A century ago BYU took on a worldwide pandemic that upended campus in remarkably similar ways to COVID-19.

While the effects of COVID-19 on campus may feel unprecedented, canceling classes, sending students home, and sidelining sporting contests have all happened before—just over a century ago.

“SPANISH INFLUENZA EPIDEMIC—SCHOOL CLOSED. HALT!!” was the command that “came ringing through the halls of the Brigham Young University,” according to the Oct. 16, 1918, edition of the White and Blue campus newspaper.

As World War I ended, returning soldiers and citizens worldwide faced a new deadly enemy: the 1918 influenza. In total its three waves infected half a billion people—approximately a third of the world’s population—and eventually claimed an estimated 20 to 100 million lives.

But in mid-October 1918, the White and Blue staff writer wasn’t too concerned: “The situation is not serious, . . . and the enforced vacation will probably not be longer than a week.” The article continued, “The time need not be lost,” and encouraged students to pick apples, dig beets, or mix cement for a new mechanic-arts building on Temple Hill.

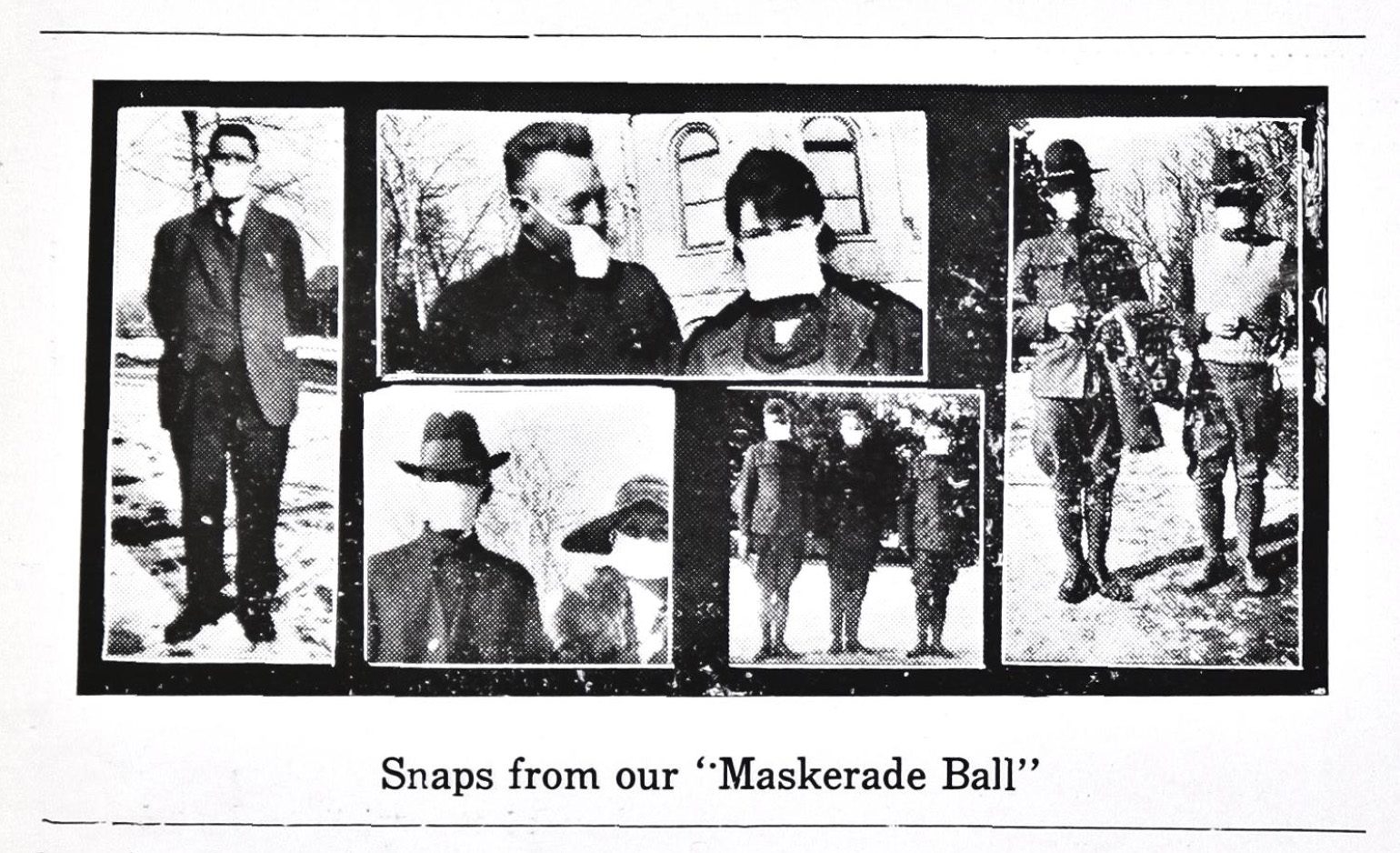

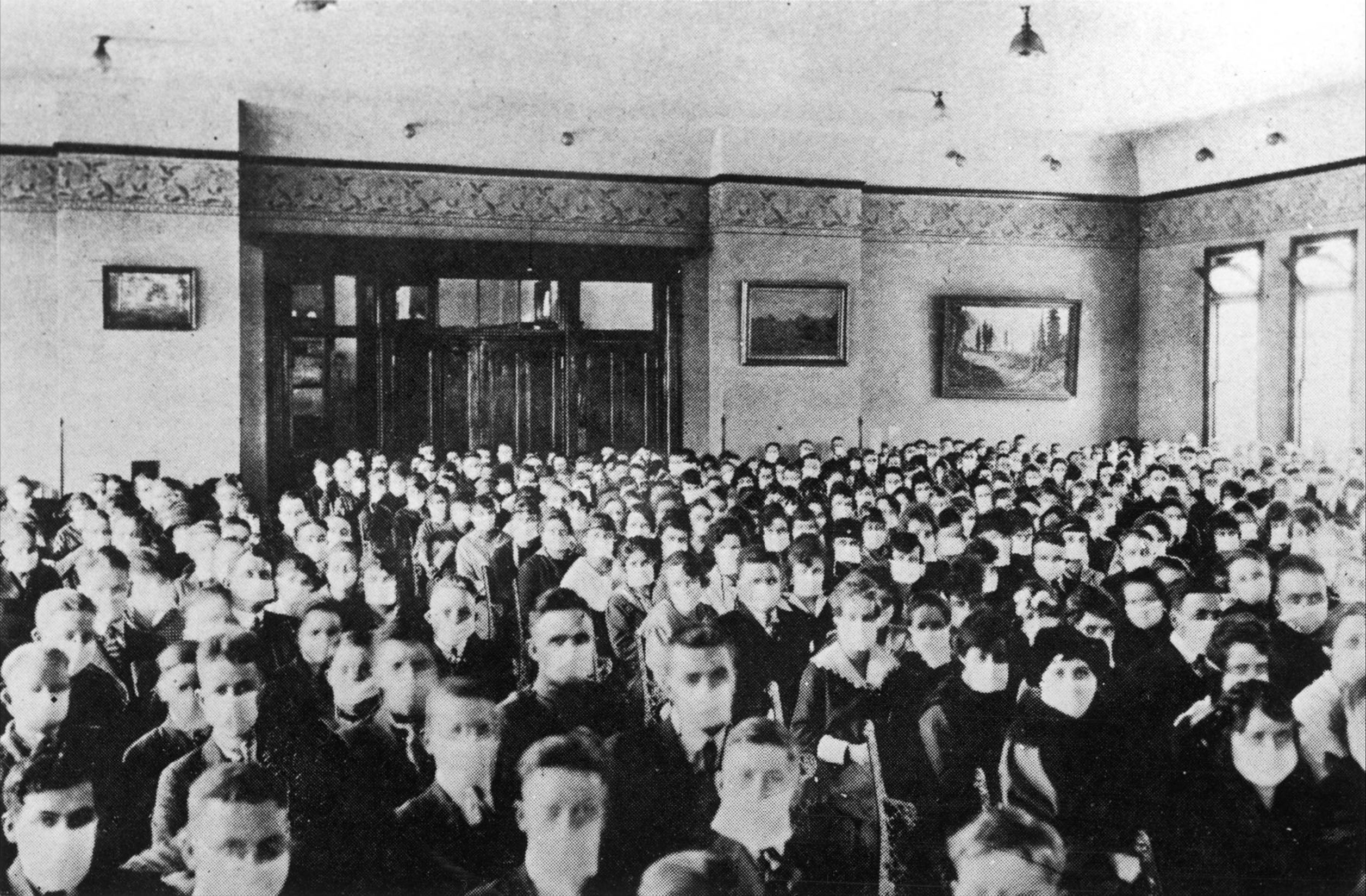

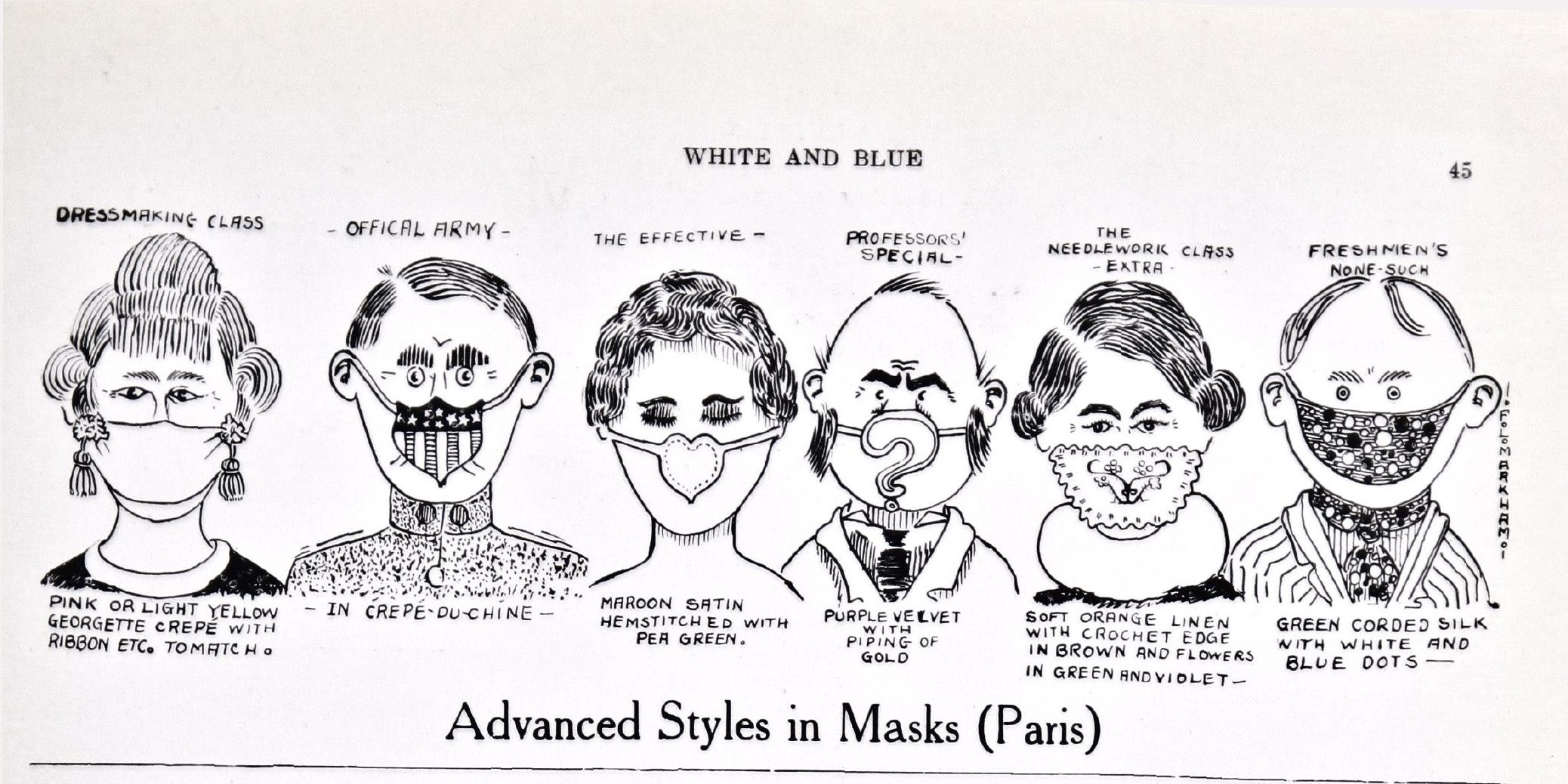

In the end the flu pandemic closed campus until January 1919, canceling three months of classes, athletic events, dances, debates, and theater productions. As BYU students returned for winter 1919 classes, many restrictions on activities remained in place, and they found it difficult to recognize friends through flu masks. And among those missing were President George H. Brimhall and a dean, both quarantined at home with their families. According to a Jan. 19 White and Blue editorial, “The school is doing its utmost in compliance with the city rules, and to insure safety here. Large gatherings are positively avoided.”

To that end, the public had been kept away from President Joseph F. Smith’s funeral in November and the Church’s April 1919 general conference would be moved to June. Likewise, travel and crowd concerns kept BYU fans from accompanying the men’s basketball team to February’s rivalry game up north, opting for safer “long-distance cheering.”

Every week for months, a few obituaries memorializing students from the university, high school, and training school appeared in the White and Blue. By summer 1919 the flu waves had finally passed. “Hundreds died in Utah County, many families being wiped out,” according to Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years.

With curtailed classes and social activities, the editorial in the Feb. 5, 1919, White and Blue suggested students polish up on school yells, study current events, read scriptures, take brisk walks, and write letters, saying, “The possibilities of these days, although different, are real. Make them days, students. Make each one stand for something achieved. Don’t let these masks hide everything in sight.”