Employment Especialistas

Employment Especialistas

BYU interns lend a hand in Church Employment Resource Centers in Peru and around the world, teaching skills and spreading hope.

By Brittany Karford Rogers (BA ’07) in the Summer 2010 Issue

Photography by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

The developing housing in La Molina Vieja is easy to spot—a distinct line where colorful structures cease to hike up yet another brown, nondescript hillside in Lima, Peru. There are homes in every stage of the metamorphosis of urbanization here, from bamboo walls to wood to painted concrete. There are not, however, a lot of places to eat.

This is a problem.

When the weekend comes, “the women are tired of cooking,” according to Adolfo Aguirre. Sandra Muñoz, his wife, cooks for their family all week and makes empanadas for restaurants down the hill. But the plan they’re cooking up won’t reduce kitchen time—for Muñoz, anyway.

First, though, they are going to run the details past two Spanish-speaking BYU students who are right on schedule.

She makes mouthwatering empanadas. He makes a mean chicken dish. After taking the LDS Self-Employment Workshop from BYU interns Robert Kinghorn and Eric Meldrum, Sandra Munoz and Adolfo Aguirre believe they have what it takes to open a restaurant.

“¡Gringuito!” Muñoz calls out to Robert M. Kinghorn (’10), who dances through her door, stepping around a Chihuahua in a tight blue tank top. At 6-foot-7 Kinghorn bends to engulf her in a hug; most Peruvians are on the 5-foot-5 side of things. His companion, fellow student Eric W. Meldrum (BA ’10), is just a step behind. In white shirts and ties, the two look like a couple of tagless missionaries.

“It’s obviously a natural comparison people make,” Meldrum would explain later, and he and Kinghorn agree they’re on a sort of mini mission—without quite as many rules. They’re here in Peru on a BYU study abroad directed by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and they’re here in La Molina Vieja to talk chicken with Muñoz and Aguirre.

The couple hopes to open a restaurant featuring Aguirre’s signature dish, pollo cilindro. The way Aguirre makes it, he says, “the meat just sweats.”

“We’ve already got a freezer,” Muñoz interrupts, pointing out the big, white deep freeze in the room—one of the few furnishings in the apartment. “We’ve been collecting things.” The curious eyes of children peer out from the kitchen, where plates, dinnerware, blenders—the makings of a restaurant—are stacked about. Muñoz’s mother breaks out platters of pound cake and a chilled liter of Coca-Cola, and Meldrum and Kinghorn are ushered to the dinner table, where Muñoz opens her workshop booklet.

As LDS Employment Resource Services (ERS) interns, Kinghorn and Meldrum have been trained to facilitate the Church’s Self-Employment Workshop. Holding group instruction in the evenings, the pair squeezes in personal meetings, like this one, during the day, teaching basic entrepreneurial skills to as many members of the Church as possible.

Even successful entrepreneurs, like restaurant owner Susana Manrique, attended the students’ workshop to improve their business.

Or, in Muñoz and Aguirre’s case, nonmembers. Muñoz’s mother, a member of the Church, heard two BYU students were coming and referred her daughter straightaway.

“We had this vision of opening a restaurant,” says Muñoz, now two weeks into the workshop. “But they are giving us clarity in carrying out that plan.”

That clarity comes through answering some important questions, and the BYU students’ questions are endless: Who is your competition? Do they serve the same food? Who eats there? From what socioeconomic group are their clients? How can you tell? Is it the way they dress? Are they interested in price or quality? What province are they from? How far will they travel? How much will they pay?

Aguirre and Muñoz have some work to do in identifying their market, but they are undeterred. “The people, right here where we live, go out looking to eat; they exist,” Aguirre says. Everyone here orders pizza or pollo a la brasa, Peru’s ubiquitous rotisserie chicken—“There is nothing else.”

“Then we’re going to find out exactly who they are and what they want,” Kinghorn responds. “And then we’re going to give it to them.”

Better Life

It’s worth asking why two twentysomethings from BYU, who are not business majors and have no professional career experience, are in Peru teaching entrepreneurship. The reason stems back 10 years.

“In the late ’90s the Church was gravely concerned about returned missionaries in developing countries who couldn’t get work,” says Jan Van Orman, BYU’s assistant international vice president at the time.

“There’s more than enough creativity in Peru,” says Napoleon Quispe, director of the Employment Resource Center in Lima. “What Peruvians may lack is confidence that they can be entrepreneurs.” BYU interns, he says, help lower the risk.

A committee was formed to discuss what could be done; Van Orman sat in on behalf of BYU. Many collaborative efforts were drummed up. And in 2000 Church President Gordon B. Hinckley announced a plan to roll out more than 30 additional ERS centers worldwide in the space of a few years. The Church invited BYU to provide students, like Kinghorn and Meldrum, to help.

Young and untethered, well versed in foreign languages, and capable of learning the ERS curriculum, BYU students had great appeal. The university was amenable, provided that students could still advance toward graduation while completing an internship. Van Orman worked with college advisors to patch together coursework the first pair of ERS interns could complete remotely, and in 2001 the ERS internship was born.

“[The BYU students] brought an excitement and a vigor that was contagious,” says Larry D. Stevenson (BA ’78), manager of the ERS center in Provo; Stevenson helped train the first interns. Sent to various locations around the world, the BYU interns taught the ERS Career Workshop primarily to their peers, returned missionaries and other young adults who were eager to benefit from the new Perpetual Education Fund (PEF). With PEFgrants, those RMs could obtain training, and through the Career Workshop, they could find help in job placement; they could better their lives.

“That’s what happens in these workshops,” says Stevenson. “And when you’re involved in seeing that change . . . it both humbles and strengthens you. The BYU students came back knowing the world could be changed.”

“When you’re involved in seeing that change . . . it both humbles and strengthens you. The BYU Students came back knowing the world could be changed.” —Larry Stevenson

Robert Kinghorn helps entrepreneur hopefuls in the Employment Resource Center in Lima, Peru, research everything from microfinancing to the number, sizes, and locations of competitors.

After that first group, BYU students began staffing ERS centers new and old in more than 50 countries, the centers receiving interns on a rotational basis. BYU interns also trained local instructors to teach the course, extending the workshop’s reach further. And while the Church received manpower, BYU received a service-focused study-abroad experience unlike anything else offered at the university.

“It’s not the London Centre,” says Van Orman. “It’s not going with a language professor to spend six weeks studying abroad. It’s being out on your own.”

ERS interns are turned loose; they are the teachers. And “no one learns more than the teacher,” says Spanish and Portuguese professor Christopher C. Lund (BA ’67), who works with ERS interns who are Latin American Studies majors and minors. Several departments have even created courses specifically for ERS interns, such as sociology 445, a class on the sociology of labor markets. “[Students] see how concepts can be applied to the actual experience of the people living there,” says the course’s instructor, Professor Tim B. Heaton (BS ’74).

Open to all majors, the internship’s only absolute requirements are language proficiency and a willingness to serve. To date, 213 sets of BYU ERS interns have helped more than 20,000 people around the world, from Ghana to Mongolia to Chile to Hungary.

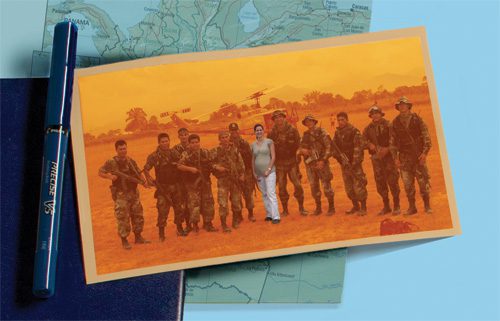

The six students sent out in winter 2010 were assigned a companion and a field of labor, much like receiving a mission call: two female students went to Panama City, Panama; two male students to Manaus, Brazil; and Kinghorn and Meldrum to Lima. But instead of teaching the Career Workshop, Kinghorn and Meldrum are part of the next chapter, the first wave of ERS interns to teach the Self-Employment Workshop exclusively.

Students—and Other Stuff—for Sale

Six ceiling fans merely stir the warm evening air in the La Molina Vieja chapel, where Kinghorn and Meldrum stand between a whiteboard and 23 workshop participants. The students’ collared shirts, crisp this morning, have wilted. Nevertheless, Meldrum is putting Kinghorn up for sale.

“Robert is my product,” he leads out. “It has an education, it speaks Spanish, . . . it’s so-so at dancing. And I’m going to sell him to the chicas. But who is my market?”

“Girls!”

“Women!”

The answers come from all over the room, predominantly from the female contingent.

“Widows—don’t forget widows!”

“Good,” Meldrum manages through a smile. “Where is my client located?”

Institute, university, even the Young Women organization are shouted out.

Meldrum holds up his hand in warning. “You can’t assume the girls want this thing,” he cautions. To know what girls want, you have to do an analysis of the market. “You have to go on dates!”

A graduate of the workshop, Carlos Tito refurbishes fuel-injector pumps. “I feel the Lord has inspired this workshop,” he says, “from His prophet down to the university students”Meldrum calls on a single young woman to describe her ideal man. Blushing, she elaborates: strong, intelligent, returned missionary.

“This is exactly what you’re going to do in your homework this week,” Meldrum announces to the class. “You’re going to identify your client and ask them what they want. You’re going to conduct a survey.”

Fresh out of college herself, Sheila Vela team-taught the Self-Employment Workshop with the BYU interns and will continue teaching the workshop when they leave. “To see how they give… makes a person want to give,” she says.

Doing homework, the BYU students say, differentiates those who ultimately have success. “They either develop more confidence in their plan or they realize their business idea was flawed from the start,” says Meldrum. “In both cases we’ve done them a service.”

To give participants time to be thorough, the BYU duo teaches the workshop over the course of five weeks. In that time, they cover the workshop’s four cornerstones—business idea, market analysis, marketing strategy, and financial analysis—taking the workshop to different groups on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday nights in ward and stake meetinghouses all over Lima.

The workshop garners the best attendance at night, but in the case of an exception, the students are on hand every morning at the ERS center in San Isidro, Lima’s financial district—a three-hour commute away for some.

“I left my house at 7 to get here by 10 this morning,” Eudosia Yarleque says at the center one morning, “because Eric and Robert invited me to come.” She commuted from the Villa El Salvador district of Lima; getting anywhere in this city of 9 million takes time. Yarleque had been attending one of the evening workshops, but the late-night commute put her at her home bus stop at midnight in a bad part of town.

From her purse, Yarleque draws out a handwritten document—her first survey. She wants to sell carwash supplies, yet she is not just here for herself.

As the Villa El Salvador Stake employment specialist, she estimates that half of the members in the stake own a small business. Self-employment, she says, is imminent for many Peruvians. “Here in Peru, they only accept in employment those up to [age] 40. The young are stronger and quicker. That’s who gets hired.”

“There is no government safety net,” Meldrum adds. “Here, people rely on their families to take care of them as they age.”

Upon their arrival, Kinghorn and Meldrum were briefed on the Peruvian economy by Napoleon Quispe, director of the ERS center in San Isidro. Quispe has navigated the rungs of the economic structure here: he grew up in Quillabamba, a small town near Machu Picchu, without shoes to wear to school; today he has his own swimming pool. He says the two BYU students are now well educated on the subject of stratification and mobility in Peru.

“For every 10 companies that are created in Peru, only one will survive the first two years,” says Kinghorn. The purpose of the workshop is to lower that risk.

“It’s overwhelming, the response the students have received,” Quispe adds. “I thought it was a miracle. Right now, we teach as many as six [self-employment] workshops a week.” Simply by arriving, Kinghorn and Meldrum doubled his center’s full-time manpower. “When they leave, it will probably go down to one.”

Strutting Their Stuff

Humberto “the Chef” Lozada and Daniel Acevedo show off their inventory of cleaning supplies to their BYU instructors. The pair more than tripled their sales while taking the Self-Employment Workshop.

Humberto Lozada’s garage reeks of roses and pine. Inside, his inventory of cleaning agents and insecticides lines the walls, caging in a derelict, blue ’69 Dodge Dart.

“I can kill cockroaches in 10 seconds,” he asserts.

“He is the chef,” Lozada’s business partner, Daniel Acevedo, affirms.

The two, part of Kinghorn and Meldrum’s first workshop group, brew and sell cleaning supplies, making their products in Lozada’s yard. And in two and a half months’ time, business has more than tripled. Their success, they say, came as they took the Self-Employment Workshop. “It gives results,” Acevedo says.

Soaking up everything Kinghorn and Meldrum taught them, Acevedo and Lozada focused on making the competition’s weaknesses into their strengths. They also learned how to present their business—fortuitously in the same week that Acevedo had a meeting with Cañetana, a major market distributor. It was four on one: Acevedo faced the boss and three salesmen.

“I presented just like I had presented in class,” says Acevedo. “I went straight to the point. When I made my power statement, . . . they sat there with their jaws open.”

Cañetana purchased 1,000 Peruvian nuevos soles of product right then and there, immediately doubling the combined sales Acevedo made the previous month. And the cockroach killers strutted into class the next week.

“They walked in with smirks on their faces,” says Kinghorn. “They said, ‘Hey, guess what? It worked.’”

It gave the BYU students confidence that their instruction was valuable.

Acevedo and Lozada, however, are but one of the students’ success stories.

Eva Rose and Napoleon Garces started from scratch in the workshop, with nothing more than ideas. Garces is now the sole distributor of a NASA-developed water-saving attachment, and he’s employing members of the church.

Across town, in an affluent niche of housing, Eva Fleischman Rose and Napoleon Garcés have a doorman and a maid—and a passion for bridge (it’s how they met). Garcés moved from his native Ecuador to marry Rose; her Jewish family had put down roots in Lima after fleeing Germany with falsified passports in 1939.

Neither Rose nor Garcés is a member of the Church, but in their living room, they explain how they ended up in the LDS Self-Employment Workshop. Rose, who dabbles in real estate, had lined up housing for the BYU students in Lima and took interest in their purpose here. Garcés tagged along to the workshop.

“It was incredible,” Garcés says.

A civil engineer who specializes in water treatment, he’d heard of BYU before—“In engineering BYU is very well known,” he says. The workshop got him thinking. He’d recently been offered the right to be the sole Peruvian distributor of water-saving faucet attachments innovated by NASA. Initially, he thought nothing of it. “I’m an engineer; I had no experience running a business,” says Garcés.

The workshop changed his mind.

Week by week, he meticulously went through the workshop’s prescribed course of action. “His financial analysis was mind-blowing,” says Meldrum. Garcés jumps at this cue to unroll a poster projecting his first-year expenses. Three of Garcés’ fellow workshop participants, the students add, asked for a copy.

Now, just one and a half months after taking the workshop, Garcés’ store is slated to open. And when it came time to hire employees, the first-time store owner knew where to turn.

“He hired two members of the Church from the ERS center in San Isidro,” Kinghorn says proudly. “That’s two jobs that weren’t there before.”

Changing Minds, Changing Lives

In stark contrast to Garcés and Rose’s part of town is the squatter town of Manchay, toward which the students are traveling in a hatchback taxi. The ride is getting rougher, which tells them they’re getting closer; the road has more potholes the further south they drive.

“There he is,” Meldrum says, and the taxista halts in the middle of the road, eliciting blares from surrounding drivers. The students wave Miguel Aulestia over from a street corner, and he squeezes in to accompany them from here; it is unwise for foreigners, well dressed at that, to walk in Manchay alone at dark. Aulestia will escort them to the home of his sister, Lucy Nole.

The students use something akin to the food pyramid to describe the distribution of wealth in Peru: The tiny triangle at the top represents the wealthiest, level A. Subsequent strips represent successively lower classes. Level E, the base of the pyramid, is the largest—those with dirt floors and without running water. Nole falls in what the students call level D.

Her jewelry business hasn’t taken off yet, Lucy Nole explains to her BYU “angels.” Still, she says, the workshop has given her confidence that she can change her situation.

Reaching their drop-off point, the party walks up a dusty side street until the students come to a familiar door.

Peering out from a barred window, Nole smiles, calling out, “My angels, my angels!” as she scurries out to meet them. She took the Self-Employment Workshop in February, hoping to launch her handmade-jewelry business; the students are back to see how things are going—and to buy some of her wares for moms and girlfriends.

“I really liked the classes,” Nole offers, almost preemptively, as they enter the apartment. She has little capital for supplies, and with her new job, she hasn’t had much time for her jewelry. She’s now an elementary school teacher in Manchay. “If I leave my work, I can keep going with my business. They are both resources. I am always looking for resources.”

Money has been a lifelong struggle, Nole, 53, says. She still dreams of affording college or owning a home someday.

“BYU interns get in and work at the ground level with families and individuals who are perhaps in the most tender and trying times of their lives.” —Richard Ebert

“It’s our dream that you can have success,” Kinghorn tells her, his eyes welling, “that you can find a way to succeed.”

Nole nods. “I have to fight. It’s important to me to support my family.” Blinking rapidly, she can no longer dam her wet eyes. “Thank you for traveling so far to share your knowledge with us,” she says, tears escaping down her cheeks, “for sharing your time and resources.”

“It has been worth every penny,” says Kinghorn. He and all ERS interns pay for their experience, abetted by funds from university donors—primarily two generous families. Faculty have also pitched in.

Stephen W. Gibson (BS ’66), associate teaching professor and entrepreneur in residence at BYU’s Melvin J. Ballard Center for Economic Self-Reliance, has donated to a fund that has helped finance the ERS internship and other like initiatives. His research focuses on moving individuals in developing countries from poverty to prosperity; he believes programs like this create hope.

“Groups go to third-world countries and build latrines,” Gibson explains, “but I see pictures of students doing all the work and the recipients watching, and that’s the saddest thing. These ERS interns are actually changing the lives of the recipients by changing the mindsets of the recipients. Changing the way someone thinks and acts—now that’s life changing.”

Though Nole’s jewelry business has yet to be successful, she believes she is changed. “Now I am confident; I am better guided,” she says. “I know how to do a basic market analysis. My mind is more open to different ways of doing things. God has given us a lot of talents, and we can discover and develop them. I can apply what I’ve learned to anything.”

Kinghorn and Meldrum say their experience as ERS interns has shown them how to make a difference. “Entrepreneurship drives economic growth,” says Meldrum. “Every little business that starts, as long as it’s growing, is providing jobs. . . . And someone successful in running a business now has confidence. They can teach others, and that changes the culture. It has a real impact.”

That impact extends through the Church as well, says Richard W. Ebert Jr. (BS ’71), the director of LDS Employment Resource Services. “Until you are self-sufficient financially, your ability to participate in the gospel and serve in Church callings is severely limited. BYU interns get in and work at the ground level with families and individuals who are perhaps in the most tender and trying times of their lives. They provide individuals with skills they can . . . then share with their children. It’s a benefit that ripples throughout their own lives and possibly through generations.”

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.