Is Neil J. Reed (BS ’16) nuts, or does he just enjoy gathering them in his free time?

Reed’s foray into foraging—finding and harvesting wild foods—began simply enough, collecting fruits, nuts, and edible foliage. But

His archaeology class sparked the idea. He wanted to put the primeval hunter-gatherer lifestyle to the test—in an urban sort of way. He subsisted on locally foraged plants and free food from campus and church events, from extended family, and from roommate leftovers. “I didn’t really discriminate,” says Reed. “[Foraging] is finding food in the landscape around you,” he explains.

Did he make it all the way through fall and winter semesters?

“Almost,” says Jared J. Maxfield (BS ’14), Reed’s former roommate. Reed did take a girl out a date, on which he purchased dessert. In the end, Reed spent just $8 on food fall semester—the only money he would spend on food that entire school year.

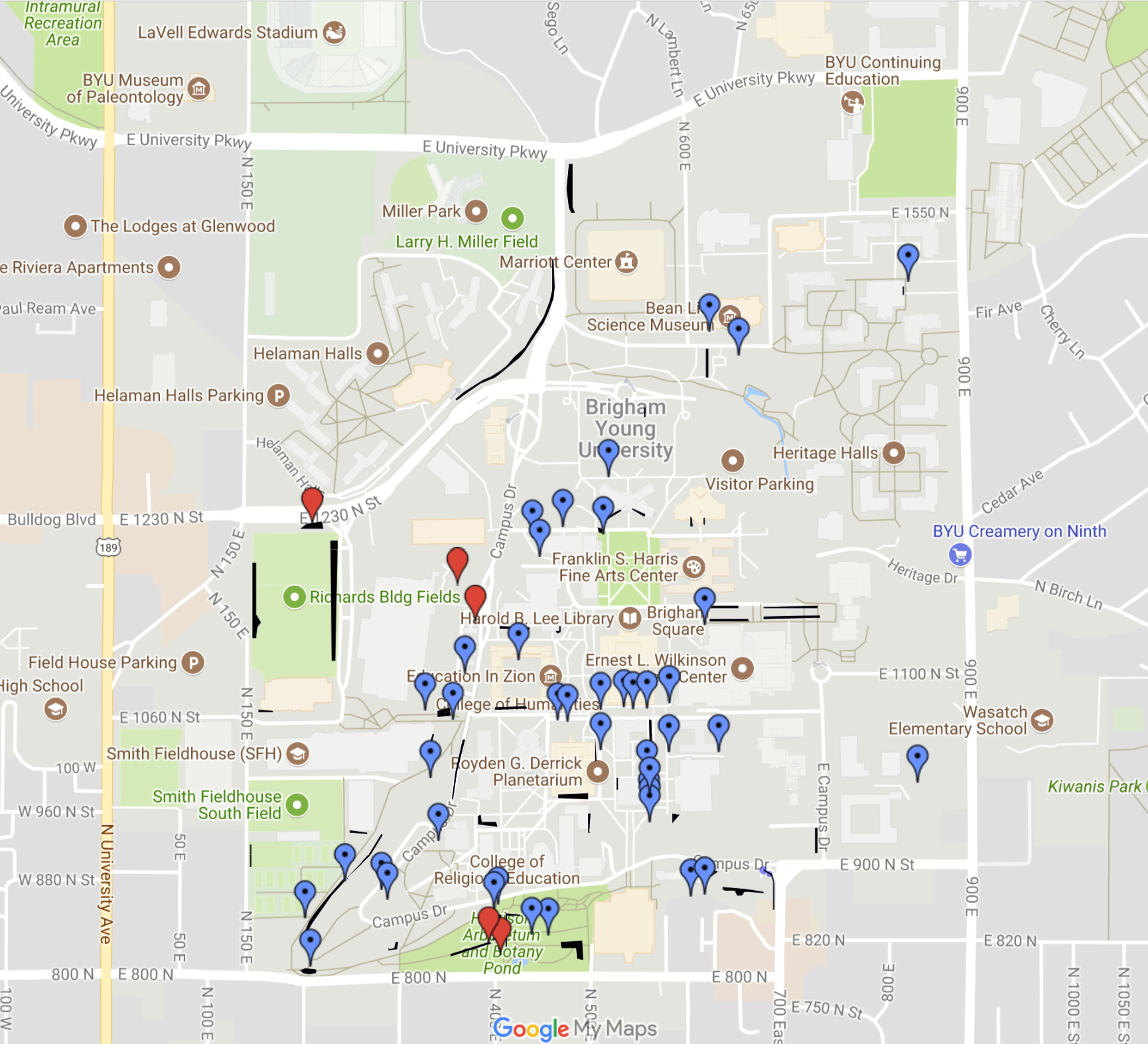

To aid in the experiment, Reed created a map of edible plants on and around campus, from the plums by the duck pond to the beechnuts by the Brigham Young statue.

Almost every tree on campus has something you can eat, says plant and wildlife sciences professor Thomas S. Smith (BS ’82, PhD ’92), who was an early source of inspiration for Reed. Smith collects acorns on campus himself. “Sometimes the police will pull up and ask what I’m doing. I love telling them,” he says. Each fall through BYU’s Bean Life Science Museum, Smith leads a foraging class, cooking what they can find, and he and his wife host “wild parties,” where the menu is all foraged—down to the juniper seasoning on the deer steaks. “People, if they make things, they get into it,” says Smith. “They own it, and it’s special.”

Reed echoes the sentiment: “Foraging makes you really appreciate all the work that goes into something.” Take acorn-flour bread: it can take an hour to process one cup of flour from acorns. “You have to do a Netflix binge to shell all those,” says Smith. With processed foods, there are so few steps for the consumer that most people don’t realize how intensive producing food really is, says Reed: “You don’t have to pick up anything, you don’t have to grow anything, and in a lot of cases you don’t have to cook anything.”

Being removed from food production can also make people more wasteful, Reed argues—and no one could accuse him of anything but thrift. As Maxfield recalls, “one time [Reed] got, like, 85 hot dogs from an activity, and he just brought them home and froze them and was eating them for the next month and a half.”

Still, at the end of Reed’s first semester of urban foraging, some were unimpressed. “My friends said ‘Oh, it didn’t count,’” says Reed, because he was gathering processed foods, like the hot dogs—not raw ingredients. “So I started thinking about what the most pure form of that project could be.”

The criticism compelled Reed, who Maxfield calls “an adventurer at heart,” to make a drastic but long-planned move: he would test his wild-foraging expertise by living exclusively off of BYU-campus plants and camping for one full week during Christmas break. “Some people thought I was going to die and said I shouldn’t do it,” Reed laughs, recalling that some friends gave him the dos and don’ts of eating roadkill, in case times got desperate. But that only increased his determination.

In preparation for the challenge, Reed laid out 100 pounds of acorns to dry in a field next to his apartment complex only to have them stolen. “I had never seen him so angry,” says Maxfield. “‘The deer! They ate half of my acorns!’ And from then on, the deer on campus were his mortal enemies.” Reed says his feelings are a simple nod to the food chain: “I don’t really like deer because they compete for the same food.”

Despite the burgled nuts, Reed’s main food sources for the week were acorns and hawthorn berries, which he dubbed “glueberries” for their taste—“strawberries mixed with glue stick.” They quickly became hard to stomach. “I needed to keep on eating them,” he says, “but I really, really, really didn’t want to.” Still, he maintained willpower of steel. “We had this ward Christmas feast that he came to,” chuckles Maxfield, “and he brought this bowl of glueberry mush. And so we’re eating mashed potatoes and turkey, and he’s sitting there with a look of bitter contempt.”

The weeklong foraging adventure “was a lot harder than I thought it would be,” Reed says. He lost some weight during those seven days, which he attributes to a lack of food variety and quantity—and to frigid temperatures. Something else surprised him too: “I’m more reliant on other people than I thought,” he says, for everything from food processing to social support. He details eating his first post-challenge meal on his blog, Wilderness of the Mind: “I seem to recall telling God I was ‘thankful for industrial food systems.’ . . . I reveled in how much nutrition just one bite of the bread yielded, and just how easy it was to get those calories. It’s something I’d never really understood until that moment. As a society, we’re really good at getting calories into a ready-to-eat form.”

That’s not to say he has given up foraging. Since graduating last year, Reed has taken his gathering international, scrounging up delectables along his travels in South America, Asia, and Europe. With the right knowledge, every landscape is full of resources, he says—every leaf, nut, berry, and tree imbued with new meaning for the humble gatherer. While his BYU experiments were “extreme,” Reed says foraging really “comes down to being more aware of our surroundings and appreciating what God has made for us.”

In a May blog post, he promises to document his latest adventures. “In the meantime,” he signs off, “take care of yo’self, eat a dandelion or two and don’t forget to wash your socks.”

Want to Start Foraging?

Plant and wildlife sciences professor Thomas S. Smith’s (BS ’82, PhD ’92) passion for foraging was sparked in the BYU class 30-Day Survival, offered back in the ’70s. “We called it the world’s-longest fast Sunday,” he says. Now he’s the campus expert on the subject. Here’s advice for beginners:

1. Look at the plants in your own backyard and start learning about them.

2. Never do anything with a plant that you cannot positively identify.

3. Talk to knowledgeable foragers and take classes on edible plants.

4. Try the serviceberries—Smith’s favorite Utah-native plant. “They have another kind of flavor people don’t know about—kind of nutty almond mixed with a blueberry,” he says. “And they’re so abundant, you can eat them until you’re full.”