Flight of the Mary Bee

Discouraged from dancing as a child, the founder of BYU’s International Folk Ensemble turned her dreams into reality.

By Charlene Renberg Winters (BA ’73, MA ’96) in the Spring 2017 Issue

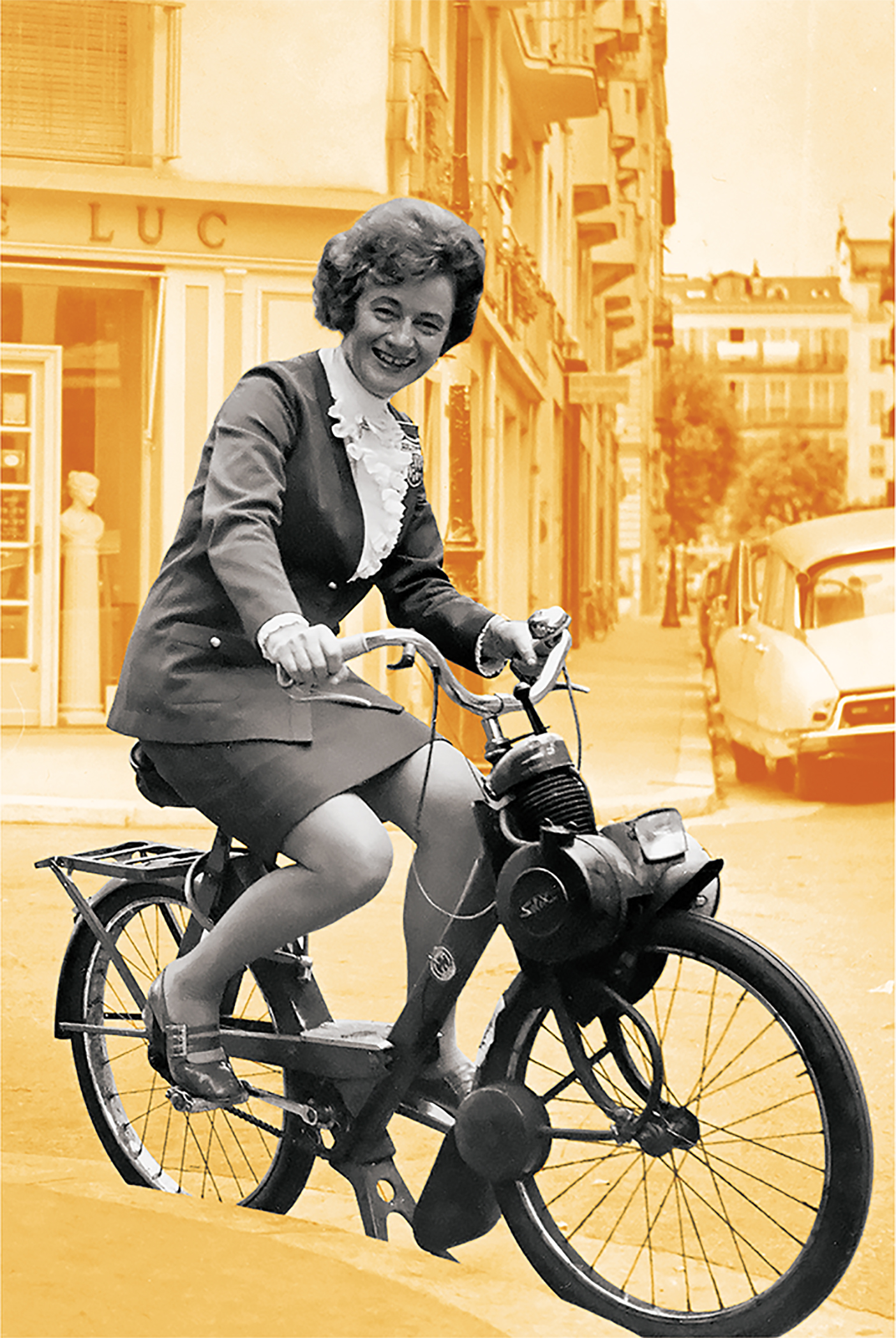

You might find her driving around Utah County in her black KIA Sportage or soaking up the sun on a beach in San Diego or strutting down the supermarket aisle in an elegant suit and pearls, clicking her heels with the vivacity of someone in her prime.

Mary Bee Jensen, founder of BYU’s world-renowned International Folk Dance Ensemble, may now stand at the brink of 100 years old, but there is nothing teetering about her. “I drive my own car, live in my own home, and maintain a Facebook page,” says the self-described firecracker, whom everyone knows simply as Mary Bee. “I have great luncheon dates with my dancers, dote on nine grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren, and continue to move full speed ahead.”

“Full speed ahead” is an apt summary of the life of the woman who dreamed up BYU’s monumental folk-dance program—385 students strong at its peak—marching, twirling, and clogging a million steps across the globe in tour after international tour. Along the way she spread goodwill for the United States, the Church, and BYU and touched thousands of student lives.

“The Lord put me here on earth to influence and be a force for good for young people,” Mary Bee says. “I wanted ‘my kids’ to experience the best of life, and dance was the vehicle.”

Now 60 years after founding the program, Mary Bee Jensen is still influencing those kids—many now retirees themselves. Hundreds plan to join her in May for her birthday bash, where there’s been talk of dancing. For Mary Bee Jensen, who calls herself a “perpetual mover,” 100 is not too old to dance.

Dance Dreams Deferred

Mary Bee Jensen’s former dance students speculate that when she emerged from the womb in 1917, she was doing the polka. And although Mary Bee cannot remember a time when she was not dancing, she grew up in a Presbyterian family that discouraged the activity—her grandfather considered it sinful. Unable to take private lessons during her youth in Depression-era Provo, Mary Bee took advantage of the school district’s dancing, tumbling, and marching opportunities, which she says were exceptional, better than those of many university programs at the time.

An outsider in the Mormon community, Mary Bee turned snubs into motivation. She immersed herself in community activities, telling herself she would be as good as—if not better than—anyone else. Determined to become the most popular girl in school, she received Provo High’s “all-around girl” medal during her junior and senior years.

And she began to dream of dance and where it could take her. “My dreams often exceeded reality,” she says. “I just had to wait for reality to catch up.”

She deferred those dreams again when her parents sent her to a Presbyterian college in Missouri to earn a degree and be instructed in protocol, dress, and manners. Again, no dancing allowed.

Like her father, Mary Bee studied the sciences, and after graduating she found work as a PE and dance instructor at Jordan High School near Salt Lake City. While there, in 1940 she met—and four weeks later married—Donald Jensen. A former state basketball and football star, Jensen had recently returned from a Mormon mission to Denmark.

When the couple relocated to Provo in 1944, Mary Bee “started hanging around the [BYU] dance department and taking classes.” She often played the piano for physical-education professor Leona Holbrook, who taught folk dancing among other activities. In the early ’50s, Holbrook offered Mary Bee a temporary spot on the PE faculty to teach archery, basketball, soccer, and dance.

Finally, she had an outlet for her pent-up dance ambitions, which, she says, “exploded into a 33-year career in dance.”

Her shift toward folk dancing began modestly enough in 1956, when Mary Bee organized six couples who rehearsed in the old Women’s Gym on University Avenue. Mary Bee had once thought her future would include work as a professional square-dance caller (she even had several namesake dances—the Mary Bee, Be Merry, and Bury Me).

A bigger opportunity presented itself when a BYU professor happened upon a practice and advised Mary Bee to visit Jane “Janie” Thompson (BA ’43), director of BYU’s Program Bureau, which provided performing opportunities for students. Thompson added Mary Bee’s dancers to the bureau, and Mary Bee would often perform at local venues with her older son, Donald, in a mother-son segment.

“I truly loved performing,” she says. “I was attracted to the glow of the stage lights beaming on my face, the energy of the dancing, and the darkened auditorium filled with people.”

As much as she appreciated having the folk dancers as part of the Program Bureau, however, Mary Bee began to envision a dance program where the world would be her campus.

Show on the Road

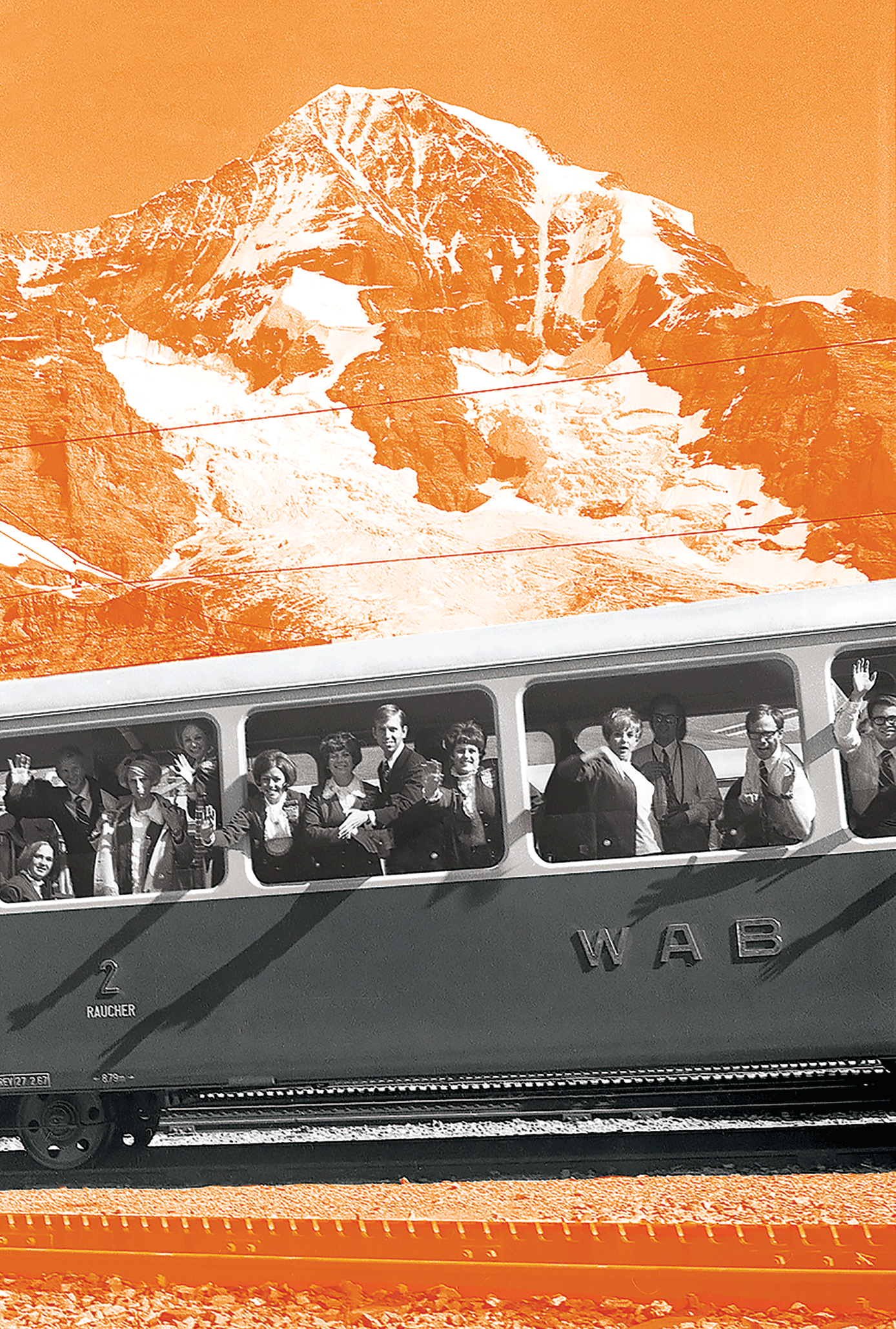

Cobblestones covered the Grand Place, an elegant town square surrounded by gilded houses and fine restaurants in the heart of Brussels, Belgium, where more than three dozen BYU folk dancers were scheduled to perform in 1974. Knowing the uneven surface would challenge their guests, town officials erected a temporary stage.

But under the dancers’ weight, stomps, and clogs, the structure began to wobble. Two musicians toppled from the back of the stage; seconds later, mid-twirl, two dancers fell. In a moment, their petite redhead director rushed forward to patrol the sides of the stage and “catch” any other falling performers. The city called upon the local fire department for help, and firemen used their backs to reinforce the stage. But when the stage began to collapse from the center, Mary Bee diverted everyone from the damaged structure. With their trademark vivacity and dazzling smiles, the students finished their finale on the cobblestones—much to the relief of the heavily perspiring firemen.

It was just another day on tour for Mary Bee Jensen and her international ensemble. “You were always on an adventure with Mary Bee,” remembers former folk dancer H. Patrick Debenham (BS ’73), who recently retired from BYU’s modern-dance faculty.

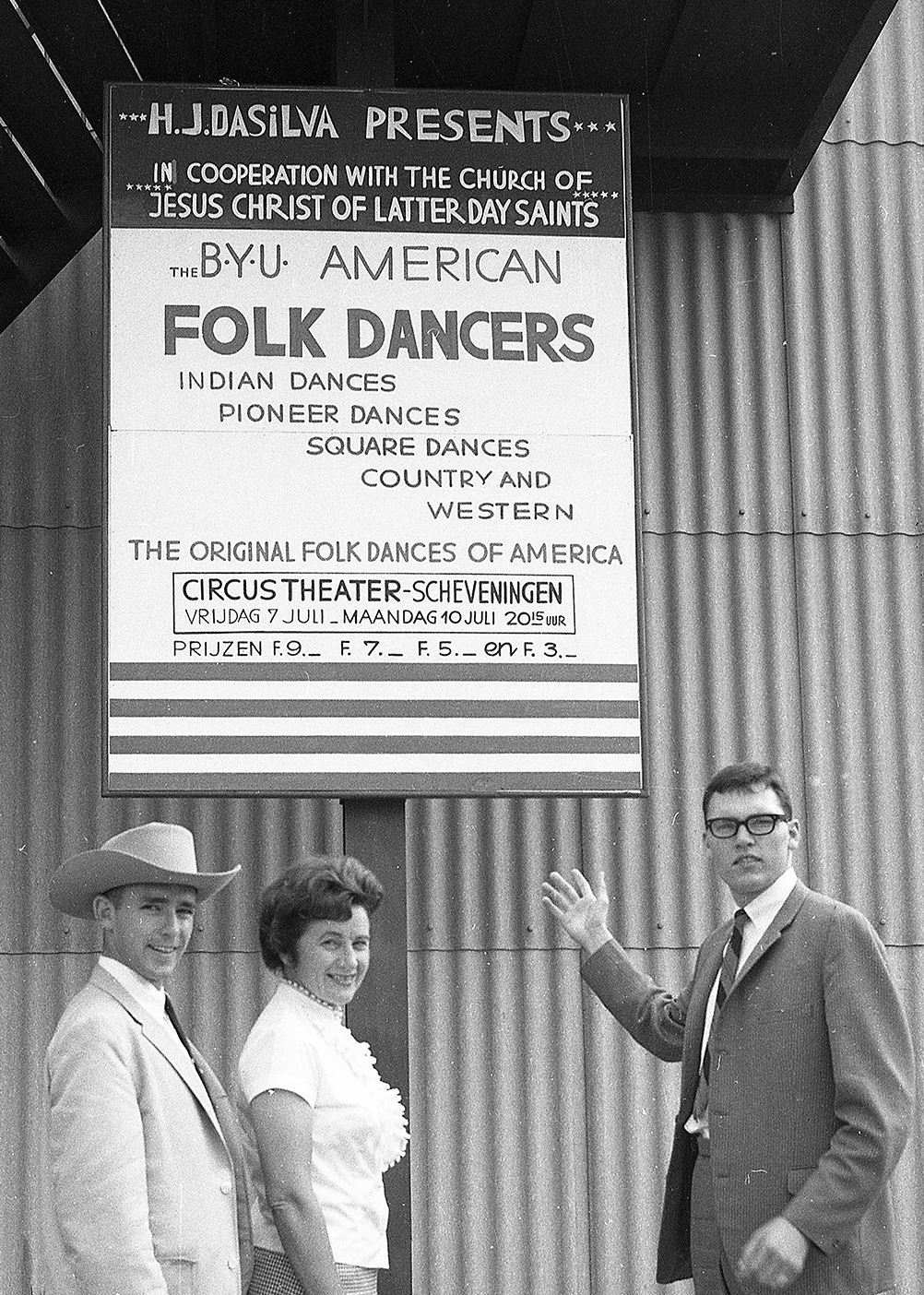

When Mary Bee first announced her ambitions for international travel in the early 1960s, BYU administrators were cautious. She would need to find her own funding. With no easy means to finance the first trip—a 1964 European tour—the Jensens took out a personal loan through BYU for $26,000 (worth nearly $200,000 today). Funding secured, they boarded a plane for Denmark with 28 energetic students, a few bookings, and a bushel of faith.

Debenham says Mary Bee proved, at home and abroad, to be a master at getting people to embrace her vision. “People rarely said no to Mary Bee—and if they did, she found another way to get what she needed. The word impossible simply did not exist.”

Throughout the inaugural tour, Mary Bee spent hours on the phone contacting people from nearby towns and villages to add shows along the way. From Denmark, they advanced to Germany, Austria, Italy, France, and Belgium. Mary Bee immersed her students in the local culture and researched costumes and dances from the countries as they traveled. She was building the framework for her next 20 years.

Although students learned dances from around the world, at international festivals it was customary for performers from each country to highlight their own native folk dances. Thus the BYU group presented American folk dances: square, clog, swing, Native American, western line, Appalachian, pioneer, and Charleston. Occasionally, for fun and friendship, Mary Bee traded costumes with another country’s troupe and they taught each other their native dances.

After returning from the six-week tour, Mary Bee filled the next year with stateside concerts, earning enough to repay her debt in full and on time. The next year, 1966, the troupe headed back abroad—this time on an ambitious 87-day tour, which would be its longest.

Over the next two decades, Mary Bee and her kids “danced their way across the world and into the hearts of countless thousands of people,” says John G. Kinnear (BA ’78), who toured with Mary Bee and the dancers in 1971.

Even with experience under Mary Bee’s belt, touring remained an arduous endeavor with occasional mishaps. Today BYU’s Performing Arts Management team handles bookings, uniforms, cultural training, and other details, but back then those all fell to Mary Bee.

She recruited her students to haul around costumes, equipment, and props. Nina Woodbury Booth (BA ’70) recalls carrying over her shoulder a drawstring cowboy boot bag that held live snakes for Native American dancer Kenneth R. Larsen (BA ’67, PhD ’73), who would wind the snakes around his neck during his Snake Dance.

“In those days, plane security was quite relaxed,” Booth recalls. “We tossed carry-on baggage onto open shelves. I had put the snakes there, and while we were flying, a Scandinavian flight attendant approached me and whispered, ‘Excuse me, is there something alive in there?’”

Not sure what to say, Booth hesitated and was relieved when the attendant walked away, saying, “Don’t worry about it. I can handle anything except snakes.”

One of Mary Bee’s best recruits was her supportive husband, Don. “He served as the tour manager and eased the rigors of the road,” she says. “The students loved him and saw him as a quiet, solid father figure.”

“Don Jensen was an angel,” says René R. Alba (BA ’75), a former dancer and current Area Seventy. “Knowing Mary Bee and Don inspired me and Kathy [Tenny Alba (BA ’74, MCD ’77)], my wife and former dance partner. It still does.”

“I loved touring, and if we had glitches, Mary Bee solved them,” says F. Russell Wood (BA ’71), who played the banjo with the group’s traveling band. “We were in Denmark once and arrived to discover our concert had been canceled. We were counting on the show’s revenue to keep us going. Mary Bee immediately grabbed the phone and found us a new venue in Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens. We were thrilled to perform in this famous amusement park.”

Because Mary Bee often added performances along the way, the schedule became so crammed that more mundane tasks were delayed. One year the ensemble had no time to wash their costumes. “Believe me,” says Wood, “they needed to be cleaned.”

Recognizing the challenge, Mary Bee arranged for the local mission president and wife to launder the dancers’ clothing while the team snagged some welcome sleep in the foyer of the church where they would later perform.

Edwin G. Austin Jr. (BS ’78, MA ’80), who succeeded Jensen as director in the mid-’80s, remembers another costume challenge on the way to a festival in Zakopane, Poland. It was 1977, and the team encountered thorough Soviet Union security checks. Czechoslovakian soldiers stopped them for an inspection, and, for whatever reason, they removed the train’s luggage car.

“We had our clogs, and the musicians had their instruments,” Austin says. “But with nothing else besides the clothes on our backs, we performed five nights in our travel outfits.”

The costumes arrived in time for the finale, and judges honored the BYU team with five awards, including the Golden Axe, the festival’s top prize.

The Mary Bee Finishing School

Former student dancer Booth still has occasional “Mary Bee dreams”—the ones where she panics over being on time, having everything she needs, or making quick costume changes.

“These dreams aren’t nightmares,” she explains. “I just wanted to do things right and have Mary Bee proud of me.”

Although many dancers remember Mary Bee as a motherly figure, this was a mother with high expectations for her kids. Even before Jensen converted to Mormonism in 1979, she insisted that her students be sparkling, courteous ambassadors representing the best of BYU and the Church, as well as the United States more generally.

Bonnie Hansen Romney (BA ’71) said her five years dancing with Mary Bee helped to soften some of Romney’s bossy tendencies. “Mary Bee inspired me to be my best and to exhibit graciousness at all times.”

And she expected students to learn everything possible from their tour. “Mary Bee knew many of us were having a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” says Austin. “So if we dozed on the bus, . . . she would wake us, declaring that we could sleep when we got home.”

“That is absolutely correct,” Mary Bee says. “I didn’t want anyone sleeping on the job, so to speak.”

For Mary Bee, being an ambassador meant looking the part. “We needed to look distinctly American, not only with our dances but also with our style and our behavior,” she explains. She asked female dancers to wear their hair no longer than shoulder length—she didn’t want them confused with European dancers who maintained long locks to show off their braids.

Students recall other staples of the “Mary Bee Finishing School,” as they called it. Vickie Scholes Austin (BA ’76, MHE ’77) remembers a requirement to wear modest pantaloons under their blue German dirndls—in a time when pantaloons weren’t exactly easy to find. And she recalls Mary Bee’s insistence that students try any food they were offered. “If we didn’t like it, we could spread it around our plate and make it look as if we had eaten something.”

Believing courtesy dictated sampling any and all cuisine, appetizing or not, Mary Bee recalls only once when she bypassed something on the platter—something that had tiny legs and hair.

“I saw the smug looks on my observant students,” she says.

Booth notes how the social graces she learned in folk dance have continued to bless her life: “[Mary Bee’s] finishing-school principles have stayed with me and were particularly helpful when my husband, Russell [BS ’68, MS ’69], and I served a mission in Nigeria.”

She can remember lying in bed after a tour and marveling about the experience. “Here I was, just a little girl from Salt Lake City, who had been speaking with dignitaries and community leaders abroad just a few days earlier. Mary Bee trained us to be outgoing and gracious ambassadors. I learned so much more beyond dancing under her training.”

Ovations and Encores

As Mary Bee Jensen and her ensemble traveled the world, their reputation and friendships grew. The BYU team formed particularly close bonds with dancers from Turkey and Ukraine. Such relationships were evident at a 1982 festival in Confolens, France, during one of Mary Bee’s final tours. A grand finale highlighted the BYU dancers. As Mary Bee approached the stage to acknowledge the applause and shouts of approval at the show’s conclusion, she was surprised when the director of the Turkish folk-dancing troupe stepped forward to present her with a bouquet and plaque. Mary Bee was more astonished seconds later when flowers began descending over her and her dancers, ticker-tape style. Thrown by Turkish dancers situated in the loft and side stage, the petals piled up two inches deep on the stage. With tears in their eyes, the dancers exited the theater only to find themselves flanked outside by cheering Ukrainian and French friends.

With assurances that the program she founded would remain resilient and robust, Mary Bee retired in 1985. But that was hardly her final bow in the world of international folk dancing. The very next year she became the founding president of the National Folk Organization of the United States of America.

In addition, since 1974 she had served as the U.S. delegate and adjudicator for the prestigious International Council of Organizations of Folklore Festivals and Folk Arts (CIOFF). For more than 30 years she would work with the 89-nation-strong organization to advance folk dancing.

At BYU Mary Bee’s influence is still felt in the Marriott Center each year at the Christmas Around the World concert, one of her earliest projects. Created in 1960, the holiday concert presenting international dances to BYU audiences has drawn thousands for nearly 60 years.

But Mary Bee Jensen’s greatest impact is likely felt in the lives of her former dancers and their families, many of whom met and married while on the team and whose children and grandchildren would later win a coveted spot in the ensemble. And some kept on folk dancing—like Romney and Shawnda Peterson Bishop (’76), who used Mary Bee’s contacts to form a youth ensemble that has toured for 25 years.

Thousands of students grew under her influence, many declaring that Mary Bee forever changed their lives. In her quest to help people develop as a whole, Mary Bee was especially happy when she could bring out a more reserved student. Laurel Thais Shelley (BA ’85), for example, initially did not make a folk-dance team when she tried out at the Richards Building. “More than 500 people wanted one of 40 coveted spots,” she recalls. “I was intimidated and reserved. No wonder I wasn’t chosen.” Shelley enrolled in a non-audition folk-dance class so she could prepare for another shot on the team. The second time she auditioned, she showed up with a beaming smile, and this time she made the team.

“Mary Bee respected my efforts,” Shelly says. “She changed how I interact with people, even in the way I [have taught] school and advised a color guard. In a very literal way, she changed my life.”

Garth H. Peay (BS ’72), a former Broadway dancer who performed with Mary Bee’s top team in the ’60s and ’70s, says, “She . . . plucked me from the sidelines and opened my world. I saw firsthand her devotion to introducing people to our faith and to BYU, and I witnessed her unflagging energy.”

With such relationships, built through more than 30 years of classes and tours, it’s no surprise that hundreds of former students plan to be on hand to celebrate Mary Bee’s birthday in May.

Debenham will be there to honor his mentor and friend. He says simply, “She infused my life with light.”

Charlene Winters, a former BYU Magazine alumni editor, is a freelance writer and editor living in Orem, Utah.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.