Now in nearly 200 countries and territories, BYU Television is attracting BYU fans the world over.

When you shake José Antonio Robles’ hands, you know he makes a living with them. As a cable installer, Robles digs, crawls, and drills through dirt, masonry, and concrete to hook up cable television for those who can afford it in the small coastal city of Huacho, Peru.

When you shake José Antonio Robles’ hands, you know he makes a living with them. As a cable installer, Robles digs, crawls, and drills through dirt, masonry, and concrete to hook up cable television for those who can afford it in the small coastal city of Huacho, Peru.

The city is nestled beside the Pacific Ocean about 100 miles north of Lima, Peru’s capital. In and around Huacho a concentrated Latter-day Saint population thrives: nine wards and three branches in one stake, wherein Robles previously served as a high councilor.

At the time, Robles worked for Cable Color, one of two cable companies in town; naturally, he felt it was his duty to supervise the satellite setup at the stake center before general conference. Robles noted the specific parameters necessary to receive the signal, and later, back at Cable Color, he tried them out on his own. What airs on that satellite signal when general conference is not on, he discovered, is a continuous broadcast from a university supported by the Church—a broadcast that quickly became Robles’ secret guilty pleasure.

“I just kept it for myself. I would watch in the office whenever I wanted, as long as I wanted,” says Robles. He continued viewing the channel, personally edified, for about a year. And so, in 2002, BYU Television made its international cable debut: a channel watched by an audience of one.

Eventually Robles desired all in Huacho to have access to BYU Television. With a petition signed by 1,500 local members of the Church, he convinced the owner of Cable Color to carry the channel—all he needed was BYU’s blessing. And so John L. Reim (MBA ’92), then managing director of BYU Broadcasting, received his first correspondence from Huacho, an e-mail appeal from Robles the cable installer, high councilor, and BYU Television fan.

The university had long offered the channel free to any U.S. cable provider that would carry it. The folks at BYU Broadcasting were simply unaware that it was piquing international interest; they had made no efforts to promote the all-English channel outside the United States.

Yet in late 2003, when BYU Television aired publicly for the first time in Huacho, the Peruvian viewers didn’t seem to mind that the 51st channel in an otherwise all-Spanish lineup was broadcast entirely in English. Though most could not understand the language, there was content on this BYU channel they could not get anywhere else—symphonies, varieties of dance, sports other than soccer.

Soon enough, BYU Television had a following in Huacho; yet in the time it took Reim and Robles to secure the satellite channel in Peru, an even larger international viewer base was sprouting elsewhere in the world.

Almost all at once, through a variety of means and mediums, a real demand for BYU Television was growing worldwide, and in the space of a few short years, audiences in almost every country would know about the university in Provo.

Millions from a Missionary

Across an expanse of ocean, about the same time José Robles was tinkering with the BYU Television signal in Peru, the Church’s New Zealand/Pacific Island Area Presidency was lobbying to get the channel’s educational and spiritual content onto American Samoa’s airwaves. The deal with the Samoan cable company was already lined up. The dish pointing to the appropriate satellite, however, didn’t exist.

“We just didn’t have $20,000 to install a new satellite dish,” says Derek A. Marquis (BA ’88), the current managing director of BYU Broadcasting. “We really didn’t have $20,000 for channel expansion—period.”

Neither did Church members in American Samoa, a territory that reports 61 percent of its own living at or below poverty level. But rumor had it there was a Church member from Arizona with a disposition toward the Samoan Islands—a man by the name of Rex G. Maughan (’62) who had served as a missionary there years before and had made significant philanthropic contributions to the islands since then.

It was hardly a pitch—when Maughan heard the proposition, he was more than agreeable. The founder and owner of Forever Living Products purchased the satellite dish, and in 2005, BYU Television went live in American Samoa. “That was the easy side,” Maughan says.

Easy side of Samoa, that is. Turns out Maughan served most of his mission in Western Samoa (now officially known as Samoa), not American Samoa; and he had to maintain his allegiance. At the time, there were only three public TV channels on the air in Samoa, all three controlled by the Samoan Broadcasting Company (SBC)—a government entity. But with a bit of finessing, and with the help of Joe Keil, a native Church member within the island nation’s government, there are now more than three channels airing on the SBC. Via the state-run SBC, BYU Television is now on the public airwaves in Samoa; Marquis says it is the only place in the world where you can pull the channel down with a set of rabbit ears.

“You drive around and you see them watching [BYU Television] in their thatched, open-air huts,” says Ruth Methvin Maughan (BA ’60), Rex’s wife. “It’s all that’s on!”

While the Maughans’ generosity stemmed from endearment to Samoa, there is now a line of countries in the Pacific waiting their turns. “Elder [Spencer J.] Condie (BA ’64) is after us weekly—‘Get it into New Zealand, into the South Pacific,’” Rex says. The demand is also swelling at the grassroots level; Maughan continually receives letters and phone calls from people throughout the Pacific. “Tonga is calling all the time, and Tahiti, too—once they heard that little Samoa had BYU Television,” he says. “We’re already looking at the next countries to put satellite coverage in, and we’re working diligently to get it to them.”

The Maughans’ affinity for BYU Television now matches their affinity for Samoa, and they’ve made generous contributions to prove it.

BYU Television International

BYU Television International

Thanks to those contributions, BYU Broadcasting launched BYU Television International on March 2, 2007, broadcasting content from BYU in Spanish, Portuguese, and English.

“It has been such a blessing to see BYU Television grow in English-speaking countries, and now to move it into Spanish and Portuguese,” said Elder Richard G. Scott, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, at the launch of BYU Television International. “It will be an edifying influence.”

BYU’s Board of Trustees approved BYU Broadcasting’s decision to launch the international channel due to the increased demand for translated content from BYU and the Church, as well as the rapid growth of the Church in Central and South America.

Now, one year after its launch, BYU Television International is available to more than 2 million homes in Latin America, reaching audiences in Mexico, Central and South America, and the Caribbean, as well as in Spain and Portugal. More than 60 Latin American cable systems currently carry the channel. BYU Television International is also reaching Spanish and Portuguese audiences in the United States, free to anyone with a backyard satellite dish. (The satellite coordinates to access the channel are now available at byutvint.org.)

Like its sister station, the international channel has 8,760 hours of airtime to fill each year, but BYU Television International is not a carbon copy of BYU Television.

“BYU Television International is fresh,” says channel manager Saul I. Leal (MISM ’06). “This is a bright and colorful and vibrant channel.”

The vivacious international channel fills those 8,760 hours with more dancing, music, performance, and sports, partly because those things translate easier. Programs are carefully selected with the international audience in mind; for instance, a cooking show hosted in an American, middle-class kitchen is not culturally sensitive or applicable to most Latin Americans. Podium programs, such as devotionals or other talks, are often infused with video clips to make the translated presentation more dynamic. Still, though much of the inspirational content on BYU Television carries over to BYU Television International, podium programs make up the smallest percentage of content on the international channel.

Ask Leal, and some of the best programs on BYU Television International are those that originate from campus. “There are so many beautiful things happening at BYU,” he says. “We need to export the smile of BYU students and the Honor Code, because that’s what the world needs.”

Now Streaming

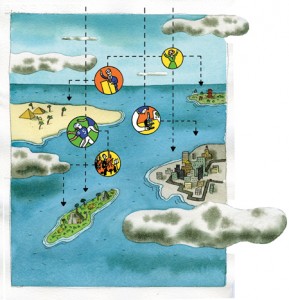

A giant map of the world, the full length of the sofa beneath it, covers one wall in Derek Marquis’ office, almost every country speared with tiny red, blue, or yellow flags. Each of the hundreds of flags represents the origin of a phone call, a letter, or an e-mail response to BYU Television or BYU Television International. But how did little flags end up in Holland, South Africa, and even China?

Through bleeding-edge technology pioneered by alumni John W. Edwards (BS ’87) and R. Drew Major (BS ’80) (a founder of Novell), both channels are available to anyone with an Internet connection, anywhere in the world. BYU Television and BYU Television International are the only TV channels on the Web that stream nonstop, day in and day out, with a reach that spans the globe.

“It’s a real power for TV that’s never been there before,” says Edwards, CEO of Move Networks, the company that hosts BYU Television on the Web. Move is at the forefront of the Web-television movement, with client-publishers like ABC, FOX, ESPN, and Disney—though not one of those networks maintains a station that airs online 24 hours a day, seven days a week. “They are thinking about it, dreaming about it,” Edwards says, “but BYU Television is doing it. The day is now; the technology is here.”

The technology functions a bit like on-demand TV: you can pause and rewind the live stream or access archived BYU Television and BYU Television International shows online at the click of a button at BYU Broadcasting’s Web site, byutv.org. Priced out, streaming both channels would cost BYU an estimated $1 million annually. BYU Broadcasting, however, receives the service from Move Networks free of charge. As Move’s first client, BYU landed a contract that was mutually beneficial: BYU received free server space, equipment, and tech services, and in return, Move Networks got content they could experiment with. Once Move had a viable example of what their Web technology could do, they showed BYU Television off to potential clients.

“We are now a major broadcaster because our company got to experience everything with BYU Television first,” says Edwards. “Take general conference: that opportunity allowed us to put a live broadcast into the hands of a mass audience.”

The most-watched program on BYU Television, general conference first streamed online through Move Networks’ servers in April 2006, garnering hundreds of thousands of unique user sessions. By tracing the IP address of each Internet viewer, Move can see instantly where the audience is located; the online audience watching Move’s first general conference broadcast was spread across 80 countries worldwide. Last October viewers in nearly 150 countries enjoyed general conference online. Today BYU Television has audiences in almost 200 countries and territories around the world.

In January that global audience was privy to a broadcast never before seen in their homes: the funeral of a prophet.

“Thank you for the coverage of President [Gordon B.] Hinckley’s funeral service [and] the installation of President [Thomas S.] Monson,” Kevin Jackaman wrote from Australia. “Being able to view all this in real time has been a real blessing.”

Selva Morixe of Uruguay added, “We have watched the funeral of our beloved prophet . . . and we watched it from our home.”

BYU Broadcasting received hundreds of e-mails expressing gratitude for airing the funeral online—a service Move Networks is pleased to make possible. Wholesome and meaningful programming trumps all the incentives Move has to offer BYU Television and BYU Television International online.

“Just like BYU Television, we’re interested in getting good, family-centered content out on the Web in an increasing, ample supply,” says Edwards. “There’s already plenty of content on the Internet that we wish was never there.”

The Content Philo Always Wanted

The Content Philo Always Wanted

Back in Huacho, Peru, José Robles is still installing cable, but now the requests come in for BYU Television International—a channel broadcast in his native language, piped into homes via Cable Color and the Internet.

“It is such a joy to receive the channel in Spanish,” says Robles. “It gives me satisfaction knowing that not only the members of the Church are benefiting from this, but also the nonmembers.”

With Robles as their guide, Derek Marquis and a group of BYU Broadcasting representatives visited viewers in Huacho before the international channel launched. They encountered a Church member who had received BYU Television and wanted her children to recognize the prophet’s voice—even if it was in English. They bumped into the missionaries, who said the channel gave them recognition and credibility. “They’d enter a home and say, ‘We’re the church that’s on channel 51,’” relays W. Lincoln Watkins (AA ’82), a Spanish translator and BYU donor who accompanied the BYU Broadcasting group. They also met with the owner of Cable Color. “He absolutely loved the channel,” says Watkins. “It adds a whole new dimension to his lineup.” From their conversation, Watkins ascertained that it is BYU Television’s rich content that makes the difference—the ability to bring a BYU orchestra or symphony into a Peruvian home.

It is, in the end, a fulfillment of what Philo T. Farnsworth (’27) had in mind when he invented television. “Symphonies would mean more when one could see the musicians as they played,” Philo once told his wife, Elma—or “Pem,” as he called her—as recorded in her memoir. In his days at BYU, Philo played first violin in the BYU Chamber Music Orchestra. Years after he passed away, when Bradley Creer, a BYU Broadcasting volunteer, personally installed BYU Television in Pem’s home, the first thing that came on her screen was a BYU orchestra. Tearing, Pem shifted her eyes to the ceiling and softly confirmed: “This is what Philo always wanted.”

“There is an audience out there craving this type of content,” says Marquis, “whether they have a connection to BYU or not. They resonate with the feeling they get when they’re watching.”

Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

New Building, New Content

BYU Broadcasting is inundated daily with requests for more content via more avenues of technology. But how can a nonprofit TV station that operates out of a warehouse in south Provo on a minimal budget better broadcast the BYU experience to the world?

For starters, they’re moving to campus.

For more than 25 years, BYU Broadcasting has operated out of a chain of buildings stretching from the Harris Fine Arts Center all the way to Springville, Utah. But last fall, BYU’s board of trustees granted approval for the station to begin fund-raising for a new home. The proposed multi-million-dollar building would straddle the hill east of the Marriott Center and north of the Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum, merging all of BYU Broadcasting’s studios and offices under one roof.

“Frankly, it’s difficult to reveal campus when you’re not on campus,” says Derek A. Marquis (BA ’88), managing director of BYU Broadcasting, speaking from the station’s epicenter—a warehouse located 4.5 miles south of campus. Acquired by the university in the early ’80s, the warehouse was intended to provide a temporary home for BYU Broadcasting.

The station’s master control, Marquis says, under normal capacity, would accommodate one TV channel. At present it’s pumping out eight TV channels if you count the digital side channels—not to mention five radio stations. Aging cameras and lines of wires are held together in some places by duct tape, and most, if not all, of the equipment will be obsolete when a 2009 federal mandate requires all TV channels to be broadcast digitally. “While the university has been supportive of its radio and television channels, there has just never been a facility retrofitted to accommodate TV production,” says Marquis, “and certainly not one prepared for the digital world we’re going into.”

The proposed facility, he says, will allow BYU Broadcasting to expand and adapt to emerging technologies. “Broadcasting today is done with computers, where even five years ago it wasn’t,” he says. “The other day, I was in the Salt Lake Airport, and the guy next to me was watching TV on his cell phone. BYU Broadcasting needs to prepare to deliver content the way viewers want to receive it.”

With the help of BYU President’s Leadership Council cochair Kevin B. Rollins (BA ’83), former CEO of Dell, BYU Broadcasting is creating a blueprint that will equip the organization with the digital infrastructure necessary to enter the next generation of communications.

“We need to erect a building with the future and the Internet in mind, versus what the last 50 years of television might suggest,” says Rollins. “There are already large parts of the world where more people own computers with Internet connections than TVs.” The new building will increase space for servers and other technologies. BYU Television and BYU Television International already stream online continuously to a global viewer base—and demand for content from BYU and the Church has never been greater.

To better meet the demand for fresh content, Marquis has recruited Sterling G. Van Wagenen (BA ’72), cofounder of the Sundance Film Festival and director of the second and third The Work and the Gloryfilms.

“We need new content, and we can’t get it fast enough,” says Van Wagenen, citing a program he produced 20 years ago that still airs regularly on BYU Television. Last year, BYU Broadcasting produced about 300 hours of original content—a drop in the bucket when compared to the nearly 9,000 hours that need to be filled each year on each of BYU’s TV channels. Yet Van Wagenen has made a notable difference; this year, almost 10 new series produced by BYU Broadcasting will go on air, and Van Wagenen has several documentaries in the works.

“What you’re seeing now is a richer and fuller palette of programs,” says Marquis—a vast improvement from the four-hour continuous loop of programming that BYU Television launched with in 2000. Back then, Marquis says the channel was largely “podium television”—talks, conferences, and forums were the easiest things to produce. Today, BYU Broadcasting has outstripped even the most grandiose expectations imagined by those who pondered BYU’s first TV channel. For now, a small warehouse on the outskirts of Provo is revealing BYU to the world

New Programs Airing in 2008

• Writer’s Block: a series of dramas and comedies based on original scripts written by BYU students

• Messiah: Behold the Lamb of God: a seven-part series on the life and mission of the Savior

• Questions and Ancestors: a new season of BYU Broadcasting’s genealogy series

• LDS Lives: a biography series highlighting the lives of well-known and not-so-well-known Latter-day Saints

• Road to Zion: a new season of the Church history travel show, with episodes in Hawaii, England, and France

• Real Families, Real Answers: a new 16-episode series following real families through challenges they face

• The Joseph Smith Papers Project: a series of documentaries on the largest publishing project in Church history

• Dance Special from Preparatoria Benemérito de las Américas: a series of dance programs filmed at the renowned Church-owned high school in Mexico

Their Channel

“¡Remolachas!” asserts Fernando Dealba (’08) of Spain.

There are students from 10 Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking countries crammed in this room, and they are taking sides—depending on what Spanish word they use for beets.

“Betarragas,” counters Danella Zuzunaga (’08) of Peru, and the debate erupts. A flurry of Portuguese and Spanish is unleashed. “Fruits and vegetables are the worst,” says Zuzunaga, slipping back into English. She is in the middle of translating a show that will air on BYU Television International, and no matter how many words there are for the vegetable in Latin America, she must decide on one.

From translation to editing to distribution, BYU Television International is produced almost entirely by international BYU students like Dealba and Zuzunaga. They may not have come with broadcasting know-how, but they do bring one thing: a passion for Latin America.

The majority of the students are trilingual. Zuzunaga is quinti-lingual: she is a Spanish speaker at heart who is conversant in English and Portuguese and is ardently studying Chinese and Arabic at BYU.

Working in distribution, Marcos A. Lopez (’08) of Mexico uses his language skills daily. In a given shift, he’ll call cable companies in 15 different Latin American countries to assist a launch or to solve technical difficulties.

Over in editing, John D. Wilson (’10) may not hail from Latin America, but he served a mission in Brazil, and at BYU Television International, he has become an expert at syncing, as best he can, the now-muted English lips with Spanish or Portuguese audio.

Many of the voiceovers heard on BYU Television International are recordings of these student employees. It’s important, Zuzunaga says, to make the same facial expression as the character in the program when recording, to ensure the same voice inflection.

“It’s more than just a straight translation,” says Dealba. “It has to be spoken the way they would explain it.” Dealba is currently performing the last step in the production of a Gladys Knight special in Spanish, checking the dubbing, flow, and integrity of the translation. He is an expert at the process; at age 50, Dealba has worked more than 20 years in ESL teaching and Spanish translation, even serving as an interpreter at general conference. “I guess I’m doing it backward—work, then education,” says Dealba, now a full-time student at BYU.

According to Saul I. Leal (MISM ’06), the manager of BYU Television International who is originally from Venezuela, the diversity on staff makes the office a melting pot—and every biweekly staff meeting a “Latino party.” The biweekly meetings are potlucks, for which student staff members prepare their favorite traditional dishes. “We sit down to a meal and discuss what’s good or bad, and what needs to be done,” Leal says.

Twenty-one students work under Leal, and in his eyes, they are intrinsic to the success of the channel. “Every student here is the heart of this channel,” Leal says. “They are the creative mind.”