Amid cheers and protests, Vice President Dick Cheney receives a BYU honorary doctorate.

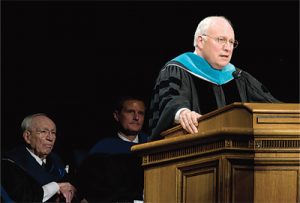

Church President Gordon B. Hinckley and Elder David A. Bednar listen as Vice President Cheney addresses a captive commencement audience.

As commencement addresses go, it was shorter and better received than most. But the buildup to Vice President Dick Cheney’s speech to BYU graduates in April involved weeks of debate and discussion.

The announcement that he would speak at BYU was followed by waves of reaction, and the news media clamored to headline the story. Yet in the end, Cheney’s BYU speech didn’t mention politics in the slightest. Instead, he spoke to graduates about opportunities and second chances. “Most of us end up needing one,” he said.

The Marriott Center filled to capacity for the April 26 event, where Cheney was awarded an honorary doctorate for his lifelong career in public service. The 6,000 graduates and their families cheered when he acknowledged the attendance of the chairman of the university’s board of trustees—and a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom—Church President Gordon B. Hinckley.

Cheney also elicited applause by recognizing BYU’s rank as the no. 1 stone-cold sober school by the Princeton Review and warmed the audience with the mention of the pioneer heritage of his wife, Lynne. Two of her great-grandparents graduated from Brigham Young Academy.

The crowd lauded his speech—perhaps expected in a county presupposed to be a citadel of support for the present U.S. administration.

Yet the vice president’s visit also brought out those in opposition to his current policies. As debate ensued, the university maintained its strict political neutrality.

“The university is a place for the discussion of a variety of viewpoints,” says BYU spokeswoman Carri Phippen Jenkins (BA ’83). “An invitation to a speaker does not imply endorsement or agreement. Nor does having a political neutrality policy mean we cannot engage in political debate and discussion.”

The David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies sponsored a panel discussion entitled “Vice President Cheney and the Global War on Terror.” Students listened to and questioned four faculty members, including BYU associate professor of political science Darren G. Hawkins, who openly critiqued many of Cheney’s policies—but not the university’s invitation.

“I have always seen [Cheney’s] policies and values as the main issue here,” Hawkins says. “BYU is engaging in public dialogue, and that’s a good thing. Will that sometimes involve people we may disagree with? Yes, absolutely. But universities are laboratories for ideas.”

Jenkins emphasizes the role of the university as a place for respectful and informative dialogue, hosting thought-provoking speakers of varied viewpoints. This fall the schedule of forum assembly speakers includes U.S. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and U.S. Senate majority leader Harry Reid, D-Nev. “BYU does not invite speakers based on their partisan political affiliation, nor does it award honorary doctorates for these reasons,” Jenkins says. “We encourage our campus community to be involved in the political process, to be active citizens, and to participate in discussions about important issues impacting our world.”

BYU also allows an opportunity for public expression to members of the campus community. This spring the College Republicans and the College Democrats made three requests for public expression through approved university processes. All were granted. And none prevented graduates, in cap and gown, from taking pride in their academic achievement.

After receiving the honorary doctorate of public service, Cheney reminded his audience, “This day belongs to the fine young men and women who have actually earned their degrees.”