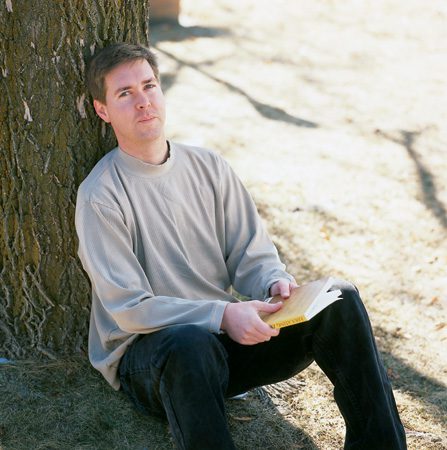

From lab coats to academic robes, from physicians' scrubs to dark suits, Cecil Samuelson has passed through various dress codes in his careers as physician, professor, scholar, administrator, and General Authority. As he takes a new mantle as the 12th occupant of BYU's presidential office, it appears all of his previous roles have combined to make the current one a perfect fit.

When Cecil O. Samuelson was about 2 years old, he decided his nickname didn’t suit him. According to family members, he calmly told his mother to stop calling him “Sammy” and start using his proper name—Cecil. He’s been known as Cecil (or Cec) ever since.

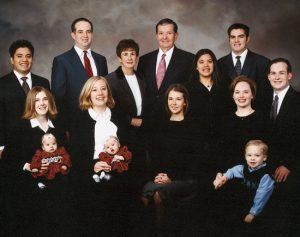

Cecil and Sharon Samuelson have made a life out of responding to invitations to serve. Through a career of successive administrative appointments and a personal life filled with demanding church callings, they have served together. As he comes to BYU, President Samuelson says Sharon is his greatest asset. Photography by Seth Smoot and Mark Philbrick.

That self-confidence and decisiveness were early indicators of achievements to come—renown as a physician and professor of medicine, contributions to significant research in rheumatic diseases, and administrative proficiency in academic, business, and ecclesiastical settings. As the recently named 12th president of BYU, he will combine his strong sense of self with all he’s learned in his various roles.

“I’ve been very fortunate to have had multiple careers,” says Samuelson. “This new experience at BYU is not one that I could have anticipated, and I look forward to it with great enthusiasm.”

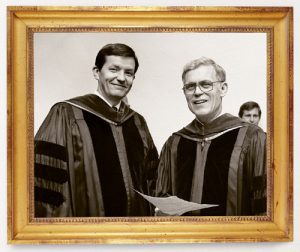

Longtime colleague and former University of Utah president Chase N. Peterson says President Samuelson is “a wonderful choice,” in particular because, as both a scholar and a member of the First Quorum of the Seventy of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, he embodies the meld of faith and knowledge so central to BYU’s identity. “He understands faith, and he lives by it. He understands the intellect and the pursuit of new ideas called research. And he understands that there’s harmony between the two,” says Peterson, a fellow physician.

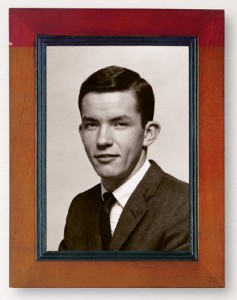

As a young man, Cecil Samuelson thought medicine would be an ideal blend of his interests in science and people. As his career progressed, his generalist sensibilities led him to a wide range of activities. Photo courtesy Sharon G. Samuelson.

R. J. Snow, a longtime associate in various circles and a former vice president at both BYU and the U of U, says that at first glance Samuelson may not be an obvious choice to head BYU, because none of BYU’s 11 presidents has been a medical doctor. But looking just beyond that glance, he says it becomes clear that President Samuelson’s competencies converge ideally for BYU: “I see in him the combination of a person who knows what a university is and ought to be, a person who is completely dedicated to the Church and the kingdom of our Heavenly Father, and one whose interpersonal skills, gifts of brilliance, and spiritually based teaching are just superb. How could Heavenly Father better prepare someone to come here?”

Generalist Practice

President Samuelson began contemplating career possibilities during high school, not long after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I, jump-starting the space race with the United States.

“Any kid who could do a quadratic equation or had an aptitude at all in science was encouraged to become a scientist or engineer,” says Samuelson. “I didn’t know much about engineering, but I thought it was something I ought to do.”

Though he began his undergraduate education at the University of Utah as an engineering major, during his mission to Scotland he discovered he enjoyed working with people. He also liked science, however, and he decided medicine might offer an ideal blend of interests.

Over the next eight years at the University of Utah, Samuelson completed his bachelor’s degree and attended medical school, graduating second in his class. In the middle of medical school, with an inkling he might want to follow in his father’s footsteps as a professor, he made the unusual move of adding to his course load by beginning work on a master’s degree in educational psychology.

“Imagine a second-year medical student adding to his medical training by getting a psychology of teaching degree,” says Peterson. “It’s remarkable.”

Samuelson then headed to Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., for a three-year residency and fellowship in rheumatic and genetic diseases. During his last year there, he worked intensely in the laboratory purifying and sequencing an enzyme. The experience was illuminating.

“As important and intellectually stimulating as that was,” he says, “it became very clear to me that I wanted to spend more time with people.”

Duke offered him a position to continue his research and teach, but the University of Utah also came up with an offer. While he and his wife, Sharon, thought they would eventually return to their roots in the West, they didn’t anticipate going back so soon. But the University of Utah job, assistant dean of admissions and faculty member at the medical school, appealed to Samuelson’s generalist and people sensibilities.

“In most of the major universities at that time in my field, you needed to declare pretty quickly what you were going to spend your life doing,” says President Samuelson. “If you were going to be a researcher, then you’d be a researcher. One of the things that made the University of Utah offer very attractive was the fact that there would be some flexibility to do some things that, frankly, I would not be able to do at Duke or most other places.”

So in this age of superspecialization, Cecil Samuelson became a generalist. Though he has an MD and is board certified in the subspecialty of rheumatology, he has consistently chosen to take on widely ranging projects and responsibilities. Once back in Salt Lake City in 1973, he proceeded to practice medicine, conduct research, and teach and administer in the secular and sacred spheres. Within four years of accepting the University of Utah position, he became acting dean of the medical school. He was also quickly called to service in a married student stake as a high councilor, branch president, counselor in the stake presidency, and then stake president. In January 1985 he became dean of the school of medicine, and three years later he was named the university’s vice president for health sciences. Also in the mid-1980s, he served as a Regional Representative for the Church.

Keeping Equilibrium

As Cecil Samuelson took on more and more responsibilities managing the U’s complicated, almost labyrinthine medical school, his reputation grew for intelligence, fair-mindedness, affability, and broad scope.

“Any hospital, but especially a university hospital, is a difficult place to govern,” says M. John Ashton, executive director of the U of U alumni association and former chairman of the U’s hospital board. “There’s a wealth of strong egos and strong skills. He was able to mediate, negotiate, and bring people together.”

Due to scarce funding, the medical school was dependent on the ingenuity of its faculty and administrators, says Peterson, who was vice president of health sciences when Samuelson served as medical school dean. “Cec and I used to chuckle about how we had a whole bunch of wild-eyed, independent people here all doing their own thing, but we also had to have some coherence—we couldn’t just be all flying out in different directions. But if we didn’t have this great entrepreneurial spirit, we’d be dead.

The way to handle such an operation was to give creative people the freedom to actualize their vision while also holding them responsible. Samuelson, Peterson says, had a gift for helping everyone keep their equilibrium as they worked to balance these competing interests.

In addition to his administrative role, Samuelson maintained other responsibilities at the U—a feat many of his colleagues admire. He continued to teach and conduct research, and he made it a point to keep his hand in clinical work until his call as a General Authority. As a doctor, he was known for efficiency, warmth, and a direct bedside manner. Ellis Ivory, who, as a stake president, called Samuelson to be his counselor, experienced that care directly. “He was my personal doctor for 20 years,” Ivory says. “Most people go up to the University Hospital and it’s a nightmare. You’re there for three hours just trying to see anybody. But Cecil had the ability to cut through bureaucracy. You’d go up there, you’d see him, and you’d be out of there. He has an amazing efficiency without being pushy or autocratic or tough.”

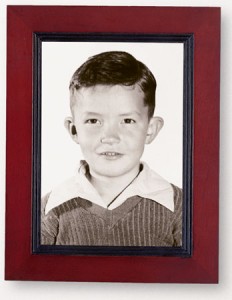

As a young boy, Cecil Samuelson enjoyed baseball and fishing. He later learned to play the saxophone. Photo courtesy Sharon G. Samuelson.

James S. Jardine, an attorney and former chairman of the University of Utah Board of Trustees, says as a doctor Samuelson was a truly open, honest, and sensitive communicator. People Samuelson has cared for have told Jardine that “he told them more honestly and directly the medical circumstance they were dealing with than almost any other physician they’d ever dealt with. You would get it straight from Cec, but it would be done in the most caring way.”

In 1990, after 17 years at the University of Utah, Samuelson was recruited away from academia to become a high-level administrator at Intermountain Health Care (IHC). “What this says of the man is that he’s a superb administrator—but more than that, that he has the confidence of his peers,” says Snow, who was in the University of Utah administration with Samuelson in the 1980s.

After a few years as a senior vice president, Samuelson was named president of IHC Hospitals, and it appeared he was being groomed to be president of IHC itself. But in October 1994 he was called to full-time service as a member of the Seventy of the Church of Jesus Christ. He walked away from IHC without a backward glance. When asked at the time about his choice to leave his career just when he was approaching a pinnacle, he said he had decided years earlier that he would always respond to any calling extended to him in the Church.

As a General Authority, Elder Samuelson served as president of the Church’s Europe North and Utah North Areas and most recently as the Sunday School general president and a member of the presidency of the Seventy. One of his most enjoyable assignments has been attending stake conferences. “Each time you go,” he says, “you meet wonderful people who are devoted, and you see their faith and hear their testimonies. That is just an exhilarating experience.”

Solid Roots

The oldest of five children, President Samuelson credits his parents, Cecil O. Samuelson and Janet Brazier Mitchell Samuelson, for his positive traits. He had a wonderful childhood, he says, with parents who taught him a strong work ethic, honesty, and devotion to church and family.

The Samuelsons were an ordinary family with everyday struggles, such as the time they decided to drink powdered milk to save money for a television. “We didn’t come from a background of either abject poverty or great privilege but from very solid roots—loving parents who worked together,” says Samuelson.

His father was always building things—a couple of homes, a boat, a car. Cecil Sr. came from a family where no one had attended college, but he married into one where six of seven children were collegians. Janet persuaded her husband of the virtues of higher education, and at the age of 25 Cecil Sr. became a college freshman at the University of Utah. He was in his early 40s when he finished his doctorate in educational psychology and joined the university’s education faculty. Thus began the multigenerational Samuelson ties to the University of Utah.

Cecil Jr. clearly admires his parents and deeply values being named for his late father. Commenting on the nickname incident, which he doesn’t remember, President Samuelson says, “I identify strongly with my father. He’s a wonderful man, a wonderful father, and I’m honored to have his name.”

Like his father, Samuelson has found himself comfortable with a hammer in his hand. Early in his career at the U, he spent his evenings for a few years building a Tudor-style home for his family on a dead-end street in the Holladay area of Salt Lake. He subbed out only a few tasks, having learned the trade with his father and while working to fund his education.

These days, Samuelson has less time for hobbies or recreation but does enjoy crossword puzzles, solitary walks, athletic events, and time with his family.

He met his wife, Sharon Giauque Samuelson, 40 years ago, and both joke that their marriage was arranged. Sharon was the elder Cecil’s secretary at the U, working her way through a history education degree. Her employer often told her about his son who was on a mission, and when Cecil Jr. returned, he regularly met his father at his office for the end-of-the-day ride home.

“It took him about four months, and then he asked me out. Neither one of us dated anybody else after that,” says Sister Samuelson.

Friends and family say Sister Samuelson is bright, independent, friendly, and straightforward. The oldest of five children, she grew up in Salt Lake City and attended Highland High School. After graduating from the University of Utah in 1964, she taught fifth and sixth grade until she gave birth to their first son, Cecil III.

“Sharon is an extremely supportive person. She’s very easy to get along with,” says brother-in-law Kent M. Samuelson, a Salt Lake orthopedic surgeon. “She’s a great person—very dependable, not one who seeks the limelight or to make an impression on people. What you see is what you get with Sharon.”

Part of what people get, says eldest son Cecil, is a woman whose husband has been gone much of the time, bringing out in her a quiet but determined independence.

“I try to be supportive but still take time for myself because I think that’s really important,” says Sister Samuelson. She has been a member of a book club for nearly 30 years, attends the Utah Shakespearean Festival in Cedar City with friends, plays tennis, and is an avid fan of the Utah Jazz. Her greatest satisfactions continue to come from the Samuelsons’ five children and three grandchildren.

Competence Without Pretense

Contributing to President Samuelson’s success is one of those rare constitutions that allows him to function on less sleep than most people and catnap as needed. With only a touch of gray skimming his forehead, he looks younger than his 61 years—thanks in part to a daily 45-minute regimen on a NordicTrack. Wherever he’s headed, he walks at a speed that approaches running. “He seems to have the same energy, enthusiasm, and optimism that he did 20 years ago,” says Anthony W. Morgan, a former U of U administrator and current U professor of educational leadership.

Dr. Samuelson speaks as a delegate to the Utah State Medical Association at its annual meeting. He credits his parents for encouraging him and his siblings. “They had enough confidence in us, without being unrealistic, that we could achieve most of what we wanted to do – if we were willing to work hard enough.” Photo courtesy Sharon G. Samuelson.

He’s able to get so much done, says Chase Peterson, because “he’s darn smart. He is very smart. That lets him do more in an hour than the rest of us can do when we muddle along slower.”

His efficiency is legendary, says close friend H. James Williams, a physician who was Samuelson’s partner in clinical practice for 16 years. When Samuelson became stake president, high council meetings lasted three or four hours, says Williams, who served as Samuelson’s counselor in the presidency. “He commented in a presidency meeting that if the Quorum of the Twelve can run the Church in an hour and a half, the stake can run on an hour-and-a-half meeting.” So Samuelson moved the meeting to 6:30 a.m. on Fridays, knowing that most council members would have other commitments by 8 a.m. “We lost nothing in the running of the stake,” says Williams.

Such forceful and energetic traits might add up to overbearing intensity in some personalities, but in Samuelson’s it adds up to competence without pretense. He doesn’t carry a planner, preferring 3 x 5 cards for his daily to-do lists. His parents taught their children to always do the best they can at any job—take the job seriously, but not yourself. “Don’t think you’re too high and mighty,” was a parental message, recalls Kent Samuelson. “I remember one time I was telling my dad about some great things I was going to do, but he said, ‘Don’t tell people about them until you have done them.'”

President Samuelson’s driven qualities are also tempered by a wily sense of humor. When he first told his wife of his call to the BYU presidency, she thought he might be putting her on. “I thought maybe he was teasing me, because he’s a tease in our family. But after a little while I said, ‘I think he’s serious about this.'”

Kent Samuelson says his sibling’s latest position provides an opportunity for an ideal blend of his talents and abilities—a union of intellectual, administrative, spiritual, and ecclesiastical skills that was never quite possible in his assignments at the U or at IHC.

Grandpa Samuelson enjoys a moment with his oldest grandchild, James. Love and laughter are emphasized in the Samuelson home, says Sister Samuelson. “We joke a lot,” she says. “Our family likes to laugh.” Photo courtesy Sharon G. Samuelson.

“I think to be a truly effective president of BYU, you need the academic credentials, you need the administrative abilities, but you also need someone who is well versed in the gospel and who really understands the significance of the gospel and the Church in the overall picture of what’s going on in the world. And that’s where I think he’s especially well qualified. This will allow his personality to really shine.”

President Samuelson says he looks forward to his years at BYU, partly for the same reason he enjoyed being an administrator at the University of Utah: he finds satisfaction fostering an environment where others can succeed. “I continue to get great vicarious thrills from the success and achievements of outstanding people whom I’ve had the opportunity to intersect with in one way or the other. That’s one of the things that is most attractive to me and exciting about this opportunity at BYU.”

University of Utah colleague and fellow physician John M. Matsen says Samuelson has been prepared for this new assignment. “His career is not by chance,” he says. “The Lord was there to help him experience the things he needed to experience for this kind of a culmination call.”

M. Sue Bergin is an adjunct faculty member in the BYU Honors Program and a writer and editor in American Fork, Utah.

Related Story:

True to Blue

By M. Sue Bergin, ’79

The day after Cecil O. Samuelson was named president of BYU, a friend delivered to Elder Samuelson’s office a round layer cake decorated with white frosting and Cougar-blue piping. On top were written the words Stay True to Your School, with the Y conspicuously fashioned to look just like the Cougar block Y.

“He cut it open, and it was red!” says Sharon G. Samuelson, President Samuelson’s wife.

The friend was Kristen McMain Oaks, wife of apostle Dallin H. Oaks, ’54. With degrees from both the University of Utah and BYU (a doctorate in 1988), Sister Oaks is familiar with the loyalty questions—and jokes—the Samuelsons face. Sister Samuelson, in particular, has been an easy target because of her lifelong passion for the Utes.

“Ever since the announcement, anybody who knows Cec and Sharon has just laughed and thought, What is Sharon going to do? They’re waiting to see how she is going to look in blue,” says family friend Ellis Ivory.

Sister Samuelson confirms that friends are finding the situation exceptional fodder for teasing.

“We’ve been sent red and blue balloons. I’ve gotten red and blue flowers and red and blue cookies,” says Sister Samuelson. And she’s starting to hear the rumors floating around BYU, including one that says the bottom of the Samuelson’s swimming pool brandishes a huge red U.

Just one problem: The Samuelsons don’t have a pool.

Both President and Sister Samuelson want to put to rest any ideas that they can’t or won’t be fully devoted to BYU. “As my husband has said, you love your first child, but you love your second child just as much, and you don’t love the first any less,” says Sister Samuelson.

Former University of Utah president Chase N. Peterson, a longtime colleague of President Samuelson’s, believes the rivalry is due for tempering, and Samuelson might be just the person to accomplish that. “This is an opportunity for further cooperation and joint efforts.”

Peterson has no doubts about his friend’s ability to add a new allegiance: “His loyalty to BYU will be exceeded by no one.”

Samuelson showed that loyalty immediately. Though it was a Saturday and only his third day on the job, President Samuelson caught a last-minute flight to Long Beach, Calif., to cheer on the BYU volleyball team as it competed for the national title.

As for the rest of the family, youngest child Sara will continue her studies at the U, and oldest child Cecil III will stick by his red alma mater. His most pressing concern is not whether his parents will turn true-blue but whether they will hang on to their coveted U of U season tickets.

If not, he says, “I can use them!”

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.