A renowned religion professor for more than four decades, Richard Cowan is guided by insightful perceptions of the world around him.

Photo by Bradley H. Slade, 94

Richard O. Cowan tells of a game he used to play as he strolled across campus in the evening. Walking to his office in the Joseph Smith Building, he thought of the trip like an airplane’s travels across the skies, making its way from beacon to beacon.

Beacon one: the blowing hot-air vent northeast of the Kimball Tower.

Beacon two: a fan on the Eyring Science Center.

Along the way were other turning points, such as sidewalk lights or prominent cracks in the pavement.

The game follows a theme Cowan has repeated many times in life—he likes to know where he’s going. Whether in the back roads of Mexico, on the hillsides of Jerusalem, or under the stars in Egypt, Richard Cowan is a human compass. He is a man who finds comfort in knowing where he stands in the vast expanses of the universe.

And after 43 years as a professor of 20th-century Church history, the longest tenure in the history of BYU Religious Education, Cowan has long since found a home. A respected speaker and author, Cowan has received nearly every teaching honor possible, including the Teacher of the Year Award, the Karl G. Maeser Distinguished Faculty Lecturer Award, and in 2003, the Phi Kappa Phi Distinguished Faculty Award.

But there’s also an interesting footnote on Cowan’s vita, a handful of syllables that partially explain his love of location—retinitis pigmentosa (RP).

Leaving Cowan legally blind since childhood, RP has steadily reduced his vision, causing it to fade from the vague outlines of his youth to the near complete darkness of recent years. “About two or three years ago, my vision took a sudden nosedive, and now I can sometimes get just a glimpse of a light,” the 70-year-old Cowan says. But with the same optimism that has carried him from beacon to beacon, he explains, “I guess I sometimes have thought of the situation as more of an adventure.”

To deny Cowan his blindness would rob him of the remarkableness of his accomplishments, but to dwell on it would too narrowly define him. More than his lack of sight, Cowan is known for his scholarly achievements, kindness, and professionalism. In the words of Arnold K. Garr, ’86, Cowan’s longtime friend and a fellow professor of Church history, “If there were such a thing as a lifetime achievement award in our department, I believe Richard deserves it more than anyone else—for his balance of scholarship, citizenship, and teaching. He is the consummate Christian scholar, or gentleman scholar, if you will.”

A Sense of Direction

Cowan has been endowed with the ability to perceive his path clearly, in both a literal and figurative sense. For most, his lack of sight is imperceptible. He moves so deftly and functions so smoothly that often his is the case of the blind leading the sighted.

Garr recalls a time several years ago when he worked as the Church Educational System institute director at the University of Colorado. That particular week he had invited Cowan and his wife, Dawn, to conduct a fireside. After picking up the Cowans from the train station, Garr got lost in the maze of side roads emanating from the station. That’s when Richard spoke up and asked Garr what the road signs read. After Garr told him, Richard offered, “Oh, just go up to the next road and turn left.”

Sitting in the back seat with a map in hand, Cowan knew the road to take—though he couldn’t see and had never been in that neighborhood before.

Cowan began making “Braille maps” during his early travels on speaking assignments. With the help of his mother, Edith, Cowan created these specialized maps so he could orient himself on his trips. Tools with tracing wheels produced raised solid lines for roads and dotted lines for boundaries; thread represented freeways; bits of cloth and other material mapped out parks and various public locations. Armed with his maps, Cowan turned Columbus, a modern-day navigator of concrete seas. Over the years he’s assisted bus drivers and, on more than one occasion, has given his wife directions even without a map.

“He just has a timing instinct,” Dawn says. “He’s very conscious of where he is; he has a tremendous sense of direction.”

This timing instinct and sense of direction also guide Cowan in his spiritual life—he has carefully considered his turning points over the years, mapping out decisions with the direction of divine inspiration.

Born during the Great Depression in 1934 in Los Angeles, Cowan’s duality of kindness and hard work was forged by his parents, Lee and Edith. Lee was the softer of the two, “friendly and sweet,” while Edith was a “more forceful type personality, one determined to succeed and work hard,” Cowan says.

Even though Cowan eventually had to attend special schools as his sight worsened, at home Lee and Edith treated him and his sister, Jean, equally. Part of his to-do list included tending the lawn and doing dishes. “One lesson I grew up with was I was still expected to do my best, to carry my load,” Cowan says.

While Cowan missed out on backyard boyhood ball games, he took a keen interest in the world around him. He built models, played with shortwave radios, explored the neighboring hillsides, and even formed a science club. He yearned to understand the world he could barely see. Edith bought educational paperback books on plants, the weather, and the solar system. Cowan couldn’t read the print but would hold the books up close to see the pictures. Edith also took her son to the airport and the harbor, places “where you could experience things,” he says.

A master of the scriptures, Cowan’s hands gracefully make their way through a chapter in Alma. He jokes that it’s nice not to be tied to his notes while he’s teaching – he can read and look up at the same time. Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94.

“My folks, particularly my mother, saw to it that I had things that would stimulate that kind of educational interest.”

Education and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have proved pivotal in Cowan’s life. After graduating from high school in 1951, he attended Occidental College and began pursuing a degree in political science. Traveling to and from the Oxy campus in Los Angeles on the number 5 streetcar, Cowan pondered a future as a teacher or lawyer, careers in which he had heard of other blind people succeeding.

After two years at Oxy, Cowan received a mission call to the arid Spanish-American Mission. This past year, Cowan has been reflecting on his mission, periodically reading through his journal to see what he was doing exactly 50 years ago. At a recent family home evening, Cowan shared the entry dated March 7, 1954—a turning point.

Elder Cowan had been out about six months, and he was training his companion, Elder F. Melvin Hammond, now a member of the Church’s First Quorum of the Seventy. The pair traveled 120 miles to attend a mission conference and hear from a General Authority. After basking in what Cowan describes as the “spiritual afterglow” of his contact with a General Authority, Cowan wondered what he could do to continue having these kinds of spiritual experiences.

“The impression was ‘Teach religion at BYU,’” Cowan recalls. “At that point I was balancing between teaching and law. That’s the day that I made the decision to do what I’m doing—in Las Cruces, New Mexico.”

Returning from his mission in 1956, Cowan set off on the road to teaching religion at BYU. At Occidental he excelled in his studies and was elected Phi Beta Kappa. During this time, he continued to keep in touch with a sister missionary whom he had met on his mission, Dawn Houghton. Determined to not distract Sister Houghton in her service, Cowan began each letter, “Dear Sister Houghton,” and discreetly concluded, “Sincerely, Elder Cowan.”

In August 1958 Sister Houghton became Mrs. Cowan. Dawn said she would work to help the young couple through school, but another turning point came when Richard was awarded a Danforth Fellowship. This all-expenses-paid academic honor would take care of the Cowans financially until Richard completed his doctorate.

Having been accepted for graduate studies at Stanford University, Cowan met with officials at the History Department. Determined not to waste time, Cowan expressed a desire to get his master’s and doctorate in three years, an idea the administrators balked at.

Setting to task, Richard diligently studied and Dawn faithfully helped read his texts. In May 1959 the Cowans received notice that Richard had been selected to receive a $500 scholarship that the president of the United States, Dwight D. Eisenhower, would present at the White House.

Thinking back on his meeting with the president, Cowan says, “I had determined that this would be a missionary experience for me. And so I thought, I want President Eisenhower to know that I’m a Latter-day Saint.”

When the president presented Cowan with a check and asked what he planned to do, Cowan pointedly responded, “I plan to teach Latter-day Saint Church history at Brigham Young University.”

Cowan’s visit was reported in a Time magazine story, where Cowan was referred to as “a Mormon from Salt Lake City.”

“Actually I was a Mormon from California,” Cowan jokes, “but I thought, They got the important part right.”

Back at Stanford Cowan proved his doubters wrong, strolling out with both a master’s and a PhD in three years. And he kept his word to President Eisenhower; with the help of fellow Danforth Scholar Daniel H. Ludlow, a religion professor at BYU, Cowan was offered a position in 1961. Faced with initial skepticism regarding whether a blind professor could succeed, Cowan set out to find his place in the world of academia.

“I felt that I was on trial; I knew that I was on trial,” Cowan says.

However, all doubts were removed by May 13, 1965. That day in the Smith Fieldhouse, in front of 17,000 students, Cowan received the Professor of the Year Award—an honor voted on by students.

Visionary Teaching

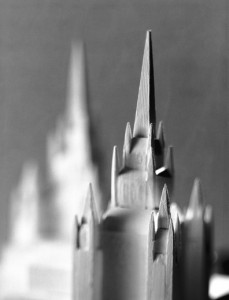

Small enough to hold in your hands, the majestic San Diego California temple stands in miniature, each of the more than 100 pieces carefully measured to scale by Cowan. Through the years Cowan has fashioned himself into an eminent authority on LDS temples, and, wanting to understand the structures architecturally, he has enlisted the help of students in building the small wooden temples. Cowan has constructed more than 12 so far, the students cutting each piece to the scale determined by Cowan, who glues them together. The students then paint and adorn the models with landscaping. Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94.

After 43 years at BYU, Cowan still loves his job and has worked past the standard age of retirement. “I just don’t think of what I do here as work or a job. It’s an opportunity,” he says. From 1994 to 1997 Cowan was chair of the Church History Department, and over the years he has taught a variety of courses, including classes about temples and 20th-century Church history—specialties he adopted shortly after arriving at BYU.

In class Cowan orchestrates a multimedia juggling act. Overhead projectors whir, the in-class computer system springs to life. “Anyone want to place bets about whether the system’s going to work for me?” he jokes as he works seamlessly between the overhead projector on his right and the movie screen to his left. A lively lecturer, Cowan peppers his commentary with clever, subtle humor, which has been the subject of a “Campus Comedy” anecdote in Reader’s Digest:

At Brigham Young University, I was fascinated by the ease and calm efficiency with which Dr. Richard O. Cowan handled our class, though he is almost totally blind. He always injected just the right amount of personal warmth and humor into his scholarly material. One morning during his lecture, as he ran his fingers over a page of his Braille lecture book, I noticed a rather panicked look come over his face. Then, after some quick fingering, he uttered an audible sigh of relief.

“Whew!” he exclaimed. “For a minute I thought somebody had sat on my notes!” [Reader’s Digest, April 1967, p. 94.]

Jokes aside, Cowan is a master of his material, a calm, composed conductor who has used his disability to his benefit in the classroom. Instead of standing and writing on a board, Cowan brings the 20th-century history of the Church of Jesus Christ alive in his interactive, firsthand-account lectures. Having lived through most of the century he teaches about, Cowan relates parts of the material from personal perspective and teaches other aspects with various visual aids.

“I was in the Church Office Building in 1978 the day the announcement was made that all worthy males could receive the priesthood,” Cowan says as he moves around the classroom, from the podium to beside the desk and back to the podium. “I rushed up to the Public Relations Office on the 25th floor—lights and cameras were everywhere.”

It’s only when Cowan tries starting a movie about the priesthood revelation that the conductor momentarily drops the baton.

“Do we have any reason to believe something’s coming?” he asks pleasantly as he tries rewinding the tape. He rattles off a few more facts about the priesthood revelation and then asks, “Does it look different this time?” waiting for a picture to appear on the screen. Only in brief moments like these—when he grazes a chair on the way into class or has problems with the computer—is Cowan’s blindness noticeable. Yet his lack of sight has never deterred him from achieving his purposes in class.

“I have generally two objectives in any class that I teach. The academic objective: I hope that you will become an expert in whatever it is. On the spiritual side, I would hope that you gain a deeper commitment to the gospel,” Cowan says.

Cowan’s classroom competence spills over into his office, where an old Braille typewriter sits squarely in front of his chair. He zips out notes to himself with machine-like efficiency and places them in a neat pile for future reference.

Despite working long hours and Saturdays, he keeps his characteristic gentility; his schedule is never too full for colleagues and students. A lifelong enthusiast of model railroading, Cowan maintains a four-by-eight board with a double loop of track in his basement. When fellow railroading hobbyist Richard E. Bennett, ’72, a faculty member from Canada, recently completed work on his model track, Cowan presented him with a model Canadian National Railroad boxcar from his own collection.

This kind of awareness has endeared Cowan to his colleagues.

“He produces a lot of work, but it’s not at the expense of his relationship with the faculty. He’ll stop and take time, make time, to help you, even though he’s got his own deadlines,” says Garr, noting that Cowan is that way with students too. “He makes you feel like he cares, and he does genuinely care.”

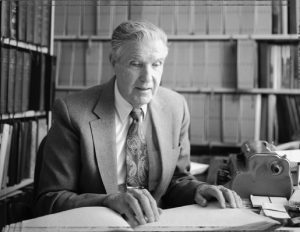

Sound Scholarship

Cowan reads in his orderly office, the walls framed by a 72-volume braille edition of webster’s college dictionary and a seven-volume edition of the Book of Mormon. Adjusting to his blindness, Cowan has also purchased special versions of games such as scrabble so he can play with his children and grandchildren. Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94.

Cowan’s fountain of classroom knowledge springs from years of dedicated research and writing. Cowan’s patriarchal blessing tells him, “You will raise your voice and wield your pen in declaring salvation to our Father’s children.” At the time he received the blessing, he wasn’t sure what that meant. But now, the meaning has gained clarity.

In all, Cowan has authored or coauthored 16 books and scores of book chapters, magazine articles, and scholarly papers. His works include Temples to Dot the Earth and Answers to Your Questions About the Doctrine and Covenants.

Cowan possesses a knack for editing, honed by years of writing, and colleagues and students look to Cowan for assistance. “He’s literally read and edited everything that I’ve written for publication,” says Garr. “He’s truly been a great mentor to me.”

In the world of editing and writing, where the work progresses like solving a Rubik’s Cube, authors or student assistants read aloud to Cowan, who does the editing in his head. No computers. No hard copies. No red pens. Just memory. “I think the Lord has compensated him for not having sight by having a tremendous memory,” Dawn Cowan says.

Of his own writing assignments, one of the most important was working on the Gospel Doctrine Committee for the Church. From 1975 to 1993, Cowan helped write the teaching manuals that would be used by instructors throughout the Church. He contributed lessons to the manuals for the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Old and New Testaments.

Elder Hammond, ’58, has followed the work of his former mission companion over the years. “What impresses me most about him is the true scholarship of the man—he doesn’t leave anything un-turned. He is thorough and accurate,” he says. “And after he has got his information, he writes it very factually. I enjoy what he has done.”

In contrast to the publish-or-perish mentality of many academics, Cowan writes because he enjoys sharing his knowledge. He has adopted the writing philosophy of former dean Robert J. Matthews, ’55: What if Mormon had only taught and never written?

“In the classroom,” Cowan says, “I can reach maybe 50 students, or I can reach thousands through something I might write. The philosophy is just to share.”

To conduct research for his writing, Cowan and student assistants have spent countless hours in libraries, the Church archives, and the Utah State Historical Society, transcribing, photocopying, and recording notes. Cowan has made meticulous notes in Braille during interviews with individuals who had connections to the events he was writing about. And though he’s already assembled a large body of work, he continues to refine his writings. Currently, he is revising Temples to Dot the Earth to cover the many changes since he first published it in 1987.

Cowan’s research has been enhanced through his travels, having visited the Near East, Europe, and South America. In fall 1989 Cowan, Dawn, and two of their daughters spent the semester at BYU’s Jerusalem Center, where he taught Old and New Testament courses. Cowan remembers the atmosphere and the close association he enjoyed with students.

“Living there gave us a more in-depth kind of experience,” Cowan says. “It felt great. We could hear the Muslim call to prayer five times a day. That just underscored the idea that we weren’t in Provo.”

At the Jerusalem Center, he conducted weekly field trips to various sites, including Bethlehem, Nazareth, and the Sea of Galilee, where he taught a class on the shore at sunset. “When I think of who else taught on the shore of the same sea,” Cowan says, “it seemed like a special experience and quite a responsibility to be teaching His gospel at that same place.”

Guiding Insight

Standing on the shores of Galilee reflects the diligent quest of Cowan—who has spent most of his life teaching the gospel—to follow in the footsteps of the Savior. His collective past of turns has led him across the country and around the world, from the urbanity of Los Angeles to the tranquility of the Joseph Smith Building. But more important than where his journeys have taken him is what they’ve done for him: Cowan’s sightless travels from beacon to beacon have strengthened his faith in the gospel.

“Because of my visual challenge, I have come to feel more reliance on the Lord than I might otherwise do, and for that I’m grateful,” he says, sharing one of his favorite scriptures from the Doctrine and Covenants: “Be thou humble; and the Lord thy God shall lead thee by the hand, and give thee answer to thy prayers” (D&C 112:10).

Cowan has relied on this injunction to pray, but he wisely notes, “He chooses when to help.” Gratitude for the assistance he has received over the years keeps Cowan from dwelling on what he hasn’t seen or been able to do.

“Blindness has been an inconvenience to work around, but I guess I’ve been more concerned about doing what I need to do,” he says. “Of course I would like to be able to see perfectly well and enjoy the beauties of nature and the smiles of loved ones, but I am just grateful for the help that I’ve had.”

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.