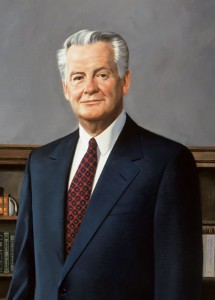

Of one heart and one mind in his vision for BYU and the kingdom, President Merrill J. Bateman never saw the two as separate.

It was an unusual first address for a freshly minted university president. Instead of laying out administrative objectives, enrollment goals, and curricula changes, Merrill J. Bateman began his presidency weaving together tales of missionary work, miracles, and building Zion. He was more than 550 words—5 minutes—into the January 1996 speech before the words Brigham Young University left his lips. But in reality, he had been talking about BYU all along.

It’s what people in the BYU community would come to expect over the next seven years. When their president, a General Authority in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, spoke of the “kingdom,” it was a sure bet that he also meant BYU. And in any mention of BYU, the kingdom was implied. The two were never separate in his mind. Nor were often dichotomous subjects like secular and spiritual learning and teaching and research.

“I didn’t see a division,” he says. “I have strong feelings that the university is not apart from but a part of the Church. It’s one of the arms of the Church used to bless its members and other people across the world.”

Seven years later, Bateman’s vision of BYU’s place in the kingdom has largely been adopted by the campus community. The gradual transformation came, in part, through regular reminders in devotionals and university conference addresses. From his first speech, “A Zion University,” to his final commencement address in April 2003, when he referenced Isaiah in describing BYU as part of the house of the Lord to which people go to be taught “of his ways” and to learn to “walk in his paths” (Isa. 2:3), Bateman has made the university’s place in the kingdom his constant refrain.

As President Bateman passes the reins to newly appointed Elder Cecil O. Samuelson, it’s that unified—and unifying—vision of BYU that Bateman’s colleagues say will be his legacy.

Bateman, however, downplays his contribution, arguing that he did not make any remarkable changes to the university and noting that his goals were similar to those of his predecessors. “BYU already was a great place. I haven’t done that much,” he says, insisting that he’ll quickly “go from who’s who on campus to ‘Who’s he?'”

Those who worked most closely with Bateman aren’t so reserved in commenting on the accomplishments of the university since January 1996 and on the man behind them. The university’s six vice presidents and other high-level administrators offer an inside perspective on the president and point to the unique set of virtues, educational background, business know-how, and Church leadership experience that intersect in Bateman. They say Bateman led BYU to unparalleled growth and a more unified vision of the role and destiny of the university.

K. Fred Skousen, ’65, vice president of advancement, puts it simply: “This time and season have been a perfect fit for a person of his abilities and vision for this institution.”

Watching Over His Flock

The cryptic message read: “President Bateman would like the President’s Council to gather in his office as soon as possible.” As the council members—vice presidents and assistants to the president—dropped everything and hustled to the president’s office, they couldn’t help wondering what had happened. Bateman had been attending meetings associated with the Church’s general conference. Had he learned of significant changes in Church leadership? Was there going to be a major shift in Church policy?

“We get in there and he just says, ‘The meetings were so wonderful. I want to share with you what I learned,'” recalls Janet S. Scharman, vice president of student life. “We were all laughing, but it was wonderful. He had enjoyed a powerful, spiritual, insightful experience. So what does he want to do? He wants the people he has stewardship for to have some of those same insights.”

In reality, this incident wasn’t too far afield for Bateman-led meetings, which regularly included impromptu discussions of gospel topics. “He’d just say, ‘I’ve been thinking about this. Do you have any insights?'” says Scharman. “I felt like we were at the feet of a wise, ordained leader of God bringing his flock along.”

In his leadership Bateman didn’t slip into the spiritual—the Spirit was integral to everything he did.

In the middle of one night early in his administration, Bateman says, he “woke up thinking about the need for a succinct set of statements that would really capture the essence of what we were and where we wanted to go.” Based on this experience Bateman and the campus community crafted four institutional objectives that clarified the university’s roles in teaching, researching, serving its outside constituencies, and making friends for the university and the Church.

Although Bateman had “four or five” such wake-up-in-the-night experiences, he says most of the spiritual direction he received was less dramatic. “You say your prayers and ask the Lord to help you. You pray for the faculty, staff, and students, that they’ll do their very best and rise to the occasion. Then you get up and go to work and do your very best. In the process, you see the Lord’s hand in it.”

Academic vice president Alan L. Wilkins, ’72, saw the Lord’s hand in Bateman’s leadership of a new-student-orientation assembly. The Marriott Center was brimming with school spirit—the marching band playing the fight song and students’ cheering reverberating across the hall. When it came time for President Bateman to share a spiritual message, he recognized that the tone wasn’t right. Without hesitation, he turned to Wilkins and asked him to lead the audience in singing “I Am a Child of God.” The atmosphere instantly softened, and the students became attuned to receive the message, which Bateman adapted, at the spur of the moment, to fit the song. “This was the Spirit magnifying his gifts,” Wilkins attests.

Bateman says he found strength in teaching the gospel. Despite his weighty administrative load, he continued to attend stake conferences as part of his General Authority duties. Far from a burden, the teaching opportunities invigorated Bateman. “Stake conferences were a time to revitalize my inner self,” he says. “The renewal comes from teaching the gospel to people.”

BYU—Hawaii president Eric B. Shumway, ’64, who reported directly to Bateman, admired his ability to merge his presidential and spiritual roles in his leadership. “He brought those two together nicely when he spoke. He was intellectual, quoting widely from great thinkers, but he stood as a witness of Christ, and that’s what I love about him.”

From devotionals to firesides at football-game bowl trips to team-taught Book of Mormon classes to off-the-cuff expressions of testimony, Bateman never passed up an opportunity to teach.

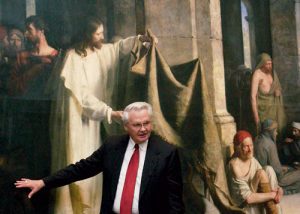

When the BYU Museum of Art acquired the Carl Bloch masterpiece Christ Healing the Sick at Bethesda, Bateman found opportunities to open the scriptures and teach various audiences of the symbols of healing and salvation painted into the mural. Jack Wheatley, who, with his wife, Mary Lois, donated funds to purchase the painting, says Bateman’s “depth of appreciation for the deeply spiritual message of this painting is without equal. In fact, one day I called him up and told him he was spending too much time at the museum,” he jokes.

J. Kelly Flanagan, ’88, chief information officer, witnessed the art of one such sermon before the painting and was moved by Bateman’s comments. “On a day-to-day basis, it was easy to forget President Bateman is a General Authority because we had such close association with him. But on occasions like that, you remember that he is, and you know why.”

Businessman Bateman

“This is going to make all the difference in the world,” Brad Farnsworth, administrative vice president, recalls President Bateman announcing to the President’s Council. BYU had the opportunity to buy satellite time to create BYUTV—a channel that would broadcast BYU to the world 24 hours a day. “Some of the other vice presidents and I didn’t quite see how this was really going to help,” Farnsworth admits. He says Bateman, however, was immediately able to envision how this would make devotionals, performing arts, and athletic events available to viewers from Pennsylvania to South America. Time would prove Bateman’s instincts correct. BYUTV is one of his longest-reaching successes, taking BYU and the Church to the world.

Bateman’s vision, business acumen, and leadership style became legendary among his colleagues. Farnsworth says that Bateman’s insight into BYUTV and other issues led to a saying among the vice presidents: “A lot of leaders have the vision to look down the road. President Bateman has the vision to look down the road and around the corner.”

Equally impressive to his colleagues was the pace at which Bateman evaluated information and made decisions. “Frankly, it was a little breathtaking sometimes,” says Wilkins, noting that the president’s associates were “often a little on their heels, especially early on.”

Skousen was impressed by Bateman’s direct approach to resolving issues. “He’s a very do-it-now kind of person,” says Skousen. “I’d raise some possibility, and he’d say, ‘Let’s check that out.’ And he’d pick up the phone and call. If we could get an answer right then, we got an answer right then, and we’d move on.”

Farnsworth remembers “swimming” at times in the torrent of projects they were managing. “Sometimes I’d say to President Bateman, ‘Boy, there sure are a lot of things going on’—meaning, ‘Are we trying to do too much?’ He would chuckle and say, ‘Yeah, there are’—meaning, ‘We’re not trying to do too much. Just stay the course.’ It’s confidence. It’s saying that everything will be okay.”

Much of Bateman’s success in confronting challenges, say insiders, came from his ability to work with a team. He readily delegated, openly accepted feedback, and didn’t micromanage others’ jobs. This mentality allowed the university to function more efficiently as he broke down traditional silos between units on campus and encouraged collaboration.

The businessman Bateman also left his stamp on BYU processes in other ways, such as developing a continual department-assessment program, rigorous resource planning, and a reliance upon hard data in decision making. Just as he had done as an investment analyst, Bateman depended on “metrics” to allocate campus resources and plan for future needs.

“President Bateman may be the best business mind I have ever worked with,” says Farnsworth. “He was able to implement business principles at a university while maintaining the academic environment we need to be a successful institution.”

Nothing if Not Avid

The officiating of the men’s basketball game had been “horrible,” remembers Q. Val Hale, ’81, men’s athletic director. At halftime a frustrated President Bateman summoned Hale. “Val, we’ve got to do something about this officiating.” He sent Hale to discuss the matter with the supervisor of officials, who was in attendance. After filing his complaint, Hale returned to President Bateman, who was sitting with Sister Bateman. But before Hale could report, Sister Bateman intervened:

“Val, don’t you pay any attention to him when he gets like that. He gets too emotional,” she insisted. “You just don’t pay any attention to him.”

“He just sat there with his arms folded,” Hale remembers with a laugh, adding, “He would get into the game—big time.”

With a sheepish chuckle, the typically decorous Bateman acknowledges that he can be “too avid” a fan.

Hale surmises that the common Marriott Center scene of Sister Bateman with her hand on President Bateman’s arm was primarily to help him maintain a presidential demeanor. Elaine Michaelis, ’60, women’s athletic director, adds that having seats next to Apostles probably didn’t hurt, either.

But Bateman, who played basketball and tennis in high school, had a lot to cheer about during his administration. From a Cotton Bowl victory on New Year’s Day 1997 to multiple national championships in women’s cross country and men’s volleyball to regular top-20 rankings in the Sears Directors’ Cup, these were banner years for Cougar sports. And Bateman was in attendance to witness much of it.

He was also actively involved behind the scenes. “People don’t realize how involved he’s been, in a good way,” says Hale. During his administration, Bateman had a part in helping BYU come into Title IX compliance, changing athletic colors and logos, and choosing new coaches in many sports. He was even complicit in smuggling D. Gary Crowton, ’83, into Utah incognito to interview him and arrange interviews with General Authorities during the highly publicized hiring process for the football head coach.

In early 1998, President Bateman led the counterattack when the NCAA eliminated its longstanding “BYU Rule,” which had required championship schedules to accommodate universities with Sunday no-play policies. Bateman rallied support for BYU’s cause, calling university presidents on the phone and writing a guest editorial for the NCAA News. An outpouring of support from universities across the United States caused the NCAA to reverse its decision.

President Bateman frequently expressed gratitude for the support of his wife, Marilyn, during his tenure. “When you have someone by your side who believes in you and cares about you,” he says, “it makes all the difference in the world.” Photo by Mark Philbrick.

Bateman’s fervent athletics advocacy stems in large part from his conviction that athletes can positively represent the university and the Church. “He believed that by winning with character we could open doors for missionaries around the world,” says Michaelis.

For Bateman, such interests extended beyond the playing field. He ardently supported and occasionally traveled the world with performing groups, encouraging them “to be a light to the world for what the Latter-day Saint people are.” He vividly recalls the impression the International Folk Dancers had on audiences during one tour through Eastern Europe. Audiences showed unusual interest in the BYU group, and he fielded many questions about what made these dancers different.

Bateman also rooted for BYU students and faculty and regularly praised them for their high academic and scholarly achievement. During his tenure the business and law schools steadily rose in their respective national rankings and BYU faculty and students have won national competitions, received substantial grants, and accumulated accolades in their various fields.

In making meaningful connections and friends for BYU and the Church, Bateman wasn’t content to watch from the sidelines. During his tenure he hosted some 90 high-ranking representatives from other countries. “President Bateman just charmed them,” says Sandra Rogers, ’74, international vice president. “He was very personable and well prepared on issues that were important to them.” Some visitors, wary of what they might find at a university sponsored by the Church, were quickly won over, she says. “The combination of a good student body, the fine faculty, and President Bateman’s engaging style pretty well convinced them that BYU is not a bad place. By the time they left in the afternoon, many were asking if their children could come to school here.”

The One and the 30,000

Following a banquet at the twilight of President Bateman’s administration, he took a moment to thank the student servers who had been involved with the meal. Farnsworth, who was leading the event, invited each student to say something to President and Sister Bateman. After several lighthearted remarks, one female student said, “We just hope President and Sister Bateman are as loved by the next people they lead as they have been here.” Visibly touched, Bateman stood and hugged each student.

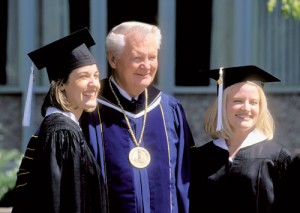

Scharman says Bateman was a “president for the students. They felt they had a relationship with him, which is pretty unusual for a university of this size.”

Along with formal question-and-answer sessions with students, that relationship was established through daily informal interactions on BYU sidewalks and across tables in the Wilkinson Student Center. Rogers recalls Bateman chatting with students about the previous weekend’s game and their ability to access the Internet. “Whenever I walked with President Bateman across campus to a meeting,” she says, “he was stopping to talk with students.”

President and Sister Bateman chat with a BYU Women’s Conference participant during a service project. President Bateman became known to the BYU community as a “people’s president” – one who was not only visible but also intimately acquainted with his constituency’s concerns and needs. Photo by Mark Philbrick.

Rogers saw the theme of the importance of individuals repeatedly surface in President Bateman’s devotional addresses. She cites an early talk on the individual and intimate nature of the Atonement, wherein Bateman expressed his belief that Christ knew each of those for whom He suffered. In another devotional Bateman considered the resurrected Lord’s invitation for the Nephites to approach Him, one by one. “President Bateman tried to follow that example in terms of his interest in individuals and helping them,” she says.

As for Bateman, he says he had additional reasons for the interaction. “Those 30,000 students kept Sister Bateman and me about 10 years younger,” he says. “They brought light and energy to us, and we loved it.”

Bateman attributes the connection he felt with students, faculty, and staff at BYU to his calling to serve them. “When you are called to an assignment in the Church, there is a special feeling of love and concern the Lord gives you for the people you are serving,” he maintains. “I felt it as a bishop. I felt it as a stake president. I felt it as BYU president.”

That bond made campus tragedies all the more wrenching for the Batemans. “One of the hardest things that happened to us was to have young people killed on the road,” says Bateman, recounting details of various student accidents over the years.

“He’d call me at home,” says Scharman, “and say, ‘Did you hear about this student that was in an accident? What can we do to help this family?’ He cares about the individual.”

Sister Bateman says they felt parental love for the students. “You don’t get to know much about each one of them,” she says. “But collectively, your hopes for them are just as great as they are for your own children.”

As doting campus parents, the Batemans can perhaps be forgiven if they had a tendency to brag about their 30,000 kids’ spiritual and intellectual accomplishments. And they were as concerned as any parents about the students’ moral, spiritual, and mental growth. “President Bateman didn’t mince words in devotionals about the Honor Code and students’ performance and choices,” Rogers says. “He understood the capacity we have here. He wanted students to recognize and take advantage of it. He wanted to put a support system in place that helps them to do that.”

Bateman hopes he’ll be remembered for that devotion, “that I really cared about the people and helped shape an institution that would allow young people to reach their potential.”

That students acknowledged and appreciated that devotion was evident in repeated standing ovations for President and Sister Bateman at a student assembly in the final days of his administration. “It’s hard to leave,” Bateman told the audience. “Our best friends are here.”

Celebrating BYU

What emerges from a review of President Bateman’s administration is his deep love for Brigham Young University and the church that sponsors it. This love is evident even in those things he wishes he could do again.

Bateman is candid in admitting that not everything went according to plans, especially early in his administration. “There were a number of events that kept me up at night,” he recalls, adding wryly, “I could hardly sleep.” He particularly worried about the way the university was represented in the media at times. “I had to learn how to work with the public and the media in a much more direct and open way than ever before. Anything we did got reviewed carefully by everyone. That’s something I’ve had to work through.”

Those who worked most closely with Bateman say this concern and his tireless efforts to improve and develop his abilities throughout his administration flowed from his deep affection for the university. “He desperately loves this university,” says Scharman. “His heart was here with the students. This was a continuous, 24-hour-a-day job for him. He was always thinking of things.”

No one witnessed that devotion more intimately than Sister Bateman. “He’s put everything—absolutely everything—into what he’s done. He worked all day long, and then when the evening came, we would have a group of people to entertain,” she says. “I asked him a few months ago, ‘What are we going to talk about when you leave BYU?’ because it was constantly on his mind. He put everything he had into it.”

For K. Newell Dayley, ’64, associate academic vice president, the Batemans’ passion for BYU was encapsulated in an image. For a few minutes early one morning, he observed President and Sister Bateman from an office in the Wilkinson Center. “They were walking the campus, and they were stopping and looking at this and that and pointing,” he recalls. “They were just celebrating this campus and what it stands for. I was struck with the realization that they really care. That was a hallmark of their administration—they really did care.”

Remaining Peculiar

In the weeks before Merrill J. Bateman became BYU president, President James E. Faust of the Church of Jesus Christ First Presidency, invited the announced but not inaugurated president to a BYU event where he would be speaking. “In his talk he mentioned that the spiritual dimension of religiously based universities is always under test,” Bateman recalls. After the speech, Bateman queried President Faust: Surely, he didn’t mean that BYU’s spiritual dimension was threatened. “Oh, it is,” President Faust replied. “You need to believe it.”

Bateman would soon become well acquainted with the challenges involved in preserving BYU’s spiritual roots. Early in his administration, when the university denied a professor continuing status for advocating principles contrary to doctrines of the Church, a widespread debate ensued over academic freedom.

“In 1992 the university had established an academic freedom policy that said we should provide broad freedom to individual faculty members, but within a context,” says Alan L. Wilkins, ’72, academic vice president. “There would be some limits—that we wouldn’t contradict Church doctrine, that we wouldn’t attack or deride Church leaders, and that we wouldn’t violate the Honor Code. During the Bateman administration those guidelines were just being tested. President Bateman and others made it clear that we will stand up for those principles.”

Receiving a donation of computer software and hardware worth $313.8 million in December 2002 added a thick layer of icing to the cake of BYU’s fund-raising efforts under President Bateman’s leadership. This donation and others improved facilities, bolstered technology, and made extensive student mentoring possible. Photo by Mark Philbrick.

In an effort to understand faculty concerns and clarify the university’s position on such issues, the president held regular brown-bag lunches with professors. “What we discovered is that faculty want this environment,” Wilkins says. “They feel more academic freedom here than they would elsewhere because they can talk about their religious beliefs.”

These findings from the lunches were backed up by a 1998 survey of BYU faculty by Baylor University researchers. They found that a vast majority of BYU faculty believe BYU’s mission is to “provide an atmosphere congenial to authentic spirituality” by encouraging spirituality and education (88.5 percent) and that most BYU faculty feel they have more freedom at BYU than they would elsewhere (88 percent) (see Keith J. Wilson, “By Study and Also by Faith: The Faculty at Brigham Young University Responds,” BYU Studies, vol. 38 [1999], no. 4, pp. 157–79).

Still, President Bateman remembered President Faust’s words and worked tirelessly to cultivate BYU’s roots as a peculiar institution. In fall 2001, he emphasized devotionals as an essential part of the BYU experience for students and faculty. Devotional attendance immediately doubled and remained high throughout his tenure. He also regularly expressed his belief that scholarship and devotion to the Church need not be at odds. “I honestly believe and believed from the beginning that a spiritual framework enhances the learning process—the classroom process and also the research.”

One opportunity to reaffirm the importance of spirituality in education came with the turnover of 600 faculty positions—nearly a third of all the faculty—during Bateman’s administration. He believed strongly that BYU could find Latter-day Saint candidates who were both well qualified and deeply devoted to the Church.

“The new faculty we have brought in over the past five or six years are just wonderful,” says K. Newell Dayley, ’64, associate academic vice president. “They are gifted, committed both to the Church and their discipline.”

Bateman believes two things are attracting such scholars to BYU: “One is the Spirit. The other is, from their statements, more freedom to speak about the things that are really important to them here than they would get elsewhere.”

BYU—Hawaii president Eric B. Shumway, ’64, believes President Bateman’s most important contribution to the university was his “affirmation and consolidation of the spiritual goals of BYU without compromise and without apology—his emphasis that the gospel of Jesus Christ and academics are not dichotomous.”

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

A Bigger, Better, Broader BYU

With the nearly constant presence of a crane and an excavation pit on campus during President Bateman’s tenure, it’s almost a sure thing he’ll be remembered for buildings erected on his watch. All told, he had part in some 43 building projects, including the library expansion, the renovations of the Wilkinson Student and Eyring Science Centers, and the groundbreakings of the Joseph F. Smith Building and new athletic buildings.

But Bateman’s aggressive building up of campus extended beyond structures to include infrastructure and programs. As former Presiding Bishop of the Church of Jesus Christ, he well knew of the widow’s mite and sought outside funding to make BYU bigger and better without drawing too heavily on Church resources. Thus he marshaled all available forces, and in 1999 BYU concluded its capital campaign early, having exceeded its $250 million goal by more than $150 million. And in following years, BYU regularly surpassed its fund-raising goals, despite a depressed economy.

One notable donation is the Ira and Mary Lou Fulton Supercomputing Center, where five supercomputers have faculty and students from some 22 BYU departments screaming along at more than 4 trillion instructions a second. The Fultons’ inspiration for this and other donations, says Ira, was Bateman’s leadership. “He’s always asking, ‘What can we do to make our students better, more marketable to the professions they’re getting into?’ President Bateman’s vision has always been the students.”

Before the final home game of the 2000 football season – the last for BYU coach R. LaVell Edwards, ’78 – President Bateman introduces Church of Jesus Christ President Gordon B. Hinckley, who would announce the renaiming of the stadium for Edwards and plans to build a long-anticipated practice facility. The moment is representative of President Bateman’s connecting role between the university and Church leadership. Photo by Mark Philbrick.

Because of BYU’s supercomputing capacity and technology prowess, in 2002 the university received a landmark donation of software and hardware valued at some $313.8 million dollars from PACE, a consortium of automotive and technology companies.

Substantial technological upgrades have also come to the classroom during Bateman’s tenure, and technology has increased BYU’s ability to extend its influence, a key Bateman objective that was formulated, in part, by an experience he had early in his administration.

A stake president friend in New Jersey had asked President Bateman to speak at a fireside, but on one condition—that he not talk about BYU. Surprised, Bateman insisted that if spoke, he would speak about BYU. The stake president explained that a large number of youth in the stake had not been able to get into BYU, resulting in many families developing bad feelings for the university. Bateman proposed that instead he discuss with the families how BYU might broaden its reach and meet their needs.

Such discussions planted the seeds for many outreach efforts, most of which flourished through improved technologies. Internet courses were added to BYU’s Independent Study program, and enrollment increased dramatically. BYU’s creation of a “digital library” made library resources available around the world. The summer open-enrollment program made it possible for non-BYU students to attend BYU during the summer months. And the creation of BYUTV has sent BYU devotionals, athletic events, and performances across airwaves and into homes everywhere.

These efforts to improve BYU as an institution and make it available around the world are aptly summed up in Bateman’s slogan World Class, Worldwide, says Sandra Rogers, ’74, international vice president. “He did a good job of blending the importance of connecting with the outside and having the horsepower to demonstrate the fine work we do as a university.”

Learning at the Foot of a Mentor

Economics grad student Merrill Bateman wasn’t expecting a perspective-altering experience during the class lecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). His teacher was explaining some of his research when his words suddenly cut short. “He didn’t say a word. He just had his eyes fixed. It went on for a minute,” Bateman recalls. “When it was finished, he just came back to the subject and went on.” A week later the professor brought to class a 40-page paper on the topic they had been discussing. The paper “opened up a whole new area of economics and general equilibrium theory,” Bateman says. “I’ll never forget it.” The teacher, who would become Bateman’s graduate advisor and shepherd Bateman through his own research activities, demonstrated to Bateman the power of integrating teaching and research.

When Bateman became BYU president, he inherited the long-standing debate of whether the university should primarily be an undergraduate teaching institution or a research institution. “There had been very strong statements about BYU being an undergraduate teaching institution,” he says. “But if you take that to the extreme, it could mean that faculty don’t do any research” and, consequently, miss out on opportunities to bring students along on explorations of the frontiers of their disciplines, as had Bateman’s MIT professor.

Bateman’s solution, building on earlier efforts, was to synthesize the two—in effect, to make BYU an undergraduate research institution. “I thought, Why not undergraduates? Why not legitimize research as part of the teaching process?” The widespread thrust that characterized the final years of Bateman’s administration became known as mentoring and had the goal of every student performing research with a faculty member and possibly even presenting and publishing the results.

To this end, the administration provided professors with significant funds to involve students in research through mentored relationships. The annual disbursement for mentoring grants increased from $300,000 to $10 million in just the third year, funding more than 4,000 mentoring relationships. Campus departments like electrical engineering revamped their curricula to better train undergraduates for the rigors of serious research.

“Mentoring is paying huge dividends for students,” says Alan L. Wilkins, ’72, academic vice president. He and other administrators point out examples, such as undergrads presenting at academic conferences alongside faculty and graduate students and a faculty member and a student coauthoring a cover article for Nature, a premier science journal. Bateman says this focus has allowed undergraduates “to operate at the level of graduate students at other universities” and catch the eyes of graduate-school and employment headhunters.

“President Bateman helped us formulate a vision that will allow us to be the best undergraduate university in the country in terms of producing significant research and students who are well trained,” says K. Fred Skousen, ’65, vice president of advancement. “You don’t hear faculty in the halls talking much now about whether we are a teaching institution or a research institution. We’re both.”