By Jeff McClellan

The center gallery of the Harris Fine Arts Center had taken on a new look. From the pillars around the gallery hung long red and blue banners proclaiming, “Lighting the Way,” and on the floor, surrounding the long, colorful tables filled with food, were displays presenting BYU’s case for raising a quarter of a billion dollars.

It was the public announcement of BYU’s capital campaign, “Lighting the Way,” and hundreds of university dignitaries, campaign volunteers, and friends of the university filled the HFAC for the gala celebration. In addition to many well-known university supporters, those in attendance were graced by a who’s who of the LDS Church: President Gordon B. Hinckley, two Apostles, the presidents of the Relief Society and the Young Women, three members of the Seventy, the entire Presiding Bishopric, and BYU’s resident General Authority, President Merrill J. Bateman.

When President Bateman addressed the throng during the ceremonies, it was apparent the new president had already adopted the campaign goals as his own. Coming into the six-year campaign when the two-year quiet phase was nearly finished, President Bateman was not only embracing the goals and vision of his predecessor, the late Rex E. Lee, he was expanding them.

All of this caused me to ask several variations of a one-word question: why?

Why would BYU go to such lengths to deck out the HFAC? Why would so many dignitaries—some directly affiliated with the university, some not—attend the program? Why would President Bateman so readily assume responsibility for his predecessor’s dream? Why $250 million? Why BYU?

Over the next few weeks, I asked that last question often. I asked it to university presidents, to people who never went to college, to multimillionaires, to generous donors in their humble homes, to people who aren’t members of the LDS Church. “Why BYU?” I asked over and over. “Why are you supporting this cause?”

As I heard their answers and saw their conviction, I began asking myself a similar question. “Why not BYU?” I pondered. “Should I be doing more?”

The words BYU’s $250 million capital campaign usually appear in the company of another word: ambitious. But the campaign is not nearly as ambitious as it would have been had plans gone as President Rex Lee originally desired.

M. McClain Bybee, BYU’s assistant advancement vice president for development, oversees all fund-raising at BYU. As Bybee tells the story, at the beginning of President Lee’s administration in 1989, the president invited Bybee in for a weekly meeting and informed the development officer that he would like to raise $1 billion during his presidency at BYU. Bybee now attributes his abundant white hair to the resulting shock.

In the 1980s, President Jeffrey R. Holland had conducted what many considered an ambitious campaign for BYU—$100 million. And here was President Lee saying he wanted to times that amount by 10. Having been in meetings with the presidents of major universities that were raising $1 billion or more, President Lee thought, why not BYU?

Bybee took a gulp and plunged in. Over the next few years, Bybee’s staff and the staff of the LDS Foundation, the parent organization of BYU Development, took President Lee’s dream and worked to make it a reality.

When the dust settled, what emerged was a six-year campaign headed up by three volunteer co-chairs. The three men—Alan C. Ashton, founder of WordPerfect; Hyrum W. Smith, president and CEO of Franklin Quest; and Jack R. Wheatley, a prominent real estate developer in northern California—serve as advocates for the university and direct the efforts of the nearly 90 other volunteers who are soliciting gifts ranging from $25 to $25 million from hundreds of thousands of donors.

Campaign Executive Committee, January 1996. Top row, left to right: Hyrum W. Smith, President Rex E. Lee, Alan C. Ashton, Jack R. Wheatley. Bottom row: President Merrill J. Bateman, President Eric B. Shumway

At the center of the campaign are three goals, defined by the board of trustees, which encapsulate the university’s direction as it heads into the next century. The goals are, first, to teach more students; second, to enhance the educational quality of the school; and third, to extend BYU’s influence around the world. As the vision of the campaign progressed,

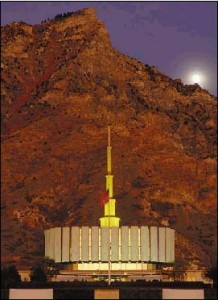

it grew to include BYU–Hawaii as well as BYU–Provo as it became more clear that this is one university with two campuses.

Through all the refining of the campaign, President Lee’s original plans were modified a little. After careful evaluation of BYU’s fund-raising history and the resources of the school’s constituency, the campaign goal was trimmed to one-fourth the president’s initial objective, a goal that is still a healthy sum. In addition, the six-year campaign didn’t start until two years before the end of President Lee’s administration. But for President Lee, two years were enough to get a lot accomplished. By the time his administration ended, more than half of the $250 million campaign goal had been raised.

“I’ve never worked with a man who had as much enthusiasm and as much courage and as high a level of commitment as Rex Lee,” says campaign director Barry B. Preator, who is also the director of support services for the LDS Foundation.

When I met BYU–Hawaii President Eric B. Shumway in the BYU Museum of Art prior to President Bateman’s inauguration, I sensed a little of his enthusiasm as he greeted me with a firm handshake, a warm smile, and “Aloha!” before he even knew my name. As we talked the next day, I sensed his love for this university and its two campuses when he told me that one of the joys of his position is telling the story of BYU–Hawaii.

“We’re talking about the spirit,” he said. “When people hear the story, understand the program, and meet our students, then the spirit touches them. And to see that conversion—it’s almost like teaching the gospel. Because this university is part of the gospel.”

The tie of BYU to the gospel is strong, said President Shumway. “This is one of the major ways the Lord is unfolding the Restoration to the world. It is hard to overstate the value of Brigham Young University—Provo or Hawaii. You really can’t overstate it. It’s bigger than any of us, and it’s bigger than we really understand, except in glimpses. But in telling the story to people, I see those glimpses a little more clearly.”

When President Lee told Bybee he wanted to raise $1 billion, Bybee realized right away the university would need some help. The two approached Chicago-based Grenzebach, Glier, and Associates, a firm that currently consults on fund-raising efforts amounting to more than $6 billion.

Grenzebach’s president and CEO, John Glier, initially advised against using him as counsel for the BYU campaign, saying the university should look for

one of its own, a Church member who understood the unique nature of the school. But President Lee insisted that he wanted Glier—an outside viewpoint, someone who could look at the university and its organization and purposes objectively. Glier conceded, and President Lee got what he asked for.

In the first meeting Glier had with President Lee, Bybee remembers, “John said, ‘I’ll give you this check for $1 billion if you can tell me how it will be used at the university.’ President Lee said, ‘Oh, I don’t know how we would use it.’ And John said, ‘When you do, I’ll help you raise $1 billion.'”

That exchange began a lengthy and intense period of questioning, during which Glier, with his outside viewpoint, met regularly with President Lee and BYU Development staff members to ask some tough questions. “This campaign reaches right to the core of what BYU and Church education are all about,” says Ron Taylor, director of communications for the LDS Foundation.

In the Campaign Promotional Video, President Lee says, “I don’t think there’s any question in any of our minds about the final destiny of BYU…. how we get there is our immediate concern.”

The answer to one of the initial questions—how does private support fit into a Church-run and Church-funded institution—came when the LDS Church committed that the campaign would not diminish its support for the school. The committed support of the Church means that BYU’s continued existence is not dependent on the money raised in the campaign -no campaign funds will have to be used to pay the light bill, says Bybee; it will all go to improving the quality and effectiveness of the educational experience at BYU.

Beyond the issue of money, however, Glier probed into more fundamental concerns, like the university’s purpose and direction. Before beginning the campaign, the administration and campaign staff had to write a statement to make the case for BYU. The “case statement,” as it’s called, explains why BYU is worth $250 million of donors’ hard-earned money.

Through the process of writing the case statement, the questions went beyond the development officers and past President Lee’s desk all the way to the board of trustees, as the university developed a focus to guide it into the next century, says Taylor. The focus of the statement is integrated in the campaign’s three priorities: teach more students, enhance educational quality, and extend BYU’s influence.

But President Bateman is quick to point out that this refocusing is not a change in BYU’s fundamental direction. “The direction of the university was set 120 years ago,” he says. “And I don’t believe there have been major deviations along the way. There might have been a few minor twists and turns in the road, but the mission of the university was set by Brigham Young, and it’s been reaffirmed frequently by succeeding prophets.”

That mission, as stated in Brigham Young’s founding charge to Karl G. Maeser, is “not to teach even the alphabet or the multiplication tables without the Spirit of God”—to educate the mind and the spirit. And as stated in BYU’s mission statement, the mission is “to assist individuals in their quest for perfection and eternal life.”

While the new focus given by the case statement and the three priorities is not a change in the ultimate destination of BYU, it is what former LDS Church President Spencer W. Kimball spoke of in 1975: one of the hills the university must climb along the way. In the campaign promotional video, President Lee says, “I don’t think there’s any question in any of our minds about the final destiny of BYU. . . . How we get there is our immediate concern.”

Interviewing Warren Jones was one of the delightful moments of writing this story. A pleasant man who is somewhat retired from the company where he served as president and CEO, Jones now dedicates a lot of time, effort, and money to helping BYU’s capital campaign. Jones has served on the Marriott School of Management’s National Advisory council and on President Lee’s President’s Advisory Council. Now he’s a member of the campaign steering committee. As I talked with him, he spoke highly of BYU and the people here, and it was plain he loves BYU.

Interestingly, though, Jones is not a member of the LDS Church. Although he grew up in a small southern Idaho town in which the only church was LDS, he never became a member himself. And while some may question why Jones would be so heavily involved in supporting a cause that is so rooted in the LDS faith, he finds nothing peculiar about it.

“If you’re going to help somebody, you like to help something that you believe in,” he said. And BYU is definitely something he believes in. Having grown up surrounded by Church members, playing on the local Church basketball team, and later marrying an active member, Jones says he has always been close to fine members of the Church and to people who’ve been involved with BYU.

“I believe so much in what BYU’s goals are for education,” he said. “Take the theological aspect out of it, and it still has such outstanding principles that I think the world just needs more of—people who will conduct themselves with those kind of principles.”

Preparing for the campaign was not an easy task—in all, it took about five years and entailed a massive internal study as well as an external feasibility study with potential donors. The first step, begun in 1989 when Glier came on board as counsel, was an internal study consisting of two parts: a program audit and a needs assessment.

The program audit, which looked at every facet of the BYU Development office, showed that BYU was not yet ready to mount a major capital campaign and revealed changes among the staff and with the computer database that needed to be made.

But the major undertaking of the internal study was the needs assessment, an effort to determine the answer to Glier’s initial question to President Lee—what would the school do with $1 billion?

To answer the question, says campaign director Preator, in 1991 the campaign organizing crew asked each of the colleges, “If you had a wish list and an opportunity to have whatever you’d like to have, what would it include?”

Clayton S. Huber, dean of the College of Biology and Agriculture, says the only guideline he received was that the items on the list should be in line with the mission of the university. There weren’t even restrictions on the dollar amount. “That was left up to us,” he says.

“We met with all of our department chairs and the Benson Institute, the Bean Museum, and other groups and invited their participation so it was a college-wide effort,” Huber says of the process.

While the deans were compiling their lists, the development staff was taking a hard look at the feasibility of President Lee’s $1 billion goal. Could the university’s constituency actually donate that much money? Did the current rate of giving at BYU lend support to that lofty a goal? After careful analysis of these questions, a new goal was set at $300 million.

In the meantime, the colleges were working on their lists. And though the focus was on needs, in the end, Huber admits, “We had a wish list.”

So did the rest of the university. “The deans came back with a shopping list that totaled about $600 million,” recalls Bybee.

Over the next year, the academic vice president’s council took the list and slowly pared it down. “They went through the fire, in terms of boiling that down,” says Ron Taylor. “With each item, they looked at the questions of, ‘What is the mission of the university, and how does this help us accomplish it?'”

By the fall of 1993, the list had been whittled to $300 million, and the

items on the list had been grouped into seven campaign priorities. “Grenzebach, Glier then took those ideas and went out and met confidentially and individually with approximately 100 couples across the United States,” says Bybee. This process was the external feasibility study to test whether the priorities and goals of the campaign were of interest to the university’s potential donors.

The three-month study came back showing that BYU had a very high level of support among its constituents; the potential donors interviewed by Grenzebach were very positive about donating money to the university.

“The single greatest response we got back,” says Preator, “was that they wanted their children and their grandchildren to have a Brigham Young University experience. They valued that experience very highly.”

The feasibility study also revealed that seven campaign priorities were too confusing. In addition, Grenzebach’s recommendations based on the study said the university could probably raise about $225 to $250 million -but no more. These results sent the team back to the drawing board once again where the board of trustees and the administration further refined the campaign goals to $217 million. The projects were also regrouped from seven priorities into three.

“It was at that time,” Preator says, “that the board of trustees chose to issue their official statement of support for the campaign.”

The trustees’ statement of support came in the spring of 1994, but the refining and shaping process wasn’t over yet. In 1995, BYU–Hawaii became an official part of the campaign. The administration and faculty on the Hawaii campus went through a similar needs assessment process to that done in Provo, narrowing the priorities list there from about $35 million to $15 million, which was added to the total campaign goal. Another $15 million came in the form of programs for the Marriott School of Management, and when President Bateman took the helm, he added $3 million for the Religious Studies Center, bringing the goal to $250 million.

“The goals have evolved,” says Preator, “and they will continue to evolve. If a capital campaign is dynamic and if in fact it’s being successful, there’s a very good likelihood that the priorities will be adjusted and that the goal will be adjusted, because it’s not a static process. The campaign is about much more than just money. It’s about making this university a viable and living entity that is motivating and changing lives.”

Despite the gusting wind and the threatening clouds, a small crowd of students and administrators gathered at the base of Y Mountain one early evening this April to dedicate a set of plaques commemorating the Y. When Wesley J. McDougal, the outgoing president of BYUSA, addressed the huddled crowd, he told of a close Hungarian friend who saved enough money to attend BYU for one semester. He came, hoping for financial assistance to stay longer, but his prospects looked bleak.

As McDougal spoke with the student one day, the Hungarian expressed his gratitude for being at BYU. “I feel like I’m going from one temple to another temple,” he said of the buildings on campus. “I may be here only one semester, but I’ll learn, I’ll go to my religion classes, and

I’ll do everything I can so that I can partake of this spirit so I can go back to my people. I came here to learn so I could go back and teach.”

On another occasion, this student said, “My people will never come here, but they will taste of BYU through me, and I will go back and tell them what this Zion community is about. They will never go to the Marriott Center to hear a devotional. They will never have the prophet in their midst on a monthly basis. But I did. And I will go home and I will touch their lives because I was here.”

With the three priorities agreed on, the studies finished, and the support of the board of trustees given, the campaign got underway. Until now, however, the campaign has been in the “quiet phase.”

“I’m always interested in why it’s called ‘the quiet phase,'” said Hyrum Smith at the public announcement in April, “because I will tell you, the last two years have not been quiet.”

For those involved with the campaign, Smith is right. Although the campaign had not been discussed publicly, a flurry of activity was occurring in the background as the campaign staff sought the initial gifts and put together a volunteer organization to lead the campaign.

“This is a campaign for BYU not a campaign by BYU,” explains Bybee. “There’s a big difference. A campaign for BYU is carried out by volunteer leaders, who are alumni and friends, for the university. A campaign by BYU is the internal staff trying to carry it out.”

And although the LDS Foundation staff is not carrying out the campaign on its own, Preator says the staff plays a high-level support role in its partnership with the volunteers. “We have been guiding the whole process,” he says. “The staff does a tremendous amount of legwork.”

Doing legwork in the background is exactly where the staff wants to be, so the organizers designed a volunteer structure that would take the lead in the campaign. Consisting of an executive committee, a steering committee, and five gift committees, the volunteer organization includes about 90 men and women from across the United States.

The formation of the structure began about two years ago when President Lee recruited the three co-chairs. Along with the presidents of BYU–Provo and BYU–Hawaii, the co-chairs make up the campaign executive committee. Each of the volunteer co-chairs will serve a two-year term as the acting chair of the campaign, although they are all actively involved throughout the six years. Hyrum Smith was the acting chair for the first two years, Jack Wheatley is the current acting chair, and Alan Ashton will lead the campaign in the final two years.

Preator describes the role of the co-chairs as being three-fold: “First, to commit to significant gifts themselves, so that they have a testimony of the process; then to help recruit other campaign volunteers; and finally, to be advocates and spokespersons for the cause.”

The 15 members of the steering committee have a similar role to that of the co-chairs. In addition, from the steering committee have come the chairs and other leaders of the five gift committees: leadership gifts ($1 million and up), major gifts ($250,000 to $1 million), special gifts ($25,000 to $250,000), annual gifts (up to $25,000 annually), and corporate and foundation gifts.

“Our goal in the organization of the Lighting the Way campaign,” says Ashton, “was to get the very best people around us and working with us and working together. I think we’ve accomplished that.”

Many of the campaign staff point to the volunteers as the heroes of the campaign, and Preator says the co-chairs, in particular, have sustained his dedication to the campaign, even through the many meetings. “The co chairs are always present, they’re always involved. When we ask them to host a particular function, they’re very willing to do that and to give generously of their time as well as their means. It makes it a lot easier for me to be enthusiastic when I see their level of commitment.”

The volunteers’ commitment is attested by the fact that each of them has contributed financially to the campaign goal—an element that is a key to the whole campaign. “I think it’s parallel to the gospel,” says Bybee.

“I tell you, you can’t get the Lord in debt to you. You have asked how he’s blessed me – he’s given me 100-fold for every nickel that I’ve ever sacrificed for the BYU or building up the Kingdom of God.”

“How effective is someone to tell someone else about the gospel of Jesus Christ if they don’t pay tithing? If they don’t live the Word of Wisdom? And if they don’t sacrifice their time? They have no testimony, no advocacy.” If the volunteers have anything, it’s advocacy and testimony. As of the campaign kickoff in April, $140 million had been committed to the campaign. Of that amount, $77 million, more than half, came from the campaign volunteer leadership.

I was amazed at how closely the lives of Howard Barben and Merlin Sant parallel each other. Both men spent their childhood in southern Idaho in the early 1900s. In the 1920s, their families left Idaho, the Barbens going to West Jordan, Utah, and the Sants to Long Beach, Calif.—the places the two men would spend the rest of their lives. Both served missions for the Church but never had the finances to attend college.

Each had a career that provided a humble, but adequate, living for his family. They served as bishops and stake presidents and later as a mission presidents, Brother Barben in Alaska and Brother Sant in New Zealand. After their missions, they were called to be patriarchs in their stakes, and both are now sealers in their respective temples. In addition, both of them are reaping the fruits of wise investments and have given generously to BYU. And both men give all the credit to the Lord.

“Before we came home from our mission,” Brother Sant told me, “our son wrote us and said, ‘Dad, what are you going to live on when you return from your mission?’ I said, ‘Well, I have a pension, and I have Social Security, and I think the Lord will provide.’ Well, I have kicked myself several times for not keeping a total log on how well the Lord provided. It was only because of his kindness and goodness to us that we were able to do anything with BYU.”

“The Lord has blessed me. God has put me in a position to do things because I have a willingness to do them,” said Brother Barben. “I tell you, you can’t get the Lord in debt to you. You have asked how he’s blessed me- he’s given me 100-fold for every nickel that I’ve ever sacrificed for the BYU or building up the kingdom of God. The Lord is a marvelous paymaster. There’s no way you can get him in debt to you.”

Each of the two men has sacrificed much so he could donate to BYU. When I asked them why, they shared deep feelings of consecration, of devotion to the Church, and of gratitude to God. “It’s just in a sense of gratitude to our Heavenly Father that we have done these things,” said Brother Sant.

At the kickoff on April 4, the campaign officially entered its “open, loud, big-time phase,” as Hyrum Smith called it. The public phase, as it’s referred to officially, will end Aug. 31, 2000.

“The public phase is an opportunity to celebrate what’s happening at Brigham Young University, to teach what’s happening at the university, and to invite investment in the university on a broad scale,” says Preator.

With donations coming in both pledges and outright gifts, most schools kick off the public phase of their campaigns with about 30 to 40 percent of the total campaign goal raised, according to Glier. BYU’s campaign has been particularly successful so far, with 62 percent—some in pledges, some in outright gifts—raised during the two-year quiet phase. From here, the various committees will be pounding the pavement and seeking donations, which is not always an easy task, says Warren Jones, chair of the major gifts committee: “I think some people prefer to sit on their pocketbooks rather than open them up.”

The committees mostly work on a personal level with individuals who may be able to donate. “The whole set-up of the volunteer effort of this campaign is really quite simple,” says Carol B. Minor, chair of the annual gifts committee. “There’s nothing complicated about it at all. Our first responsibility is to set the example by making a gift ourselves. Then the primary task of each volunteer is to contact people and secure at least three gifts per year at the higher levels of his or her committee’s giving range.”

Through monthly conference calls and semi-annual meetings in Provo, the committees keep in touch with each other and with the staff at BYU, who help direct the various efforts.

“The campaign is a calendar-intensive kind of undertaking,” says Preator, explaining that the staff spends a good deal of effort matching schedules between the presidents of the two campuses, the three co-chairs, and the other volunteers.

For the next four years, the staff will be coordinating schedules for a variety of fund-raising efforts, including large regional celebrations, presidential weekends at BYU, and small cottage meetings around the country. In addition, the efforts of the annual giving program will include working with the various regional chapters of the Alumni Association.

The campaign committees will attempt to take their efforts everywhere and reach everyone who may donate to BYU; the campaign is not limited to alumni and members of the Church. Jack Wheatley says, “You search for those people who have a love for BYU, who believe in young people, who want to see a better education for the Church members and non-Church members here, who believe that the values which are espoused within the BYU education can be spread throughout the world.”

It doesn’t matter where those people are found—whether they are Church members or not or whether they attended BYU or not. “We’re reaching out to people and plowing new ground and planting new seeds for BYU that has never been done before,” Minor says.

The university is actually forced to reach out to such a wide range of potential donors because an estimated 656,065 people will need to be contacted to get 327,350 of them to donate to raise $250 million.

Those estimates come from the campaign gifting table, a document outlining how many gifts will be needed at what levels for the university to reach its goal. For instance, one donor needs to give $25 million, 90 donors need to give $250,000, 525 donors need to give $25,000, and 135,000 donors need to give $25. “Every single donor to this campaign has meaning,” says Bybee.

Wheatley agrees. “We need donations from the students just as much as we need donations from successful people with millions of dollars.” In fact, one may say that the small donors are needed more than the big donors—or at least more of them. According to the gifting table, 260,000 donors are needed in the combined lowest two gifting levels—$25 and $50—compared to 10 donors in the combined highest three levels—$25 million, $10 million, and $5 million.

Bybee puts the giving into perspective when he talks about how much LDS people already give. Most schools expect their alumni to give 6 percent of their disposable income to the school. At BYU, most of the alumni already give 10 percent of their entire income to the Church. And then there are fast offerings, missionaries to support, large families, children in school, and a multitude of other charitable donations. And then BYU asks for money on top of that.

“Anyone who makes a gift to this campaign is really appreciated,” says Bybee, “because we know what they’re doing. They really are generous donors.”

When I met with Ramona Morris and Beverley Nalder in the Orem home they share, I saw a living example of philanthropists—people who give for the love of people.

“Neither Bev nor I have children of our own, so we are kind of surrogate mothers,” said Morris. For the last three years, Morris and Nalder have sponsored a four-year scholarship to BYU, awarded to the top female Provo High School student each year. And Nalder has a BYU scholarship of her own which has helped three or four re-entry women each year for the last four years.

“During my years of counseling here at the Y,” explained Nalder, who spent 27 years as a counselor at BYU before retiring five years ago, “I would see a lot of these women who had married and had not finished schooling. And then they had divorced or their husbands had died, and there was no money for them to finish school.” Nalder’s scholarship now helps those women fund their education.

Morris, who was a counselor at Provo High School for 22 years, saw a need among young women who couldn’t afford an education but who showed real promise. “It was an opportunity to help some young people who otherwise would never have that chance,” she said.

The two women are dedicated to their scholarships and the opportunity to provide for others. When I asked how long the scholarships will continue, Nalder said, laughing, “Until we have to go on welfare!”

But at the same time, they each insisted it’s not a sacrifice. “As far as the money is concerned,” said Morris, “it is not a sacrifice. I’m willing to give it just to help others have some of the similar kinds of opportunities that we’ve had. We feel really fortunate in the good portion that we’ve received.”

“I don’t view it as a sacrifice,” said Nalder. “I’m driving an ’86 Honda, and I probably could have had a new car or I could have gone on a big trip. But I’m not hurting because I’m going without those things. It’s just a matter of seeing this as more important.”

Bybee likes to talk about “the sacrificial gift”—a gift that is difficult to give, no matter the size—the widow’s mite. Nalder and Morris are not high-profile executives who have donated millions of dollars to the university. They’re two former counselors who love people enough—and who see the value of BYU enough—that they’re willing to give whatever they can to help.

“They know it’s going to change lives,” said Bybee of Nalder and Morris. “They’ve been in education all their lives, and they want to be a part of it. They’re not the Hyrum Smiths or the Alan Ashtons or the Jack Wheatleys. But in terms of commitment—they’ve changed their lifestyle because of their donations to BYU. So has Alan Ashton. They’re on equal par.”

Despite the fact that this campaign will raise a quarter of a billion dollars for BYU, Ron Taylor insists that the BYU Development staff is not going to close up shop and retire in September of the year 2000.

“It’s just a beginning,” he says. “When the campaign’s over, the work will go on. We hope that people will understand more, that people will understand deeper, that people will appreciate more what the university is about and understand that in order for it to continue to be successful, we’re all going to have to continue to support it to whatever level we can.”

Preator says the purpose of a campaign is to raise the general level of giving to the university to a new height—a level at which the giving will remain after the campaign is over. “And the expectation is that not only will the philanthropic support be sustained at a higher level, but the programs of the university will be more excellent in some equivalent kind of way,” he says.

Although a lot can be done to raise the university to a higher level with $250 million, Bybee tells people not to get distracted by the large sum. “Translate it into what it is going to do to change people or save people’s lives,” he says. “It only has meaning once you do the translation.”

The translation starts with what the money will do for the university, where, as President Bateman says, “These funds will allow us to take major steps forward in the quality of the university. The university is committed to being more efficient, which will allow more students to enter and graduate. We fully expect to widen the university’s influence across the globe.”

Improvements in the quality of BYU and what it has to oVer will then be reflected in the lives of the students. “This campaign is not a whimsical gimmick to try to get into people’s back pockets more effectively,” says Taylor. “It really is about helping build the kingdom. It is about strengthening the university. It is about helping students achieve their potential. It is about giving students a chance who might not otherwise have a chance.”

It was the night before President Bateman’s inauguration. A friend and I were walking across campus, returning home after attending a BYU campus community reception for President and Sister Bateman. My friend, Karene Adams, would be walking through the graduation ceremonies the next day to receive her degree.

As we walked by the Harris Fine Arts Center, Karene told me how grateful she was to have been able to attend BYU. She felt she came for a purpose, she said; no one comes to BYU by accident.

I’m sure Wayne Belleau would agree. Belleau came to BYU in January 1967 from Laconia, New Hampshire, where he had been baptized a member of the LDS Church three months before. “For me, a new member of the Church, you can imagine how dramatic that was,” said Belleau. “I love that school because it really did change my life around. I got to see the bigger picture at a time in my life when it was really important.” Now Belleau is a donor to the university because he wants others to have the same experience and opportunity he had, because he’s so profoundly grateful for BYU’s influence on his life.

I feel a similar gratitude for BYU’s influence on me. I have a favorite piece of sidewalk on campus between the Maeser Building and the Brimhall Building. When the cement was poured for the sidewalk, some of the leaves from the trees fell on the still-wet cement. Now the impressions of the leaves remain. I love to walk along and look at the leaves in the cement—some perfectly formed, others harder to distinguish, but all of them firm impressions of leaves from years ago.

BYU made similar impressions on the still-wet cement of my life. It gave me an opportunity to learn in an atmosphere of faith—to learn not only of writing and editing and reporting, but also to learn of spirit and covenants and God.

At one time, not long before I graduated from BYU, I was frustrated because I felt like I was getting a degree and not an education. But then I realized that no one gets an education in four years. BYU, or any other university for that matter, cannot produce fully educated young people. An education is a continuing, lifelong process. I am not educated now, and I will not be educated when I’m 75, not if I read all the books in the library. That’s the beauty of it—our education will never end.

That is also the beauty of BYU—here at BYU I did not receive an education, but I received the foundation I need for an education that will never end. Unlike the secular foundations given by many schools, the cement of the foundation I received at BYU contains the impressions of things spiritual and temporal—impressions that will enable my education to continue eternally.

Why BYU? Because it has made a difference in my life. Because it has made a difference in Wayne Belleau’s life, in Karene Adams’s life, and in the lives of hundreds of thousands of others—many who have never been here but who have been blessed by those who have.

Why $250 million? Because, like the pioneers, we believe and we want to plant seeds for trees we won’t enjoy, but our hope and our faith is that others will enjoy those trees. And the leaves of those trees will fall on the still-wet cement of their lives and will make impressions that will last for eternity.