Meet Mr. Curiosity

Meet Mr. Curiosity

With the mind of an engineer and the humor of a 12-year-old, an alum is making the internet better, one prank at a time.

By Brittany Karford Rogers (BA ’07) in the Summer 2021 Issue

Photography by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

Most people, when a package gets stolen from their porch, will curse their bad luck. Maybe file a report. YouTube star Mark B. Rober (BS ’04)? “Make a revenge bait package and over-engineer the crap out of it.” That bit of engineering brilliance greeted porch pirates with a shower of fine glitter, unsavory scents, and some Home Alone audio: “Keep the change, ya filthy animal.” All this captured on video.

“Is it petty?” asks the former NASA engineer. “And beautiful? Yes.”

The result, “Glitter Bomb 1.0 vs. Porch Pirates,” is now one of the most-watched videos on Rober’s eponymous YouTube channel, with 86 million views. His offerings include science explainers and feats of engineering—things like filling a pool with Jell-O or a hot tub with liquefied sand or creating the world’s largest Nerf gun or an automatic snowball shooter (each demonstrated on his unsuspecting niece and nephews in his videos).

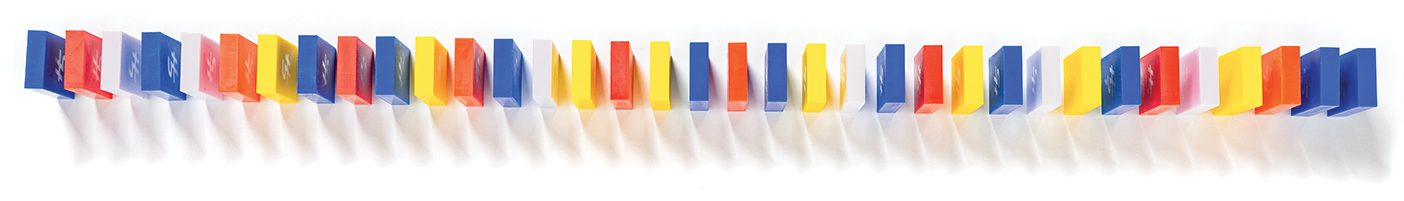

His latest video is his longest YouTube labor of love yet; four years in the making, it rivals the time he spent working on the Mars Curiosity rover at NASA. This one is a robot too—one that can set up a gym-sized domino course overnight.

If past performance is any indicator, it will likely garner more than 10 million views—Rober’s videos haven’t notched anything less in five years. Rober has nearly 19 million subscribers, the YouTube equivalent of converts. Basically, someone is always watching him online.

“The only time it freaked me out,” confesses Rober, was actually at a recent BYU football game. In the three-plus hours he was watching the game, his videos streamed in the homes of 10 times the number of fans around him in LaVell Edwards Stadium. “That’s crazy,” says Rober, but it’s also sort of his new normal. For a time his channel held the YouTube title for the highest average views per video for an individual creator.

The antics are fun and all, but they can make one wonder: couldn’t Rober’s beautiful mind be put to better use solving the problems of the day?

Turns out, it is. Rober has been covertly cracking on cutting-edge tech for Apple, and he’s using his megaphone to be a teacher and an advocate. He’s taken on issues like climate change and deforestation—rallying the internet to plant 20,000,000 trees along the way. And earlier this year, he released a video on the cause dearest to his heart: his son’s autism.

For the most part, though, he just wants to do outrageous builds, sneaking the science in along the way. And in actuality, Rober says, his ridiculous engineering stunts may be his most important work.

Immaturity at Its Finest

“Plug in, Mark!” It’s the refrain Rober heard all the time growing up in Brea, California.

“We always used to joke that he was off in la-la-land,” says his sister Lisa Rober Henderson (BS ’01).

Rober didn’t talk until age 3 or 4, and, by his own admission, he was spacey. “Everyone just thought I was really dumb,” says Rober. In fact, when he took his first standardized test in the third grade and scored off the charts, his mom was in disbelief, he recalls. “She was like, ‘There’s a mistake. This is definitely not my son.’”

It’s not that she wasn’t proud of him. “I grew up creatively encouraged,” says Rober, crediting his mother, who celebrated and snapped pictures when he nailed together two wood blocks and called it a violin or donned swim goggles to cut an onion.

It’s just that Rober’s creativity often evinced itself in . . . less-cute ways.

“Being the annoying younger brother was always really important to me,” says Rober. That kid-on-Christmas giddiness he gets when talking about his latest YouTube build also appears when recounting how he once brought his sister a glass of white vinegar when she asked for water. “Like, that’s not even that funny!” Mark says, nearly crying he’s laughing so hard. “But anytime I got the reaction, that was, like, my fuel.”

Even as he excelled in soccer, all things social, and school—falling hard for math and physics—Rober never grew out of his scheming ways. “Four times growing up,” Rober says, his father sat him down for this talk: “Mark, you have to get more serious. You can’t go through life with this attitude.”

“What up now, Dad?” Rober cracks. “I make a living doing pranks.”

His shenanigans have connected him to kindred spirits, like late-night comedian Jimmy Kimmel, who has hosted Rober on his ABC show six times. The friends have a Discovery Channel show in the works, Revenge of the Nerd, that promises to prank unwitting citizens for social-norm deviance. (Spoiler: If you don’t return your shopping cart, Rober just might mechanize it and sic it on you.)

“I know it’s juvenile,” Rober says, “but there’s something about maintaining that immature view of the world. . . . If something goes disastrously wrong, I’ll flip it in my brain, I’ll make it fun. If you do that enough, life doesn’t feel quite as heavy.”

Breaking the Mold

Lisa recalls watching her brother’s final BYU engineering capstone presentation. All the other students dressed up, “and here’s Mark, hat on backwards, looking like he rolled in from the beach.” Where some presentations were hard to follow, Rober could break things down and he had the audience laughing—in a presentation about detecting deformations in rods used to pressure fit copper tubing in heat-exchanger units.

“He is one of the most energetic and capable students I have ever interacted with,” says emeritus BYU mechanical-engineering professor C. Greg Jensen (BS ’80, MS ’82), now director of senior design at Purdue’s School of Mechanical Engineering. “You often find engineers who want to pull out the paper and pencil and grind through problem after problem, and clearly Mark was capable of that, but at the same time he very much wanted to realize things, to make and produce things. . . . The mold breaker in Mark is that passion and personality.”

A perfect college example of Rober realizing a creative vision was a freshman-year contraption, made with a metal yardstick, duct tape, and fishing line, that allowed Rober and his friends to access their Budge Hall buddy’s Nintendo 64 when he wasn’t there to let them in. “We would only use it for powers of good,” Rober insists.

Fresh out of college, Rober landed his dream job, working at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), or “Disneyland for engineers,” as he calls it. He says it was luck—he heard about the opening from Professor Jensen, who had just presented research there, and submitted a résumé. But Rober also knew his stuff.

“We start with engineering questions and go until the candidate can’t go anymore,” says JPL engineer Brian K. Okerlund (BS ’82), Rober’s former boss. Rober, Okerlund says, could go and go and go.

This also proved true on the job.

“A lot of engineering designers here like their comfort zone,” says Okerlund. “Mark was always looking . . . to improve his talents and capabilities and help others.”

Take the rats.

“We were in a basement of a building at JPL,” explains Okerlund. Rats were getting in and eating people’s lunches. Maintenance set traps, but it took a few days to catch a whiff after trapping a rat. “Mark said, ‘Nope, no, we’re not going to do this anymore.” In short order, Rober had sensors wired to every trap, lighting up an LED panel at his desk.

By day, Rober worked on rover arms and descent-stage jet packs. Simultaneously he earned a master’s from USC and volunteered for other JPL projects. One, a NASA-wide wiki to capture and share information, won him one of NASA’s top internal honors. Along the way, he left his signature everywhere—sneaking the sitcom alien Alf into a photo-realistic picture of the rover he worked on, meddling with supervisors’ presentations, and launching a NASA pumpkin-carving event that continues to this day.

“I don’t fit the typical engineer mold, but they are my people. I speak their language,” says Rober. “I also have the mind and humor of a 12-year-old. . . . It’s a beautiful combination.”

The YouTuber Life

“I knew one of Mark’s goals was to get a million views on YouTube,” says Okerlund. Sure enough, in 2011, the first video Rober posted to YouTube raked in that and more.

In it Rober debuts a Halloween costume that makes it look like he has a gaping hole in his stomach, an illusion achieved with two iPads connected via FaceTime. The thing went viral.

“I’ve got way more ideas than this,” Rober recalls thinking, and he started sharing more videos, featuring things like a shower-hair mural of himself made to surprise his wife. (“I generally don’t prank her,” he says. “I’ve learned better.”)

Shortly after, Rober left NASA. He’d patented the iPad costume idea and launched an entire line of smartphone-based Halloween costumes. Business was great; Rober sold his company to Morphsuits in 2013 and then worked there for two years. Then, in 2015, an old NASA colleague wooed him away to work at Apple, where Rober spent four years secretly working on virtual reality (VR) for self-driving cars.

Apple is pretty hush-hush until its tech gets released, and Rober can’t talk to the press about his contributions—but Patently Apple says the patents that list Rober as the lead author would be “the invention of the decade.”

No one would have guessed Rober had a full-time gig at Apple, the way he kept churning out YouTube videos and racking up views. Rober says most YouTubers quit their day jobs once they notch 250,000 subscribers. “I hung on as long as I could.” But his first glitter-bomb video “was a real knee in the curve” for the channel. With a huge uptick in subscribers, in 2019 he left Apple to pursue his creative outlet full-time.

Now he can work on anything he cares to dream up. “That’s the cool thing about being an engineer,” says Rober. “You can just will something into existence.” And among Rober’s fan base, it’s almost an expectation: when someone faces a daunting challenge, it’s become an internet wink to simply tag @MarkRober and put the problem in his court.

Life Gamified

People may think Rober can create anything, but it’s harder than his 20-second build montages make it look. Every project involves a lot of mishaps and dead ends along the way.

And that’s Rober’s secret power: framing failure.

In both TED talks Rober has given since becoming YouTube famous, he’s big on failing. It all goes back, he says, to an Italian plumber he came to know well as a kid: Mario. “We’d get to school and ask each other, ‘Dude, what level did you make it to?’” says Rober. Nobody cared how many times he died trying, failing again and again. The trick to success, he says, is to not concern yourself with setbacks. He calls it “life gamification.”

Take his automatic-bull’s-eye dartboard, which predicts a dart’s trajectory and moves itself in half a second to guarantee a perfect shot. It took Rober three and a half years to build, training six stepper motors to respond to six infrared cameras and a motion-capture system. “Each setback stung. It sucked,” Rober recalls. But he learned something every time. “It was always, ‘Let’s hit it again.’ . . . It was the tenacity piece that made it happen.”

Rober has always had this laser focus. “It’s not obsessive,” he says. “Well, kind of it is. . . . It’s sort of a blessing and a curse. If I have an idea, I don’t give up on it. And because of that, I don’t feel like I’ve ever fully failed on a thing because I’m always like, ‘All right, it’s just taking longer than it ordinarily would.’”

“Failures,” he adds, “are opportunities to make successes mean more.”

That dartboard was finicky all the way up to its debut on Jimmy Kimmel Live! “Three freaking years, and it all comes down to this,” Rober recalls thinking as he took the stage, unsure if it would even work. “And the dartboard has never caught a more dead-center bull’s-eye!” Rober exults.

“Not only is Mark a brilliant engineer, he is a wildly creative person who brings things most people can only imagine to life,” Kimmel says of his no-can-fail friend. “He’s like Willy Wonka, without the cavities.”

Hip and Square

Every mechanical-engineering student in BYU professor Larry L. Howell’s (BS ’87) classes knows who Rober is. And they say he’s changing stereotypes. Engineering has never been cooler.

“Mark Rober is leading more people into developing these skills,” says Howell. “It’s an amplifying effect that could be huge over time.”

Laughing, as always, Rober points out a video comment of someone saying, “I became an engineer because of Mark Rober. And now I work on sprinkler heads.”

“You never know what might be the next big thing,” contends Howell. There are endless solutions out there waiting to be discovered, things to improve upon. As far as Howell is concerned, Rober “could be a poster child” for the BYU Mechanical Engineering Department’s goal of developing the most influential engineers in the world. “He’s not pushing the boundaries of science,” Howell notes. “But he’s showing how to apply existing principles in new ways, and that is just as important.”

Of course, Rober’s niece and nephews adore him—most want to be scientists now, and they boast of blue ribbons they won on science-fair projects Uncle Mark helped on, from “Do video games rot your brains?” to “Are beans really the magical fruit?”

It’s not just relatives and wannabe engineers gushing over Rober. His YouTube comments are chock full of notes from parents and kids sharing how they love watching the channel together (Howell himself watches Rober’s stuff with his own autistic son). Commenters commonly project what Rober will be doing in 2040, or they delight in Rober’s humor, brains, and goodwill. Another recurring comment: “Wish this guy was my science teacher.”

Turns out, Rober has similar dreams. He’s getting his teaching credentials, and when the coronavirus hit and schools shut their doors, Rober started livestreaming classes, using prompts like “How to Survive a 5-Minute Fall with No Parachute” to teach scientific principles. He also launched an online Monthly.com course, wherein students can access more hours of Rober instruction than all of his YouTube footage combined, plus engage in Q&As and get feedback on their own builds.

“I crave those aha moments I had back in physics class—when something just clicked for me,” says Rober. “And I crave the feeling of giving that gift to other people.”

Pranking for Good

Rober doesn’t go deep often, says his sister Lisa. “He prefers to stay in the ‘light zone.’” Yet that bubbly, immature nature, she says, might overshadow an enormous heart.

Her favorite Rober builds, for example, have never been shared online. For their mother, who died of ALS eight years ago, Rober and his brother Brian built a special jacuzzi lift. She was also a Griswold-level Christmas decorator, and they devised a huge Santa sled that would sail the cul-de-sac sky, powered by a stationary bike.

In his most expensive video to date, Rober threw a massive surprise party for a fan, Fletcher, because he’d made it to 13 after enduring a year of brain-cancer treatments. Naturally, it involved setting a record for the world’s largest “devil’s toothpaste” explosion—basically a giant, steaming pile of expanding colorful foam.

“A surprise is, like, the most wholesome type of prank,” says Rober, who reveled so much in the plans that he couldn’t sleep. And a prank for a good cause—that’s his sweet spot. In a recent ploy, he played Robin Hood against real-life phone scammers.

Rober has also started dedicating one video a year to explaining some of the world’s biggest challenges, like access to clean water, tapping the top minds working on solutions.

In April he finally shared a piece of his life in a video he had been holding back for two years.

It opens with Rober and his 12-year-old son on the couch, laughing. “In eight years of videos, I’ve never really put him on camera,” Rober tells viewers, because “he is on the autistic spectrum and this is the internet.” Rober has kept his personal and family life private—a decision he’s grateful he made before his channel blew up. His wife, Lisa Earl Rober (BA ’02), prefers to remain out of his videos and media coverage, but the two decided to let their son, now 14, appear on screen for a cause.

As they enter into adulthood, individuals with special needs age out of most resources—a kind of “services cliff,” says Rober. With a livestream fundraiser, he and cohost Jimmy Kimmel aimed to raise $1 million to support transition and adult services for individuals on the spectrum.

The live April 30 Color the Spectrum event, streamed on Rober’s channel, featured pranks and bits from Rober, Kimmel, and a slew of their celebrity friends: Hollywood stars like Jack Black, Maya Rudolph, and Adam Sandler, plus mega YouTubers like Mr. Beast and some celebs with autism themselves, like singing sensation Kodi Lee. In three hours they raised $3.53 million for the Next for Autism organization and even more in the ensuing 24 hours—“a record on YouTube for the amount of money raised in 48 hours,” says Rober. A tsunami of comments and calls and letters voiced not only gratitude but also ideas on how to tackle the issue differently or better.

Rober, the guy who can send robots to Mars and “will things into existence,” says, “I wouldn’t change a thing about my son.” But he proved he could change the world even just a little to make it more accommodating.

Speaking of his son and others with special needs, Rober says that one doesn’t have to contribute to GDP or cure cancer to have a successful life: “The best definition of success I can think of is whether you leave the world better than you found it.”

In that vein, Rober hopes he’s making the world a little better, a little smarter, and a little more fun with his layman’s explanations, perseverance, and, sure, immaturity. A prank, he’s shown, can go a long way in this world.

Brittany Rogers, a former editor of this publication, lives in American Fork, Utah.

Feedback Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.