Asking his stepfather about the war led an alum to publish a book and redeem a relationship.

In March 1944 Frank Kirkland was a copilot in a U.S. Army Air Corps B-17 bomber squadron, its target a German railroad yard in Padua, Italy. The squadron dropped its bombs but was soon intercepted and shot up by German fighter pilots above occupied Yugoslavia. As Kirkland’s burning plane fell to earth, the crew ditched in time to parachute out, but Kirkland badly broke his leg on impact. Rescued by partisans and smuggled to safety, Kirkland had his life, but the crash and his injury shattered his dream of being a fighter pilot, a pain he stored away inside and never forgot.

Although the mission was a success, Kirkland didn’t know that an errant bomb also destroyed a Renaissance-era church and its gorgeous fresco by Andrea Mantegna. For decades some 88,000 pieces of fresco rubble were kept in boxes until, in 2000, a mathematician developed an algorithm to arrange the pieces and help restore parts of the masterpiece.

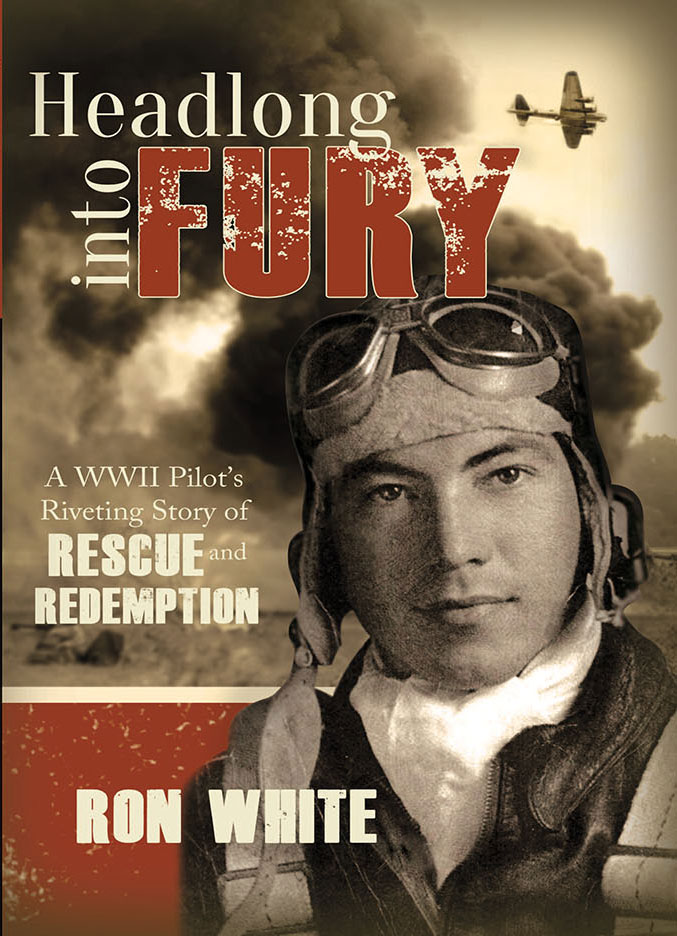

The story of that fresco’s destruction and restoration became a metaphor for attorney Ronald E. White (BA ’81, JD ’84) as he tried to make sense of his tough, enigmatic stepfather, Frank Kirkland. In the process of piecing together Kirkland’s story—which White would later publish with Cedar Fort as Headlong into Fury—he helped restore a strained relationship and came to better understand the man he called Dad, the only father he’d ever really known.

White was part of a his/hers/ours blended family—one with a lot of boys. When White was a toddler, his mother had divorced and remarried Kirkland. “Dad was tough on me, but he was there,” Ron says of their relationship. “He did stuff for me. He was at games. He considered us his sons, but I was afraid of him.” White eventually went to BYU, earned a law degree, and practiced in California. In 2008 his mother died unexpectedly, leaving his aged stepdad to care for White’s brother Jeff, who has Down syndrome. The change set the stage for a thaw in their relationship.

It began with simple phone calls. When White called his stepdad, he says they would talk about “surface stuff . . . like doctor’s appointments.” Grasping for a way to connect, one day White asked, “Hey, Dad, what can you remember about the war?” The question kindled a fire. “Wow! He came alive again in a remarkable way,” says White. “I began to understand how deeply personal that time was for him and how, of all the things that he had done in his life, this was the most important—and the happiest time. That was beautiful for me to see.”

One call became many. Questions spiraled into research, and White gathered fragments of his stepdad’s life, which he brought together into a narrative. He learned how Kirkland had grown up poor in Phoenix, graduating from high school in the shadow of WWII. Kirkland had shown his grit early on by building a car from scratch using junkyard parts. The athletic teen was determined to be a pilot, but he didn’t have two years of college to qualify for flight school. So he became an airplane mechanic—“a good one,” says White. With so many pilots being killed, the Army Air Corps changed its regulations so others could fly, and Kirkland slavishly devoted himself to passing the test to become a pilot. White learned that, for his stepdad, flying was everything, a symbol of rising above his rough upbringing.

This background helped White understand how losing the chance to be a fighter pilot pained Kirkland ever after. “He never bemoaned other disappointments, only that he got yanked from being a fighter pilot,” says White. “He had an innate sadness and disappointment about him. He worked hard, doing two or three jobs, but didn’t enjoy his accomplishments. If he could’ve stayed in those planes and done a little more, he would’ve gladly done that, even if it meant death. Flying was the most meaningful thing he ever did.”

As the calls continued and the notes accumulated, White began to write a book. He took the unusual step of writing in the first person, forcing himself to walk in his stepfather’s footsteps and understand his motivations and aspirations. Much of his stepfather’s experience in life, White came to see, “consisted of little epiphanies along the way, where things didn’t go the way he wanted but, by staying focused and doing his best, he found a way forward. He did that over and over again.”

After White published his book in 2016, he attended a book signing with his stepfather at a Barnes & Noble in Mesa, Arizona—a salve on his father’s wounds. White recalls that “people were lining up to talk to [Kirkland] and thank him for his service. He just kept saying, ‘Ronald, I can’t believe it. These are things that happened 70 years ago. Why are these people here?’ It was a sweet thing to see.”

“Through this book I think that my brothers and I have connected to Dad in a different way. It is his story but also our story. We can understand him better than we did before,” says White, who gave the book the subtitle A WWII Pilot’s Riveting Story of Rescue and Redemption. “The ‘rescue’ part of the title is not so much that he was rescued from behind enemy lines, but in a way this whole process rescued us and redeemed us in our relationships with him. When I told Dad about the destroyed church in Italy and its restoration, he understood the connection that I was trying to make.” That connection was to him.