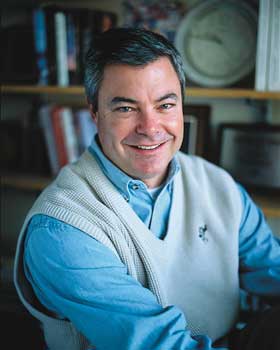

Dorothy and friends had a pity party in Oz until they learned a simple truth. In a BYU Alumni webcast, a bestselling coauthor of The Oz Principle stressed the importance of accountability.

When it comes to accomplishing anything, if you don’t practice accountability you can’t achieve the extraordinary—according to three-time New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestselling authors Roger C. Connors (MBA ’85), Thomas A. Smith (MBA ’84), and Craig R. Hickman (BA ’74).

At a recent webcast sponsored by the BYU Alumni Association, Connors shared several insights from their book, The Oz Principle: Getting Results Through Individual and Organizational Accountability. He discussed the vital role of accountability in achieving business and personal results. He also shared a warning message: “Accountability is in a crisis in organizations and society, affecting both morale and results.”

“There is a critical need for accountability in organizations,” Connors said. “Accountability, as a personal and organizational attribute, is a core idea that defines how we relate to one another, how we make agreements with oneanother, and how we keep those agreements. It determines how well we will execute on every individual, team, and organizational initiative.”

In The Oz Principle Connors, Smith, and Hickman use the Wizard of Oz to illustrate the journey to greater accountability. In the popular L. Frank Baum children’s book, Dorothy meets the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and the Cowardly Lion. They have a pity party and bemoan their fates: Dorothy wants to go home, the Scarecrow wants a brain, the Tin Man wants a heart, and the Lion wants courage.

Through no fault of their own, they find themselves in circumstances they do not believe they can control. But as they follow a yellow road to find a wizard they think can solve their problems, they have adventures in which the Scarecrow shows great wisdom, the Tin Man displays enormous h eart, and the Lion demonstrates tremendous courage. Dorothy, as it turns out, only has to click her heels to return home. The quartet ultimately learns that while the wizard is a smoke-blowing fraud, they themselves have the ability to take accountability for their lives—thus overcoming the obstacles they face and resisting victimization.

eart, and the Lion demonstrates tremendous courage. Dorothy, as it turns out, only has to click her heels to return home. The quartet ultimately learns that while the wizard is a smoke-blowing fraud, they themselves have the ability to take accountability for their lives—thus overcoming the obstacles they face and resisting victimization.

Among the major roadblocks in the journey to greater accountability is a lack of clarity concerning goals. Connors said he and Smith once interviewed senior executives at a pharmaceutical company and asked them what the key result was that their company needed to achieve. None were willing to answer. They finally passed around sheets of paper and had the executives write down their organization’s financial objective for that year. As they read the answers, they discovered a $300 million variance between the high and low number that was turned in from the team.

“These were outstanding business leaders, but they lacked clarity around the result they needed to achieve,” Connors explained. “When people are held accountable for an unclear result, they feel ambushed and taken advantage of, rather than empowered.” The Oz Principle’s mantra is simple: “Accountability begins by clearly defining results.”

Connors also shared the experience of a technology business and a truck driver. The business had a critical date when a product needed to be delivered or they would lose the sale. They hired a contract truck driver who began his delivery journey with the sight of hundreds of company employees in his rearview mirror waving and wishing him a speedy journey.

He drove several hours before arriving at his first weigh station. His load was 50 pounds too heavy, and it would take an additional day to reprocess the paperwork. With the thought of hundreds of cheering people depending on him, he turned around and pulled into the first rest stop he could find. He walked around the truck and asked, “What can I do to lighten my load?” Then he found some items he didn’t need and stashed them in a ditch. He returned to the station, passed inspection, and made the shipment on time.

“The company still talks about the driver,” Connors said. “They use it as an example of what it means to be accountable.”

The crucial element of personal and organizational accountability should be woven into the very fabric of the business character, process, and culture of organizational life, according to Connors, Smith, and Hickman. They advocate using a model that details what they call “Above the Line” steps to accountability as opposed to the blame game or “Below the Line” thinking.

With Below the Line thinking, one finds victims and victims of victims. Attitudes include “wait and see,” “tell me what to do,” and “it’s not my job” and are accompanied by ignoring and denying problems, finger pointing, covering your tail, and general confusion.

Above the Line thinking can become a transforming power. The individual or corporation willing to be accountable will see a problem, acknowledge it, solve it, and then carry it out. It is common sense but not necessarily common practice.

“People who take accountability make things happen,” Connors asserted, “and with a company full of accountable people, extraordinary things can be achieved.”

Web: Watch a recording of Roger Connors’ webcast at more.byu.edu/connors.