That’s How the Light Gets In

That’s How the Light Gets In

Along life’s mortal journey we embrace Christ’s healing power through our cracks and imperfections.

By Tyler J. Jarvis (BS ’89, MS ’90) in the Fall 2013 Issue

Illustrations by Raymond Biesinger

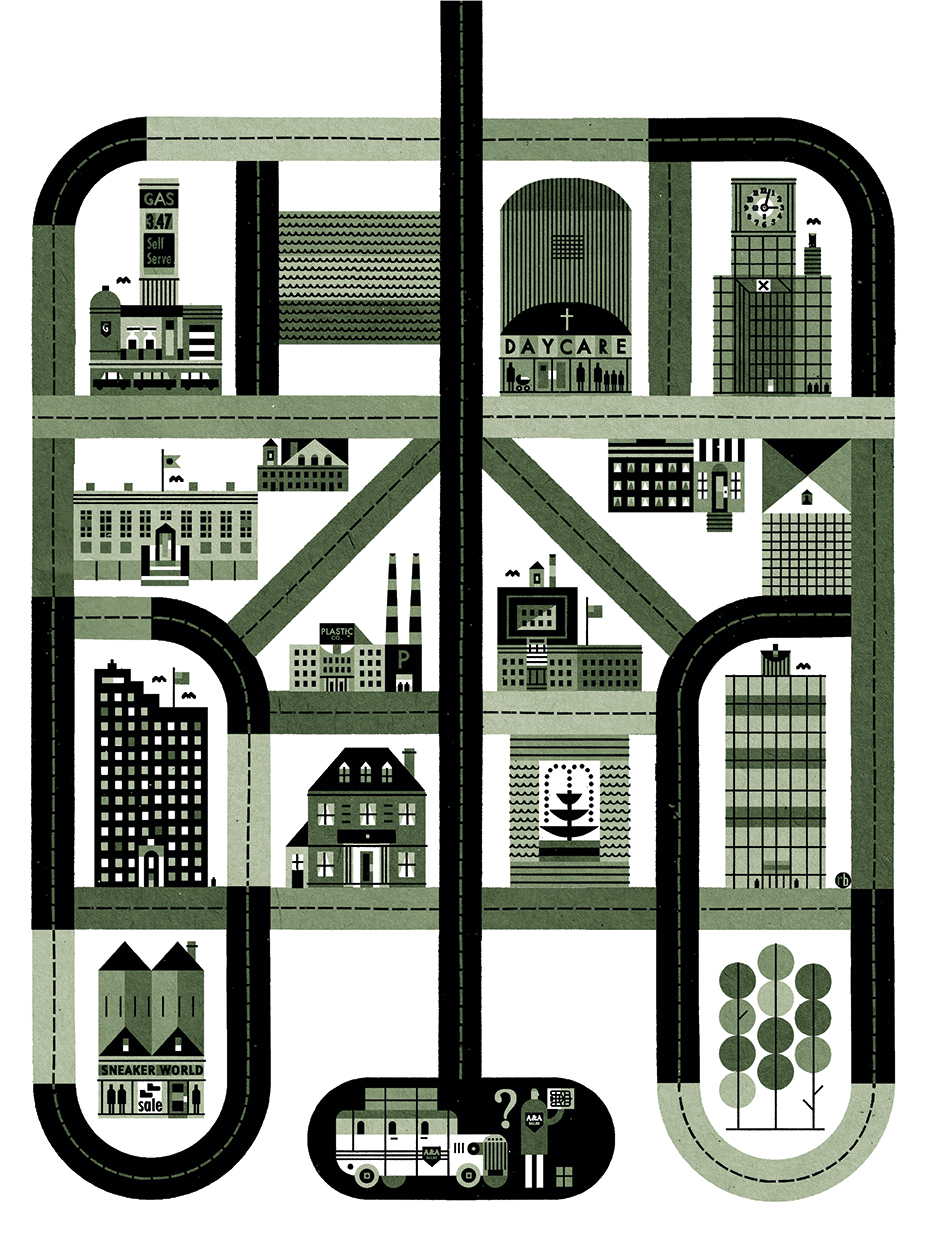

A traveller must visit many destinations to sell goods or make deliveries. Her problem is this: what route will be the fastest way to get to all the destinations? A poor choice could mean traveling many times farther than if she made a good choice.

This classic math problem is called the Traveling Salesman Problem, and it is very important to companies like UPS, the U.S. Postal Service, Walmart, and Amazon. For example, according to Wired magazine, UPS has roughly 55,000 delivery trucks running each day. If each driver could shave just one mile off the daily trip, it would save the company $30 million each year.1 And the Traveling Salesman Problem also has applications in computer chip manufacturing, DNA sequencing, and many other areas.

With only three destinations, the traveler has only six possible routes. To solve the Traveling Salesman Problem with three destinations, I just compare the six routes and see which is shortest.

With four destinations I must check a bit more: 24 possible routes. I can do that. With five destinations we have 120 routes. I am too lazy to check all those, but it is not hard to write some computer code to do it for me. Unfortunately, the number of routes to check is growing rapidly. For 10 destinations we have 3,628,800 possible routes to check—a lot, but not impossible.

For 20 destinations it grows to 2,432,902,008,176,640,000. This is a little too big for my laptop to check in any reasonable amount of time. In fact, if my computer could check a billion routes per second, it would still take 77 years to check all the possible routes. At current prices, just the electricity for the computation would cost roughly $675,000.

The point is, even for just 20 destinations we have way too many possible routes to check in any reasonable amount of time. The bad news is that in many real-life situations we have many more than just 20 destinations—for example, a UPS driver makes an average of 120 deliveries each day.

For 120 deliveries there are so many possible routes we couldn’t store them all in the memory of any computer in existence. In fact, if we had as many processors as particles in the universe, and if each processor could check a trillion routes per second, it would still take more than a googol years—that’s a one with 100 zeros after it—far, far more than the age of the universe.

The Clay Mathematics Institute in Cambridge, Mass., offers a $1 million prize for the first person to find an algorithm to solve the Traveling Salesman Problem in a reasonable amount of time.

Many other important mathematical problems suffer from similar difficulties—we can’t seem to solve them exactly because they are just too big. With such problems, as long as we insist on getting a perfect answer—the one and only very best solution—we are utterly paralyzed by the size and complexity of the problem. You could say we are paralyzed by perfection. So let me tell you how to become unparalyzed.

If we really want a good answer to many of these hard problems in a reasonable amount of time, we must make do with an approximation and admit some chance of error. I am something of a perfectionist, so this is difficult for me.

But if I am willing to accept an answer that is only close to the perfect one—as soon as I give up on perfection—something amazing happens. We can get a very good approximate solution to the Traveling Salesman Problem not just quickly, but blazingly, astoundingly fast. This approximate solution is not perfect, but it is very good.

Similarly, in our own lives, to avoid being paralyzed by perfection we must admit and accept imperfection. This requires honesty and humility. We can’t try to cover up our ignorance or our mistakes. We must admit them and learn from them.

In fact, I know only a few things perfectly: among those, that the Father and the Son live and love me and you, that the Book of Mormon is what it claims to be, and that this church is where the Lord wants me to be.

I also know, with a perfect knowledge, that for now, on this earth, we are all imperfect, both in knowledge and in performance, but that Christ’s Atonement can bring us to perfection if we allow it to. The first step to applying the Atonement is to admit and accept our imperfection.

Being a mathematician often forces me to admit what I don’t know. Julia Robinson, the first woman elected to the National Academy of Sciences and past president of the American Mathematical Society, was once required to submit a description of what she did each day to her university’s personnel office. This is what she wrote:

Monday—tried to prove theorem

Tuesday—tried to prove theorem

Wednesday—tried to prove theorem

Thursday—tried to prove theorem

Friday—theorem false 2

People like me usually need a lot more than a week to figure out our mistakes—and even more time to get the courage to admit them. And it is not only our knowledge that is imperfect. Just as the computer has limited ability to execute the programs given it, so we have limited ability to execute what we know we should.

To survive and succeed in this life we must admit and accept that imperfection and be patient and understanding with imperfection in ourselves and in others. As Elder Jeffrey R. Holland (BS ’65, MA ’66) said:

Be kind regarding human frailty—your own as well as that of those who serve with you in a Church led by volunteer, mortal men and women. Except in the case of His only perfect Begotten Son, imperfect people are all God has ever had to work with. That must be terribly frustrating to Him, but He deals with it. So should we.3

Sometimes perfection just isn’t possible in our finite, imperfect world. When my wife was a missionary in Germany, she and her companion decided they were going to keep all of the mission rules exactly. They got out their white handbooks and the additional list of rules for their mission and sat down with their blue planners to schedule everything into the week: wake up at 6:30 and then spend a half hour for personal scripture study, a half hour for companion scripture study, a half hour for exercise, and so on throughout the day. But somehow they couldn&rsquot make it all fit before their required bedtime of 10:30. They tried and tried but couldn’t get it to work. They only figured out why it was so hard to schedule when they added up all the time necessary to keep every rule each day—25 hours.

The realities of living in our imperfect world mean that we have no choice but to make do with an approximation—to admit and accept imperfection.

Accepting imperfection transforms many important mathematical and computational problems from being unsolvable in the lifetime of the universe to being solvable now on current, actual computers, but the solutions still require deep thought and hard work.

In the same way, admitting and accepting imperfection allows us to find imperfect but workable solutions to our personal and spiritual problems—but these solutions still require deep thought and hard work.

As the Lord told Oliver Cowdery after he had tried unsuccessfully to translate the plates: “You took no thought save it was to ask me. . . . You must study it out in your mind” (D&C 9:7–8).

And Brigham Young said: “Whatever duty you are called to perform, take your minds with you, and apply them to what is to be done.”4

Not long ago I had a student who told me he hated math and that he was no good at it. He was sure he would not understand the math in my class, and he was a little angry because he needed my class for some requirement or other. But with a lot of encouragement he reluctantly promised me he would do something he had not done before: he would not only answer all the homework exercises but would also make sure he understood all the steps in each problem, why that step was the right thing to do, and why it worked. He agreed to study it out in his mind.

At first this was painful to him—he really had to fight his frustration and impatience. He wanted to say, “Just tell me what to do and let me get this over with.” But he kept his promise. He read and reread the explanations in the book. He came to my office hours and asked me lots of questions about how and why things worked. He asked the TA many similar questions. And as he continued to work at it, he began to understand a little bit about how math works and why it is the way it is. Partway through the semester he confessed to me that he actually liked the class. By the end of the semester he not only earned a good grade in the class but was really excited about what he had learned. He even wanted to take another math class. He was no longer “bad at math.” His hard work and deep thought had transformed not only his attitude but also his ability.

But this is not easy. My former neighbor Eliot Butler said it well:

To learn is hard work. It requires discipline. And there is much drudgery. When I hear someone say that learning is fun, I wonder if that person has never learned or if he has just never had fun. There are moments of excitement in learning: these seem usually to come after long periods of hard work, but not after all long periods of hard work.⁵

But, like it or not, it must be done—hard work and deep thought are the only way. As the Lord said to Oliver, “You must study it out” (D&C 9:8; emphasis added).

It is not enough just to find an approximate answer to the problem. We must also act on that approximate,imperfect answer. That might scare you. It often scares me. But we cannot let our fear of imperfection, our fear of making a mistake, prevent us from acting.

As Paul told Timothy, “God hath not given us the spirit of fear; but of power, and of love, and of a sound mind”(2 Tim. 1:7).

When I went to graduate school many years ago, I was lucky enough to be admitted to a school with some famous faculty members. One of them was especially impressive. He was a Fields medalist—the nearest thing in mathematics to a Nobel Prize winner. Other students spoke of him with awe, both because of his brilliance and because of his reputation for criticizing students. When I heard how he had berated a student for being both lazy and stupid, I determined that I would never give him cause to criticize me like that. I decided never to ask him for advice or help until I had exhausted every other means for solving a problem. The result was that he never criticized me, but I also never learned much from him. I spent three years in his classes and only spoke with him for a total of about 45 minutes.

Another of his students had no fear at all—he would go to this professor almost every day to ask questions. And he was criticized regularly, but he never seemed to care. I thought he was completely crazy, but he went back almost every day, got his questions answered, and learned a lot.

It took me several years after graduation to realize that I had wasted the opportunity of a lifetime—this other student wasn’t so crazy after all. He got many hours of personal tutoring from one of the world’s greatest mathematical minds, and I got through graduate school safely, without being criticized.

The Lord is pretty clear that He wants something more from us than this. He wants us to face our fears and do something good with the many talents and opportunities He has given us.

Consider His parable about the rich nobleman who entrusted his wealth with his servants while he went traveling abroad. You know the story, so I’ll skip to the end.

He which had received the one talent came and said, Lord . . . I was afraid, and went and hid thy talent in the earth. . . . His lord answered and said unto him, Thou wicked and slothful servant. . . . Take therefore the talent from him, and give it unto him which hath ten talents. . . . And cast ye the unprofitable servant into outer darkness. [Matt. 25:24–26, 28, 30]

This is a very severe punishment. After all, the servant took good care of that money. Not one cent was lost. Yet the master not only chastised him and took his talent, he cast him into outer darkness.

The Lord doesn’t care about not messing up. It isn’t enough to preserve what He has given us. He wants us to get up and do something with it.

Like the one-talent servant, when we fear failure we are more likely to fail.

When I was a teenager I worked for two summers as a lifeguard and a swim instructor, and I learned that people’s fear of water is usually their greatest obstacle to successful swimming.

A person learning to float on his back, for example, when he is afraid, will instinctively try to sit up, which causes him to sink. To float, he must relax and put his head back and his legs down. Then he can float on his back with very little effort.

The key is learning to trust that a little water splashing in your face does not mean you are drowning. It may not be what you imagine to be perfect floating, but it is good enough. Even going completely below the water is not failure—if you remain relaxed, a gentle hand motion quickly brings you back up to the top. But as soon as you become nervous, you try to sit up, and you sink.

Similarly, when my kids started ice-skating lessons, they were unable to stand on their skates without help and clung to the little walkers available at the arena for nonskaters. They were surprised when the first thing the instructor did was to take away the walkers and teach them to fall. They practiced falling over and over. One of my daughters complained that falling was the one thing she could do without lessons.

But once they had finished their falling lesson, almost as if by magic, they could skate. And they didn’t even fall much after that. By overcoming their fear of falling, they were able to try new things without fear.

The most important example of this is the plan of salvation. The entire plan depends upon our engaging in a very dangerous enterprise. Recall that Satan’s plan was to guarantee that bad things would not happen and that we would all return to our Father after our time on earth. This plan was rejected not only because Satan wanted all the glory for himself, but more important, because it would not work.

We cannot become like our Father in Heaven unless we learn for ourselves to refuse the evil and choose the good. We must act for ourselves and choose for ourselves. But, as Lehi tells us, we cannot do this unless we are enticed by two opposites—unless we have the option to fail (2 Ne. 2:11, 15). Not only must we have the option to fail—we will fail. We do fail. Often.

The most miraculous proof of God’s love for us is the Atonement of Jesus Christ. The purpose of the Atonement is precisely to allow us to recover from our many failures. He knows we will fail, despite our best efforts, and He has provided a way for us to be freed from our sins, to be healed, and to return to Him. We show our gratitude for the Atonement when we use it to overcome our fear of failure, trust in Him, and act on our best approximation.

When he was president of BYU, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland taught us that we hit what we aim at: “So, not failure but low aim would be the most severe indictment of a Latter-day Saint fortunate enough to be at BYU.” ⁶

I should have listened more carefully to President Holland before I went off to graduate school. I hit what I aimed at—I graduated successfully without criticism from my teachers. Technically, I did not fail. But, boy, did I aim low. Fear of embarrassment, fear of failure, fear of being considered dumb by someone I thought was smart—fear made me aim low. Don’t make that mistake. Aim high.

Please don’t misunderstand me. When I say “aim high” I do not mean aim to be successful in your career or to become rich or famous or powerful. Those might be things that happen along the way for a few of us. But if they are your target, you are aiming much too low. Section 121 in the Doctrine and Covenants tells us that if we aim at these things—if our hearts are set upon the things of this world and if we aspire to the honors of men—we may be called, but we will not be chosen (see verses 34–35).

When I say “aim high” I mean we must aim to develop our talents and use our opportunities the best we can to build His kingdom, bless His children, spread His gospel, care for the needy, heal the sick, discover truth, teach that truth, and bring ourselves and our families back to live with Him.

We will make errors along the way. Aim high anyway. “Not failure but low aim would be the most severe indictment.“

Some of the most powerful methods for solving hard mathematical problems are what we call iterative methods. You start with an approximate answer—sometimes just a random guess—but you use that guess to generate a new, slightly better answer. Then you take that new answer and apply the method again and again until you get as close as you need to the correct answer. In many settings iterative methods are both the fastest and most robust ways to solve problems.

Iteration is a powerful tool in our lives as well. We repeat these three steps over and over again.

Let me tell you about my son Spencer, who likes to run. His first official race, when he was 8 years old, was a 3K in Kiwanis Park. He did not do nearly as well as he had hoped. He really had to push hard to stay with the leaders, and, by the end, he just didn’t have the strength to keep up. He was a little disappointed. The next two days he was really sore. He was forced to admit he wasn’t as fit or as good at running yet as he wanted to be. But during that week he pushed himself harder in our daily run than he had in the past—he worked hard to prepare for his next attempt.

At the next race, one week later, he was a little worried he wouldn’t do well. But he got up and ran the race despite his fears. He still had to push hard to keep up, and he still didn’t stay with the leaders for the whole race, but he was able to stay with them for longer, and his time improved a lot. Some of that improvement was from working harder in our daily workout, and some of it was from really running hard in the previous race. He was still a little disappointed, though.

But he repeated the process. Admitting that he didn’t know as much about how to prepare for a race as he wanted to, he asked his uncle—an experienced distance runner—for advice on how to train better. Again he worked hard all week and felt nervous before his next race. But again he put his fear aside, ran hard, and did better than the week before.

All through that first season he repeated this process. With each race he improved his time—a lot. Each race motivated him to try harder in his daily runs and to learn more about running. The races themselves also helped make him stronger for his subsequent races. By the end of the season he had cut almost three minutes off his 3K time and had become one of the race leaders that others tried to keep up with.

Spencer was successful that running season because he followed the iterative method for pursuing perfection. Each week he admitted and accepted imperfection, he worked hard to improve, he braved his fears and made another attempt, and then he repeated the process over and over again.

This same process, this iterative method, will bring each of us closer and closer to perfection. We will not actually reach that goal in this life, but we will get better and better.

That’s How the Light Gets In

Let me conclude with the chorus of Leonard Cohen’s song “Anthem.” Cohen may not have meant this verse exactly the way I interpret it, but for me it captures very well the idea I am trying to express:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

Our bells are cracked. But let’s ring those bells that still can ring. Stop worrying about your failure to achieve perfection—perfection is not possible in this life. Instead embrace the light and healing power of Christ that come in through our cracks and imperfections. There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.

Tyler J. Jarvis, a professor in BYU’s Mathematics Department, gave this devotional address on July 9, 2013. Read the full text at speeches.byu.edu.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

Web: Follow BYU Speeches on Twitter (go to twitter.com/byuspeeches) to get live tweeting of devotionals most Tuesdays.

NOTES

- See Marcus Wohlsen, “The Astronomical Math Behind UPS’ New Tool to Deliver Packages Faster,” Wired, June 13, 2013.

- See “Julia Robinson: Functional Equations in Arithmetic,” Association for Women in Mathematics, 2005; awm-math.org/noetherbrochure/Robinson82.html.

- Jeffrey R. Holland, “Lord, I Believe,” Ensign, May 2013, p. 94.

- Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), vol. 8, p. 137.

- Elliot Butler, “Everybody Is Ignorant, Only on Different Subjects,” in BYU Studies, vol. 17, no. 3 (spring 1977); p. 282; emphasis in original.

- Holland, “A School in Zion”; quoted in Brent W. Webb, “Where There Is No Vision, the People Perish,” BYU Annual University Conference address, Aug. 23, 2011; https://speeches.byu .edu/?act=viewitem&id=1990.