Works of Grace

Works of Grace

The BYU Museum of Art director and religious works curator provide insights into paintings of the Savior— some familiar to viewers— by three European masters.

By Jessica Jarman Reschke (’14) in the Winter 2014 Issue

Bathed in soft cool light, a sorrowful Savior kneels in prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane, enveloped in a tender angelic embrace. “And there appeared an angel unto him from heaven, strengthening him” (Luke 22:43). The towering altarpiece by Danish artist Frans Schwartz, titled Agony in the Garden, depicts the sacrifice that occurred in the Garden of Gethsemane, when Christ took upon Himself the sufferings of the world.

“This painting portrays that suffering in an incredibly deep and meaningful way,” says Mark A. Magleby (BA ’89), director of the BYU Museum of Art (MOA). “There is a forlorn pain in His eyes. They are unblinking. He has entered into this with eyes wide open about the importance of what He is doing.”

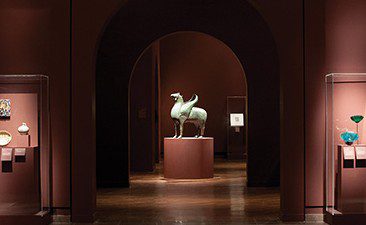

Jesus Christ’s gift to mankind is a theme that runs deeply through Sacred Gifts: The Religious Art of Carl Bloch, Heinrich Hofmann, and Frans Schwartz, one of the MOA’s most ambitious exhibitions. From the talents of the artists to the loaned paintings from churches and museums to the generosity of donors to the ultimate gift of the Savior, “there are multiple levels of gifts represented in this exhibition,” notes Dawn Chambers Pheysey (BS ’66, MA ’93), curator of religious art at BYU.

After the overwhelmingly positive response to a 2010–11 show featuring altarpieces and other paintings by Carl Bloch, MOA curators began working on an exhibit that would bring together works from three of 19th-century Europe’s most talented and prolific religious artists. To do so they had to persuade churches and museums in Denmark, Sweden, Germany, and New York to lend their paintings, most of which had never left their chapels since they were installed in the late 1800s.

Many of these paintings are familiar to a Latter-day Saint audience. The works of Bloch and Hofmann regularly appear on the covers of Church publications and on the walls of meetinghouses. “We wanted to have some that were familiar, but also wanted to introduce some that weren’t,” says Pheysey. The exhibit begins with the dramatic presentation of Schwartz’s Agony in the Garden and ends with Bloch’s bold Resurrection of Christ. “You go through those doors and you walk in and you feel the presence of Jesus,” Karen McVoy-Stone, council-member at The Riverside Church in New York City, says of the exhibit. “You look at every picture from all three artists, and you feel the spirit of Jesus. You feel these men were imbued with the Spirit to produce incredible art.”

Here curator Pheysey and MOA director Magleby share personal insights on some of the exhibit’s offerings.

Johann Michael Ferdinand Heinrich Hofmand (1824-1911)

Born in Germany to artistic parents who encouraged his creative gifts, Heinrich Hofmann went on to become one of the most celebrated German painters of the late 19th century. Tutored by his mother, who taught drawing classes, Hofmann became an apprentice to a copper engraver at 16, and two years later he entered the acclaimed Düsseldorf Art Academy. At the time, Christian subjects were the focus of the school’s curriculum. During his three years at the academy, Hofmann earned a place in the top master class.

For 12 years after his schooling, Hofmann studied and painted in all of Europe’s major centers of art. Based on his study of German, Dutch, and Italian masters, Hofmann developed a distinctive style that was richly realistic. It wasn’t until after he married that Hofmann began painting the portraits that supported his family and built his reputation. In 1862 he moved to Dresden, where he worked for five decades.

Hofmann’s later career is marked by an increasing focus on religious subjects that reflected his own deep personal faith, which included a strong devotion to the scriptures. Hofmann’s is a “beautifully compassionate yet psychologically intense Christ,” says Magleby, who notes that some of the most memorable images of the Savior have come from Hofmann’s brush. He painted the Savior so often that he did not use a model.

Several of his works were collected by Americans, which ultimately saved them from bombing during World War II. “After the war was over, no one wanted religious paintings,” says Pheysey. “This is the first time that some of these have been displayed publicly since before World War II.”

Portrait of Christ, the Savior

Hofmann painted this portrait for himself, says Pheysey. “He wanted to hang it above his bed so every night he could look at it and think, ‘Have I kept the commandments this day?’” This painting has similarly inspired President Thomas S. Monson, who has had a copy in his office since he was a young bishop in the 1950s. Of Hofmann’s portrayal of Christ, President Monson has said, “Look at the kindness in those eyes. Look at the warmth of expression. When facing difficult situations, I often look at it and ask myself, ‘What would He do?’ Then I have tried to respond accordingly.”

Christ and the Rich Young Ruler

The detail of Christ’s head from this painting has been reproduced perhaps more than any other image of the Savior. “It’s often cropped, just to show His face—the beautiful, compassionate, serious, mature, noble face,” says Magleby. Hofmann is often praised for his ability to capture empathy and emotion, and in this painting he portrays the poignant mixture of compassion and sorrow that the Savior feels when men and women refuse to sacrifice personal desires to follow Him.

In this painting, the Savior asks a rich young man to sell all he has and to give it to the poor. This was a deeply personal topic for Hofmann, “a great benefactor to the poor,” says Pheysey. “He was especially concerned about them at Christmastime. He would often invite them to come to his home, and he would give presents to the children.”

Hofmann displayed this painting in his studio for 16 years, refusing to part with it because it was a favorite of his wife, Elizabeth. The aging artist reluctantly sold it to an American collector in 1904, “after he was offered more for it than he’d ever been offered for any other painting,” says Pheysey. John D. Rockefeller Jr. later purchased the painting and donated it to The Riverside Church in 1932.

Carl Heinrich Bloch (1834–90)

A native of Copenhagen, Carl Bloch was born one of 10 children to a middle-class family. Bloch had no early aspirations to be an artist. At 11 he enrolled in a preparatory school for naval officers “because it sounded like fun,” says Pheysey. While at the naval academy, Bloch discovered that he had a love for art. “He would pretend to read his schoolbooks, but he would have paper and be drawing images inside the book instead,” said Pheysey in a BYU Education Week presentation.

At 15 he enrolled in the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and spent the next decade feverishly drawing and painting, to the acclaim of his teachers and peers. “The academies were very rigorous,” says Pheysey. “They would draw from early in the morning until late in the evening, day after day, just drawing.” Bloch received many awards for his paintings, including a scholarship that allowed him to travel and study in Italy. Bloch was particularly fond of Rembrandt, but he also studied the great Italian masters. During his time in Rome, Bloch gained recognition for his amusing paintings of street vendors and monks, but it was four large history paintings that established his reputation as an artist. These paintings, met with national acclaim in Denmark, led to Bloch’s commission for the 23 paintings in the King’s Oratory at Frederiksborg Castle and for eight large altar paintings for Danish churches.

In his day Bloch was one of the best-known Danish painters. His work was noted for its dramatic composition, theatrical use of light and dark tones, and bold, realistic figures. Though his prolific body of work included more than 250 paintings and 78 etchings spanning a variety of subjects, Bloch valued his religious works as some of his most meaningful contributions.

The Resurrection

This massive altarpiece, the largest of Bloch’s paintings, was the most difficult to add to the exhibit. The MOA had approached the church where it was housed 10 times over the last seven years. “We of course asked for this for the Bloch exhibit [in 2010],” says Magleby. “But they couldn’t imagine ever taking it down.” A change in the church council membership is what ultimately helped in convincing the church to loan the altarpiece. “The current head priest has been very supportive,” says Pheysey.

“You can see the six and the one at the same time on the die [in the foreground], even though they’re opposites,” says Magleby, who says Bloch’s use of this impossible combination of numbers suggests symbolic significance. Rasmus Nøjgaard, parish priest at Sankt Jakobs Kirke, notes that six, a winning number in dice games, might signify that we are all winners because of the Resurrection of Christ. The number three implies the Trinity, and the number one, the Savior and the witness that there is “only one way.” Jewish symbolism designates the number seven (six and one) as the divine number of completion, which could signify the fulfillment of the mission of Christ.

The blooming lilies bursting from the tomb represent purity and rebirth, says Magleby. The abandoned fire, spear, and helmet are reminders of the guards who fled when the stone began to roll away.

Christ at Emmaus

The resurrected Savior sits at a table with two of His disciples, who do not yet recognize Him. Christ offers them bread, just as He did at the Last Supper only days earlier. Bloch captures the moment of realization for the disciples. “They’ve been with Christ for a while and not recognized Him,” says Magleby. “There’s already food that’s been served, and at this moment Christ is eucharistically handing the bread, . . . and they are seeing the transformation. It is the moment where He is fully there and immediately gone that Bloch captures. We cannot see their faces, but we know their mouths have dropped open as they recognize this.”

“The composition of the window . . . gives depth,” says Magleby. “It shows that it is eventide and gives you a sense of the time of day.” The walking stick, basket, and gourd in the foreground suggest the disciples’ journey.

“After we had this cleaned, it almost looked like a new painting,” says Pheysey. At the church in Sweden, there is an altar in front of the painting, which would sometimes be splattered with candle wax. “But now there’s no trace of that. Now you can see details that you never could before, like the facial expression of the woman in the back.”

The Mocking of Christ with Mary and the Annunciate and Mary the Elder

This polyptych, a painting with multiple panels, is on loan from a Danish church named after Mary, who is depicted on both sides. The first of the five panels shows Mary at the time of the Annunciation. Clothed in blue to represent calm and purity, the Virgin Mary embraces her robes in anticipation of the mission the Lord has given her.

The second panel depicts an unruly mob demanding the release of the murderer Barabbas and the death of Jesus. In the bottom corner is a young boy with two men who might be his father and grandfather. “It makes you think of the generations of families and how the decision of a parent or grandparent affects a child,” says Pheysey. “The child mimics what he sees. On his own he probably never would have been part of this crowd.”

Clothed in a red robe and crowned with thorns, the bound and battered Christ stands undaunted. “The expression is a bit different than we’re used to, but it’s so engaging, says Pheysey. “His eyes bore right into you. He looks firm, resolute, and calm.” Under the careful lighting of the MOA display, His crown of thorns appears to emerge from the painting.

Vindictive priests, Roman officials, and soldiers silently approve the injustice. “They look so smug,” says Pheysey. “They’re the ones who’ve incited the crowd to fight for the crucifixion of Jesus.”

“All of the architecture on the right is Roman, and on the left are the Jewish temple and walls of the city,” says Magleby. “They give a context for these various forces, all of which are combined to bring down Jesus—and Jesus is confidently refusing.”

In the final panel, an older Mary witnesses her son’s condemnation and crucifixion 33 years after His birth. This Mary wears a look of serene, somber understanding of the sacrifice of Christ.

Restoring Beauty

For churches and museums that were reluctant to loan their paintings, one incentive was the MOA’s offer to pay for conservation. “All of the paintings needed to be cleaned,” says Pheysey. Four different conservation labs worked on paintings in this exhibit—some through the MOA’s conservator in Denver, some in New York, and others at the National Museum of Denmark, in Copenhagen. This kind of conservation begins with removing the varnish so the painting can be meticulously cleaned. Then the canvases are revarnished and sometimes restretched. “They try to use materials that would have been from that particular time period,” says Pheysey. “They can take small samples of the paint, analyze it, and determine the exact content of the paint.” Sometimes, the cleaning reveals details that have long been hidden by candle smoke or dirt that has built up over time.

Johan Georg Frans Schwartz (1850-1917)

Frans Schwartz is the least known of the three artists featured in this exhibition. “He was independently wealthy, so even though he was extremely talented, he didn’t have to sell his work,” says Pheysey. “He did a lot of work for free and rarely exhibited. We’re excited to introduce him to our audiences.”

Born into a Copenhagen family with a thriving wood- and ivory-turning business, Schwartz displayed creative talent early on. By 16 the budding artist had earned his way into the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, where he may have been a student of Carl Bloch. “We don’t know exactly how close the relationship was,” says Magleby. “We know that he did a portrait of Bloch for which Bloch would have sat.”

After six years of intensive study, Schwartz graduated from the Royal Academy, traveled to Spain to paint, and exhibited several paintings. After his father’s death, he inherited the family business and stepped away from painting for a time. Even though he was not painting for a living, the reclusive and eccentric artist continued to make ceramic decorations and used his earnings to found a private art school.

Despite his relatively small body of work, Schwartz is praised for the emotional power of his paintings—especially in the figures’ faces. Schwartz’s style is more modern and captures the feeling of his scenes with a more painterly, loose stroke than the academic styles of Bloch and Hofmann.

Generous and deeply religious, Schwartz donated some of his greatest works to churches. He also bequeathed his entire fortune to the artistic enhancement of Copenhagen’s public buildings.

Agony in the Garden

“This painting to me is the most powerful of the exhibition,” says Pheysey. “We wanted to start the exhibition with a little-known artist and something our patrons hadn’t seen before. It’s such a tender, powerful image of the angel’s wings holding back the darkness, even just for a moment.”

Magleby appreciates Schwartz’s cool colors here, very different from the deep reds of Bloch. According to Magleby, they “represent the loneliness of fulfilling the demands of the Atonement and [are true to] the inconsolable expression on His face.”

Rather than replace the loaned altarpiece with a print, “the Nørresundby congregation has left its place in their church vacant to remind them that their absent angel has a duty elsewhere, but will return to them soon,” says Pheysey.