ROOTED AT BYU

Recent students may not realize that BYU’s present campus was once full of fruit. “Basically the whole hill was orchards,” says Roy Peterman, grounds maintenance director. “That’s why the canal goes through the main campus.” Like many of their Depression-era classmates, my grandparents picked apples and peaches in those orchards; for their labor they received 25 cents an hour and, sometimes, fruit for their table.

Edwin J. Butterworth, former director of public affairs for BYU, remembers when the land where the administration building now stands was part pear orchard, part tomato patch. He says the Heritage Halls dormitories are built on acres that once supported horses, cows, sheep, and a yellow farm house.

It’s good to remember that the land is arable.

In researching this issue that looks back at BYU during the 20th century, we editors have been reminded of the university’s rural origins and of the fundamentally agricultural nature of the whole enterprise. Things grow here–petunias, dairy herds, patent-worthy discoveries, magnum opuses. And people.

In about 1935 my grandfather, Albert Francis Bahr, helped plant the pines that now tower above the Heber J. Grant Building, which was then BYU’s library. As a student I walked near those trees perhaps hundreds of times without realizing that they were a tangible link to his young hands and my family heritage. Grandpa was the first in his family to–literally and figuratively–put down roots at BYU.

Drawing from readers’ memories as well as from BYU archives, the time line that follows, like the university history it attempts to capture, is the product of many minds and generations. From Alfred Kelly’s vision of future “temples of learning” to Janie Thompson’s decision to head the Program Bureau, the history of BYU is replete with stories about how a pivotal idea laid the foundation for future greatness. To paraphrase the Apostle Paul, one plants, another waters, God gives the increase. Many hands have built and planted at BYU. And we keep harvesting.

Today there is still plenty of fruit on campus, though none of it is grown for human consumption. According to Peterman there are ornamental pears, crab apples, Vesuvius plums. There are wild apple trees on the hillside below the Maeser Building. My most memorable personal contact with campus fruit came from stepping on and around fallen ginko fruits on the sidewalks near the Widstoe Building. But I have also loaded my pockets with tiny orange berries from the bushes that line the path from the Tanner Building down to Helaman Halls. They were ammunition; we waged berry wars with the guys in our freshman ward.

Whether your roots at BYU grew during an apple harvest or a berry war, we hope this time line and the articles that follow will help you remember those who planted for your generation–and taste again some of the fruit BYU offered you.

THE FIRST Y DAY

BYU’s school symbol found its way onto a mountain because of fierce rivalry between classes. The class of 1907 initiated the conflict by whitewashing their graduation year on the mountain–in the spring of 1906, when they were juniors. Naturally the senior class had to destroy those impudent numbers, and they dished out retribution by chasing down some of the offenders and shaving their heads.

In an effort to keep the peace, administrators decided to paint the school’s initials on the mountain instead. Nearly all the men on campus showed up to help with the whitewashing, which would become an annual springtime tradition. Women didn’t work on the mountain during the early years, but they participated in Y days by making lunches for the men and planning evening festivities.

Harvey Fletcher, a student (class of 1907) who had helped survey the letters B, Y, and U on the mountain, recalled that first Y Day:

The students stood in a zigzag line about eight feet apart stretching from the bottom of the hill to the site of the Y. The first man took the bag of lime, sand, or rocks, and carried it eight feet and handed it to the second man. The second carried it another eight feet and handed it to the third man and thus the bag went up the hill, each man shuttling back and forth along his eight-foot portion of the trail. All the students started with enthusiasm as they expected to be through by 10 o’clock a.m. But it was a much bigger job than anyone expected. It was 4 p.m. before the Y was covered and then by only a thin layer. So no attempt was made to cover the other two letters. It was very hard work and most of the boys had had no breakfast and no dinner. No one dared to quit as it would break up the line. In the afternoon it was more than some of them could take and they fainted and had to be helped down the hill. I am sure those who worked in that line that day will never forget it. (First 100 Years, vol. 1, p. 482.)

CONTROVERSY ON CAMPUS

Issues of academic freedom at BYU first arose early in the century. In about 1908 a few newly hired professors, eager to improve the university’s reputation, began to promote the latest developments in science and philosophy. A biology professor allegedly taught evolution not as a theory open to debate (as it had been discussed on campus before) but as an indisputable fact. A philosophy professor taught “rational exegesis,” a method of interpretation that discounted “impossible” Biblical stories, considering them myths or literary devices. Others also advocated “modernist” ideas. The professors involved were some of the university’s most impressively qualified faculty, and they had considerable support from their students and colleagues.

In 1955 students welcome the New York Philharmonic, which came to Provo as a part of the Lyceum Series.

BYU President George H. Brimhall reportedly began to worry about the effects of these ideas when some students told him “they had quit praying because they learned in school there was no real God to hear them” (First 100 Years, vol. 1, p. 421). The superintendent of Church schools, Horace H. Cummings, was even more concerned, and in 1911 he brought the matter before the Church Board of Education.

The board gave three professors an ultimatum: Stop teaching those theories so vigorously or leave the university. The campus was shocked, and most of the college students signed a protest petition. Declining to alter their teaching, the professors involved all eventually left BYU, though others of their colleagues, philosophically sympathetic but less outspoken, stayed.

Of the crisis Brimhall wrote: “There are some people who predict the death of the college if these men go. I am ready to say that if the life of the college depends upon any number of men out of harmony with the brethren who preside over the Church, then it is time for the college to die. . . . The school follows the Church, or it ought to stop” (First 100 Years, vol. 1, pp. 430–431).

HIGH CULTURE IN PROVO

From the 1901 visit of educator John Dewey to the 1994 visit of Lady Margaret Thatcher, BYU has hosted some of the century’s most influential people. Today experts and politicians typically come to campus as part of the Forum series, while performers are scheduled through the College of Fine Arts and Communications. But during most of this century, celebrated visitors of all types came under the aegis of the Lyceum Series.

Created in 1903 to enrich students’ cultural education (and for years coordinated with the Provo Community Concert Association), the series owed much of its quality to finance professor Herald R. Clark, who headed the program from 1913 to 1966. He followed the tours of cultural icons and famous musicians, and when they came anywhere near Provo, he booked a performance, often for less than their usual fees. Because of his ingenuity and diplomacy, BYU students heard first-class performances when Provo was even smaller and more out-of-the-way than it is today. After Clark’s death the Music Department carried on the tradition; though the name lyceums was last used for the 1982–83 season, the series continues.

Literary celebrities who spoke as part of the Lyceum Series include Art Buchwald, Pearl S. Buck, Robert Frost, Helen Keller, and Carl Sandburg.

The series also brought to Provo such world-renowned musicians as violinists Jascha Heifetz and Fritz Kreisler; soprano Leontyne Price; organists Marcel Dupre and Karl Richter; pianists Vladimir Ashkenazy, Bela Bartok, and Sergei Rachmaninoff; and such acclaimed choirs and orchestras as the Vienna Choir Boys, the King’s Singers, the Boston Symphony, and the Berlin Philharmonic.

CLASSES IN THE ASPENS

In 1921 a donor gave BYU 10 acres on the back of Mt. Timpanogos, and the Alpine Summer School was born. At the first session, held July 14 to Aug. 19, 1922, students and faculty lived in army tents, but within a few years dorms and classrooms were built and the university leased 80 additional acres from the U.S. Forest Service. The curriculum had a decidedly mountain flavor and typically included courses in art and the natural sciences. The program remained popular until wartime shortages forced its closure in 1942.

RUNNING TO CLASS

Students dashing between classes on upper and lower campus turned the Maeser Hill stairs into a thoroughfare.

BY ALBERT D. SWENSEN, ’37

Our campus really consisted of only four buildings–two on the lower campus, now known as “Academy Square,” and two on the upper campus, then called Temple Hill. . . . By some special ingenuity, whoever scheduled the rooms for the classes was able, with unerring precision, to stagger the classes of almost every student in the school on alternate hours between the two campuses, necessitating the trip–the 10 minute dash–between upper and lower campus by the maximum number of students. I don’t know to this day how the scheduler did it. To those of you who think jogging is a modern phenomenon, let me say we wrote the book. The only difference is that we did it in our best clothes. (“Of a Simpler Time and Place,” BYU Today, November 1990, p. 42)

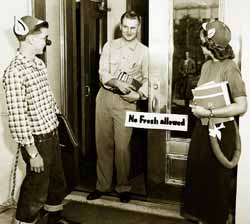

THE FATE OF FRESHMEN

The transition to college life has never been painless. But along with still-standard struggles like homesickness and general bewilderment, BYU freshmen who arrived a generation or more ago had to endure some hazing.

In the 1920s, for example, freshmen had to comply with all kinds of regulations during the initiation period: They were to use only the side and back entrances of campus buildings, repeat the College Song on demand, carry books, run errands, and generally serve the upper classes.

“Back then a freshman would not have dreamed of stepping out of line with anything that was sanctioned by the student body for fear of serious ridicule,” says Ted C. Hindmarsh, ’69. “For example, I had an uncle who was ill and couldn’t participate in Y Day one year. And they came and shaved a block letter Y in his head and painted it with iodine. For a week he had to walk around with this red letter Y on his head because he didn’t go to Y Day.”

But a freshman’s most common and visible duty was to wear a beanie. During the 1930s this cap was green and bore the letters “F-R-O-S-H”; later it was blue and white. “As an incoming freshman I remember having to purchase a small blue and white cap,” says Doug Nicholes, ’48. “On the visor you printed your name in big letters. The story went around campus that if a freshman was caught without his cap he would be tossed in the botany pond.”

Though it has died out today, the tradition of beanies and dunkings persisted into the 1960s, as the 1962 Banyan affirms: “Sighs of concentration turned to sighs of relief as weary freshmen filled out the last of an almost endless stack of cards and papers. Even a cool, involuntary plunge in the botany pond for those who neglected to don beanies was relaxing after the battery of tests they had faced” (p. 251).

SURVIVING THE DEPRESSION

In 1931 when Wilford Lee (’34, MA ’37) first registered at BYU, he recalled, “The school was struggling. They were still accepting gallon jugs of black strap molasses from the Dixie students as part payment on the student’s tuition. . . . I will always remember the Y as the poor man’s school; and since I was one of the poorest of the poor, I will always remember those days as a real struggle for existence” (First 100 Years, vol. 2, p. 258).

Many students who came to BYU during the 1930s might say the same. Though earlier students often boarded with local families, poverty forced most depression-era students to economize by “batching”–cooking and keeping house for themselves.

“We lived on the cheapest food that we could buy,” remembered Wilford E. Smith, MA ’48, who attended BYU as an undergraduate in 1939. “Skim milk, at five cents a gallon, along with potatoes, formed the base of our diet. . . . More than once we boiled the same soup bone, which we could pick up from a butcher for almost nothing, three different times in order to get all of the food value out of it. The soup made from the third boiling wasn’t very appetizing. That could be called living in poverty, but it was living, and we had a lot of fun along with our worries.”

The university wrestled with its own financial challenges–including a 22.5 percent pay cut for faculty and the recurrent threat of closure. Yet, partly because most Church junior colleges had closed by 1933, BYU enrollments increased 50 percent during the 1930s. By using federal grant money to fund hundreds of campus jobs, and by reaching out in other ways, faculty and administrators did what they could to help students who struggled.

“In those tough times, the university often allowed a student to register if he signed a note to have the tuition and fees paid by the end of the quarter,” said N. Laverl Christensen, ’37. “But the policy was changed and you had to have a down payment of at least $10. Somehow I wasn’t aware of that. My payday was a week or two away and I came to the registration window without any money. ‘Go and see President Harris at his office,’ I was told. There were a few students ahead of me. When I got to speak to the president he listened briefly, then pulled a $10 bill from his pocket and said as he shook my hand, ‘Go register.’ I didn’t waste any time paying him back when I got the money. I’ll always believe he had his pocket full of $10 bills that day.”

BYU AND WORLD WAR II

BY ORIN D. PARKER, ’48

It was easy in the fall of ’41 to forget that Europe was occupied and England was fighting for its life. I was a freshman, for the first time deep into religion and literature. But my most fascinating course was a diplomatic history of the United States, taught by aging professor Christen Jensen. He’d served as a junior diplomatic officer in the American delegation at the Treaty of Versailles, where we let our allies play politics with the First World War’s victory.

The Uinta Theatre on Center Street was the smallest of the three cinemas where I worked. On Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, after a brief appearance at an off-campus ward Sunday School, I had to open the theatre, pop the popcorn, and ready everything for the Sunday matinee at 1 p.m. The newsreel that always preceded the feature film showed the Japanese delegation smiling their way through meetings at the State Department and at the White House.

About 20 minutes into the picture, my friend called the box office to report the attack on Pearl Harbor. We were stunned. For a few minutes we listened to the startling bulletins on the portable radio in the cashier’s cubicle. I decided we had to let the audience know, so I hand-printed a slide that could be projected: “Japanese planes attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii today.” A few customers got up and left, and others came out periodically to get updates as the reports gave details of the disastrous bomb damage. It was so unbelievable, so shocking, that we didn’t really comprehend how much of our world had changed in that hour. That night after work my friend Bill and I walked up and around the campus, talking of what this would do to our lives.

On Monday, Dec. 8, a special assembly was called in the Joseph Smith auditorium to hear President Roosevelt’s message asking Congress for a Declaration of War. I can still hear Roosevelt’s ringing denunciation of this “day of infamy.” We had weeks of discussion about these astonishing events in our diplomatic history class.

A few students left school immediately. But the advice from government, church, and the university was to wait and see where we’d be needed. I waited till the end of the year before enlisting in the Navy. Thirteen months after Pearl Harbor I was in the Solomon Islands.

The drama of those December 1941 days is still with me. Remembering now, I think I was relieved. Life’s immediate decisions would be made for me. I could postpone the important plans that were so difficult to make, the plans that the Y would solidify for me when I returned three and a half years later, with the GI Bill providing enough so I wouldn’t have to work. Coming back to the Y in ’46 was one of my best memories of World War II.

THE DORM-BUILDING BONANZA

After World War II, BYU presidents Howard S. McDonald and Ernest L. Wilkinson worked hard to provide housing for the rapidly expanding student body. In 1946 McDonald obtained 26 war surplus buildings and turned them into Wymount Village for 200 married couples and “D Row,” which housed some 300 single men. Though considered temporary, these dorms were used until the early 1960s.

Wilkinson initiated an ambitious dorm-building program soon after he arrived as president in 1951. The first 16 buildings in Heritage Halls (intended for women) were completed in 1953 and another eight were finished in 1956. In 1957, 150 homes were brought from Mountain Home Air Force Base and put in place as Wyview Village for married students and faculty. Next came Helaman Halls, for men (1958–59); Wymount Terrace, for married students (1962–63); and the first five Deseret Towers dorms (1964).

Then, though his academic building blitz continued, Wilkinson stopped trying to meet the demand for campus housing. He had hoped to provide space on campus for 60 percent of the student body, but enrollment climbed faster than new construction could. Another Deseret Towers building was added in 1969, and a final Helaman Halls dorm in 1970. And in 1971, when Wyview Village was replaced by the Marriott Center parking lot, the university compensated by creating a mobile home park for 150 families. But it would be 20 years before BYU built substantially more student housing. Units were added at Wymount Terrace in 1992, and in 1998 the Wyview Park apartments (housing 426 families) replaced the trailer park.

FOOTBALL: Y FIRST DEFEATS U

BY PAUL E. FELT, ’42

Over a 20-year period University [of Utah] defeated BYU in football each year, except for one tie game. During the school year of ’41 and ’42, BYU won their first game. . . .

The totally unexpected victory caused a great turmoil. Our students rushed down to the field and tore down the goalpost. Needless to say, I, as student body president, was right in the heart of the whole activity. They called the fire department out and were spraying large streams of water on us to break up the activity. In addition to BYU students, there were a lot of University of Utah students trying to oppose and block our efforts to pull down the goalpost.

Some University students identified me as the student body president, which prompted a few of them to grab me and pull off my pants. The BYU students then walked with me into the dressing room while I put on a pair of football pants. After 30 or 40 minutes they finally brought everything under control.

I never did recover the pants they removed, so I went home to my mother and father in Salt Lake wearing BYU football pants. They asked where I’d been, and I told them we had just completed a great game with the University of Utah and they needed another man so they put me on the team, which of course was a falsehood. Nonetheless, for a few minutes my dear mother believed me.

REGISTRATION WOES

During Ernest L. Wilkinson’s tenure as university president, BYU’s student body expanded from 4,004 (February 1951) to 25,116 (September 1971). Getting all those students registered for classes was a mammoth administrative task and often traumatic for students.

“I arrived at BYU in the fall of 1960 with no car, no friends, and five strangers for roommates,” remembers Marilyn Durfee Elison, ’64. “So when my dad headed back to our hometown of Almo, Idaho (population about 300), I was distraught.

“Registration in the Smith Fieldhouse was the first trial I encountered at BYU. I stood in line for hours in the morning just to get into the Fieldhouse. Once inside, you had to get a class card for each class on your schedule, but after waiting all that time all of my classes were full–all the cards were gone. When that happened, which it frequently did, you had to go back to your adviser to work out another complete schedule and then try again. It was just a nightmare.

“Some classes required auditions or permissions as well, so for me, a music major, registration was an all-day affair. After all day in there, I finally got a working schedule and walked out the door. Well, once you left the Fieldhouse, you couldn’t go back in unless you waited in line all over again. When I got outside I realized I didn’t have enough credits. I thought it was the end of the world.

“I was totally upset by that point, so I went back to my dorm room in Heritage Halls and just cried. Luckily, my dorm mother found me and explained that I could add classes. No one had told me that before. That took me on a runaround all over campus, even to offices at the old lower campus and at the Page School, but I finally filled my schedule.”

While preregistration (1972), mail-in registration (1976), telephone registration (1984), and Internet registration (1999) have freed later students from the card-registration ordeals their predecessors endured, this comment from the 1963 Banyanrings true for every student who has registered at BYU during the 20th century: “One aspect of registration never changed. Someone was always there to take your money” (p. 10).

FAD DANCES BANNED

“The monkey, the dog, the frug–everyone at BYU was doing them; that is, until President Wilkinson gave a controversial speech at the beginning of the year banning all fad dances. The student body split into two opposing camps, one arguing that such dances were indeed against Church standards, the other saying that there was nothing wrong with them. Discussions grew heated, and prejudiced letters to the editor filled the columns of the Universe until the issue was finally settled by a letter from President McKay. Verdict–No more fad dances. The decision brought the campus nationwide news coverage and encouraged comment on other campuses.” (1966 Banyan, p. 174)

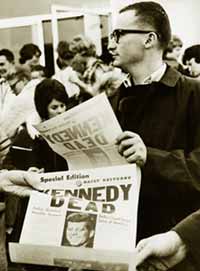

MOURNING PRESIDENT KENNEDY

BY REX ARNETT, ’61

None of us expected anything less than the total closure of the university on Monday, Nov. 25, 1963, in observance of the funeral of President Kennedy. . . . We were startled and shocked at the decision made by President Wilkinson to proceed with classes as if it were an ordinary day. . . .

Before sunup I drove my beat-up Volkswagen to the upper campus to conduct my university class. To my surprise most of the class showed up at 7 a.m., though we did little Spanish 321 Composition and Grammar that day. At 7:50 we dismissed, and I exited the Knight Building to cross the quad to the parking lot behind the HFAC, under construction.

This plaza characteristically at 7:50 was crowded elbow to elbow with professors and students headed for the first official period of the day. They usually spilled onto the grass, and those going completely across campus jostled to get ahead of the pack so as not to be late. Knowing the sentiment and, I might say, resentment that was brewing, I did not expect the plaza to be as full. But it was, and just as I started across, the BYU Carillon (the old electronic one mounted atop the ESC) started to play and the ROTC contingent started to

march from the library to the Smoot Building to post the flags. Usually no one paid any attention and indeed the color guard routinely was impeded in their march. But the flags, the hearing of the Star Spangled Banner, and the sight of their fellow students in uniform on that historic day simultaneously brought the whole throng to a complete halt. In the crisp fall air, we heard the footsteps of the guard and the voice of the commandant giving the orders, and we stood in absolute reverent attention. Probably there were several thousand in this quad or adjacent to it, but not one person moved except to salute or place their hand on their heart as the ceremony unfolded. On its completion the crowd moved slowly, reluctantly, to their classes as a truly sacred moment ended. . .

The early morning moments of reverence and respect for our nation’s fallen president will always be treasured among my cherished BYU experiences.

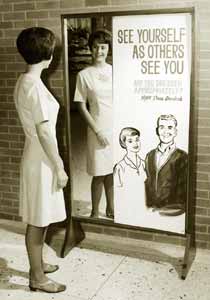

EVOLUTION OF THE DRESS CODE

“When I first came to the BYU I had a single suit. In those days all dressed for school as they did for Sunday School, in their best. Corduroys, jeans, weather beaten shirts, heavy shoes had their place primarily in the barnyard and field but not for high school or college.” So wrote J. Edward Johnson, ’15.

While grubby attire has never been appropriate at BYU, the definition of grubby has evolved with the styles. For example, during most of this century jeans were considered too grubby for class. Men were first allowed to wear jeans sometime in the early 1970s, but acceptable women’s attire was specifically “not to include jeans” until 1982. (Pants for women became permissible in 1971.) And official university publications continued to prohibit bib overalls until 1992, on the grounds that they were grubby attire. Cathy Davis, ’87, remembers that she “got in trouble from a professor for wearing overalls to class when there was about two feet of snow on the ground.”

Like the bib overalls exclusion, the “men must wear socks with shoes” rule was first specified in 1982 and dropped in 1992, when the dress code was substantially revised and shortened to reflect the language of the LDS Church’s “For the Strength of Youth” pamphlet. Perhaps the most celebrated result of that revision was the sanctioning of knee-length shorts.

Since they first were published, BYU’s dress and grooming standards have had plenty to say about men’s hairstyles–limiting lengths, outlawing beards, requiring the exposure of earlobes, defining appropriate sideburns, and discouraging mustaches. Since the 1992 revision, however, BYU’s official position on mustaches has been neutral, and a current club on campus celebrates the mustache as the “honor-code-friendly” facial hair.

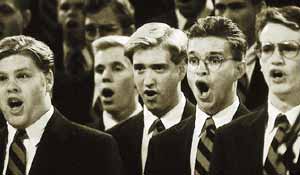

MEN’S CHORUS FOREVER

BY SUE QUACKENBUSH, ’93

During my first semester I made the firm decision that I was going to marry a member of the BYU Men’s Chorus. I had recently attended a combined choirs’ social event, and after being introduced to the Men’s Chorus as a whole, I fell totally and completely in love.

I was a Men’s Chorus groupie.

The very next semester I auditioned for and joined the BYU Women’s Chorus (and not only because we rehearsed just before the men did). Some of my choir buddies and I started staying after our rehearsal once in a while to sit way up at the top of the recital hall and listen. It didn’t take long before it became a daily ritual. After singing for an hour ourselves, we would justify staying another hour by pulling out some textbook or another and pretending to study. Dr. Wilberg was never fooled, I’m sure, but he never threw us out, either,

since we tried to behave ourselves.

Singing and listening to music became a life saver to me through my BYU experience. Those two hours I spent in the HFAC every day for two years were like a daily hiatus. No matter how rotten the day had been, it was a relief to put all in my backpack and just sing and enjoy the good music. Eventually I had to drop Women’s Chorus because of a class scheduling conflict. Still, every day as soon as my class was over (in the RB), I would hoof it up that obnoxious set of stairs on the west side of campus and run all the way to the HFAC so I could still catch as much of the men’s rehearsal as possible. Then, and only then, could I go home fulfilled.

I’m still a confirmed member of the BYU Men’s Chorus Fan Club. How could I not be, especially since I did achieve my “goal” and married a tenor? (I still go weak at the knees every time he puts on his red and navy blue striped tie!) Even though we no longer live in Provo, my husband and I have kept every tape of every performance he sang in while at BYU, and we’ve collected every CD produced since we graduated. And you can bet we listen to them almost every day.

GRIDIRON GLORY DAYS

Though BYU teams reached national prominence in basketball and other sports long before then, BYU football really came of age in the 1980s.

LaVell Edwards was made head coach in 1972, and his “quarterback factory” immediately started breaking records. By the end of the decade BYU was on top of the college football world. In 1979 and 1980 the Cougars had a combined 22–1–0 record and led the nation in total offense, passing, and scoring averages. Their ascension was complete at the 1984 Holiday Bowl, when BYU beat the University of Michigan 24–17 and crowned a 13–0 season with the national championship.

Five BYU quarterbacks have finished in the top three of Heisman trophy voting: Marc Wilson (1979), Jim McMahon (1981), Robbie Bosco (1984 and 1985), and Ty Detmer (1991) all finished third. Steve Young finished second in 1983, and Detmer won the trophy in 1990.

The team played in (and lost) their first bowl game on Dec. 28, 1974. But since 1978, when they faced Navy in the first-ever Holiday Bowl, BYU’s football team has had a bowl berth every year but two. Their first New Year’s Day bowl came in 1997, when they beat 14th-ranked Kansas State 19–15 on their way to a 14–1 season and a number 5 ranking.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Much of the information in these articles is drawn from the four-volume history of BYU, Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years (ed. Ernest L. Wilkinson, [Provo: BYU Press, 1975]). In-text citations use First 100 Years. Except for the comments from Ted C.Hindmarsh, gathered in an interview; Albert D. Swenson’s story, taken from a BYU Today article; and Marilyn Elison’s memories, provided by her daughter Megan Candre; all of the first-person quotes are from autobiographies or reader submissions and may be found in BYU archives.

PHOTO CREDITS:

Laie, Hawaii (p. 27), Jerusalem Center (p. 30), and Men’s Chorus (p. 31) by John Snyder, Lee (p. 30) by Merrett T. Smith; Holland (p. 30) courtesy BYU University Communications; Detmer, Bateman, academy and national championship (all p. 31) by Mark Philbrick; all others courtesy Harold B. Lee Library Special collections.

WEBMASTER’S NOTE:

Pages listed above correspond to those found in the hardcopy: Brigham Young Magazine, Winter 1999-2000.