BYU's Primrose International Viola Archive, named for eminent violist William Primrose (above, informs and inspires violists—and others—worldwide.

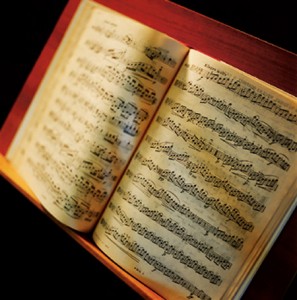

The viola, the underdog of the strings, is a peculiar musical instrument tuned a fifth below the violin. Properly played, the distinctive bottom string of a viola can bring unbidden tears to the eyes of an audience. But the viola’s position in the midst of the orchestra and the relative scarcity of major pieces written for the alto instrument has historically invoked a painful litany of jibes from higher-strung musicians.

But on the fourth floor of BYU’s Harold B. Lee Library, the viola plays second fiddle to none. In fact, the Primrose International Viola Archive (PIVA), with more than 5,000 collected works, is the most comprehensive collection of materials related to the viola on the planet, a great resource and retreat for those musicians most often trod upon.

A Violin With a College Education

David Dalton, a BYU emeritus professor of music, spent 20 years building the Primrose International Viola Archive into the most comprehensive collection of viola materials in the world. The archive started from the personal library of William Primrose, Dalton’s mentor and a former BYU lecturer. Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94.

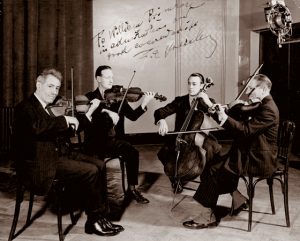

William Primrose, for whom the collection is named, was born Aug. 23, 1904, in Glasgow, Scotland. He began playing the violin at age 4 and continued until 1930 when he took up the viola with the London String Quartet. “I had become a violist full-fledged,” he writes in Walk on the North Side: Memoirs of a Violist. “I had burned all my bridges. I had walked the Damascus road, seen the light, repented of past transgressions, and turned to the viola.”

His conversion complete, Primrose became a polished performer and a persuasive proponent of the viola. According to David J. Dalton, a BYU professor emeritus of viola who interviewed the master violist extensively, Primrose was often asked about the difference between the violin and the viola. His long explanation later turned to something shorter that anyone could grasp: the viola is “a violin with a college education.”

Primrose recorded with the NBC Symphony under Arturo Toscanini, traveled as a soloist, and performed with orchestras throughout Europe and the United States. Primrose, according to Dalton, “is to the viola what Michael Jordan is to basketball—singular, one-of-a-kind, unique, virtuoso.”

Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94

Primrose has been called “the first star of the viola” and “the world’s greatest violist,” and for his musical accomplishments, Queen Elizabeth II granted him the title of Commander of the British Empire in 1953.

A viola pioneer, Primrose made the stringed instrument played by Beethoven, Bach, and Mozart more popular in modern times. A number of concertos were written specifically for Primrose, who became an accomplished arranger and editor of viola music himself.

Dalton, who studied under Primrose at Indiana University and collaborated on his memoirs, invited the virtuoso to Provo. Primrose accepted and spent the last years of his life, 1979–1982, at BYU as a guest lecturer in the music department.

With encouragement from Dalton, Primrose donated his personal library of annotated scores, manuscripts, recordings, letters, photographs, and other memorabilia to BYU. Then in 1981 the archive of the International Viola Society moved from the Mozarteum in Salzburg, Austria, to the Harold B. Lee Library. This relocation more than doubled BYU’s collection to over 2,000 viola scores, and the William Primrose Library became PIVA, now the official archive of the International Viola Society and the American Viola Society.

“Over the last 20 years, it has more than doubled again,” Dalton says. “Now we have about 5,000 viola scores that are in the open stacks. We have another 1,000 that are yet in process, being catalogued or bound, or are in the music special collections.”

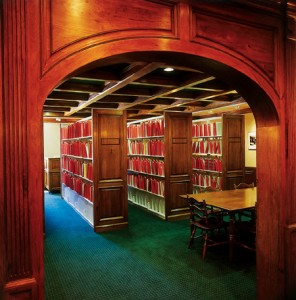

The new space for the archive was dedicated in March 2002, celebrating the 25-year efforts of Dalton and gracious donors, and is a place both pleasing and practical.

Inspiration and Resource

Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94

Through the door, upon which the likeness of a 16th-century Gasparo da Salò viola is etched, there are two rooms joined by an arched opening—the architecture reminiscent of an old-world library. The handcrafted butternut woodwork complements the green panels of the coffered ceilings, its soft glow also warming the wainscoting and cabinets, inlaid with thick, bubbled antique German glass.

Viola clefs and primrose blossoms appear throughout the rooms, repeated motifs carved in wood or engraved in metal escutcheons. Such careful detail reveals that the archive’s namesake was clearly revered.

According to Claudine Pinnell Bigelow, ’92, BYU assistant professor of viola, “Dalton paid attention to every detail that would truly honor this great artist. Dalton had a vision for the rooms and raised the money. The work he has created is something that violists will look to for generations.”

Upon entering, one first sees the Primrose Room, an exhibition space where displays celebrate the accomplishments of William Primrose. The boxes of letters and photograph albums motivate and inspire, Bigelow says. “You can’t hold a letter from Béla Bartók in your hands and see this correspondence between major artists of our time and not be touched by that and recognize its value.”

On the wall hangs Primrose’s pedagogical genealogy, tracing his teachers and his teachers’ teachers through time. It reads like a who’s who of musical history and extends back to violinist and composer Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713).

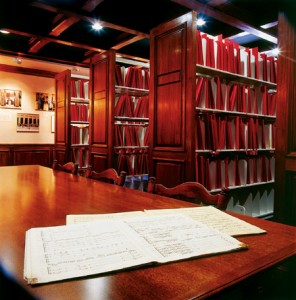

While the Primrose Room shares the history of great artists, the adjoining room—the PIVA—puts today’s violists to work, offering access to a remarkably comprehensive resource. Scores of scores line four long shelves—thousands of printed pieces of viola music with a distinctive cream-colored cover and red binding.

Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94

Behind the shelves are three study carrels with computers. Many of Primrose’s recordings (on CDs) can be borrowed from music special collections or experienced in audio and video on the Internet at viola.byu.edu.

Those unable to travel to Provo can also benefit from the massive printed collection. “We have this wonderful resource of printed viola music that goes out through inter-library loan on a regular basis and can be an incredible resource for the international viola community,” says Bigelow.

Primrose-Colored Classes

Honoring Primrose at BYU goes beyond the beautifully appointed rooms and expansive collection. Every March, BYU sponsors the William Primrose Memorial Concert and ViolaFest. Dalton explains, “The concert is an event that we have had since Primrose’s death in 1982. Eminent violists give a concert here, give master classes, and perform with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.”

The Primrose room provides violists worldwide with thousands of scores as well as access to letters and photographs celebrating the accomplishments of William Primrose. For BYU students and faculty, the room is a valuable resource for teaching and learning. Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94.

In 2003 the Saturday master classes followed a Friday-night concert by Helen S. Callus, assistant professor of viola at the University of Washington and president-elect of the American Viola Society. Bigelow says the program had significant effect on her students. “For this class to come on the tail end of a beautifully played recital opened their hearts and their minds to receive critiques in the best possible way and to feel committed to making the changes that she asked them to make. They always play 10 times better after this concert.”

Students also benefit from the collection itself. One of Bigelow’s students, Leslie Jean Richards, ’04, is cataloguing Primrose’s original manuscripts so they are searchable online. Her familiarity with the archive allows her maximum benefit from the collection. “It is extremely helpful when I want to look at other editions of a piece I’m studying,” Richards says. “Additions to the archive come in steadily and always include some of the newest, and also hardest to find, viola pieces from around the world.”

Richards says the internationally known collection enhances BYU’s reputation. “In meeting violists from around the country, I mention that I’m from BYU and the first thing they ask about is the Primrose Archive.”

Resonating Influence

Photo courtesy Harold B. Lee Library

The PIVA lies at the top of well-worn stairs and tucked down an unremarkable hallway. But classical music lovers and violists everywhere are learning where to go if they want to immerse themselves in the world of the viola.

Oberlin College professor Peter J. Slowik, a former president of the American Viola Society, says, “My recent visit to PIVA was a fascinating and inspiring journey through the history of the instrument. Whatever your interest—discovering new repertoire, getting to know the viola’s legendary performers through their memorabilia, or enjoying brilliant recorded performances—it’s all here, in one convenient center.”

And in this room that honors great artists and teachers throughout history, the business of teaching continues.

“When I need some type of interesting piece that will really connect with a student—a piece of music that will really connect with their heart but also develop their technique and help them stay motivated—I come to this room and look for something unusual,” says Bigelow, who has succeeded Dalton as manager of the archive.

Photo by Bradley H. Slade, ’94

With this rare resource comes the opportunity for viola students and teachers—a peculiar group that has chosen a less-popular musical path—to tuck a bit of history under their chins, draw a bow across the strings, and discover a harmony within themselves. Several of Primrose’s violas are prominently presented in a glass case. But they are not just for display. “I come here sometimes to play on the instruments,” says Bigelow. “They need that, for good health. They need to be resonating, they need to be ringing. And that is, I think, what this place in turn does for me. It helps my mind and my heart and my spirit to resonate.”

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.