He was coming. People in the teeming crowds craned their necks to see the most feared and admired man in the Ottoman Empire—Süleyman the Magnificent. Those lucky enough to catch a glimpse of the sultan saw a tall, trim man dressed in heavy silk robes and a turban adorned with flashing diamonds and a spray of peacock feathers. His entourage was equally fantastic. The sultan always traveled with great ceremony, even into battle. But today the sultan was not leading his troops to war—he was going to Friday prayers. Once the sultan arrived in the lofty, holy interior of the Aya Sofya mosque, however, heraldry and fanfare were replaced by reverence as the sultan knelt in pious devotion, his knees sinking into the plush Turkish carpets.1

The Hagia Sophia Christian Church was already more than 900 years old when the Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453 and converted the building into the Aya Sofya Islamic mosque.

“The Ottomans were such an interesting mix,” says Diana L. Turnbow, ’92, assistant curator for BYU‘s Museum of Art. “They had the fiercest and most disciplined army in the world, but they also loved flowers and running water; they cultivated tulips and ate delicacies, like apricots stuffed with walnuts and cream.”

At their peak, the Ottomans expanded their empire to include Tunis, Cairo, Jerusalem, Damascus, Mecca, Baghdad, Constantinople, Athens, and Budapest; their cultural influence, however, extended far beyond these borders. The 600-year reign of the Ottomans left an indelible imprint on the world, influencing modern religion, music, art, architecture, and politics. And this fall the empire’s reach extends to Provo as the Museum of Art presents Empire of the Sultans: Ottoman Art from the Khalili Collection. The exhibit, which opened Aug. 17 and runs through Jan. 20, 2003, demonstrates the power, majesty, and piety of the Ottoman Empire through silks, lavishly decorated swords, illuminated manuscripts, carpets, scientific instruments, ceramics, and more.

The Ottoman Age

Despite their later grandeur, the Ottomans started as a small tribe of Islamic Turks in northwestern Anatolia (present-day Turkey) in the late 13th century. Under the leadership of Osman and then his son Orhan, they expanded into the surrounding Christian settlements of the Byzantine Empire. By the mid-1300s, the Ottomans controlled much of northwestern Anatolia, and over the next century they became the terror of the countryside, conquering Macedonia, Bulgaria, parts of Greece, and more of Anatolia. “The Ottomans had a very effective army,” says Daniel C. Peterson, ’77, associate professor of Asian and Near Eastern languages at BYU. “If you were a tiny Balkan state, you didn’t want to hear that the Ottomans were coming your way, because you didn’t stand much of a chance. Surrender was usually the best option—and they would often give you very good terms if you gave up without a fight.”

In early April of 1453, the 21-year-old Ottoman sultan, Mehmed II, led his army to the walls of Constantinople, the faltering capital of the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantines, who ruled the eastern half of the Roman Empire after it split in a.d. 395, had controlled Constantinople for more than 1,000 years. Mehmed’s siege of the city lasted just over seven weeks; the last, tired Byzantine legions defended their dilapidated city from behind the massive walls, but they were no match for the young, impetuous sultan and his army of some 100,000 battle-hardened soldiers.

Mehmed II attacked the city shortly after midnight on May 29. As the first rays of dawn slipped over the ancient walls, so did the Ottoman troops. The city itself had diminished considerably from its former grandeur, but the sultan knew that his victory at Constantinople, the final bastion of Christendom in southeastern Europe, was more than just another conquest. It signaled a new age—the Ottoman age. Entering the still-smoldering city in the afternoon, Mehmed the Conqueror rode through the charred streets to Hagia Sophia, the revered Byzantine church, where he stood under the magnificent dome and ordered an imam to recite the Islamic invocation.2 Thus, Hagia Sophia, the Christian church, became the Aya Sofya mosque, and Constantinople—eventually known as Istanbul—became the new capital of the Ottoman Empire.

Süleyman’s Empire

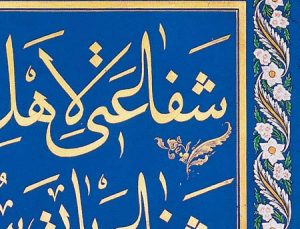

Panel of Du’a, detail, early 19th century. Many later sultans, such as Mahmud II, who created this panel, were accomplished calligraphers.

Süleyman the Magnificent was the longest reigning and is the most well-known of the 36 Ottoman sultans. By the time he came to the throne in 1520 at age 25, his empire sat astride three continents—Asia, Africa, and Europe—and was the envy of contemporary European monarchs, including Frances I of France, Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire, and Elizabeth I of England. “We talk about the Elizabethan England like it was this vast thing,” says Peterson. “Well, it wasn’t. It was this little island off the coast of Europe, and Elizabeth didn’t even securely own the whole thing—Scotland was dubious and Wales was unstable. So she had part of an island. But then you look at Süleyman’s realm. It was vast in comparison.”

Iznik Dish, detail, ca. 1530-50. This dish, like many produced at Iznik, the imperial kiln, imitated Ming dynasty porcelains.

During his reign, Süleyman extended his sprawling empire to include Hungary, Iraq, and most of North Africa. Süleyman’s domain claimed well more than half of the Mediterranean’s shoreline, nearly circled the Black Sea, bordered the Red Sea, and touched the Persian Gulf.

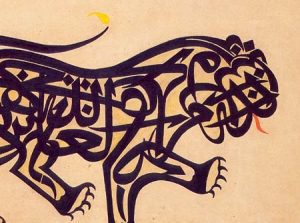

Calligraphic Lion, detail, 1913. The inscriptions that form this lion are invocations to ‘Ali, the fourth leader of Islam.

The Ottomans believed that Süleyman was “the shadow of God on Earth,” the leader and protector of Islam. Yet, religiously speaking, the Ottomans ruled with a fairly light hand and even fostered religious diversity.

“By medieval standards, this tolerance was unheard of,” says Peterson. “If you were a Muslim in Europe, you were toast! And Jews suffered awful persecution at the hands of the Christians.” However, when the Jews were expelled from Spain during the Reconquista in 1492, the Ottomans welcomed about 100,000 Jews into the empire.

Usak Carpet, detail, ca. 1450_1550. Usak, in western Anatolia, sometimes produced carpets for the sultan’s mosques.

Süleyman’s conquests brought not only diversity to the empire, but also overwhelming riches, which accumulated at the Seraglio, the sultan’s private residence. While paying for the paved roads and aqueducts throughout the empire, these tributes and taxes also provided the sumptuous meals served at the sultan’s frequent dinner parties. Lasting 50 courses, these delectable feasts included sherbet refrigerated with snow that had been scooped from Mount Olympus’ peaks and packed in felt bags, which were carried by mules to a seaport and shipped 70 miles to Istanbul.3

As the most prominent member of the Islamic community, however, the sultan also commissioned magnificent mosque complexes, which often included schools, hospitals, and soup kitchens. Characterized by huge, elegant domes, these mosques “really took architecture to the celestial level,” says Cynthia Finlayson, a BYU assistant professor of art history. “They allowed the worshippers to come into the building and focus on their eternal potential.”

From high in his palace, Süleyman could survey his capital—the skyline outlined with the smooth curving domes of his many mosques and sharpened by the silhouettes of delicate tapered minarets, the sounds of the marketplace mingling with the dissonant tones of the muezzins’ rich voices calling the faithful to prayer. Little did Süleyman know that his empire would begin to change in just one generation.

Decadence and Decline

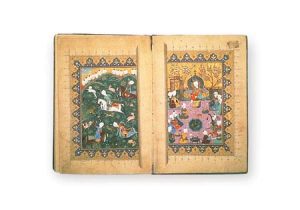

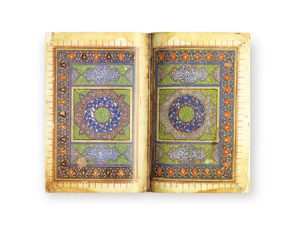

Sa’Di’s Bustan, 1530. This volume is an illuminated copy of a book by Sa’ki, a revered medieval Islamic poet.

There was no subtle gradation between the military and administrative brilliance of Süleyman and the incompetence of his successors. Luxury became the purpose instead of the result of the empire as Süleyman’s own son, Selim II, began the trend of abandoning his political responsibilities in favor of the indulgent world of the Seraglio. “In fact,” Peterson notes, “it is a tribute to the earlier leaders that the empire lasted as long as it did once it fell into the hands of the later sultans.”

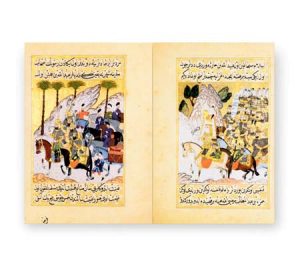

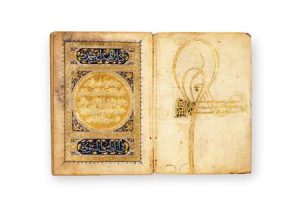

Arabic Text on “Prophetic Medicine,” 1520. This volume was produced for Suleyman the Magnificent, whose imperial monogram is on the right-hand page above.

For example, while the edges of the empire were crumbling in the early 1700s, Sultan Ahmed III indulged in moonlit tulip fêtes in his extensive and expensive tulip gardens, requiring his bejeweled guests to dress in colors that harmonized with the blooms.

As expanding European powers nibbled off the frontiers of the empire, the Ottomans also began to lose the economic race with Europe. Earlier, the Ottomans had produced technology and imported it to Europe, says Glen M. Cooper, ’88, a BYU assistant research professor of Graeco-Arabic studies. “However, when the Ottomans reached their plateau, Europe went through the enlightenment, and the industrial revolution and the scientific revolution just blew past them.”

Single-Volume Kur’an, ca. 1470. this Kur’an was created for a dignitary in court of Mehmed II, the sultan who conquered Constantinople.

Over time the Ottoman Empire became a pawn for European states as they tried to maintain the balance of power on their continent. The Ottomans also dealt with internal instability, and the Young Turks, a revolutionary group tired of ineffective leadership, took power in the early 1900s, reorganizing the government to limit the sultan’s authority. Shortly thereafter, the Young Turks led a weakened empire into World War I as Germany’s ally. The Ottoman Empire was officially dissolved at the war’s end as the Western powers carved up its territory, leaving only modern-day Turkey as the heir of the once-expansive nation.

A Continuing Influence

The empire’s later contemporaries were not surprised to see it die, but they may not have realized the effects of the Ottomans on the modern world. Most Westerners, for instance, do not know that their coffee, shish kebabs, and tulips (which were exported to the Netherlands in the 1500s) are all testaments to the continuing influence of the Ottomans. Many homes contain other remnants of the empire’s legacies: Turkish carpets, overstuffed sofas, divans, and ottomans, all edged with fringe and tassels.

In addition, percussion instruments, including triangles, cymbals, and kettle drums, were used by the Janissaries, an elite Ottoman military group, to intimidate their enemies as the Janissaries marched into battle. Beginning in the 1700s, however, the Janissaries’ music became the rage in Europe, and percussion instruments in an orchestra became known as “Turkish music.” The sounds that once elicited terror thrilled audiences in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Haydn’s Military Symphony, and Rossini’s William Tell Overture.4

The Ottomans also played a great role in more significant cultural changes. For example, in the 1500s the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, wanted to eliminate the Lutheran princes. However, the Ottomans were such a threat to his empire from the south that he didn’t dare send all of his armies to fight the Protestants. “Which means,” Peterson says, “the Ottomans may have saved the Protestant Reformation.”

Of course, the Ottoman Empire also had a significant effect on another religion—Islam. “They really did change the flavor of Islam in many ways. Coming from a backdrop of eastern Asia, they displaced the Arabs as the leaders of the Islamic world,” says Peterson.

In addition, Cooper says, “the empire provided an opportunity for the flourishing of Islamic politics, art, and architecture.”

Ottoman architecture in Istanbul, typified by mosques with large domes and open spaces, became a prevalent style in later Islamic architecture. Finlayson explains, “The openness of the mosque is a reaction against Orthodox Christian architecture, which separated the priesthood from the common people. Muslims believe that no one should be between the worshipper and God; the openness of the mosque is symbolic of the worshipper’s direct relationship with God and the spiritual equality of all humankind.”

The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire also affected Islam. “The fall of the Ottoman Empire was a shocking blow to the Islamic world,” says Cooper. “When the sultanate was discontinued, the Muslims were left without a central Islamic political authority.”

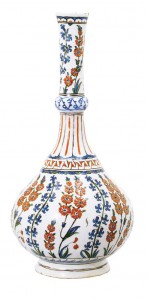

Iiznik Flask, ca. 1560-80. In addition to dishes, jars and flasks, Isnik potters produced tiles for royal places and mosques.

Despite the significant legacies of the Ottoman Empire, Turnbow says that not many people are well-versed in the history of the 600-year dynasty. “We are familiar with the ancient Near East because we read the scriptures, and current events draw us to the modern Near East. But between the ancient world and the modern world, we have a knowledge gap, and we don’t really know what happened during that time—the Ottoman Empire is part of what happened.” Turnbow, however, hopes that the Empire of the Sultans exhibition will help fill in the gap. “I hope this exhibition will help people learn more about the Ottomans and realize that this rich culture it is not so far removed from our own heritage.”

Liza Richards is an editor for ADP Benefit Services in Salt Lake City.

Notes

1. Noel Barber, The Lords of the Golden Horn: From Suleiman the Magnificent to Kamal Ataturk (London: MacMillan, 1973), pp. 24–28.

2. Bernard Lewis, Istanbul and the Civilization of the Ottoman Empire (Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963), p. 6.

3. Barber, p. 28–29.

4. Donald Quataert, The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922 (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2000), pp. 8–9.