Voice of the Cougars

After nearly two decades and more than 800 sporting events, BYU’s play-by-play radio announcer is still perfecting his game.

By Peter B. Gardner in the Winter 2015 Issue

Photography by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

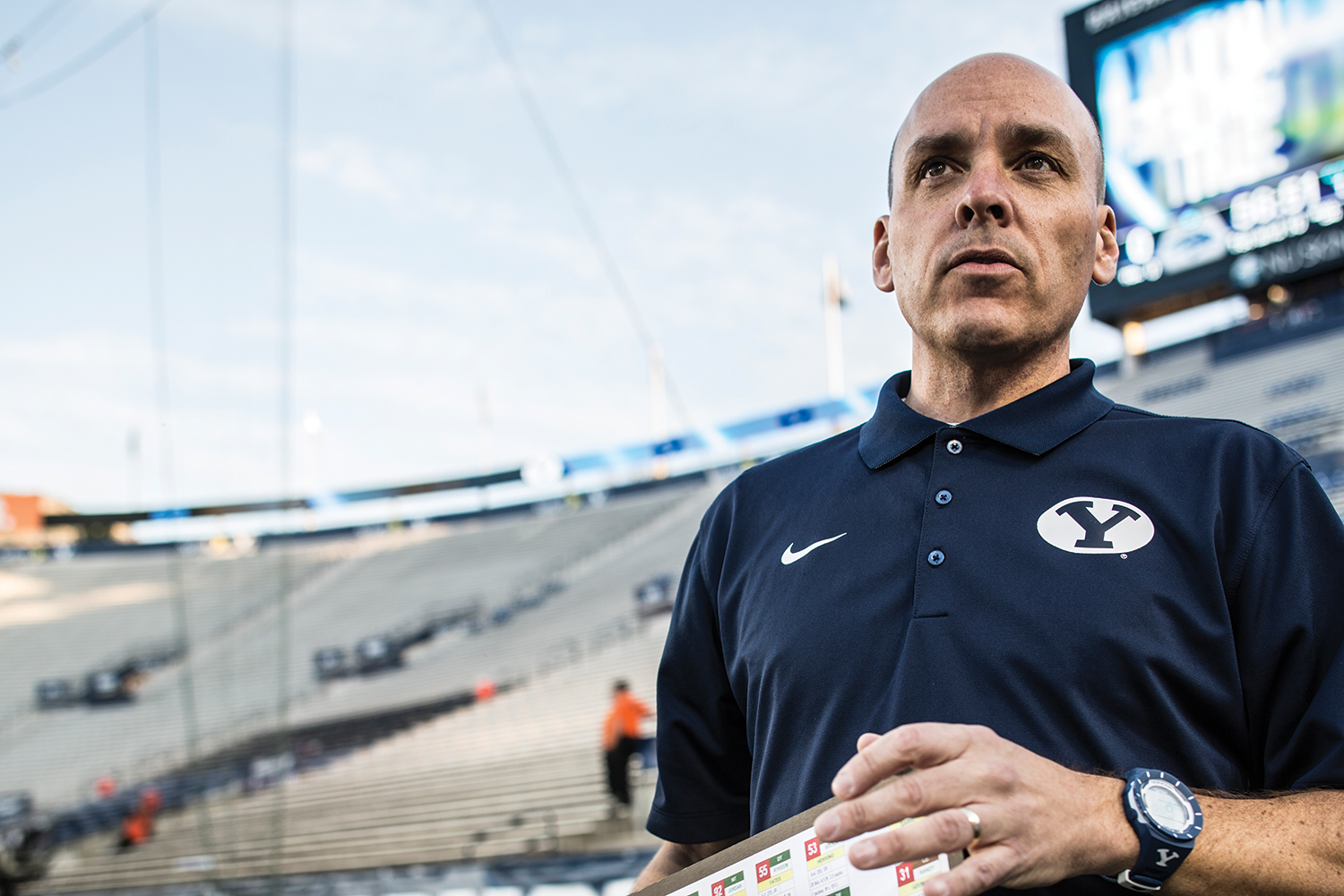

It’s a pen. But one might wonder, given all the functions it performs for Gregory A. Wrubell (BA ’90) during a six-hour football radio broadcast. In one moment, it’s a conductor’s baton directing the efforts of the broadcast team. In another, it’s a paintbrush, swished in broad gestures as Wrubell verbally sketches the gridiron action nearly 10 stories below. Mostly, it is an outlet for nervous energy. “He works that pen,” says broadcast booth-mate Marc F. Lyons (BS ’70). Wrubell will click and unclick it dozens of times a minute and occasionally fling it against the desk when something goes awry on the field or in the booth.

It’s a setting Wrubell calls “orchestrated chaos.” Set aside the technical complexities of a radio broadcast—and there are plenty. More challenging is harnessing an unrelenting barrage of information into a play-by-play narrative that is coherent—let alone witty, insightful, poetic.

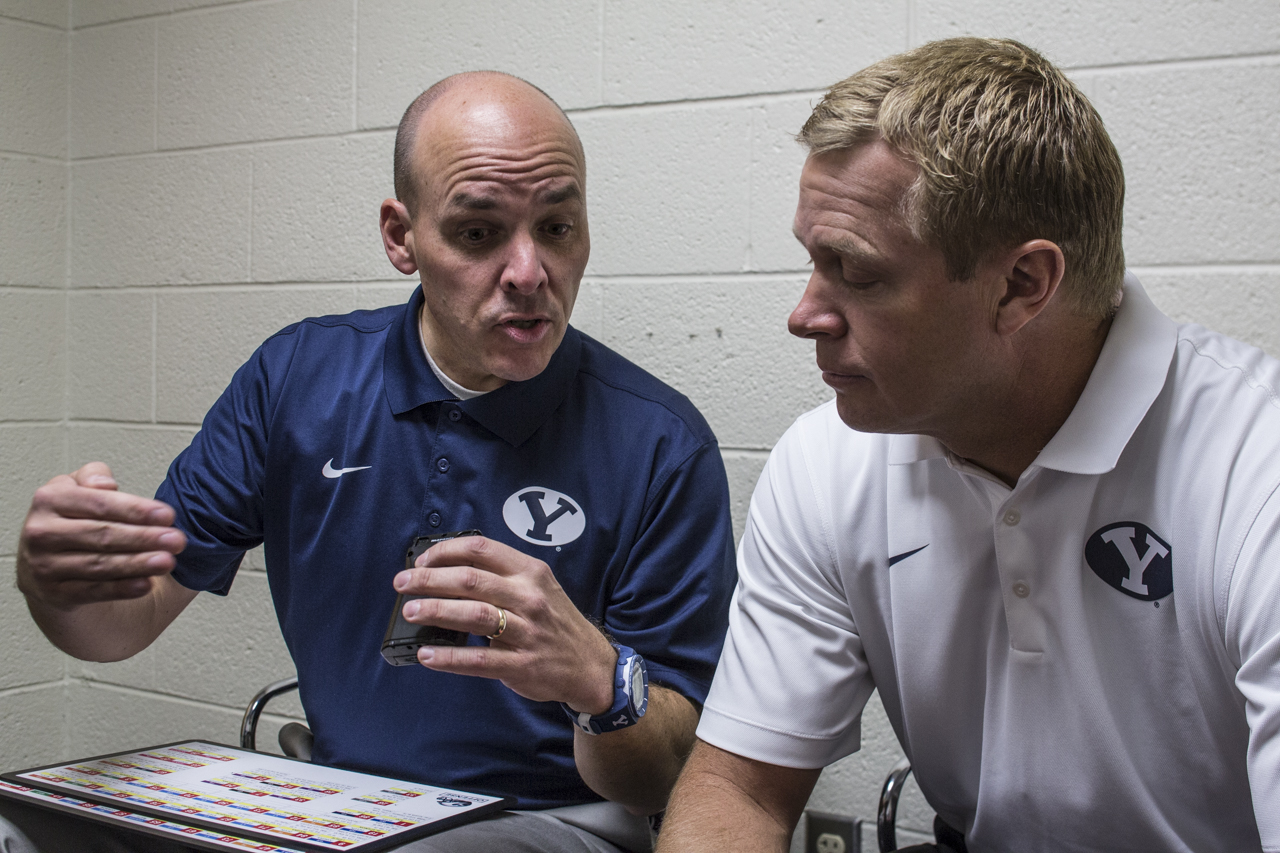

The inputs fly in from all around. Through wall-sized windows Wrubell’s eyes are trained on the game action, unfolding at rapid-fire pace (no thanks to offensive coordinator Robert O. Anae [BA ’86, PhD ’99] and his “go-fast, go-hard” tempo). Wrubell is flanked on the left by spotter Doug W. Martin (’73), who helps identify players on the field, and on the right by stats man Ralph V. Sokolowsky (BA ’72, MPA ’79), who scribbles Post-it messages (Drive: 73 yards, 13 plays, 5:04) and slaps them on the glass for Wrubell to weave into his commentary. On the desk before him an iPad flashes out statistical updates; a procession of tweets marches endlessly down an iPhone screen; and cheat sheets with notes about the teams, colorful “spotting boards,” and printouts full of obscure stats (half a ream’s worth) all sit at the ready.

Wrubell’s ability to funnel it all, in real time, into a compelling narrative astounds Lyons. “[The] play happens so quickly—pow, just that fast—and Greg is able to verbalize everything that he sees. . . . His vocabulary is perfect for what needs to be said.”

Calling BYU sporting events—football, men’s basketball, and, starting in 2014, women’s soccer games—for nearly two decades, Wrubell is known far and wide as the Voice of the Cougars. But he might just as well be known as the eyes and ears of the Cougar fan. Legions of listeners hunched at radios and computers around the world have come to count on him to transport them into the fray of a Cougar game day.

VOICE LESSONS

Greg Wrubell doesn’t play sports. Of course, growing up in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, in Canada’s central plains, Greg played hockey like every other kid. But he gave that up at age 14. “Wasn’t any good,” he shrugs.

Greg’s real talent—and, in grade school, his curse—was for words. The precocious kid who skipped first grade just couldn’t stop yapping. “I was a motormouth,” he admits. “I talked fast. I talked a lot. I’d get told to be quiet quite a bit.”

As he got older, he channeled voice and verbosity into “nerdy-type stuff”—public-speaking contests, drama, and choir while developing an interest in broadcast journalism. In high school, after the family moved to Calgary, Alberta, he competed with a quiz bowl team on local TV.

“I loved books and lists and numbers,” says Wrubell. “I watched a ton of sports and researched a lot about it.” He geeked out over hockey, curling, Canadian football, baseball. He’d collect cards and “all other things that dealt with statistics and minutia.”

But when Wrubell, who joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with his family at age 9, headed south to BYU in the fall of 1984, he knew nothing of Cougar sports.

That all changed his very first day on campus, as Wrubell found himself sitting with thousands of other students in the Marriott Center to watch the broadcast of a football contest between BYU and Pitt, the first game in BYU’s march to an eventual national championship. From that moment, this sports junkie was hooked. He attended all the home football and men’s basketball games and would get a daily sports fix watching basketball practices at the Marriott Center after his classes.

His first week of school, the 17-year-old strode into the KBYU studios and located the news director: “Hi, I’m a freshman. I’d love to be a broadcaster. Put me to work.” The director took Wrubell up on his offer and sent him off to cover a story about the fencing club—a story that landed on Channel 11.

Though he doesn’t remember it, friends from college tell Wrubell that he said he’d like to someday succeed Paul James, BYU’s long-standing play-by-play football and basketball announcer. Whatever he actually said about such dreams, he now says he never really expected it to happen. “Paul James was a legend,” he says, noting that there wasn’t any clear path to landing a gig like that.

“The parts I can control, I want to control. Once kickoff happens it’s seat of your pants for the next six hours.” —Greg Wrubell

Following a mission to Brazil, Wrubell began dating Tauna Frehner (BA ’89), his TA from a broadcast journalism class. She says Greg was sharp, funny, and “just smart,” and they enjoyed discussing world events and sports. Naturally, their first date was to a BYU basketball game.

While still a student, Wrubell got his big break when he landed a summer internship with KSL’s Chris Tunis, a pioneer in sports talk radio. “He had a sports talk show back in the day before sports talk was a genre,” says Wrubell. “He was a fanatic about detail. . . . He knew everything about the subject he was going to address.”

After Greg and Tauna married at the end of the summer, Wrubell parlayed his internship at KSL into weekend work and then night shifts on the news desk while, bleary-eyed, he finished up his schooling.

In 1992 James invited Wrubell, whom he calls “extremely sharp and quick-witted,” to join his football broadcast team, walking the sidelines as the on-field reporter. The role gave Wrubell an up-close perspective on the inner workings of a broadcast and mentoring from his idol.

Perspective notwithstanding, nothing could have prepared Wrubell for the 1996 BYU-Utah rivalry game. When the KSL engineer sent word during the pregame show that James was experiencing heart-attack symptoms and told Wrubell to get ready to call the game, Wrubell nearly joined his boss in cardiac arrest.

“I panicked,” says Wrubell, who’d meticulously prepared to offer sideline commentary, not call a game.

To the frustration of paramedics and the relief of Wrubell, James refused to leave the booth and proceeded to call the game.

That night he phoned Wrubell from the hospital: “I’m having six bypasses in the morning. You’ve got to get on a plane to Seattle to do a basketball game.”

Thus Greg Wrubell, who had never before called a sporting event, became a play-by-play announcer of BYU sports.

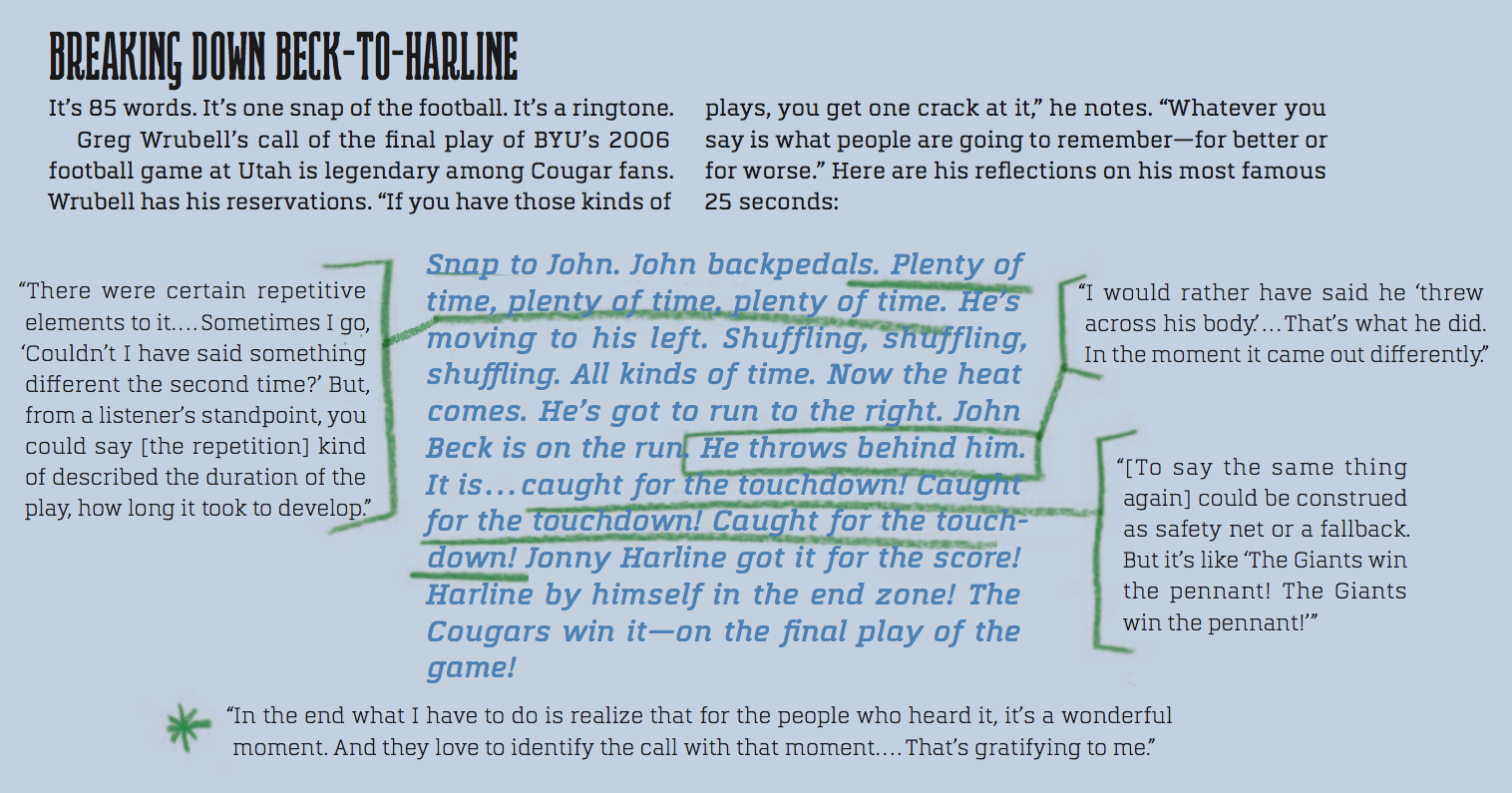

THE QUEST FOR PERFECTION

“Greg could probably work part-time as a NASCAR racer,” says Lyons, who cites a trip to Fort Worth, Texas, where he, Wrubell, and sideline reporter Nathan L. Meikle (BS ’06) were mired in heavy traffic en route to broadcast the BYU football game against Texas Christian. Wrubell, at the wheel of the rental car, wasn’t about to let road congestion mess up their broadcast. “He took off,” Lyons recalls, “and he was scaring us, weaving in and out of traffic, [saying], ‘Hang on! Hang on!’”

They arrived at the stadium just in time, but when they looked into the back seat, they saw Meikle, “just as sick as can be from rolling around.” Meikle stumbled from the car and promptly threw up.

But the broadcast began on time.

In some 800 games since he first stood in for Paul James, Wrubell has become fanatical about getting it right—from on-time starts to burnishing his descriptions with metaphor and alliteration to pronouncing names in a way that would make even the Manumaleuna and Leuta-Douyere families proud.

“There’s nobody like Greg Wrubell,” says basketball broadcast partner Mark B. Durrant (BA ’95, JD ’99), “and I say that with all of the love in the world. He’s enormously dedicated to his craft. . . . He cares a lot about the product we put over the airwaves.”

“[The] play happens so quickly—pow, just that fast—and Greg is able to verbalize everything. . . . His vocabulary is perfect for what needs to be said.” —Mark Lyons

Wrubell, who fully took over basketball responsibilities from James in the 1997–98 season and football in 2001, says a successful call is both an art and a science—and the science comes first.

“The science is dealing with everything that gives you the ability to speak on game day,” he says. If you are prepared, “when you sit down you can just do your job. Because the job itself is hard enough.”

Wrubell approximates that he spends four hours of prep time for every hour on the air. He watches game film, attends practices, updates his databases of proprietary stats, and creates detailed spotting boards for both teams complete with offensive and defensive formations, starters and backups for each position, and a few facts about each player. His final task, something he picked up from Paul James, is to create a word-for-word pregame script, which includes blanks for his broadcast partners to fill in with their parts.

As they travel to games, Lyons drills Wrubell on his memorization of the opposing team. Lyons calls out a number, and Wrubell has to say the player’s name (pronounced correctly), the position, and a few relevant stats about the player. For football there may be as many as 70 opponent players to memorize each week. “If we miss one along the way,” says Lyons, “we have to start over. I’m sure there’s nobody else that does that in their preparation.”

“The parts I can control, I want to control,” Wrubell says. “Once kickoff happens it’s seat of your pants for the next six hours.”

Only when his mind is brimming with names, faces, formations, and stats does Wrubell feel ready to don the headset and let the art take over. Head football coach Bronco Mendenhall, whom Wrubell interviews on the air each week after games and on weeknight coach’s shows, speaks in superlatives when comparing Wrubell’s craft with that of other media representatives: “Greg is the most quick-witted, he’s the most insightful, he’s the most prepared, he’s the most articulate, he’s the deepest thinker, and [he] is the most enjoyable to talk to.”

Yet Wrubell is always on the hunt for ways to improve. After each game, he’ll scour the audio to pick apart his performance. Maybe he didn’t give the score or time remaining often enough. Perhaps he used a phrase too often or he transposed a player’s name. A maddening mental quirk for Wrubell is a tendency to mix up his left and right. “Sometimes I give wrong directions on the air,” he says. “That’s not good.”

Describing the personality that underlies the Wrubellian quest for the perfect call, his broadcasting partners throw out words like driven, type A, high strung, frenetic. Wrubell throws in obsessive for good measure—especially as it relates to his broadcasting equipment. He says that the occasional substitute broadcasting partner will sometimes good-naturedly offer to help break down gear after the broadcast. “No, no, no,” Wrubell says through a forced smile. “I need to touch all of this stuff myself.”

Wrubell acknowledges that his OCD, always-on, amped-up tendencies need a counterweight (recall that oft-chucked pen). He finds yin to his yang in his longtime broadcasting partners. Where Wrubell is frenetic, Lyons is folksy; Durrant is mellow where Wrubell is manic. “They are the best partners for me,” he says, calling them both dear friends.

And they, in turn, say they appreciate his brilliant intensity. “He’s a genius,” says Durrant, “one of the smartest guys I know.” (But really, he adds, don’t touch his stuff.)

THE SPORTING LIFE

“How can I do it? . . . Can I do it? . . . If I can do it, I want to do it.” Wrubell says that each October his mind goes through this mental progression as he calendars the fall collision of football, men’s basketball, and, now, women’s soccer.

During those months, covering three games in 48 hours or less isn’t unusual. One year, he had a basketball game in Las Vegas on Friday night, flew to Provo Saturday morning to call an afternoon BYU-Utah football game, and was back in Vegas that night for another basketball matchup.

With the addition of soccer, double-headers are becoming more common. With pregame and postgame coverage, he may be on the air for 10 or more hours (made possible, he says, from years of strengthening his vocal chords and a stash of lozenges, sprays, and other elixirs for the throat). “I love those kinds of challenges,” says Wrubell.

For nine months, it’s an all-consuming job. When Wrubell is not calling or traveling to games, he’s hosting coach’s shows, prepping for games, and constantly tweeting. Calling it “borderline illness,” Wrubell sends out 30 or more detail-rich tweets a day, sharing stats, media clips, and insights with his following, 22,000 strong. At the outset of this year’s basketball season, he tweeted a haiku about each player (Born on the Bayou, / Found a home at BYU. / Frank Bartley the Fourth.).

“[Greg’s] no good to me from August to April,” Tauna teases, providing as evidence a still-in-the-box ceiling fan and five smoke detectors that need installing. Fortunately, she and their four children are major BYU sports fans (the oldest two daughters—Jocelyn [’17] and Caitlan [’19] are BYU students currently serving missions). “It’s OK—we love it. We’re used to it.”

To carve out space for family, Wrubell opens up his home office to studying children while he preps for games and he occasionally brings family along on road trips. And when basketball finally wraps up in April, they’re sure to schedule epic vacations for the spring and summer breaks.

It’s his job, but for Wrubell being the Voice of the Cougars is much more than making a living. While he’s a stickler for maintaining professionalism and some semblance of impartiality (he never uses we or us to refer to BYU), his loyalties are clear from the rise in his voice when the Cougars net a goal or make an interception or nail a long three-pointer. “When you’re into it as closely as we are,” he says, “it’s real. I think that’s what people like about the broadcast; they know that I’m invested in it. It’s a real thing for me.”

While highlights include BYU’s victory at San Diego State at the height of Jimmermania (“We just floated out of the arena,” he recalls) and bowl victories, he says his favorite memory may just come from one of BYU’s lowest points.

Following the 1-25 1997 season (when Wrubell first began calling basketball games), in 1998 the Cougar hoopsters were slogging through another tough year with only seven wins to show for their sweat and jammed fingers. Just to qualify for the WAC Tournament, they’d have to do the near impossible—sweep a road trip to New Mexico (where the Lobos owned a 44-game home-court win streak) and then the University of Texas at El Paso. After stunning the Lobos (and themselves) by running away with an 83–62 victory in the Pit, BYU capped off the trip with a triple-overtime victory against the Miners. “It was amazing,” remembers Wrubell. “It was a nine-win season that just felt like they’d won the whole thing.”

“There are games like that,” he says. “You’re just so linked with the fortunes of the team. You feel like you did it. It’s great—it’s my team.”