Learning from the lives of Henry Eyring, Willard and Rebecca Bean, Kim B. Clark, and J. Golden Kimball.

Henry J. Eyring’s (BS ’85) Mormon Scientist: The Life and Faith of Henry Eyring (Deseret Book; 330 pp.; $24.95) is a can’t-put-it-down biography of Dr. Henry Eyring (1901–1981), a dyed-in-the-wool Latter-day Saint and internationally acclaimed scientist who has been a vital force in harmonizing science and religion in Mormon thought. The author is the grandson of Dr. Eyring and son of President Henry B. Eyring, First Counselor in the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Henry J. Eyring’s (BS ’85) Mormon Scientist: The Life and Faith of Henry Eyring (Deseret Book; 330 pp.; $24.95) is a can’t-put-it-down biography of Dr. Henry Eyring (1901–1981), a dyed-in-the-wool Latter-day Saint and internationally acclaimed scientist who has been a vital force in harmonizing science and religion in Mormon thought. The author is the grandson of Dr. Eyring and son of President Henry B. Eyring, First Counselor in the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Henry Eyring was born in the Mormon colonies of Northern Mexico and took part in the 1912 Mormon exodus to Arizona. He earned BS and MS degrees at the University of Arizona and a PhD in chemistry at the University of California at Berkeley. He taught at the University of Wisconsin, was a research fellow in Berlin, and from 1931 to 1946 taught chemistry and directed the Textile Research Institute at Princeton University.

While teaching at Princeton, Eyring revolutionized the field of chemistry by publishing the Absolute Rate Theory—“one of the most potent forces to ever appear in Chemistry” (p. xvii). In 1946 he moved to the University of Utah, where he was dean of the Graduate School for 20 years. From 1966 until his death in 1981, Eyring was Distinguished Professor of Chemistry at Utah, presided over some of the world’s most prestigious scientific societies, and received many awards, including the National Medal of Science. In 1980 the University of Utah named its chemistry building after him.

Eyring, a preeminent man of science, was also a devout man of God and a stalwart Latter-day Saint. A member of the General Board of the Sunday School, he became an unofficial spokesman on matters of science. He asserted that any seeming conflicts between science and religion “are the result of incomplete understanding, an inevitability given our modest intelligence relative to God’s ” (p. 53). Still, he had little patience with scriptural literalists who dismissed, ignored, or denied scientific findings about such matters as the creation of man and the age of the earth, and he engaged in vigorous but respectful discussions with Elder Joseph Fielding Smith on those topics (pp. 45–47; 62–63).

Eyring’s books on science and religion, The Faith of a Scientist (1968) and Reflections of a Scientist (1983), influenced a generation of young Latter-day Saints. Eyring wrote, “There is, of course, no conflict in the gospel since it embraces all truth” (quoted in Mormon Scientist, p. 59). He often cited his father’s words: “I’m convinced that the Lord used the Prophet Joseph Smith to restore His Church. For me that is a reality. I haven’t any doubt about it. Now, there are a lot of other matters which are much less clear to me. But in this Church you don’t have to believe anything that isn’t true” (p. 4).

In The Faith of a Scientist, Eyring revealed “the simple philosophy that guides me”: “This magnificent universe operates according to an over-all plan.” He continued, “The Planner is so great that He can be, and is, interested even in me. Because of His interest, man is here according to a plan which is in accord with the divine purpose.” He concluded: “If I were you, I would get this master plan in mind, believing that if all the little things are done well, one by one, the big things will take care of themselves ” (quoted on p. 294).

A Lion and a Lamb (Spring Creek; 180 pp.; $14.95), by Rand H. Packer (BS ’70), is the well-told story of Willard and Rebecca Bean, who served an unprecedented 24-year LDS mission (1915–1939) in the Joseph Smith Sr. home in Palmyra, N.Y. This faithful pair was the means by which the LDS Church reestablished a presence in the community where the Restoration of the Church began. President Joseph F. Smith told Willard after a Richfield stake conference, “I am extending a call to you and Rebecca to serve as missionaries and caretakers of the Joseph Smith farm” (p. 5). He told the newly married couple, “live there, take care of the farm, and re-establish the Church in that area.” They did, and the 5-year call turned into 24 years, as the Beans persevered in becoming part of the Palmyra community. Willard’s fearless, bold pugnacity (he had been a prize-winning boxer) in defending the faith was complemented by Rebecca’s long-suffering gentleness, as this lion and lamb undertook to “make friends for Joseph Smith and the Mormon Church” (xiii) and gradually transform local ire into respect and admiration. Though never easy, the Beans’ long mission was exciting, eventful, and fruitful. The couple was instrumental in bringing the Hill Cumorah, the Martin Harris farm, and the Peter Whitmer farm under ownership of the LDS Church. Today the Church presence in the area, now graced by the beautiful Palmyra New York Temple, owes much to the Beans’ valiance in magnifying the charge given them by President Joseph F. Smith. They were the Church’s go-to couple for establishing the Hill Cumorah Pageant, maintaining the Sacred Grove and other Church properties, hosting a stream of visiting Church leaders, conducting guided tours, and feeding every Mormon missionary who passed through Palmyra over a quarter century. Author Rand Packer, a former CES teacher, is a grandson of Willard and Rebecca Bean.

A Lion and a Lamb (Spring Creek; 180 pp.; $14.95), by Rand H. Packer (BS ’70), is the well-told story of Willard and Rebecca Bean, who served an unprecedented 24-year LDS mission (1915–1939) in the Joseph Smith Sr. home in Palmyra, N.Y. This faithful pair was the means by which the LDS Church reestablished a presence in the community where the Restoration of the Church began. President Joseph F. Smith told Willard after a Richfield stake conference, “I am extending a call to you and Rebecca to serve as missionaries and caretakers of the Joseph Smith farm” (p. 5). He told the newly married couple, “live there, take care of the farm, and re-establish the Church in that area.” They did, and the 5-year call turned into 24 years, as the Beans persevered in becoming part of the Palmyra community. Willard’s fearless, bold pugnacity (he had been a prize-winning boxer) in defending the faith was complemented by Rebecca’s long-suffering gentleness, as this lion and lamb undertook to “make friends for Joseph Smith and the Mormon Church” (xiii) and gradually transform local ire into respect and admiration. Though never easy, the Beans’ long mission was exciting, eventful, and fruitful. The couple was instrumental in bringing the Hill Cumorah, the Martin Harris farm, and the Peter Whitmer farm under ownership of the LDS Church. Today the Church presence in the area, now graced by the beautiful Palmyra New York Temple, owes much to the Beans’ valiance in magnifying the charge given them by President Joseph F. Smith. They were the Church’s go-to couple for establishing the Hill Cumorah Pageant, maintaining the Sacred Grove and other Church properties, hosting a stream of visiting Church leaders, conducting guided tours, and feeding every Mormon missionary who passed through Palmyra over a quarter century. Author Rand Packer, a former CES teacher, is a grandson of Willard and Rebecca Bean.

Armor: Divine Protection in a Darkening World (Deseret Book; 282 pp.; $21.95), by Kim B. Clark (’74), is the inspiring account of one man’s personal quest for deeper spirituality and stronger testimony. Clark, former dean of Harvard Business School and current president of BYU–Idaho, discovered course-changing inspiration in Paul’s admonition to the Ephesians (6:10–17) to “put on the whole armor of God.” Responding to President Gordon B. Hinckley’s repeated charge to stand firm and hold back the world, and his promise that, “If we do so, the Almighty will be our strength and our protector, our guide and our revelator” (Ensign,November 2003, p. 83), Clark resolved to apply Paul’s principles and precepts and enlisted his family in the effort. In this very personal yet widely applicable book, Clark tells of his discoveries and adventures in putting on the whole armor of God. He shares how turning wholeheartedly and determinedly to the Lord has blessed him and each member of his family as they have struggled to put on covenants, to arm themselves with the gospel, “to stand firm and fast, to not be moved, to not fall, to stand as a witness, and to be a standard to the world”

Armor: Divine Protection in a Darkening World (Deseret Book; 282 pp.; $21.95), by Kim B. Clark (’74), is the inspiring account of one man’s personal quest for deeper spirituality and stronger testimony. Clark, former dean of Harvard Business School and current president of BYU–Idaho, discovered course-changing inspiration in Paul’s admonition to the Ephesians (6:10–17) to “put on the whole armor of God.” Responding to President Gordon B. Hinckley’s repeated charge to stand firm and hold back the world, and his promise that, “If we do so, the Almighty will be our strength and our protector, our guide and our revelator” (Ensign,November 2003, p. 83), Clark resolved to apply Paul’s principles and precepts and enlisted his family in the effort. In this very personal yet widely applicable book, Clark tells of his discoveries and adventures in putting on the whole armor of God. He shares how turning wholeheartedly and determinedly to the Lord has blessed him and each member of his family as they have struggled to put on covenants, to arm themselves with the gospel, “to stand firm and fast, to not be moved, to not fall, to stand as a witness, and to be a standard to the world”

(p. 16). Clark’s account of the challenging journey of one family moves the reader to awake, arise, don the armor of God, and pursue his or her own journey to salvation.

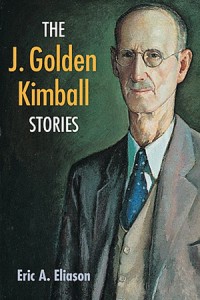

The J. Golden Kimball Stories (University of Illinois Press; 186 pp.; $20), by BYU folklorist and associate professor of English, Eric A. Eliason (BA ’92), is a laugh-aloud collection of orally circulated jokes and anecdotes that Mormons tell in homage to the legendary J. Golden Kimball (1853–1938), the colorful Mormon folk hero whose “slightly subversive but basically benign humorous behavior ” (p. 10) has made him the stuff of legend.

The J. Golden Kimball Stories (University of Illinois Press; 186 pp.; $20), by BYU folklorist and associate professor of English, Eric A. Eliason (BA ’92), is a laugh-aloud collection of orally circulated jokes and anecdotes that Mormons tell in homage to the legendary J. Golden Kimball (1853–1938), the colorful Mormon folk hero whose “slightly subversive but basically benign humorous behavior ” (p. 10) has made him the stuff of legend.

Eliason describes Kimball’s rise from mule skinner to the First Quorum of the Seventy, where he spent 46 years preaching the gospel in his high-pitched, squeaky voice. Kimball became notorious for his mild expletives, a colorful carryover from mule-skinner days. Such spontaneous profanity, which would have been overlooked in the barnyard or on Main Street, became delightfully ironic when spilled out in the presence of such dignified men as LDS Church president Heber J. Grant.

Eliason points out that the humorous stories that have gathered to Kimball like a magnet do more than merely give license to the profane and discomfit the straitlaced. J. Golden stories are also about teaching listeners “to get right with their God and obey church teachings” (p. 43). His genius lay not only in getting attention by his turns of phrase, dramatic pauses, and swearing, but in his witty “dispensing [of] sudden and audacious truths, and concise insight provided in clear, humorous language” (p. 34). For Latter-day Saints, then and now, his humor was therapeutic, permitting the Saints to laugh at themselves with a self-deprecation that shows maturity, enables insight, and blunts “stuff-shirt prickliness” (p. 23). And, (squeaky voice) dang it all, that’s always good for a laugh!

Richard H. Cracroft is BYU’s Nan Osmond Grass Professor in English, emeritus.