By Peter Gardner, ‘98

Ninety percent of U.S. citizens claim to believe in God and the hereafter. Fifty percent say they attend church regularly. Nearly all, to some degree, participate in mass media–newspapers, books, movies, television, the Internet–and the popular culture these communication devices create. But because of religion and media’s often opposing viewpoints on core values, their intersection in society has at times resulted in passionate clashes. Thus when Americans think of religion and media, it is often the culture wars that come to mind–picket lines, protests, and accusations of censorship. A BYU professor cautions, however, that this perspective overlooks the ways these old opponents sometimes work together.

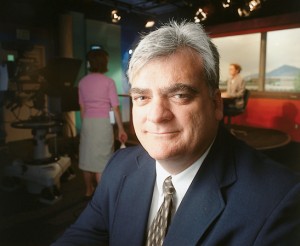

BYU communications professor Daniel Stout has helped create a new field of inquiry, one that uses both sociology and mass communications research methods to examine how religions use print, television, radio, and the Internet to meet their spiritual goals.

“The culture-war metaphor has spawned a sort of dichotomy between religion and media,” says BYU associate professor of communications Daniel A. Stout, ’79. “But religions participate in popular culture as much as they criticize it.”

And although the topic has been the focus of heated discussion for centuries, there has been almost no scholarly inquiry into it. “If you open any of the textbooks in mass media and society, you don’t see much about religion,” says Stout. “But religion is a very salient element in American society and in many nations around the world.”

The coeditor of two books and a recently announced journal on religion and media, Stout hopes his efforts will help fill the void of research and move the discussion of religion and mass media beyond the level of culture wars.

Exploring a Research Frontier

“Dan has helped lay out media and religion as a field,” says Stewart Hoover, a professor and associate dean in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Colorado at Boulder. “His particular take has been to link studies of this phenomenon to the social sciences.”

Stout’s first major contribution to the field came in 1996, when he and Juddith M. Buddenbaum, a Lutheran professor of journalism and technical communication at Colorado State University, teamed up as coeditors of Religion and Mass Media. The pioneering volume led to the publication in January 2001 of a second book, Religion and Popular Culture, which considers religions worldwide. The success of these books inspired the creation of the Journal of Media and Religion, which will be edited at BYU and will be the first scholarly journal exclusively devoted to the study of religion and mass communication.

“It’s an exciting thing,” says Stout, who is head of the religion and media interest group of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. “It’s a research question that hasn’t been fully examined, and there’s a small but growing group of researchers looking at it.”

Because so little has been done on the topic, it’s no surprise the books and journal contain more questions than conclusions. With research from scholars of sociology of religion and of mass communications, these interdisciplinary works explore a diverse range of questions: How do specific technologies like radio, TV, and the Internet affect religious worship? How do media depictions of religious groups affect viewers’ perception of them? What roles do religion and religious values play in determining what is portrayed in the media and how media is received? How do church leaders deal with the challenges and take advantage of a society saturated with media influence?

Because of the significance of these questions for a diverse range of readers, the books have been widely used by scholars, graduate students, students in seminaries, clergy, and, to a lesser degree, interested laity. “It’s simply a topic that a lot of people are interested in,” says Stout.

Hoover says these early works at the frontier of religion and media research have quickly become standards in the field.

“I think our work has created interest and heightened awareness that religion is an important force,” says Buddenbaum, “one that needs to be taken into account in more traditional studies of media use and effects.”

Mediated Religion

Stout notes that while many religions, including The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, rightfully warn their adherents about the effects of unwholesome media, most also use media formally or informally to achieve spiritual goals.

This phenomenon is nothing new. Religion has been in print since Gutenberg’s Bible, and music and art have long been commissioned by religious groups. And as advances in technology have introduced new communications media, religions have found ways to make use of them. Religious radio stations, featuring both talk and contemporary music, can be found all over the dial. And with programming like Pat Robertson’s 700 Club, Touched by an Angel, and the Church of Jesus Christ’s award-winning public service commercials, viewers needn’t look long to find religion on the TV. More recently, the Internet has become home to countless official and unofficial religious Web sites, where viewers can find information and, in some cases, even be directed in worship. Stout says he hopes this research will help determine how such media presentations affect personal and collective religious behavior within religious communities.

The research also looks at the significant increase in what Stout calls “religious branding.” Examples include Chant, a hugely popular CD featuring Benedictine monks singing musical prayers; WWJD (“What Would Jesus Do?”), a logo found on sportswear, jewelry, and music for Christian youth; and the recent surge in books and literature for religious markets.

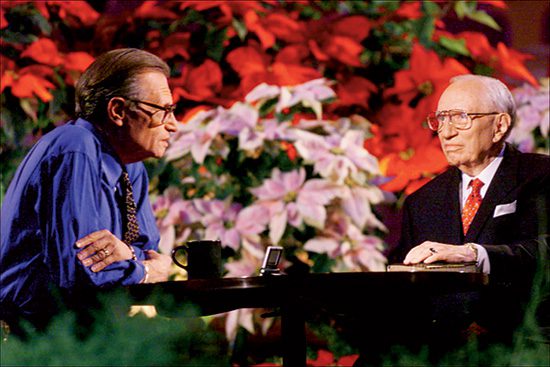

Stout and Buddenbaum’s research also considers religions’ attitudes toward news media. While some regard news media as secularized and adversarial, others have cooperated with these groups to disseminate information and create favorable public perception. He cites the Church of Jesus Christ’s efforts to provide journalists with information. “President Hinckley has seen the importance of meeting with media, being open, and disseminating information about the Church on a regular basis,” says Stout. “And that’s been very effective.”

President of the Church of Jesus Christ Gordon B. Hinckley, pictured here with radio and television personality Larry King, is an example of a religious leader who regularly works with the media to spread spiritual messages.

Stout is also interested in helping individuals and families use appropriate media to strengthen their religiosity. “I think these efforts will help us to be more media literate in the religious sense. By media literacy I mean developing the skills to use media in ways that are consistent with our religious objectives,” says Stout. “By looking at some of these questions more deeply, families will have more information to help them.”

And with the new journal and the growing number of scholars following Stout’s lead in this field, information on the complex relationship among religion, mass media, and popular culture is becoming increasingly available.

“Dan’s energy and determination have played a big role in creating interest in and publication outlets for studies of religion and the media,” says Buddenbaum. “He is a great ambassador for our field of study.”