By Charlene R. Winters, ‘73 Alumni Editor

By Charlene R. Winters, ‘73 Alumni Editor

BYU English graduate Mitchell A. Davis, ’82, worked in Hollywood for six years before beginning a more-than-10-year odyssey that culminated in December 2001 with the release of his own film. Called The Other Side of Heaven, the movie chronicles the missionary experiences of Elder John H. Groberg, a member of the First Quorum of the Seventy of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Based on Elder Groberg’s books about his Tongan mission, Davis’ film was an independent venture, an attempt to break from traditional Hollywood and tell the Latter-day Saint story. “Before leaving Los Angeles, I had worked for Disney Studios in its creative group as part of a team of executives who develop the screenplays that become movies,” Davis says. “I was privileged to have a small role in such films as The Rocketeer, Newsies, White Fang, and Dead Poets Society. Yet I was a tiny cog in a very big wheel and had very little to do with actual filmmaking. I was a studio suit, and when I later left Disney to work at Columbia, it was in a similar capacity.”

“Before leaving Los Angeles, I had worked for Disney Studios in its creative group as part of a team of executives who develop the screenplays that become movies,” Davis says. “I was privileged to have a small role in such films as The Rocketeer, Newsies, White Fang, and Dead Poets Society. Yet I was a tiny cog in a very big wheel and had very little to do with actual filmmaking. I was a studio suit, and when I later left Disney to work at Columbia, it was in a similar capacity.”

Davis says he began looking at the people who were succeeding in the movie business and realized that he did not want to be like any of them. “I developed a theory I call ‘survival of the unfittest.’ This means that the people who usually rose to the top were the people ready to stoop to the lowest levels, or who were willing to ‘eat their young,’ as they say in Hollywood.”

Also dissatisfied with his early film experiences was Richard A. Dutcher, ’88, of Mapleton, Utah. When he left BYU with a film degree, he thought he had learned the fundamentals of movie making. Five years later, after many stops and starts, he produced his first feature-length film, a romantic comedy called Girl Crazy. Dutcher completed the cable TV movie for a mere $55,000, an accomplishment that was possible only because he wrote, produced, directed, and starred in the film. With Girl Crazy, he learned how to take a film from conception through distribution, but he also became aware of something else.

With Girl Crazy, he learned how to take a film from conception through distribution, but he also became aware of something else.

“Right after my experience with that first film, I told myself I had spent too much of my life on something trivial,” he says. “I decided if I was going to be involved in an industry that is so risky, I wanted to do films I was proud of, regardless of whether they made money. I became so nauseated with the whole Hollywood system that I turned my back on it.”

The results of that decision are two films that clearly reflect his religious faith: God’s Army and Brigham City. A third movie, The Prophet: The Story of Joseph Smith, is projected for a spring 2003 release.

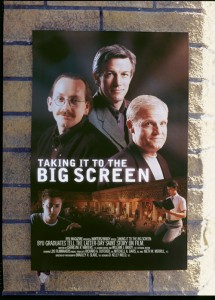

Davis and Dutcher are part of a number of BYU graduates who are emerging as filmmakers whose work directly reflects their religious roots. They are breaking new ground, producing the first major films by and about Latter-day Saints. And their creations are finding success and capturing attention. Dutcher’s films received critical acclaim and recouped their production costs many times over. God’s Army went on to play in 240 cities and gross $2.6 million, making it one of the top 50 independent films of the year. The Other Side of Heaven grossed more than half a million dollars in its first two weeks, and its opening-weekend per-screen average of $29,175 was 11th best in the nation in 2001. As other alumni follow Davis and Dutcher into the job market, they face similar challenges. They wonder whether to try mainstream Hollywood or become independent filmmakers. They ask how they can combine families and professions. They contemplate the messages they want to present and ponder how they can communicate their perspective and faith. Such were the issues addressed by James V. D’Arc, ’78, the curator of BYU‘s Arts and Communications Archives, when he spoke to a symposium of nascent LDS filmmakers in December 2001.

As other alumni follow Davis and Dutcher into the job market, they face similar challenges. They wonder whether to try mainstream Hollywood or become independent filmmakers. They ask how they can combine families and professions. They contemplate the messages they want to present and ponder how they can communicate their perspective and faith. Such were the issues addressed by James V. D’Arc, ’78, the curator of BYU‘s Arts and Communications Archives, when he spoke to a symposium of nascent LDS filmmakers in December 2001.

“There really are no easy answers,” he says. “I was impressed, though, that so many of them were concerned with combining their faith with their work; I don’t think this kind of symposium would have happened without the recent vision of LDS filmmakers.”

SEEKING IMPACT

Such a shift in vision is occurring with Kieth W. Merrill, ’67, of Cameron Park, Calif. Among other honors, the prominent LDS filmmaker received an Academy Award in 1973 for his feature documentary, The Great American Cowboy. He produced commercial films before turning to independent ventures, most recently documentaries for the giant-screen IMAX theaters. He also served as producer and director for the Church’s productions of Legacy and The Testaments, which he also wrote.

“During the making of The Testaments for the Church, I was struck with a real passion, a moment of inspiration, and a sense of focus to take advantage of the credibility, the confidence, and the access I have with the industry. I want to do something outrageous in the genre of religious film. I plan to make an epic film about Christ that will portray him as we understand him from latter-day scripture. This was President Hinckley’s instruction to me in preparing The Testaments. He said he wanted a Christ that all Christians will recognize and with whom they can identify.”

Merrill says that while he was in the process of shooting images for The Testaments, he realized LDS filmmakers have the capability to do faith-centered films on a much broader scale. For him the way to accomplish this is through Hollywood, an idea that differs from his earlier belief that Church members need to “keep to ourselves, raise $100 million, make these great films on our own, and then take them, hat in hand, to the industry.”

“I’ve had a complete switch in my perspective,” he explains. “Now I believe we can only do this within the mainstream. There is one major reason for the shift in paradigm. To have the maximum impact, the film must reach a worldwide audience. Utah and the Wasatch Front are not enough. My perception is that to access the mainstream market, you must have a mainstream product. That means having major distribution, bankable talent, and perception from within the industry that it’s a mainstream project.

“None of that precludes raising money independently and then going to the industry, but the reality is that there are currently about 2,000 independent films that have been made that way that have not been able to get mainstream distribution. It’s an issue of budget. You cannot independently raise enough money to produce a film with adequate A-list talent to compete in the major markets. If we’re ever going to have the kind of impact we need, we have to play in the big leagues.”

At the same time, he applauds the independent work of fellow LDS filmmakers.

“Richard Dutcher was the first one to step up and say the Church is now a market for film,” Merrill explains. “The Church has been a market for music and art, and now it’s big enough to be a market for film as well. Then, of course, Mitch Davis jumped into it with The Other Side of Heaven. He stepped up to the next level of ‘Let’s go out there with a real Hollywood-type movie and address a very specific LDS theme.'” Davis collaborated with some exceptionally skilled industry talents, such as Gerald R. Molen, a Church member and an Academy Award winner for Schindler’s List.

GIVING THE CHURCH A HUMAN FACE

Dutcher says being independent is a way to deliberately write from an LDS perspective. “I believe what should distinguish LDS filmmakers from others is our point of view. I see nothing wrong with the world knowing specific things about Mormonism.”

In Brigham City for example, he used a sacrament service in a symbolic way to show redemption and forgiveness, a choice that prompted both praise and criticism.

“I don’t court controversy, but sometimes I do a certain scene in a specific way to be true to my story and true to my goals,” he says.

“Dutcher uses Mormon theologies in a way that is very moving and accessible,” says Sharon Swenson, assistant professor of film at BYU. “As a student you could tell he was focused in terms of creativity, commitment, and ability. And it is nice that, regardless of whatever drives him, he doesn’t disregard the human touch.”

His champions also include national film critic Michael Medved, who wrote, “Brigham City features more vivid performances and richer, deeper emotional content than the noisy nonsense provided by most of today’s big-studio offerings. It also establishes Richard Dutcher, its 35-year-old writer, director, producer, and star, as a wunderkind of truly terrifying potential.”

Davis says he chose to leave Hollywood and create LDS films because he feared that if he stayed, he would eventually have a bigger voice, only to find that he had nothing to say. “I was concerned that I was forgetting who I was and what I wanted to be. I began to see that happening to me. I didn’t want to become part of the Hollywood machine and eventually lack the ability to make a difference.”

He moved his family to Colorado and wondered how he was going to use his religious faith in filmmaking. “The way I see it,” he says, “when Mormons are mentioned in Hollywood films, they consistently are portrayed as either backward hayseeds or prim and proper caricatures. For example, in the recent movie Contact, the religious lunatic who threatens to blow up Jody Foster’s rocket ship had to be a zealot from Panguitch, Utah. Provo was a joke in Ocean’s 11. By and large we are depicted as extreme rather than the regular people we are. The biggest problem is that we don’t have a human face, that we have failed to convey our humanity and our commonality with the rest of the human race. As long as we allow others to define who and how we are, those misperceptions will continue.” The impact of those misperceptions is vast given the global reach of Hollywood-produced motion pictures. Davis explains, “Never mind the theater. There are now so many ancillary distribution streams that disseminate Hollywood movies into every nook and cranny of the world. On average, a moderately successful, U.S.-produced film is seen by almost a billion people in its first two years of distribution once it is released on video and DVD, satellite and cable, and on TV. Make a movie that makes Mormons look bad and, two years later, almost a billion people across the world will have seen it. The good news is the opposite is also true if you make a movie that builds common ground between Mormons and the rest of humanity.”

The impact of those misperceptions is vast given the global reach of Hollywood-produced motion pictures. Davis explains, “Never mind the theater. There are now so many ancillary distribution streams that disseminate Hollywood movies into every nook and cranny of the world. On average, a moderately successful, U.S.-produced film is seen by almost a billion people in its first two years of distribution once it is released on video and DVD, satellite and cable, and on TV. Make a movie that makes Mormons look bad and, two years later, almost a billion people across the world will have seen it. The good news is the opposite is also true if you make a movie that builds common ground between Mormons and the rest of humanity.”

TELLING OUR STORY

Although making any film is demanding, Merrill believes specific challenges exist for filmmakers who are members of the Church. “I’ve been puzzling about that since I won the Academy Award,” he says. “There are challenges for any artist who believes in the gospel. Art by its very nature invites us to overstep boundaries and explore hidden worlds, to push our limitations, and to define society through the media we have. At one end of the extreme, you can say the gospel enables us because it defines us, and we can interpret the rest of the world through eternal truth. The other side of the equation is a sense of restraint, a sense of containment that I think is limiting. You struggle against it because you run into the wall of your own sensibility, placed there by your faith and your testimony. So you don’t explore some topics and some feelings and some sense of your creative discovery to the extent that you would or you could.”

He asserts that one of the primary objectives of being an LDS filmmaker should be to define priorities and live by them, something that requires courage in the difficult business of film. While Merrill adds that he recognized early on that a great movie is not all there is to life, Swenson suggests film is, nevertheless, a vital medium. “You can make a convincing argument that film has become the literary form of our time. It certainly is the basic and most pervasive medium to which children are introduced. When you add television and the Web to film, you have our most common forms of discourse. Despite this, some people think the best way to deal with film is to avoid it. While you and your family may choose not to see it, we live in a society where film influences everything from T-shirts to the games children play. If you turn the field completely over to people only concerned with celebrity, money, and the bottom line, you are abandoning your society. I applaud the Mormon filmmakers who are trying to make a difference.”

While Merrill adds that he recognized early on that a great movie is not all there is to life, Swenson suggests film is, nevertheless, a vital medium. “You can make a convincing argument that film has become the literary form of our time. It certainly is the basic and most pervasive medium to which children are introduced. When you add television and the Web to film, you have our most common forms of discourse. Despite this, some people think the best way to deal with film is to avoid it. While you and your family may choose not to see it, we live in a society where film influences everything from T-shirts to the games children play. If you turn the field completely over to people only concerned with celebrity, money, and the bottom line, you are abandoning your society. I applaud the Mormon filmmakers who are trying to make a difference.”

Dutcher says he believes the day is coming when LDS filmmakers will need to come together. “I hope we will have a community of moviemakers who support each other, because we have a powerful story to tell, and we need more than a handful to tell it.”

Merrill agrees. “I have often mused about who and what I’d be as an artist if I had never known anything about the Church, but my interest in knowing is overpowered by my gratitude for having been blessed by the gospel and the Church. I want to be totally supportive of any filmmaker in this Church who wants to tell our story in a positive way.”

web: For information about other recent LDS movies produced by BYU alumni, see magazine.byu.edu/extras.