In a new exhibition at BYU's Museum of Art, visitors catch a glimpse of ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, three societies that formed the foundations of Western culture.

After his death nearly 2,800 years ago, the body of young Egyptian priest Pennu underwent a 70-day mummification process and an amulet was inserted between his teeth for good luck. Like other Egyptians, he believed preservation of his body would guarantee his passage into the eternities.

It is likely that Pennu, also called Opener of the Doors of Heaven, believed he would travel to a blessed afterlife in some far-off place. It was impossible, however, for him to imagine that nearly three millennia later his mummy and coffins would be transported to a place called Utah for exhibition at BYU’s Museum of Art.

The priest’s remains are among 204 artifacts assembled for the Art of the Ancient Mediterranean World, a glimpse into a world where Egypt, and later Greece and Rome, provided the foundation for Western culture. Through June 4, 2005, museum-goers can discover abundant tales and textures of antiquity captured in stone, wood, glass, gold, and ceramics. The exhibition comes from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Life Preserved

A narrow and shadowy threshold opens the exhibition and introduces patrons to prized objects from Egypt dating back as far as 6,000 years. The artifacts, most of them discovered in tombs, illustrate Egyptians’ elaborate preparations for the afterlife.

Pennu, for example, rests in a darkened “tomb room” gallery, surrounded by artifacts considered necessary for another life. Among them are a ba bird, canopic jars, and several shabtis. The ba statuette, a bird with a human head, was more than a reflection of the dead person. It was considered, in effect, to be the ghost of the deceased. Egyptians thought the ba could exit the tomb and enter the realm of the living during the day, returning at night to restore and reanimate the mummy. Canopic jars held the lungs, liver, stomach, and intestines of a mummy. The heart was kept inside the mummy for later judging by the gods; the brain was discarded. In the first and second Egyptian dynasties, servants were killed and placed in the tombs of their masters. Later, statuettes called shabtis took the place of human servants. Their purpose was to work as representatives of the deceased should he or she be called by the god Osiris to labor in the fields of the afterlife.

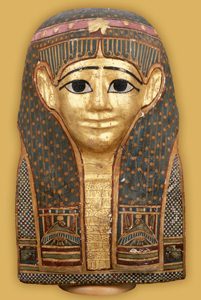

Inner Caronage Coffin of Pennu, Egyptian, 800-720 B.C. Made of Linen and plaster, the inner coffin of Pennu still contains the young priest’s remains.

The tomb room’s centerpieces are Pennu’s two coffins; the outer coffin has been opened to reveal the inner coffin, which remains closed. X-rays reveal that the inner coffin still contains the priest’s remains, as well as the amulet, but massive deterioration over time has made the mummy extremely fragile. The inner coffin itself, made from linen and plaster, is in much better condition. Protective goddesses and other figures are painted on the coffin to assist Pennu in his long journey. His outer coffin is made of wooden planks, with the face made separately in a fine, dark wood.

The remarkable stability and refinement that characterized Egypt prompted a desire in Egyptians to perpetuate their good life into the eternities. Egypt became a funerary society, says Rita Riddle Wright, ’76, museum educator, not because its citizens desired death but because they wanted to continue their lives beyond the grave. Tomb artifacts, such as those of Pennu, have given the world much of its information about daily Egyptian life.

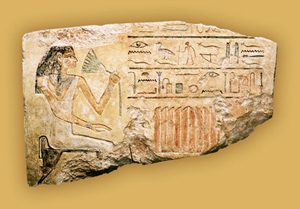

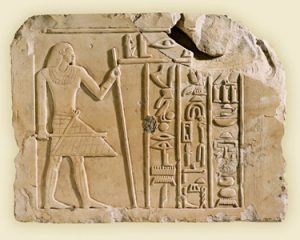

Through elements placed in another tomb, BYU patrons glimpse the life of Nekhebu, a simple builder who rose to become the royal architect during the Sixth Dynasty (2390–2361 b.c.) under the reign of King Pepy I. Nekhebu’s tomb, heavily damaged after Romans built an asphalt road over it, still contains much of the story of his life. Six matching relief panels show that he had priestly duties as well as secular ones, his scepter and staff are indications of high authority, and inscriptions found in the tomb describe his role as a builder of temples, tombs, and elaborate irrigation systems. The inscriptions also describe generous gifts of bread, beer, and gold from the kings.

The artifacts tell much about how Nekhebu saw himself, and, as museum designer Paul L. Anderson explains, “from his autobiographical writings, we learn about him and his family. Nekhebu defended himself as a good person in the eyes of the gods who would judge him in the afterlife. He explained his moral attitudes by writing that he did not beat or enslave his servants and that he was respectful to his parents.”

Dekadrachms, Greek, 413-387 B.C. These coins depict a charioteer and goddess Victory (Nike) on one side, and the head of Arethusa, a nymph on the other.

Persistent Influences

As the exhibition transitions from Egypt to Greece and Rome, it becomes apparent that artistic traditions of the Egyptians influenced the later civilizations, especially in the strong vertical lines of the figures and the basic sense of how the body is hinged together. Additionally, the idea of art on a monumental scale was introduced in Egypt.

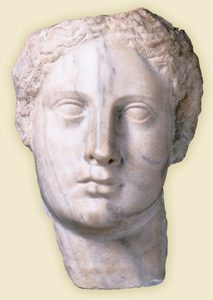

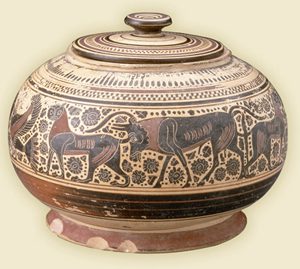

“In the archaic period of Greece, as well as in some of the other advancing Mediterranean cultures, you see the sideways perspective of the Egyptians,” says Cheryll Lynn May, ’64, museum educator of public and volunteer programs. “You see that figures are represented in profile as they are in Egyptian paintings. Only in the really high classical period in the Greek golden age do you have the artists striking out to gather the courage and skill to represent human and animal figures frontally.” A wild goat pitcher from the Greek orientalizing period (625–600 b.c.) depicts stationary, walking, and leaping goats in profile, and a lidded jar from the Greek archaic period (600–575 b.c.) shows animals in procession in the Egyptian style.

Red-figure lekythos, Greek, ca. 470 B.C. This lekythos, or perfumed oil flask, demonstrates the simple yet sophisticated composition of the Greek early classical period.

Greek artists’ style was originally as stiff and rigid as that of their Egyptian mentors. With a keen interest in human figures, however, the Greeks began to create figures that appeared natural, alive, idealized, and intelligent.

“The Greeks expanded Egyptian philosophies and emerged with a classical ideal,” Wright says. “They began to look at nature and the characteristics in the natural world they found particularly pleasing. We see the golden mean of proportion evident in the works shown at BYU. We see their stories, especially in the wonderful collection of Greek vases.”

The vase gallery is a breathtaking room filled with pristine examples of both red- and black-figure containers. Dramatic lighting illuminates the vases in the darkened room, revealing stories of Greek legend and belief. One can almost sense the ferocity of the battle, for instance, on a black-figure water vessel that shows Hercules wrestling with the sea monster Triton. Also among the vase treasures is an imposing mixing bowl featuring Medea extracting deadly revenge on a king who had usurped the kingdom of her husband, Jason.

“Despite the beauty they sought,” May says, “the Greeks were politically fragmented and could not keep chaos at bay. The Greek golden age lasted a mere 100 years before disorder overcame the glory that was classical Greece. Unfortunately, they themselves were never able to accomplish the kind of harmonious society in which they so believed.

“The Romans facilitated the spread of Greek civilization throughout the Mediterranean and European worlds because of their hundreds of years of stability and basic peace and prosperity,” May adds. “They conveyed many of the breakthroughs and cultural forms developed by the Greeks and had their own innovations, including engineering in roads and aqueducts, and they did much more with arches than the Greeks ever did.”

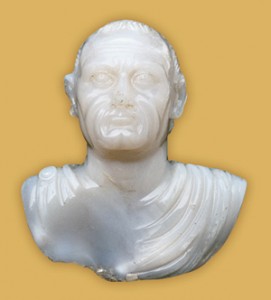

In the Roman Forum that takes up the final gallery, it becomes evident that as the Roman Empire continued, more Romans decided they would rather be portrayed as they really looked than be idealized. A miniature statue of Emperor Vespasian, recut from a bust of Nero, for instance, shows a balding, wrinkled man rather than an idealized military figure. A roundel—or wall plaque—of a middle-aged couple shows their mutual devotion through thoughtfulness in their eyes. This culture stressed the dynamism of human expression in sculpture.

The legacy of these cultures is abundant. One need look only at the pyramid on a dollar bill, the obelisk-shaped Washington Monument, and the art deco Empire State Building to see influences of Egypt. The historic Provo Courthouse and BYU’s Maeser Building are influenced by Greek temple architecture, and the Utah Capitol is very Roman.

“This exhibition allows us to speak about a part of our own history and allows an examination further back in time than we have ever had here before,” says Campbell B. Gray, museum director. “It gives us a wonderful moment to talk about the origination of philosophical thought, mathematics, political and social structure, and the nature of humanities and architecture.”

“In many ways,” Anderson adds, “we have never had any better ideas about art and the dignity of learning than did these ancient people.”

Info: Hours, admission pricing, and other information is available online at byu.edu/moa or by calling 801-422-8287.

The Museum of Art Web site (byu.edu/moa) features an educational interactive program with photographs of and information about every artifact in the Art of the Ancient Mediterranean exhibition.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.