Making Arabic texts accessible to Western audiences, BYU’s Middle Eastern Texts Initiative fosters friendships across cultures and religions.

Daniel C. Peterson | Photo by Bradley Slade

Directly north of BYU’s LaVell Edwards Stadium, a large carved stone stands in front of the “translation house,” where two editors work for BYU’s Middle Eastern Texts Initiative (METI). On the stone, along with Brigham Young University, is inscribed bayt al-hikma, Arabic for “house of wisdom.” This may seem to suggest delusions of grandeur, but it is really a very deliberate historical allusion to the translation movement of early ninth-century Baghdad, in which Christians, Muslims, and Jews collaborated to bring Greek medicine, science, and philosophy into Arabic.

More than a millennium later, BYU is engaged in a similar exercise, fostering a collaboration of Christians, Muslims, and Jews to make ancient Arabic texts accessible in English. In the process, the project is building strong and important friendships.

Reading Arabic Thought

Although Islamic civilization was, for several centuries, arguably the most advanced culture on the planet, and although its philosophers, scientists, historians, poets, and scholars produced some of the greatest books ever written, very little classical Arabic or Persian literature is accessible in Western languages. Contrast this with the writings of the ancient Greeks and Romans: anyone who wants to read the dialogues of Plato, the plays of Sophocles, or Homer’s Iliad or Odyssey, and anyone interested in Virgil’s Aeneid, an essay by Cicero, or one of the Roman comedies that inspired Shakespeare, can easily buy translations of these and scores of other classical works at a neighborhood bookstore. The same cannot be said, however, for Islamic writings, either modern or classical—a fact that is especially ironic, and perhaps even somewhat dangerous, since understanding the Islamic world is certainly an urgent priority for us today.

In the early 1990s some of us at the university began making plans for a major effort to translate Islamic texts. As has happened repeatedly in this project since that time, essential resources appeared with uncanny timing in surprising ways. Generous donors stepped forward to help launch the project, and personal contacts led to the acquisition of the finest Arabic word-processing software in the world at the time.

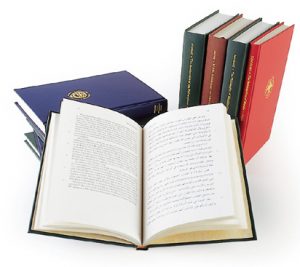

BYU’s Islamic Translation Series (ITS) published its first book, al-Ghazali’s wonderfully titled but somewhat difficult 12th-century Incoherence of the Philosophers, in 1997. Since then, it has published five other books, including a meditation (titled The Niche of Lights), also by al-Ghazali, on the so-called “Light Verse” in the Qur’an, and a discussion by the great Aristotle commentator Averroës (Ibn Rushd) on the relationship between faith and reason (The Decisive Treatise). A seventh volume is coming from press this summer: the massive Metaphysics or “Theology” of Avicenna (Ibn Sina), often considered the greatest of all Muslim philosophers, will perhaps be our most important book yet.

Once the ITS began to gain notice worldwide, other scholars approached us with ideas, and we expanded our focus beyond Islam. Moses Maimonides, universally considered the greatest Jewish thinker of the Middle Ages, was both an eminent philosopher and a leading rabbinic authority. Less known, however, is the fact that this pillar of the Egyptian Jewish community was also a distinguished physician and the author of numerous treatises, in Arabic, on the medical science of his day. When Gerrit Bos, of the Martin-Buber-Institut für Judaistik at the University of Cologne, in Germany, approached us with the idea of publishing dual-language editions of those works, we could not let the opportunity pass. Thus far, two volumes have appeared in the Medical Works of Moses Maimonides series.

Finally, it seemed necessary, if we wanted a complete picture of the region of the world with which we were dealing, to include the rich legacy of Near Eastern Christianity. After all, Christianity is not a Western or European religion. It originated not in Rome or Canterbury but in the Near East, and faithful Christians have lived, thought, and written there from earliest times. Yet these “oriental Christians” are often forgotten, and their writings are little known among their cobelievers in the West. We have now published our first dual language volume in the Eastern Christian Texts series, a marvelous little text on how to develop good character, The Reformation of Morals. An English-only series called the Library of the Christian East, under the editorial direction of David G. K. Taylor at the University of Oxford, will soon join it.

Collectively, these various series constitute the Middle Eastern Texts Initiative. The books are published by Brigham Young University and are distributed via the University of Chicago Press.

Creating Fruitful Conversation

METI is winning friends for both The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Brigham Young University. It involves international scholarly collaboration at the highest levels; our translators and advisors represent a variety of schools, including the University of Toronto, Oxford, Cambridge, New York University, the University of Hamburg, the Catholic University of America, Georgetown, UCLA, Harvard, Bar-Ilan University in Israel, and the State University of New York.

Additionally, 10 gala dinners have been held to celebrate the publication of the books, including events at the embassies of Jordan and Egypt, the United Nations, and the British Library in London. Among these were dinner-symposia, attended by cabinet ministers, prominent scholars, and others, in Cairo, Egypt; Amman, Jordan; and Damascus, Syria.

Former BYU president Elder Merrill J. Bateman participated in all of these events, and most of them also involved a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. On May 12, 2003, a symposium was held at the Library of Congress under the title “First Renaissance: The Scientific Legacy of Ninth Century Baghdad,” in connection with METI’s work in the history of science.

With our translations of Arabic texts, we are trying, in our small way, to bring the West and the Islamic world into fruitful conversation. Photo by Michael Stanfill.

Finally, METI’s publications have gained an international and multicultural readership that, I confess, I had not envisioned when I first thought merely of making great Islamic books available to Western readers. I still treasure a note handed to me by three chador-clad university coeds in Tehran, Iran, thanking BYU for the Islamic Translation Series, as well as a letter from a social worker in Jakarta, Indonesia, expressing his joy that, though he did not know Arabic, he could now read al-Ghazali—in English. Many other such stories could be related; METI volumes have been presented by Church and university leaders and others to dignitaries worldwide and have been well received.

I am particularly pleased that METI involves Jews, Muslims, and Latter-day Saints and other Christians in its work. My good friend Muhammad Eissa will serve to illustrate this cooperation. When I took on increased responsibilities with METI, Professor Eissa agreed to come to BYU and teach in my place for six months. At one point during that time, concerned about insuring that the Arabic texts in our books be as nearly flawless as possible, I asked him whether he had ever done any editing. He replied that he had grown up, literally, above a print shop in Cairo and had been proofreading and editing books since he was 14 years old. A PhD graduate of Cairo’s centuries-old, world-renowned al-Azhar University, the most prestigious Islamic institution of higher learning in the Arab world, Eissa is now back home in Chicago, but he continues to help us edit our books. He is personally committed to guaranteeing that our Arabic volumes—whether written by Muslims, Christians, or Jews—represent the most accurate versions of these texts that have ever been published, even in their original language. And his name suits such an ecumenical enterprise perfectly: Muhammad Eissa is the Arabic equivalent of Muhammad Jesus. (Only Moses is lacking.)

We are trying, in our small way, to do what was done in Baghdad in the ninth century: to bring the West and the Islamic world into fruitful conversation. And we are doing it, once again, by involving people of widely different faiths and backgrounds. I am proud of that. I hope that it illustrates that what once was can be again, that the strife, hostility, and mutual distrust that currently exist between Muslims and the West need not always dominate. I am humbled and moved that Latter-day Saints can play such a role. Building bridges is exactly the kind of thing, I believe, that a Church university should do.

Daniel C. Peterson is a professor of Islamic studies and Arabic. He is also an associate executive director of BYU‘s Institute for the Study and Preservation of Ancient Religious Texts, of which the Middle Eastern Texts Initiative is a part.