That anything survives in a desert is remarkable. But when blossoms emerge from bare sand–and one appreciates the exposed tenderness of new leaves, the struggling energy of roots, and the ingenuity of seed–desert wildflowers appear as unexpected miracles on an empty landscape.

In southern Utah, wildflowers group themselves spontaneously on roadway medians and corners of red rock. From the freeway, the blooms are like fractured pieces of an English countryside scattered across a rocky wasteland. “Even if they weren’t beautiful, wouldn’t it be interesting to think, ‘How did these plants survive here all these thousands of years?’ ” says Kimball Harper, a BYU botany professor and an expert on Utah native plants.

“Nature abhors the vacuum,” he explains, “and she will put some living thing on that surface no matter how nasty it is or how luxuriant it is.”

Harper, who has spent 36 years studying Utah flora, personifies native plants with adjectives we expect to hear in reference to humans, terms that describe cowboy types, pioneer stock. Desert plants are not greenhouse sprouts that can be tended or manipulated, he says. They are gritty survivors. He struggles to learn more about these unique and remarkable plants, at the same time mourning that many of them face almost certain extinction.

On a tour of southern Utah wildflower sites to acquaint a group with his research, Harper quickly nods the names of the abundant roadside wildflowers as he drives by the jagged red spikes of Indian paintbrush, stands of purple phacelia, and other weeds clamoring for attention. Rather than stopping to celebrate their abundance, he takes our group farther south, seemingly away from anything green.

When the car finally stops, it is parked at the edge of a dark mound of soil, one that is mostly bare except for a few thorned bushes, small plants, and a thinly worn carpet of mosses and lichens. Harper and post-doctoral student Renee Van Buren start up a slope on foot, watching the ground as they walk, and stop midway to examine the blooms of a small white poppy.

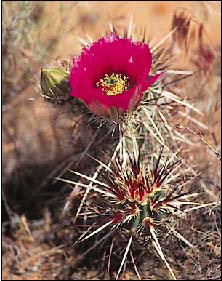

Spines of the desert prickly pear cactus reflect heat, keeping the plant cool even in extreme temperatures.

It is our first introduction to the Utah Dwarf bear-poppy, a small plant that seems rather solitary here on a hill that overlooks rushing interstate traffic and the growing town of Bloomington, just outside of St. George.

“This is the small bear-poppy, so called because its leaves look like giant bear paws,” Harper says. The poppy, he explains, has a complex life cycle and environmental needs that make it unique.

“This species is out of place here. It doesn’t behave like any other species in the state, it doesn’t germinate like they do, and its life history is different. It’s just a species that is residual from another time and place. And there are no others anywhere else on earth.”

Harper and Van Buren have a medical discussion about the poppy’s health problems and what has been a particularly bad year for the species.

“We have monitored this species individual by individual for almost 10 years. During that time, we’ve had some of the driest, most hostile years on record, and the species did fine,” says Harper. “This year, we’ve had a super abundance of moisture, and the species in many sites is not going to set any seed at all. Because of superior growing conditions, the plant grew too fast and was delicious food for a caterpillar species that has devoured every bite.”

Caterpillars are not the sole threat to the bear-poppy, one of 10 federally listed endangered or threatened species in Washington County. Development and recreation also lay claim to the poppy’s native habitats. And changes in both the political and physical climate challenge its immediate survival. While plants here have adapted to many adverse conditions–salty soil low in nutrients, a broad sky that lacks rain, and temperatures that reach extremes in both cold and heat–they have no means to adapt to the tires of motorcycles or the blades of bulldozers.

Located where the biological provinces of the hot Mojave Desert and the high, colder desert overlap, southwestern Utah has tremendous diversity in plant and animal populations. And whereas much of western Utah was anciently covered by a lake that left deposits of mixed geologic materials, southern Utah’s unique geologic deposits remain unmixed and modified only slightly by erosion. Thus, the mounds that support the Dwarf bear poppy contain thick layers of nearly pure gypsum.

“These surfaces are unlike anything else around. In order to grow, the plants have to be uniquely adapted. Over thousands of years, genes that permit growth on these unusual substrates have been selected. In many cases, it requires an entirely different species to survive on those surfaces,” says Harper.

“For this reason, this section of the West has more endemics–more things that are local–than other areas. Utah and Nevada have large numbers of rare and endangered species. That’s due to two things: geologic diversity and climatic diversity.”

Utah’s 15 species of endangered or threatened flowering plants include a number of species of cactus, the Ute ladies’-tresses orchid, Autumn buttercup, five members of the mustard family, the Maguire primrose, the Maguire daisy, and the Utah Dwarf bear-poppy.

One of the state’s rarest and perhaps strangest plants is Holmgren’s loco weed, a plant Harper has studied for many years. The species is currently under consideration for endangered status by the federal government. The plant wildflowers in early spring and then spends most of the year dormant, represented above ground only by an odd-looking tangle of ripening fruit pods that look like chili peppers. The plant is commonly known as a “loco weed” because it made horses that ate it “loco” or crazy. Interestingly, recent studies have shown that this incredibly rare plant has a whole pharmacy working inside it. It is rich in alkaloids, similar to those used in medicine. While loco weed species are numerous in Utah, this particular species is probably destined to remain rare, because wherever it’s found it now competes with three aggressive non-native plants.

“These alien species would not have been here 100 years ago,” says Van Buren, who has been working on native plant research for four years. “All are human-introduced annuals from the Mediterranean area–the African mustard, the red brome, and the storksbill.”

Then there’s the previously mentioned Utah Dwarf bear-poppy, named for its three-pronged, hand-like leaves, each covered with what appears to be a thin white layer of fur and topped with a tiny translucent “claw.” The wildflower itself has four broad, powder-white petals, petals that are pressed together in the cool of the morning but, in the afternoon hours, fan out to reveal a shaggy yellow pollen-covered face. In full bloom, one plant will produce as many as 200 wildflowers, each two inches across.

Botanists have determined that there are no bear-poppies like this anywhere else on the earth. And here in Utah, just nine plots remain near the cities of St. George, Bloomington, and Atkinville. When a species has fewer than 100,000 living plants, it’s considered fragile, a candidate for the endangered list; the bear-poppy has a population of less than 25,000.

Considering the elaborate dance of nature that must take place for a plant to survive, it’s a miracle that the poppy has made it to the edge of the 21st century. Its seeds are dispersed by hungry ants that snack on a fatty strip on the side of the seed. En route to their burrows, the ants drop seeds along their path, creating opportunity for the next generation of poppies. The seeds may lie dormant for several seasons, perhaps even 10 or 12 years, as desert plants assure their longevity by emerging only when the season promises to give adequate moisture and warmth for their needs.

“The seed is unusual because it has what botanists call an ‘immature embryo,’ ” says Harper. “In other words, when it is shed as

a ripe seed by the mother plant, the embryo is so small that it will not germinate immediately, but will grow only after an extended period of dormancy.

“If it had a seed like a radish or a corn plant, every seed put in the ground would germinate and grow the next season. You can imagine what would happen to the species if we had a long period of drought. All of the seedlings would die, and the species would become extinct,” he says.

Harper says the poppy, like many desert plants, must produce a large seed bank seven out of every 10 years or it won’t have the seed resources to survive. The seed has a discriminating seasonal palate, germinating only after a heavy rain, and only when temperatures are between 50 and 70 degrees. For cross-pollination, it also needs an unrelated plant within a few yards, the distance a bee or other pollinator will by seeking food.

Outside of caterpillars and climatic variations, humans and their recreational priorities–namely, motorcycles and other off-road vehicles -are the biggest threats to the plants.

“The gypsum surfaces, the only place where the poppies grow, are so hostile to most plants, and particularly woody plants, that they provide a surface that’s free of bushes and free of rock–which is like a magnet to off-road vehicle users. People can’t resist the temptation to try these gentle slopes with a powerful machine,” says Harper.

Although the Bloomington poppy preserve site is clearly marked as a no trespassing area, tire tracks crisscross the hilly wildflower beds. The Nature Conservancy helped construct a fence to surround the one-mile square preserve area, but enforcement is still a problem, says Lori Armstrong of the Bureau of Land Management.

“We still have lots of problems with trespassing, since our enforcement abilities are limited. We can’t spend 24 hours a day and every weekend out here. And all it takes is one vehicle, one tire track, to kill a plant,” says Armstrong, one of Harper’s former students who is now a rare-plant specialist.

Since the poppy’s habitat is in obvious conflict with other proposed land uses, some have suggested that the wildflowers could be relocated to a place where people don’t want to ride motorcycles. But what’s baffling is that the tiny black seeds of the poppy, and their fatty outgrowths full of nutrients, simply can’t tolerate the ideal growing situations of a BYU laboratory. Even when the seeds are seemingly provided with all of the discomforts of home, they are stubborn and unresponsive. Harper continues to study why the seeds insist on sprouting only with a clear view of I-15, in the path of bulldozers and off-road vehicles.

“Some of the best seed physiologists have tried to germinate those seeds. In all probability, the ability to culture it alone is non-existent. We can’t do it. Experience has demonstrated that only about 25 percent of our attempts to move plant species to new environments have been successful. So if we don’t preserve their native habitat, the species will probably go extinct,” says Harper.

When one considers the biological odds of survival for a plant with such narrow tolerances and then reads the headlines from Washington on the status of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), the question doesn’t seem to be, “Will the poppy become extinct?” but rather, “When?” and, “Which force will kill it first–nature or politics?” Most believe that Congress will at least cut the ESA’s influence, perhaps eliminating the act entirely and giving states full responsibility for environmental protection. Do these actions put the poppy and other fragile species at risk?

Harper is convinced that the federal Endangered Species Act, passed in 1973, did save the Dwarf bear-poppy (listed in 1979). Roughly $50,000 has been spent over the last 10 years in an attempt to preserve the species (money that has also benefitted other rare species that grow on similar terrain). But he’s hopeful that even if the ESA is significantly revised in the years ahead, some promising private efforts and enlightened Utah leaders and residents will still work to preserve uniqueness.

“I’m an optimist. I know a lot of people in our state government, and with or without a federal mandate, they’re going to protect rarity, they’re going to preserve uniqueness. They’re going to attempt to keep a natural environment that reminds us that Utah is really different from other states,” he says.

Given the complexity of managing one small species like the poppy on a few plots of land, one begins to understand the challenge of managing dozens or even hundreds of fragile plants and animals. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists some 960 fish, wildlife, and plant species as endangered or threatened, a list that would be longer if it had not been frozen by congressional edict in 1995.

Since half of all threatened or endangered species live on privately owned land and the ESA gives broad powers to federal agencies, the laws that protect endangered species have been a source of conflict in many communities. Many private citizens have opposed the mandate, saying it places the needs of tufts of greenery and spotted owls above their rights to determine how their family homesteads or timber stands will be managed.

“That the Fish and Wildlife Service treats private land as de facto wildlife refuges oftentimes makes [endangered] species unwanted residents,” writes an environmental research associate at the Competitive Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., whose opinion reflects a public sentiment. “Endangered and threatened species are an economic liability that devalues property.”

In such a political climate, Washington County’s unique plant and animal residents, celebrated and enjoyed by naturalists like Harper, can be viewed as both a blessing and a curse, says Bill Mader, an administrator in Washington County.

“In this county, we have over 40 candidate species that are listed by the federal government as threatened or endangered. In Utah, of all of the counties out there, we are the most heavily hit, if you want to look at it that way,” says Mader, who holds a PhD in zoology from BYU.

“But there are proactive ways to deal with that. It’s been a balance of wanting to do the right thing for species but also wanting to look out for property rights,” he says.

Mader is the administrator over a proposed Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) in the St. George area, a private effort to set aside 90 square miles in a preserve that will benefit many of the area’s fragile species, including the desert tortoise. HCP preserves often focus on entire ecosystems rather than individual species, and they can also permit more liberal use of land than previously allowed under endangered species protection laws. Many states, most notably California, have such plans. But even if the ESA appropriation is not renewed, these commitments made between private landowners and government agencies oVer hope for rare plants and animals in threatened habitats.

“I’m very optimistic. I know individual landowners who have deliberately set aside property with the idea that it would be included in the reserve for the benefit of biodiversity in general,” says Mader.

While it grows outside of the preserve area, the Dwarf bear-poppy will benefit from the habitat conservation plan, as protection of its habitat will be included in the plan’s charter. Harper sees the development of the preserve as a major cooperative effort, one that can hopefully be duplicated in many more communities.

“It would never have happened a few years ago, it would have been unthinkable,” he says. “They set aside 90 square miles of land that could have been developed–where a profit could have been made–but they willingly set it aside.”

Harper’s perspective is important because he has been a key figure in the region’s conservation efforts, receiving The Nature Conservancy’s highest national award in 1987 for his work.

A respected researcher and teacher, Harper will be missed when he retires from the BYU faculty this year (although he will still be involved in writing a book and advising on government contracts). In recent years, with booming development in many western cities, he has been called in to study populations and to provide scientifically sound advice on how best to manage these rare species.

Harper believes that science and information are critical tools as humans plan for the future and for responsible management of the planet’s diversity.

He opposes plans for wilderness or wildlife management that are not based upon solid science, and to that end he recently helped author a list of scientific criteria for management of wilderness lands.

“It is inescapable that as human populations increase, our impact on the natural world increases also. But it would be less severe if we planned ahead. That is the essence of good management of our natural resources,” he says.

Across Utah’s southern desert and into Nevada, Harper, his students,

and colleagues monitor as many as 1,000 individual plants at any given time, using both high-tech research methods and old-fashioned field work. By studying plants through their life cycles and counting the species in different areas, they have learned a great deal about desert survival tactics and the relationships between different plant and animal species.

“We tag every individual, then revisit the plots at least once a year to measure the diameter, the number of wildflowers, and whether the plant produces fruit. When you follow that year after year, you get a good idea about the life span and reproductive needs of a particular species,” says Van Buren, who spends several months each year studying Utah deserts inch by inch.

Van Buren has also been involved in collecting leaf tissue and taking

samples to Provo for genetic analysis, tests that are playing an increasingly important role in endangered species conservation. The DNA studies show how much unique genetic material exists in individual populations. While many factors affect a species, in theory, at least, the populations with the most genetic diversity have the best chance for survival. Deficiencies, like inability to resist disease or cold temperatures, will be exaggerated in populations that are genetically impoverished, making the population weak.

“Analysis of DNA gives us a better indication of the potential the population has for surviving in any kind of environmental situation,” says Van Buren.

“In some of the projects we’re involved with now, there are real problems that will eventually require trade-offs. Pressures on land use by development interests versus recreational use and the preservation of wild lands create complicated situations for managers. We can use the DNA to compare populations and perhaps identify those that harbor the most complete and unique genetic characteristics so that we can protect lands where those populations exist.”

Genetic testing has already affected the way the bear-poppy population is managed. One plot of nine was found to have unique genetic markers associated with it. The researchers had given up on the Atkinville plot, but the results mandated that they make additional efforts to preserve that genetic resource by moving seeds from surviving plants to safer habitats.

Technology has also helped Harper and his team differentiate a population of the California bear-poppy, a yellow-flowered species that grows in the Grand Canyon, from similar looking plants in the Las Vegas basin. “We will name it as a new variety of bear-poppy simply to call attention to the fact that it’s really genetically different than the others and therefore should be protected as a source of genetic enrichment for other populations of the species,” Harper says.

Perhaps the most disheartening part of Harper’s work is when the research isn’t convincing enough to save endangered populations. Against Harper’s recommendations, a western city put a golf course over the habitat of a rare poppy. Another constructed an airport runway over the critical habitat of several sensitive species. These decisions, made with full knowledge of their ramifications, have increased the stress on several rare species, enhancing the likelihood of their eventual extinction.

DNA analysis, because it has given a means to quantify diversity, has also opened some philosophical questions about the absolute value of uniqueness. The bear-poppy’s plight reduces the issue to fundamentals because the plant has no known economic value to humans. While it does produce some interesting alkaloids, it’s not necessarily on par with plants that have immediate uses for humans, plants that provide food or useful chemicals, or plants that pull heavy metals or radioactive elements from polluted soil. “The poppy forces us to consider the worth of beauty alone,” says Harper.

“Everything doesn’t have to have an economic value. But everything does have value. Sometimes we’re not quite sure if it’s for the beauty alone or whether a plant may have value that is not yet discovered, but they all have their value,” he says.

“If we build museums to save our works of art, aren’t we justified in attempting to preserve the natural beauty of the earth around us? Our sense of beauty had its origin–its roots–in nature. Our sense of symmetry came from the natural world, and our sense of color combinations and aesthetic appeal came initially from nature.”

Harper says the natural world not only gave us our sense of beauty, it literally makes human survival possible. While he is an advocate of science and scientific inquiry, he admits its weaknesses. He believes that society, focused on technology, has neglected this link between human survival and survival of other species.

“We have an immense arrogance that our technology can cure all ills in our society,” he says. “But we live on a planet that is very complex, and we’re totally dependent upon it. Either we live with that natural environment or we absolutely lose all things of value, because we can’t exist without the natural world.

“The very existence of nations is dependent upon the capacity to produce food and fiber, as well as clean water to run its industries and scrub its people. All of that contributes to wealth of nations. Nations could not exist without that natural base.

“An educated population should understand the linkage between high culture and the natural world. They really are inseparable.”

Van Buren sees genetic resources as not unlike other natural resources on the earth, all of which can potentially benefit humans directly or indirectly.

“I look at the genes of a particular species as just part of the natural resources that we have. Whether it be a running stream or anything else, it’s a resource, one that represents unique material. And when you see a species disappear from that resource pool, you lose its value forever,” she says.

So how will the world change if the Utah Dwarf bear-poppy’s lease expires and the species becomes extinct, either through indifference or deliberate acts of herbicide? Will motorcycle enthusiasts rejoice as they gain a gently sloping paradise of unencumbered soil? Will developers excavate former poppy habitats, finding space for condominiums or convenience stores? Will Mormon hymnals be reprinted to read “Earth With Her 9,999 Flowers,” throwing the delicate balance of music and spirit out of cadence?

“If we look at the fossil record, 99.9 percent of the species that ever lived on earth are extinct; we know them only as fossils,” says Harper. “So survival of any species is a temporary thing.”

“I think with all rare plants, extinction is the inevitable consequence. I have friends who say, ‘Well, why not just let the poppy go extinct? Get the darn thing out of the way and quit spending money on it and worrying about it.’ But I don’t know how people can just destroy it. To me, that seems immoral.

“It’s probably silly to say, but I love these things. I can’t imagine living on this planet without my native companions. I don’t love them like I love my wife or children, but they have become dear friends. And I draw a great deal of comfort from knowing that they’re well, like people draw comfort from knowing that their children are well,” says Harper.

It may be that very little will change if a tiny plant whose leaves look like green bear paws becomes a parcel of memory in the minds of a few botanists and sentimentalists. The question may not ultimately have global ramifications, Harper says, but it may be important for us at the personal level: How will we change, in our hearts and minds, knowing that we had the chance to save something beautiful and we let that chance slip away?