The 20th century has become the most violent century in human history We have killed more people in this century than we have killed in any of the past centuries. And by the indications, we continue to kill more and more people and destroy more and more human lives all over the world. It makes one wonder, What is going to happen to us in the 21st century?

I am reminded of a question that a Western correspondent asked Grandfather in 1945 after the atom bomb was thrown on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The reporter asked, “What is the future of humankind?” Grandfather’s response was: “Up to now we had the option of choosing between violence and nonviolence. Now the only options left to us are nonviolence and nonexistence.”

Although he said this in terms of the nuclear threat that he perceived at that moment, he also said it in terms of the spiritual threat that affected all of us. It’s not just the wars that we need to be concerned about. Our loss of humanity is also a matter of great concern. We are becoming so immune to violence that we don’t care what happens to people, and this kind of a spiritual death is more dangerous than all the violence we see around us.

We don’t want to make the 21st century more violent than the 20th century. We want to reverse the course and make it less violent so we can all live in peace and harmony. And we can do this. We can achieve peace if we are determined to make the effort. But if we continue to flow with the tide and say that we can’t do anything about it, and whatever we do is not going to make much of an impact anyway, then we are just going to face the situation that we come across and live with it and perish with it.

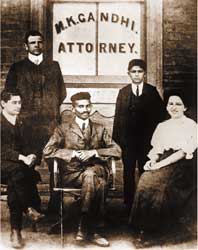

But each person can make a difference. This has been shown to us in the way Grandfather got up and made a difference when he was faced with humiliation. He didn’t intend to become a great person. When he came back from England with a degree in law, his only intention was to set up a legal practice and earn money so that he could pay back the loans the family had taken for his education. He was desperately trying to set up legal practice in India, but for some reason he failed miserably for two years. Then he got an opportunity to go to South Africa to interpret between an Indian merchant and his white British lawyer. He was to go as an interpreter, not a lawyer, but he was so desperate that he grabbed the opportunity.

Ironically, if it hadn’t been for racism and prejudice, we may not have had a Gandhi. I wouldn’t be here standing and talking to you about my grandfather. He may have been just another successful lawyer who had made a lot of money. But because of prejudice in South Africa, he was subjected to humiliation within a week of his arrival. He was thrown off a train because of the color of his skin, and it humiliated him so much that he sat on the platform of the station all night wondering what could he do to gain justice.

His first response was one of anger. He was so angry that he wanted eye-for-an-eye justice. He wanted to respond violently to the people who humiliated him. But he stopped himself and said, “That’s not right.” It was not going to get him justice. It might have made him feel good for the moment, but it wasn’t going to get him any justice.

The second response was to go back to India and live among his own people in dignity. He ruled that out also. He said, “You can’t run away from problems. You’ve got to stay and face the problems.” And that’s when the third response dawned on him–the response of nonviolent action. From that point onwards, he developed the philosophy of nonviolence and practiced it in his life as well as in his search for justice in South Africa. He ended up staying in that country for 22 years, and then he went and led the movement in India.

Had it not been for that one moment when he was humiliated, he would not have made that change in his life. All of us face these moments in our lives, but often we don’t make the right choices. We submit to anger, and in our search for eye-for-an-eye justice, we increase the level of violence in our societies. But we can make the right choice if we learn how to deal with anger positively.

This is an aspect of Grandfather’s philosophy that not many people have focused on. People have focused on the part of his philosophy that deals with reacting to an injustice, and we think that is the whole philosophy, that whenever you see an injustice taking place, you react to that situation in the best way you can, as peacefully as you can. But there is a proactive part of his philosophy as well, and that is, How do we avoid conflict? It’s one thing to learn how to resolve conflicts peacefully, but it’s quite another to learn how to avoid conflicts altogether.

If we look at ourselves and examine our lives, we will find that many of the conflicts emerge from two main sources. One is our inability to deal with anger positively, and the other is our inability to build good relationships, meaningful relationships. If we could learn these two things, we would be able to reduce violence in human society by as much as 90 percent.

Are we so ashamed of anger that we don’t even want to talk about it, let alone teach it? We just tell people that it’s bad to keep anger pent up inside: “You’ve got to get it out of your system. Find your own way of doing it–punch a pillow or go out into the woods and yell at the trees–but get it out of the system. That’s the important thing.” But that is not important. Getting it out of the system may momentarily bring peace to you, but if you don’t address the problem, it’s going to come back again and again until you give up and respond in anger. It’s essential that we learn how to deal with anger positively.

Grandfather taught me this very powerful lesson when I came to him as a 12-year-old boy. I lived in South Africa and suffered the same kind of humiliation that Grandfather had suffered, but at a very young age. I was 10 years old when I was beaten up by some white youths one day in the street. A few months later I was beaten up by some black youths. For the whites I was too black, and for the blacks I was too white. I was filled with anger and rage, and I wanted eye-for-an-eye justice because that’s what I knew. It became such an obsession with me that I subscribed to Charles Atlas’ exercise programs to pump iron so that I could deal with all these people. And that’s when my parents decided it was time to take me to India and give me the opportunity to learn something from Grandfather.

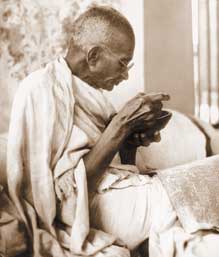

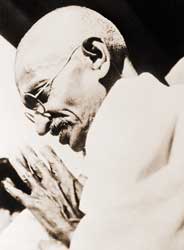

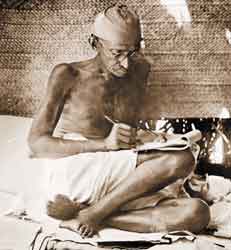

Gandhi was the dominant figure of the Indian Nationalist movement from 1920 until India gained independence in 1947.

I’m very grateful to my parents for that decision because I think in many ways the 18 months that I spent with Grandfather laid the foundations for my understanding of his philosophy. One of the first lessons he taught me was how to deal with anger. He told me that anger is like electricity. It’s just as powerful and just as useful as electricity, but only if we use it intelligently and with respect. If we abuse electricity we can destroy ourselves and everything around us. And just as we channel electricity and use it for good, we must be able to channel anger and use it for the good of humanity.

He suggested that I write an anger journal–but with the intention of finding a solution, not with the intention of keeping the anger alive. A lot of people have told me over the years that they’ve been writing anger journals, but it hasn’t helped them because every time they read the journal, they feel a renewal of the anger. I tell them, “Try writing it with the intention of finding a solution, and then commit yourself to finding a solution.” And that’s very important. If we commit ourselves to finding a solution, we’ll be able to find a solution and put the whole episode behind us. I did that for many years, and I’ve been able to channel my anger very substantially into constructive ways of dealing with situations. I think in many ways the reason I am here and am doing the type of work I’m doing is because I’ve been able to channel anger to help people understand and improve their lives.

Now, I was a feisty young boy at that time, and I wanted to see whether Grandfather had learned the lesson he was trying to teach me. I decided to test him. This was the time when he was in the midst of high-level political discussions. Britain had already decided to give India independence. Negotiations were going on regarding how to transfer power to Indian leaders.

All of these important things were happening, and along with that he was also concerned about the emancipation of women, about the emancipation of the so-called untouchable people in India, and about the education of children. He had all of these programs going on simultaneously. To raise funds for all these programs he decided to sell his autographs, so he put a fee of $5 for each autograph. Every morning and evening after his prayer services, when people would gather for his autograph, it was my duty to go out into the audience and pick up their autograph books and the money and bring it to him for his signature. One day I thought, If everybody can get his autograph, why not me? And so I got myself an autograph book, and I slipped it into the pile and hoped he wouldn’t notice the absence of money there. But he was very shrewd. When he came to my autograph book, he said, “Why is there no money for this autograph?”

I said, “Because it’s my book.”

And he said, “Well you should know that I don’t make an exception, even for grandsons. If you want an autograph, you will not only have to pay me for it, but you’ll have to earn the money and pay me.”

I said, “No way. You are my grandfather, and I’m going to make you give me this autograph free.”

And he laughed and said, “All right, let’s see who wins.”

From that day, every day when he was in the midst of these high-level political discussions with British politicians and Indian politicians, I would barge into the room with my autograph book and thrust it in his face and demand an autograph. My logic was that just to get rid of me he would sign the book. But instead, every time I became too boisterous, all he did was put his hands across my mouth, press my head against his chest, and go on talking politics.

On many occasions some of the other politicians would get exasperated and tell Grandfather, “Why don’t you give him the autograph and be done with it? He comes and disturbs our meetings every day.” Grandfather would only laugh and say, “No, this is our private joke. You don’t have to get involved in it.”

Well, the long and short of it is that he never did give me that autograph. But I don’t remember his ever telling me to get out of the room and leave him alone, like some of us do with our children when they come into the room while we are working on something important. We shoo them away and say, “Get out,” “Leave me alone,” “We’ll talk about it later”–all that kind of thing. But he never ever did that. That’s when I realized that he had really, very substantially, taken control of his anger.

I had an occasion to put this to test in another way much later. In 1968 I was living in India, a victim of Apartheid because the South African government wouldn’t allow me to bring my Indian-born wife to South Africa. And in 1968 a friend of mine from South Africa was coming to India for the first time. He was very nervous about making this trip, so he wrote to me to come and receive him at the docks and to make arrangements for his stay in India. His ship arrived at 10 o’clock in the night, and I was the first Indian to go on board. But instead of meeting my friend, I met a strange white man, who came up to me and grabbed hold of my hand and shook it profusely and introduced himself as a member of parliament from South Africa. The moment he told me his name, I recognized who he was. He was an extremely racist person. He was responsible for the Apartheid policy because he supported his party’s policy. To me he was responsible for all the humiliation I felt.

In that moment all the experiences in South Africa flashed through my mind, and that anger came up, and I wanted to humiliate him and tell him, “Go and jump into the sea. I’m not going to do anything for you.” But I stopped myself immediately and said, “What would Grandfather say if I did that?” And I knew that not only would he not forgive me, but even my parents would not forgive me. And so I changed. I shook hands with him and I said, “I’m glad to meet you. I am a victim of Apartheid, having to live in this country because your government won’t allow me to bring my Indian-born wife there. But I’m not going to hold that against you. You are a guest, and I’m going to try to make your stay here as pleasant as possible.”

They were in Bombay for about five days, and every day from early in the morning to late in the night, we would be together. We did everything together–from eating breakfast to doing all the touristy things and shopping and all of that. From time to time I would question him and try to find out how he could justify Apartheid. He would make a valiant attempt to justify it to me. Every time the discussion became a little uneasy, we would change the topic and talk about the weather. On the fifth day, when my wife and I said final farewells to them, both of them embraced us and literally wept tears of remorse. They were genuinely crying, and they asked us for forgiveness. They said, “In this short time you have opened our eyes, and you made us understand how evil Apartheid and prejudice is. And we are making a promise to you that we are going to go back to South Africa and fight Apartheid.”

I was a skeptic, so I told my wife quietly, “Let’s wait and see. These people have a habit of coming out and saying one thing and going back and doing something else altogether. Let’s wait and see whether he really meant it or he was just saying it to make us feel nice.”

We followed his political career for the next seven or eight years, and we realized that he had changed. He had changed to such an extent that he was eventually thrown out of his party and lost his elections, but he remained firm in his conviction that Apartheid was evil. That was the change we were able to bring about in a confirmed racist in just five days of simple dialogue, of friendly discussion. And that’s when I realized the power of nonviolence. It is very effective if we learn how to use it properly.

But we are often so focused on the physical violence that we don’t look at the passive violence we do against people. This was a very important lesson I learned from Grandfather when he taught me to make a family tree of violence in the same way as we build a genealogical tree. He said, “Every day before you go to bed, put down on that tree all the experiences of violence that you’ve had during the day, things that you may have read or seen or observed or even perpetrated against other people. You have to be honest and put all of that down on that tree.

“Violence,” he said, “is the grandparent, with physical violence and passive violence as the two offspring.”

Passive can be either conscious or unconscious. We don’t use any physical force, but our body language, our attitudes, the way we speak to people, the way we look at people, the things that we do and say to people–all of these can be acts of violence. Actually, it is the passive violence we commit all the time–knowingly or unknowingly–that generates anger in the victim, and that anger then translates into physical violence. In effect, passive violence fuels the fire of physical violence.

If we want to put out the fire of physical violence, logically we have to cut off the fuel supply. And the fuel supply is us–each one of us. We have to look at our own selves and acknowledge that we are violent and need to change. The exercise that Grandfather made me do was a way of learning about my own violence and acknowledging it. I’m sure if I ask all of you now whether you are violent or nonviolent, you will all be willing to swear on the Bible that you are nonviolent. But we are nonviolent only in the sense that we don’t go out and beat up people or kill people. But we are violent in the sense that we practice a lot of passive violence, and unless we acknowledge and change that, we’ll never be able to create a peaceful society. It’s a very important lesson for us to learn.

I learned another very important lesson from Grandfather over a little pencil–a little three-inch stub of a pencil became the object of a major lesson for me. When I was coming back from my tuitions one day–I was 13 years old then, and you know how careless 13-year-olds are–I had this pencil in my hand and a notebook, and I looked at the pencil and I said, “I deserve a better pencil. This is too small for me to use.” So I threw it away.

That evening when I met Grandfather, I asked him for a new pencil. But instead of giving me a new pencil, he subjected me to a lot of questions. He wanted to know how the pencil became small and why did it become small and where did I throw it away and on and on and on. I couldn’t understand why he was making such a fuss over a little pencil until he told me to go out and look for it. I said, “You must be kidding. You don’t expect me to look for this little pencil in the dark.”

He said, “Oh yes, I do. Here’s a flashlight. This will help you.” And he sent me out with a flashlight to look for this pencil.

I think I searched the bushes for about three hours. When I finally found the pencil and brought it to him, he said, “Now I want you to sit here and learn two very important lessons. The first lesson is that even in the making of a simple thing like a pencil, we use a lot of the world’s natural resources. When we throw them away, we are throwing away the world’s natural resources, and that is violence against nature. The second lesson is that because in an affluent society we can afford to buy all of these things in bulk, we overconsume these things, and because we overconsume the resources of the world, we are denying those resources to people elsewhere who have to live in poverty. And that is violence against humanity.”

That was the first time I realized how wide and broad his philosophy of nonviolence was, that every little thing we do every day–throwing away things or wasting things or destroying things–are acts of violence. We do this all the time. I’ve been living on university campuses for 12 years in the United States, and I’ve never had to buy a pen or a pencil because I find them lying all over the campus. I’m constantly picking up these pens and pencils and using them. Many of the students who’ve seen me doing this think I’m a crank, and they come running to me and say, “Mr. Gandhi, here’s a pencil we found for you.” I hope that someday they will learn the profound lesson I learned.

But I have to come to an end now, and I want to share two last stories to show you how we can build relationships between people, which is so very important.

We have to live what we want our children to learn. There was a little boy, six years old, who was living in the community that Grandfather had created–the same community in which I was living with him when we were visiting India. This boy and I were very good friends, and he had a very strong sweet tooth. He just couldn’t resist sweets, and the result was that he started getting boils all over his body. When his parents took him to the doctor, the doctor said, “You’ve got to stop him from eating sweets–no more sweets until he is cured of this ailment.”

So the parents would nag the boy every day, “You are not going to get sweets anymore. The doctor has said no sweets for you.” Yet there were sweets on the table, and everybody else was eating sweets. The result was that this boy didn’t obey his parents. When nobody was looking, he would grab some of the sweets and eat them. The result was also that he couldn’t be cured.

After a few days, the mother came with him to Grandfather and said, “Would you please explain to this boy that he is not to eat sweets? We have been trying to tell him this for several days, but he won’t listen to us. Now I want you to speak to him.”

Grandfather said, “All right, you come back after 15 days and I will speak to him.” The mother came back after 15 days and Grandfather took this boy aside, spoke to him for less than half a minute, and the boy went home and gave up sweets. He wouldn’t touch sweets anymore.

The mother was puzzled. She came back to Grandfather and asked him, “What kind of miracle did you perform? We were telling him to do the same thing, and he wouldn’t listen to us. Yet you spoke to him for half a minute, and he has obeyed you.”

Grandfather said, “It wasn’t a miracle. The only thing I told him was, ‘I’ve given up eating sweets for 15 days, and I’m not going to eat sweets until you are allowed to eat sweets. And I hope that you will give them up too.'” The parents were not doing this. They were merely using their parental authority to tell that child not to do something that the doctor said not to do. And so the child didn’t obey them. We have to set an example through our own lives.

The last story that I want to share with you happened to me when I was 16 years old. We were back in South Africa and living on the Phoenix Ashram that Grandfather had created, which was 18 miles outside the city of Durban in the midst of sugarcane plantations. Our nearest neighbors were two miles away from us. Any time my two sisters and I got an opportunity to go to town and visit friends or see a movie, we would grab the chance and go. One Saturday my father had to go to town to attend a conference, and he didn’t feel like driving, so he asked me if I would drive him into town and bring him back in the evening. I jumped at the opportunity. Since I was going into town, my mom gave me a list of groceries she needed, and on the way into town, my dad told me that there were many small chores that had been pending for a long time, like getting the car serviced and the oil changed.

When I left my father at the conference venue, he said, “At 5 o’clock in the evening, I will wait for you outside this auditorium. Come here and pick me up, and we’ll go home together.”

I said, “Fine.” I rushed off and I did all my chores as quickly as possible–I bought the groceries, I left the car in the garage with instructions to do whatever was necessary–and I went straight to the nearest movie theater. In those days, being a 16-year-old, I was extremely interested in cowboy movies. John Wayne used to be my favorite actor, and I got so engrossed in a John Wayne double feature that I didn’t realize the passage of time. The movie ended at 5:30, and I came out and ran to the garage and rushed to where Dad was waiting for me. It was almost 6 o’clock when I reached there, and he was anxious and pacing up and down wondering what had happened to me. The first question he asked me was, “Why are you late?”

Instead of telling him the truth, I lied to him, and I said, “The car wasn’t ready; I had to wait for the car,” not realizing that he had already called the garage.

When he caught me in the lie, he said, “There’s something wrong in the way I brought you up that didn’t give you the confidence to tell me the truth, that made you feel you had to lie to me. I’ve got to find out where I went wrong with you, and to do that,” he said, “I’m going to walk home–18 miles. I’m not coming with you in the car.” There was absolutely nothing I could do to make him change his mind.

It was after 6 o’clock in the evening when he started walking. Much of those 18 miles were through sugarcane plantations–dirt roads, no lights, it was late in the night–and I couldn’t leave him and go away. For five and a half hours I crawled along in the car behind Father, watching him go through all this pain and agony for a stupid lie. I decided there and then that I was never going to lie again.

I think of that episode often. It’s almost 50 years since the event, and every time I talk about it or think about it I still get goose bumps. Now, that is the power of nonviolent action. It’s a lasting thing. It’s a change we bring through love, not a change we bring through fear. Anything that is brought by fear doesn’t last. But anything that is done by love lasts forever.

I’d like you to remember this because as we come into the 21st century, you are the future leaders of the world. My generation has made a mess of this world, but your generation doesn’t have to live with it. You can make a difference. I hope you will make the right choices and make that difference so the 21st century can be more a peaceful century than the 20th was.

This article is adapted from a BYU forum address given Mar. 23, 1999, in the Marriott Center. The text of this article is copyrighted by Arun Gandhi. For information about Mr. Gandhi, contact Westvale Talent at 1-800-785-8498.