When President Rex E. Lee started asking why it was taking students an average of six years to earn a four-year degree, he quickly learned that the university needed to change its system.

by Carri P. Jenkins

Photography by John Snyder

It used to be, come graduation time at BYU, that you could get a pretty good slap on the back for making it through in less than a decade. But this feat just doesn’t measure up anymore. If you really want to hear accolades today, try trumpeting this announcement: “I’m graduating from BYU in four years.”

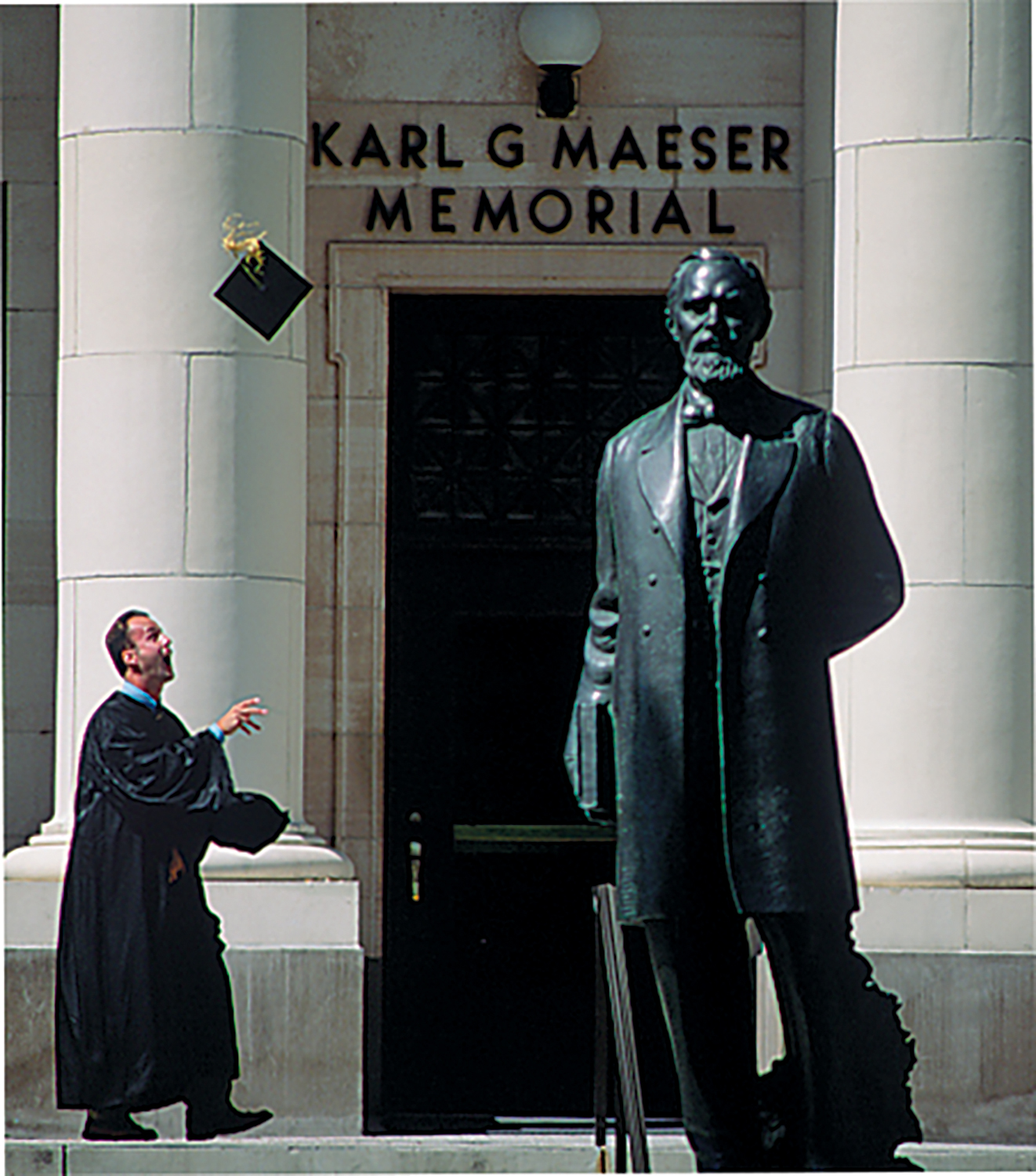

Ooh, just look at those fireworks going off behind the Smoot Administration Building. And is that really President Rex E. Lee doing cartwheels in his office?

“What is going on here?” you ask. “Since when did it become such a big deal to graduate in four years from a four-year college?”

A silly question for someone who has been on campus the last four years, but, okay, a legitimate one for an alum. And since you ask, let’s start at the beginning.

As President Lee tells it, it all began in 1991 during one of his weekly meetings with the provost and academic vice president. At this particular meeting, the academic vice president was presenting the most recent enrollment figures, which were not good—mainly because BYU was about 2,000 students over its cap of 27,000.

But how, they asked, could this be happening? After all, the university had just seen one of its largest classes graduate, and everyone in the room had experienced the agony of turning away an increasing number of well-qualified applicants who had planned all their lives to attend BYU. In essence, the numbers coming in and going out were right on track, so why the burgeoning enrollment figures?

It didn’t take the administration long to figure out the problem: BYU students were taking an average of six years instead of four to graduate, creating a huge pileup in the middle.

The figures also implied that if BYU could reduce the average time required for graduation from 12 to eight semesters—from six years to four—it could at the same time increase by 50 percent the number of students admitted each year, and still stay within the 27,000 enrollment cap.

Some may tell you that upon hearing this, President Lee immediately climbed the stairs of the Carillon Tower and started shouting at the top of his lungs, “Get out, you lazy laggards. Your time is up.”

But nothing could be further from the truth. Although, admittedly, the president has taken his concerns to both the students and faculty, he has never dumped this burden at the students’ feet.

From that first meeting, the focus has always been to look at what the university could do—in admissions, advisement, major requirements, transfer policies, and general education—to more efficiently help guide students toward their goal of graduation.

“We realized that the university had not done a good enough job in helping students establish a plan for graduation,” President Lee says. “In the fall of 1993, we had 49 seniors who had still not declared a major, 1,451 students with over 150 hours, and 670 seniors on academic probation. And although these students had ample credits to graduate, many were no closer to reaching that goal than some of our freshmen. Something had to be done.”

The System and the Students: A Dual Approach

John Tanner, associate academic vice president and in President Lee’s words “the real hero of this story,” was asked to spearhead what might be called “Operation Four.” His mission: to pinpoint why students weren’t graduating in four years and then do what was necessary to decrease the time-to-graduation, all while maintaining the quality of a BYU education.

In addition, Tanner was determined to improve BYU’s graduation rate. “Too many students,” he says, “were not graduating at all—in any amount of time.”

Fortunately, others shared these same concerns, including Gary L. Kramer, associate dean of Admissions and Records, and Bruce Higley, director of Institutional Studies, who conducted preliminary research that resulted in several of the graduation initiatives

in place today.

As Tanner became immersed in the arduous task of turning over the university’s stones and examining what lay underneath, President Lee was rallying the troops. In meeting after meeting, he pled with students to work toward a timely graduation. He was not, he emphasizes, asking students to race through in two or three years but simply in the once-upon-a-time accepted four years.

Some students, of course, were alarmed, particularly those “major-less” seniors who were not allowed to register until they visited an advisement center. Several, according to Director of Academic Advisement Raylene Hadley, were just enjoying school too much, like the young woman who had spent nine years total at Ricks and BYU and was pursuing her fifth major. As a member of one of the university’s

performing groups, she simply was having too much fun. Some didn’t want to leave BYU Housing or pull out of student jobs. And still others were running lucrative businesses as students and didn’t want to give up the resources at their disposal. But most found themselves caught in a maze and desperately wanted to find a way out.

Whether they agreed with the president or not, the students caught his message. And in the process, a peculiar phenomenon began to happen. Although, under Tanner’s leadership, the pursuit of timely graduation was becoming an institutional endeavor, the students identified the cause almost solely with President Lee.

In fact, faculty say that many students have diligently pursued a plan of graduation in order not to disappoint their president.

“I don’t know why this has become my initiative,” says President Lee. “But I think it is something that has happened. I remember one student—and he was one of many to do something like this—wrote a postscript to a scholarship application for spring/summer terms that said, ‘Rex, no thanks—I’m graduating. I made it in four years!’ ”

And President Lee did a cartwheel just for him—well, figuratively speaking.

Program Planning: Student Advisement Becomes a Priority

As President Lee stresses, however, this effort is a university-wide operation that has involved thousands upon thousands of hours from every division on campus. “For especially the 10 colleges, this has been a painful endeavor as they have had to make cuts in their programs. But it has been very gratifying to see the cooperation that has existed.”

For Tanner, this cooperation among the faculty, deans, administration, advisement counselors, and students has been and still is crucial to achieving success. His work has revealed some interesting insights into why students were taking so long to graduate.

Obviously, some responsibility for delay could be placed on the students themselves, a few of whom had made little effort to graduate in any amount of time. But BYU also needed to do more to help students graduate. In some cases, the university made it unnecessarily difficult for students to make it through in four years.

In light of such news, President Lee asked every department with a major requiring more than 60 hours to cut back. If they could not do this—if certification or licensing absolutely prevented it—then they were asked to be honest and up-front with students about how long it would take to complete the major.

In the meantime, Hadley and her team at Academic Advisement were identifying students at risk and developing better methods to help them progress through the university in a timely manner.

Starting in the fall of 1993, all seniors without majors, students with more than 150 hours, and seniors on academic probation were placed on registration hold—meaning they had to visit an advisement center before they could register. Such students, however, were informed about the hold through a letter long before their registration was due.

“Nonetheless, we had a lot of disgruntled students that first semester,” remembers Hadley, who counseled many of them, “because there is no really nice way to tell students that they must come in for mandatory advisement. But what we really wanted to do was to help them focus and be directed toward something they enjoyed. The problem is no one had ever stopped most of these students and said, ‘Let’s talk about this major. What do you want to do when you graduate? Is this something you will like doing?’ ”

Today’s freshmen and sophomores are now asked similar questions by the advisement counselors in every department—for instance, if they love literature and hate math, why are they majoring in civil engineering?

“This is a little new for many of our counselors, and they are definitely being asked to spend more time with students,” says Hadley. “Consequently, many of our departments have needed to hire new advisement counselors. But there is no disagreement that this is the direction we need to be heading. In fact, winter semester of ’94 the Microbiology Department asked us to put a registration hold on every single one of its students that could not be lifted until they met with their faculty advisor to establish a plan of graduation. This program was so successful that the College of Biology and Agriculture adopted the same program last winter for every one of its students. And instead of hearing grumblings from the students, all we heard was, ‘Why didn’t you do this sooner?’ ”

For President Lee, such early intervention lies at the heart of timely graduation. “We are throwing around a four-letter word here,” he jokes, “and it does start with a p. But it’s not push, it’s plan. And helping the students do this is one of our top priorities.”

There are two reasons this must be done, he says. The first, as already mentioned, “is to benefit those worthy, qualified young people who desire to be admitted to BYU, but have not been and will not be unless we can reduce our average graduation time.

“But there is also the benefit to our students who have been admitted who are less well served if we keep them here longer than four years,” President Lee says. “To whatever extent we extend their years at BYU beyond the four we believe to be really necessary, we deprive them of time they could and should devote to their lifelong living circumstances—settling into a home with their families, establishing themselves in their lifetime’s work, and earning an income.”

Pruning, Trimming, and Reexamining: The Program Overhaul

Yet President Lee is not alone in recognizing that if a program requires high hours—or if its courses are so time-intensive that students are limited in how many they can take per semester—there is no amount of planning a student can do to make it through in four years.

“This is why the burden has rested so heavily on our colleges and departments to review their requirements,” says Tanner. “Essentially we have asked that departments scrutinize every degree and prune where possible. Trimming the curriculum is a productive exercise, but painful.”

In the end, there has been a reduction in the length of majors over the past three years by an average of 6.6 credit hours. “This is impressive,” says Tanner, “though the task is not done. Many majors are still above the university guideline. Hence, further review of the curriculum will occur this year as part of the university’s self-study.”

For some majors, such as those in engineering, nursing, and the fine arts, the reductions have been felt deeply. “Our technical requirements have been reduced to the bare bones,” says Joseph C. Free, an associate dean in the College of Engineering and Technology. “At 128 hours (including G.E.), we have reduced our program as much as possible to remain competitive with other schools. We are certainly in support of President Lee, but if anything further has to go, it has got to be the general education requirements.”

Tanner anticipated that many faculty members might feel this way. And so, to be fair, he asked General Education to review its program with the same objective: to ensure a strong but more streamlined program. In fact, the Faculty General Education Council under the direction of Edward A. Geary, an associate dean in the College of Humanities, spent 18 months reviewing and revising BYU’s G.E. program. In April, Tanner announced that a “stronger, streamlined” general education program had been devised.

The revised G.E. requirements eliminate several bottlenecks found in the old program, modify the health/physical education requirement, and reduce the elective requirement by one course, thereby decreasing total student loads by 3.5 credit hours. (See related article on page 29.) “Even more important,” says Tanner, “the revised program greatly simplifies G.E.”

“The change I am most delighted with,” says General and Honors Education Dean Paul A. Cox, “is the universality of the new program. In the past, there were 13 different general education programs that varied according to the student’s major. The new G.E. program is the same for all BYU students, regardless of major.”

Council members describe the new system as “student friendly”—a phrase that seems to roll off the tongue of everyone involved in the graduation endeavor. “I suppose you could say,” says Cox, “that we’re all working to produce a simple rapid transit system to make the university more friendly to our students and also accessible to a greater number of students. We all understand how important clarity is in terms of students planning their educations. It is absolutely necessary.”

A Kinder, Gentler School: Making the Little Things Easier

Perhaps no one is more grateful for this “clarity” than BYU’s transfer students. For the past several years, major improvements have been made in this area.

BYU has now signed six Transfer Consortium Agreements with its principal transfer schools, and it is working closely with transfer students from other accredited colleges. The agreement means that an associate of arts or sciences degree at any of these colleges now automatically fills most of the BYU general education requirements. The only courses not filled are advanced writing, advanced math or foreign language, and religion classes.

Under the “student-friendly” category, the university has also announced significant tuition reductions for the spring and summer terms (27 percent lower this spring/summer than the past spring/summer). “We really are offering every single one of our students a scholarship for these terms,” says President Lee, who hopes the students will take advantage of this time, particularly since all of the departments have added greatly to the courses available during the summer.

It has become an accepted fact that students who do not have to earn money for tuition and living expenses while attending school graduate faster and do better academically, President Lee adds. One of the fundamental goals in BYU’s soon-to-be-announced capital campaign is to increase the availability of financial aid to qualified students.

Another is to improve the overall quality of student education by reducing student-faculty ratios and adding more teachers in key areas.

The new university catalog, which has been touted as, once again, “student or user-friendly” and has undergone significant revisions, is one more sign of progress. Released in April, the catalog clearly displays all requirements for every major, course availability information, a suggested sequence of courses over a four-year period, a summary of degree requirements, and the minimum number of semesters needed to complete those requirements.

It’s a catalog that every alum can appreciate.

In all that has happened since 1991, about the only step taken toward timely graduation that might not be considered “student-friendly” is the one announced this spring. Scheduled to become effective in fall semester 1998, the plan calls for gradually increasing tuition for students who stay at the university longer than 10 semesters, or five years. The change affects only students enrolled full time and counts only fall and winter semesters.

“The program signals that students don’t have an unlimited claim on the Church subsidy of their tuition,” says Tanner. (The LDS Church pays approximately 70 percent of the cost of educating an LDS BYU student.)

In their 11th semester, students will pay 25 percent more than normal tuition. In their 12th, the charge will be 50 percent higher, and so on. The surcharge will be capped at 100 percent.

“I expect that the program will result in few students being charged a penalty, but our hope is that many students will be doing better planning,” adds Tanner.

The university will provide transfer students with a pro-rated number of fully subsidized semesters based on the amount of transferable credit. In addition, it has established an Exceptions Committee that will hear appeals from students with unusual personal circumstances. “And we will apply these waivers liberally,” President Lee adds.

“Over the past two years I have probably met with two dozen groups of students and raised this issue of a tuition surcharge with them,” says President Lee, “and I have been pleased to find that most of them felt it was a fair provision, so long as the university takes steps to make graduation possible in 10 semesters.”

Program Pressure: Being Sensitive to Student Stress

James D. MacArthur, a psychologist at the Counseling and Development Center, shares the students’ concerns. Too often, he says, all that the students hear is “hurry, hurry, hurry,” which adds to the stress they are already feeling as college students. “For this reason, it is important the students believe the university is doing all it can do to help.

“The students coming in today are more sophisticated; they are brighter and better prepared than they used to be,” says MacArthur, who has been at the university for 22 years. “So when you tell these kids to ‘hurry,’ it creates a stress dynamic that is pretty scary.”

MacArthur also points out that BYU students go through far more transitions, labeled as stress points in a person’s life, than other college students. For instance, 85 percent of the male students leave for missions following their first year. Female students who choose to serve missions usually leave following their third year. These exits and entrances can be filled with tension.

In addition, compared to typical college students, more BYU students marry and have children while in school. “Many of our students experience half a dozen crucial transition points, all while in school,” explains MacArthur. “Many of them must also work to finance their educations. And although I completely support the university’s efforts to move students through—simply because my kids and your kids and others’ kids are standing in line to get in—we must do all that we can to help our students.

“As long as there are people out there to listen to and support our students, then I don’t fear the streamlining. But we can’t expect our students to make it alone. We have got to say to the point of nausea, ‘We care, we care, we care. And this is what we are doing to help you.’ ”

Although he has never used the term “hurry,” President Lee is well aware that this is a definition some students have assigned to his message. He also fears that a few students, in their rush to finish, may simply select any major. And he has heard concerns that if students feel too pushed, they may forfeit such extracurricular activities as intramural sports, drama, and student government.

“Our intent has never been to exclude these types of activities,” says President Lee. “Furthermore, we understand that college is a place where many students come to find out what they want to do with their lives. This is why the new G.E. program, which is the same for every major, is such a bonus for students—they don’t have to come here knowing what they want to do.”

On the other hand, Chris Covey, a senior in public relations, came to BYU as a transfer student thinking he knew exactly what he wanted to do: become a dentist. While at Utah Valley State College he had visited BYU often to make sure he was taking the correct G.E. classes. Once enrolled at BYU, he planned his schedule carefully, following all the outlined suggestions. He seemed to be doing everything right.

But his first semester at BYU was horrible. He quickly learned that he didn’t enjoy his science classes and that dentistry was the last field he wanted to work in. Realizing he had made the wrong choice, he cornered an advisement counselor in the Communications Department and asked for help.

“She gave me the direction I needed and really helped facilitate my decision,” says Covey. “But because of that semester, I will not graduate in four years like President Lee has asked of us. I have gone spring and summer terms, however, and will finish my degree by December.

“But my wife, Katherine, now she is going to make it in four years—and that includes her student teaching.”

Streamlined but Adaptable: No Cookie Cutters Here

So, is President Lee proud of Katherine and disappointed in Chris?

“I am not disappointed in him at all,” says President Lee. “Students do change their majors. I changed mine. Our students must be allowed this freedom. And, as Chris found, this is why we have improved our advisement centers—to help students make these choices early on and to get on with what they really want to study.

“This program has got to be flexible enough to take more than a cookie-cutter approach to educating our students,” says President Lee. “We want this to be a superb experience that gives students a foundation on which they can appreciate all aspects of life. We want our students to learn how to write with power, precision, and persuasion. We want them to understand mathematics, and we want them to study the Book of Mormon and other modern scripture as well as the Old and New Testaments. At the same time, we want them to learn how to make a good living. In essence, we want them to leave here with the adaptability and durability to face whatever the future may hold for them. And we truly believe that in most cases, with proper planning on our part and theirs and with cooperation all around, this can all be done in four years.”

Getting the Most Out of General Ed

Even taking into account all his studies abroad and his courses at Harvard, Paul A. Cox, an internationally known botanist, still counts the humanities class he took at BYU as one of his most valuable.

“Todd Britsch, who taught the class and who is now our academic vice president, taught me to see the world in a different light,” says Cox, dean of BYU’s General and Honors Education. “I travel quite a bit in my work, and everywhere I go I search for the art museums. Because of his class, I can look at the paintings and sculptures and understand their contexts. It was just one class, but it has paid great dividends and enriched my life considerably.”

For Cox, such opportunities are a precious treasure every BYU student can enjoy. “BYU is more than just preparing students for professions,” he says. “It’s teaching them how to live a life and live it richly.”

With such strong feelings, Cox admits it was difficult two years ago to ask the Faculty General Education Council to reevaluate BYU’s G.E. program in light of President Lee’s mandate to improve the university’s graduation time.

“Dean Cox and John S. Tanner [associate academic vice president] gave us the express challenge to strengthen and streamline the G.E. program,” says Edward A. Geary, the council chair and an associate dean in the College of Humanities. “But beyond this charge, we were given no other guidelines. Everything was on the table.”

To begin with, the council, made up of representatives from each college, began an extensive study of G.E. programs at other top-ranked universities. What they found was that BYU is “right in line” with these other schools.

They also found that the total hours required for general education and those allotted to majors is very comparable. Where there is a difference, however, is in the number of free electives BYU students can take, compared to programs elsewhere.

“The reason for this is the 14 hours of religion BYU requires,” explains Geary. “For some this may seem to be a penalty, but for others it represents the benefit of going to the Y. This is what a BYU education is: You get the same level of rigor in a major, the same enrichment in general education, and additional study in religion.”

Reducing the religion requirement was never considered, says E. Dale LeBaron, council member and associate professor of church history and doctrine. “This is because our board of trustees has set this requirement, and we were not asked by them to change it.”

LeBaron doubts anyone on the committee would have suggested such a proposal anyway. “Sitting on this council really showed me just how serious the administration and faculty are about religious education at BYU. There was and is a general feeling that religion courses are not just incidental aspects of a student’s experience here, but rather the very heart of it.”

After agreeing that the structure of BYU’s G.E. program should not be changed, the council sat down to the arduous task of streamlining the program. The council also took into account advice and research from the General Education Student Advisory Council and from numerous deans and faculty members on campus.

“Realizing that there were no grounds for radical change, the spirit of our work really became one of streamlining,” explains Geary. “At first glance, our changes do not appear very sweeping, but the new program allows for far more flexibility and deletes many of the roadblocks that students had been stumbling over.”

For instance, the new program is considered universal or “major-blind.” In the past, there were 13 different general education programs that varied according to the student’s major. The new G.E. program is the same for all BYU students. Hence, if students change their majors, they will not be penalized by having to repeat courses.

The number of required elective courses is also reduced from four to three. In addition to the reduction of credit hours and the universality of the new program, chief features include the following:

• Students can take the required two-semester history of civilization course in any sequence and from different departments. This gives them more freedom in scheduling classes and avoids delays caused by having to wait for certain instructors and certain times.

• The new program offers more intensive sequences of courses as alternatives to the core classes. History majors, for example, could take History 120 and Political Science 110 (or Economics 110) instead of American Heritage, or science majors could take specified rigorous physics, chemistry, or geology courses rather than Physical Science 100.

• The foreign language/advanced math requirement will add a music equivalent. This is not “an easy way out,” says Geary. The music alternative will easily require as much effort as mastering a foreign language, but it will make available an additional “language of learning” to meet varied student interests.

Beginning in September this year, all entering students (with the exception of some music and design majors) will be on the new program, unless they petition otherwise. Continuing students will also have the option of choosing the new program. In the fall of 1996, all entering students will be on the new program.

—Carri P. Jenkins

Hanging on to Our Freshmen

Nine hundred members of the BYU faculty and administration have a message for this fall’s incoming freshmen: Welcome to BYU.

But their message runs much deeper than words. These 900 volunteers, a part of BYU’s Freshman Faculty-Mentor Program, are committed to helping the 1995 freshman class make it at BYU.

Now in its second year, the program is one of many initiatives to help BYU students graduate. Upon learning that BYU loses 20 percent of its freshman class during that first year, not including those who “stop-out” for missions, a Freshman Year Experience Committee was organized. Among other proposals, the committee recommended that BYU adopt a freshman mentor program.

The university was also concerned about the four-year attrition rate, which has historically been near the 50-percent mark, the average of public schools. And it was worried about the students who do stay and yet are dissatisfied.

“Both national and institutional studies confirm that most freshmen decide to stay or leave within the first eight weeks of college,” says Gary L. Kramer, associate dean of Admissions and Records, who along with John Tanner, associate academic vice president, has taken a special interest in BYU’s freshmen.

“These early weeks are then pretty decisive,” says Kramer. “They constitute a bonding period with the institution.”

With this in mind, the university has added new programs, strengthened existing ones, and redoubled its efforts to inform students about the assistance available to them.

One such program is New Student Orientation, which has been going on for several years. This year, however, there will be no charge for the three-day event, with the university picking up the tab for everything from a barbecue to an extravaganza to seminars on financial planning to a parent’s orientation meeting. “This funding was authorized to see if it would increase participation in orientation,” says Tanner. “We don’t want any student to miss it because of expense. Bonding with BYU begins at orientation.”

Before this orientation ever takes place, however, BYU hopes to reach as many incoming students as possible through the Orientation Fireside program. To help make the move to college life a little smoother, Admissions and Records trains several hundred upper-class students who meet with BYU’s new enrollees in their own hometowns.

But this alone—even combined with the many other programs run through the Admissions and Student Life offices—is not enough, says Kramer. “What we have learned is that what students need the very most is a name. They need to know the name of one faculty member who knows their name and to whom they can turn for help.”

Through the faculty-mentor program, students have at least three contacts with a faculty member in the first eight weeks of school. Once by mail before they arrive on campus, once at the New Student Orientation, and at least once more during those early weeks.

An extension of this program is the BYU Freshman Academy, which was organized, in part, to help students and faculty get to know one another personally. It is a voluntary, open-admission program, and all entering freshmen who have been accepted to live at Helaman Halls or Deseret Towers are eligible to apply.

Groups of students in the Freshman Academy live near one another and take up to eight hours of regular on-campus introductory courses together during the fall and winter semesters of their first year. Academy instructors are encouraged to coordinate assignments and exams. They also frequently visit and eat with the students in the residence hall cafeterias.

The benefit of living in a Freshman Academy community, says Tanner, is that it breaks the large university into smaller, more student-friendly units and creates an environment that enhances learning outside the classroom.

“BYU is very serious about improving the freshman experience,” explains Tanner. “I remember when the administration shared with the board of trustees our concerns for the freshmen and our plans to help them. Later, an apostle closed the meeting by praying that the Lord would ‘bless the freshmen at BYU.’ His phrase has become our watchword.”

For more information about New Student Orientation, which runs from Aug. 31 to Sept. 2, please call 1-800-290-BYU1 or (801) 378-3641.

—Carri P. Jenkins