girl with severe burn deformities caused by a house fire that killed her mother. When examining Conchita’s badly scarred face, Williams saw one thing he could fix. Her nose had been scarred down to her upper lip, causing severe distortion. Assessing the tissues, he began to gently pinch Conchita’s nose. The small child responded by reaching up and pinching his nose as if to say, “If you can do that to me, I can do it back to you.”

Conchita’s surgery proved to be more challenging than anticipated and required nearly four hours of concentrated work. Williams, however, was able to give the little girl a nose and an upper lip.

On a later trip to the region, Williams checked on Conchita. Her grandmother and her family invited him to stay with them, and now they even have a room reserved for him in their small home. Through their close relationship with Williams, the family became interested in and joined the Church. Now one of the sons is serving a mission in Mexico.

Sharing the Vision

At the end of one of Williams’ early trips, a local doctor asked Williams to return to train her and her colleagues to perform safe, high-quality surgeries on their own. Inspired by the request, Williams began teaching doctors all over the world. ICSF plans longer trips in part to allow time to conduct the necessary training.

“Helping train the local doctors has been really rewarding,” Williams says. “I know that I can’t reach everybody in the world, but if I can teach doctors in various countries and they teach their own students, then it’s kind of a logarithmic increase of my efforts.”

Already three doctors in developing countries who were trained by Williams have opened their own clinics and have begun treating children for free. This ripple effect adds significantly to the 1,500-plus surgeries Williams has performed in more than 12 countries.

Serving children and families in developing countries has brought into focus for Williams the disparities in quality of life throughout the world; he works almost daily with children who have lived with deformities that in the United States would have been repaired soon after birth. His work has also shown him the reward that comes from working to improve the life of a child.

“Sometimes I get tired and feel as if I can’t go on,” he admits. “But then I remember I still have patients waiting for treatments in various places of the world. So I just say, ‘Well, I’ll just keep doing it.’ It’s an overwhelming life to do this, but I don’t think I could ever really stop.”

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.