In a light-filled BYU gallery, a special exhibition reveals a little-known and remarkable heritage of learning and faith.

In a light-filled BYU gallery, a special exhibition reveals a little-known and remarkable heritage of learning and faith.

In a light-filled BYU gallery, a special exhibition reveals a little-known and remarkable heritage of learning and faith.

Across the eastern face of the Joseph F. Smith Building runs a 200-foot curved glass curtain. This curtain encloses a grand gallery on the second and third floors. And in this gallery, a permanent multimedia exhi-bition opened its doors in fall 2008. The exhibition is titled Education in Zion.

For the dozens of us—mainly BYU students and recent graduates—who worked to develop the exhibition between 2000 and 2008, it has been like a secret passageway to a remarkable treasure. I think of it as an inheritance that we did not know was ours. We discovered the stories of the people who founded this school and who, under the guidance of God, created here a kind of education that is different from anything the world has to offer.

Education in the kingdom of God is unique because, first, it is an education of the whole soul. Second, to the degree that we are living as the gospel requires, it takes place in an environment of learning in which we are unwilling to leave others behind. Those we help, help others—our own posterity among them. We are drawn together; we become united, a Zion people. Fundamentally, education in the kingdom of God is different because it operates on the Zion principle of love.

This Zion tradition of learning goes back to Joseph Smith. His was truly an education of the whole soul, divinely orchestrated. Heavenly teachers were his instructors and models. Joseph and his successors sought diligently to bring a similar whole-soul education to as many Latter-day Saints as possible. They established priesthood quorums, auxiliaries, community schools, stake academies, colleges, a university, and eventually seminaries and institutes. They kept at the work even in desperately impoverished circumstances. They understood very clearly the urgency Elder Jeffrey R. Holland (BS ’65) expressed when he presided at BYU in 1981. “This Church,” he said, paraphrasing Joe J. Christensen (BA ’53), then the president of the MTC, “is always only one generation away from extinction. . . . All we would have to do . . . to destroy this work is stop teaching our children for one generation” (“That Our Children May Know,” Campus Education Week devotional address, Aug. 25, 1981, p. 4). It was not primarily for themselves but for the children of the future, for Zion, that these visionary leaders and their faithful associates worked so hard.

Likeness of and words from such exemplary teachers as Jesus Christ, Joseph Smith, and Karl G. Maeser remind visitors to Education in Zion of who the spiritual and secular intertwine in Church education. Much of the exhibition was crafted by more than 60 students–researchers, writers, designers, curators, artists, and videographers.

There’s almost nothing we can name that has absorbed as much of the latter-day prophets’ attention, energy, and care as the education of this people. You may have thought that you came to this university primarily to take a series of courses, obtain a degree, and then leave learning behind. The truth is that God desires the flourishing of your whole soul for the glories He has in mind for you, including an eternal family with children who will shine as jewels in your crown, and that is why He intends to bless you, if you will exert yourself, with a soul-stretching education.

The inheritance I have described is yours to claim, if you desire. In the pages that follow, you can learn some of the stories of those who bequeath it to you, and the next time you come to BYU you can visit Education in Zion to learn more.

—C. Terry Warner (BA ’63)

Terry Warner is a professor emeritus of philosophy and directed the team that created the Education in Zion exhibition. The text above is adapted from a devotional given Nov. 11, 2008, in the Marriott Center.

As important as education was to the early Saints, resources were scarce in the swamps of Nauvoo. It was more imperative to build homes for families than classrooms for students, so the entire community became their schoolhouse.

One wall of the exhibition (above) is covered by a map of the early LDS community and shows more than 80 houses and other buildings that were used for classes, cultural events, lectures, vocational instruction, and other educational endeavors. “It seems as if almost every building, every possible facility in the city of Nauvoo, was used for educational pursuits,” says Matt Larson (’09), who helped design and produce the exhibition for three years.

Larson, an industrial design major, created computer renderings for the exhibition design and designed furniture that would help set the tone. As he waited for paint or glue to dry while setting up portions of the exhibition, Larson found spare moments to read the stories of many of the pioneers of education, including the early Nauvoo Saints.

At the map of Nauvoo one day, a researcher pointed out to him various houses where the Prophet Joseph Smith learned German or where other Saints took violin lessons. “They worked together as a Zion community to truly teach each other,” Larson says, adding that a similar spirit of cooperation and service pervades BYU today. “This university is very much set up in a way that we are encouraged not just to learn for selfish reasons . . . but to be able to learn for the purpose of serving others.”

—Erica J. Teichert (’10)

In the winter of 1850, Apostle George Albert Smith traveled to Southern Utah to help establish Latter-day Saint settlements in St. George and the surrounding areas. Even in the chill of a Utah winter, Smith was determined not to let meager facilities keep him from educating the young people. “At nighttime he would sit around the campfire with some of the youth from the settlement and teach them grammar lessons,” says Nathan R. Ricks (BA ’04), a student researcher for Education in Zion. “He talked in his journals about the joy that it gave him and the rewarding thing that it was to be able to sit together and learn.”

After the long trek west to Utah, Church leaders were determined to provide wholesome educational opportunities for the Saints. Faded sepia-toned photographs in the exhibition show throngs of students posing outside school buildings—often just any available structure. In one community, the lack of a schoolhouse brought students to a former tannery for their education.

“The Saints tried to do anything and everything that they could do to increase their knowledge of the world around them,” says Ricks, who worked on the exhibition for a summer before he began a graduate program in history at BYU. “They met together on a regular basis for all kinds of educative efforts. They’d meet together with returned missionaries for foreign languages. The Saints really did love education, continuing to learn, and perfecting oneself as part of that road to becoming like God.”

—Sarah E. Crane (’09)

During the late 1800s, only the students were poorer than BYU, which was running on little to no money. The average class cost $2 or $3, the equivalent of about $45 today, yet the cost was too much of a financial burden for many early students.

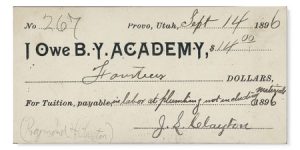

“We found envelopes that were just packed full of IOU slips from the students for their tuition,” says Laura Van Duker (’10), a curatorial assistant for the exhibition. “They were willing to sacrifice whatever they could for their education.” BYU often accepted produce, jewelry, lumber, or use of a family carriage in lieu of tuition. The exhibition includes reproductions of IOU slips (above) as well as of notes acknowledging payment in kind for tuition.

Van Duker, a psychology major, was touched by the relationships she found between the university and its pupils. “The display is just the tip of the iceberg,” she says. For one year, Van Duker scanned images and documents and found artifacts that helped tell the story of BYU education. After seeing the sacrifices many made to attend the school, Van Duker saw BYU, and her own education, in a different light. “The school isn’t just catering to us. We make up the school. We make it what it is.”

—Erica J. Teichert (’10)

John A. Widtsoe and his wife lost four children before the children reached adulthood. In 1927 one of their three remaining children died at age 24 of pneumonia. After losing so many other children, this son’s death was especially difficult for Elder Widtsoe, who found it hard to do his work as an Apostle.

Just two months after his son passed away, Elder Widtsoe was scheduled to be the keynote speaker at the annual seminary and institute summer teaching convention. Elder Widtsoe had reported days when he had trouble wanting to get out of bed, let alone teach and socialize. “He still spent five weeks in a tent at Aspen Grove,” says Brett D. Dowdle (BA ’05), who stumbled upon the story as he spent hours in various archives researching seminaries and institutes for Education in Zion.

Not only did Elder Widtsoe attend and lecture, but he conscientiously spent time with one seminary teacher in particular, John M. Whitaker, who was ill with ulcers and couldn’t attend meetings. The Apostle hiked to Whitaker’s tent each afternoon, sat on his cot, talked to him about the gospel, and provided great comfort for him. “He saw the importance of what these conventions were doing,” Dowdle says. “[So much that] he would set aside his own grief.” A black-and-white picture of that 1927 summer convention—with Elder Widtsoe sporting suspenders, glasses, and a distinguished goatee—is included in a display about efforts to train teachers. Another display pays tribute to Whitaker, one of the first seminary teachers.

“Sacrifice is the overriding principle that’s impressed me throughout this exhibition,” says Dowdle, whose research took him to BYU special collections, Church archives, and University of Utah special collections. “Faculty and students have given so much more for this university than I gave for my education.”

—Amanda Bagley Lewis (’09)

To date, there have been only 17 honorary fellows in the Acoustical Society of America. Thomas Edison was the first. Harvey Fletcher (BS 1907), who taught physics at BYU, was the second.

As a graduate student at the University of Chicago, Fletcher collaborated with professor Robert Millikan on groundbreaking work on the charge of electrons, which eventually helped Millikan earn a Nobel Prize in Physics. Among Fletcher’s most famous inventions are electronic hearing aids, the audiometer, and stereophonic sound. But later in his life he was especially passionate about one project in particular: electing his wife to be the National Mother of the Year.

His efforts to honor his wife stood out to Vanessa Dowdle Stanfill (BA ’06), a curator for Education in Zion, as she studied Fletcher’s life. Lorena Chipman Fletcher was elected the 1965 National Mother of the Year. “He was so proud,” says Stanfill. “He was one of the most renowned and acclaimed acoustical physicists of his day, and yet he was the most humble, loving, normal person.”

Although Fletcher is not in the exhibition at present, some of the displays will rotate, and Fletcher is slated for inclusion in a future display. Stanfill says Fletcher was a great role model. “He was a father and a servant and a disciple and a genius—and to him, [genius] was always on the side. He had all his priorities in order.”

—Amanda Bagley Lewis (’09)

LETTERS THROUGH THE WAR

LETTERS THROUGH THE WAR

Beneath official military insignia, neat penmanship covers sheets of loose-leafed paper, yellowed from the years. Carefully typed pages carry responses. The correspondence between chemistry professor Joseph K. Nicholes (BS 1916) and his former students serving in World War II reveals relationships that were familiar, warm. “I read through a lot of letters from his students. . . . He cared so much about each student,” says Elizabeth Vernon (’10), a student researcher on the project. Vernon was captivated by the time and attention Nicholes gave to his students. “A lot of his students went off to war. When they would write, he would write back to every single one.”

A graduate of Brigham Young High School, Nicholes taught at what is now Dixie State College and spent his summer breaks at Brigham Young Academy pursuing a bachelor’s degree in math, chemistry, and physics. Later, as chair of BYU’s Chemistry Department from 1945 to 1955, Nicholes forged the program into one of the strongest on campus. A display in the exhibition highlights his contributions to BYU.

Many of the architects of BYU’s foundation of excellence are the early educators who helped build the university from the ground up. “It was incredibly interesting just to see, first of all, how dedicated they were to teaching and to the university,” says Vernon, an education major. “Some stories were really touching. We didn’t get to put in everything that we learned about, but you got to see what good people they were.”

—Sarah E. Crane (’09)

Church history lessons don’t generally say much about Don Carlos Smith, the youngest of the Smith brothers. That might be in part because he was only 25 when he died in Nauvoo in 1841, but Smith and his involvement with the Church’s first printing press stood out to Sienna Woolley Weber (BA ’07). A student researcher for Education in Zion, Weber spent more than three years researching and writing about early Church education efforts.

In 1838 the Church acquired its third printing press—the previous two having been destroyed—and in the town of Far West, Mo., Don Carlos Smith, as Church printer, set up the print shop. “He was so very passionate about it,” Weber says. A wall in the exhibition tells the story of this and other early Church presses, which printed newspapers, scriptures, and missionary tracts.

During the tumult in Missouri, Smith buried the press to protect it from a mob. He later returned with others, unearthed the printing press, and hauled it to Nauvoo, where it was placed in one of the few enclosures available—a cellar—so the printing could continue. In that cellar Smith printed the Times and Seasons and Wasp newspapers. The room had a natural spring coming up out of the floor, exacerbating the already humid, disease-prone conditions. Eventually the poor conditions in the pressroom, in addition to his efforts to help the sick in Nauvoo, caused Smith to become ill and die. “He gave his life in order to print for the Church,” Weber says.

—Amanda Bagley Lewis (’09)

INFO: The Education in Zion exhibition is under the direction of the Harold B. Lee Library and is located on the east side of the Joseph F. Smith Building. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. on weekdays, with extended hours until 9 p.m. on Mondays. It is closed for devotionals and forums and on weekends. For more information call 801-422-6519.

Experience the Education in Zion exhibition online by visiting educationinzion.byu.edu.

FEEDBACK:Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.