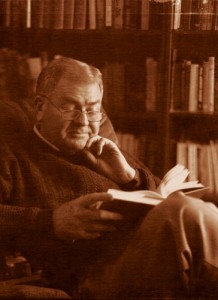

A bookworm of the highest order, Stephen Tanner has spent a lifetime culling meaning from literary works.

The temptation was too great: Long shelves of paperback books. An open bookstore. A short walk from the church building.

Lured by the promise of literary adventures in philosophy, religion, and history, Stephen L. Tanner skipped Sunday School.

Now a BYU English professor and the university’s 2004 Karl G. Maeser Distinguished Faculty Lecturer, as a teenager in the 1950s, Tanner was captivated by those paperback volumes, sitting neatly on the shelves of a long, narrow shop on Washington Boulevard in Ogden, Utah.

The store’s single aisle beckoned with the song of page-turning Sirens, and in it he discovered Homer, Emerson, and Hemingway. As the boy browsed the book covers, he mentally grazed on the ideas of the great minds of history as they grappled with timeless moral issues—the joys and sadnesses, the ideals and inequities of human experience.

This Sunday School truant would grow up to embody twin ironies. First, he became the type of engaging teacher who just might have kept him in those church classes five decades ago. And the reformed sluffer became a champion of studying morality in the written word, making him anything but trendy in the latter stages of his career. Instead, he has thrown himself into the conflict about what our reading can or should mean to us, and he is an unpopular voice for finding Truth—capital T, please—in literature.

World-Class Browsing

Tanner, unsurprisingly, is a bookworm. But he’s a bookworm the way Godzilla was a nuisance. In the otherwise unfinished basement of his home, Tanner has an office with a desk, a computer, a file cabinet, walls of books, and a blue recliner. A stereo rests on a shelf, from which revered melodies emanate, surrounding Tanner while he reads. “I grew up with classical music wafting through the vents from his basement office,” says daughter Charlotte Tanner Poulton, ’89.

What’s remarkable, though, is neither the music nor the recliner, nor the books piled around it. The peculiarity here is the number of books—on the floor and the shelves—with bookmarks inside.

“I have a strange habit of starting many books and having them going at the same time,” he says. “I complete some many years later. I have hundreds with bookmarks in them.” On any given day Tanner could be in the process of reading more than a hundred books—and not just in English. He taught himself German and Portuguese and regularly devours books in those languages.

This is not indicative of an inability to finish what he starts; Tanner completes several books each week. This is world-class browsing, born in that single-aisle bookshop on Washington Boulevard and repeated at libraries and bookstores around the world.

Used bookstores, in particular, are riptides pulling him in and under—garage sales, too, but he is beginning to win on that front.

“I’m trying to wean myself,” Tanner says of stopping to hunt for book treasure at yard sales. He adds wryly, “I’m at the point where I have to sit down and calculate how many hours are left to me and how many pages I read an hour; I have to be realistic with myself. It’s a moral victory if I walk away from a book sale empty-handed—I’ve exercised a certain kind of self-discipline.”

Over the years, libraries at various universities honed his browsing skills. In addition to taking research expeditions to other schools’ book repositories, he received degrees at the University of Utah and the University of Wisconsin and taught at the University of Idaho before coming to BYU in 1978.

“I wrote my doctoral dissertation in a carrel at the University of Wisconsin library,” he says. “Going from and coming to my carrel and during rest breaks I naturally browsed through the stacks and found all kinds of remarkable things, such as bound volumes of 1940s radio programs. The Jack Benny Show was there—the entire script, with the Pepsodent ads.

“These were the kinds of books you couldn’t find in bookstores, especially today when bookstores are full of only marketable stuff. Part of the fun as a reader is making such discoveries. Browsing is a matter of serendipity, stumbling upon exactly what stimulates you but which you’d never have found without stumbling upon it by accident.

“It’s like gold prospecting.”

Among the literary gold Tanner has prospected is a wide variety of authors—he doesn’t confine himself to a highbrow canon of books. One of his favorites is John Buchan, a Scottish writer and pioneer of mystery-adventure novels. Buchan was a primary influence on Sir Ian Fleming, creator of the James Bond books and movies. He also enjoys Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Rex Stout’s “Nero Wolfe” novels, and Josephine Tey mysteries. Clearly, he prefers the mid-20th-century detective formula.

“The contemporary ones tend to focus on the violent and sordid, and the heroes are more fallible and problematic and psychologically screwed up,” he laments. “I like the brilliant mind solving a puzzle. There’s still room for conventional heroes, even though they’re not realistic. I don’t need to know the detective is having all kinds of marital troubles.

“The pleasure in popular fiction is often the simplified version. We all know when the crime is solved it then goes out into the courts and often the criminal gets off. But we all like to see good triumph over evil, order brought out of chaos.”

As such comments suggest, even in his recreational reading, Tanner never gets far from his literary approach, one that searches for truth and takes morality seriously.

Searching Broadly For Truth

During his service in the Northern States Mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Tanner determined his interests lay in “the area of the humanities, where history, philosophy, and religion impinge on literature.”

Holding to this creed, Tanner has crossed swords with much of his field for 40-odd years. The literary critic, raised on paperback classics, embraced a broad education—call it generalization—just as literary, technological, and academic trends began to push out the generalist and emphasize the specialist.

For a boy in the 1950s, “it was quite natural for a young person to aspire to read great books,” he says. “Now in high school they focus on what is popular, timely, trendy. I was raised with an ideal—and it still seems a meaningful one—to try, in Matthew Arnold’s terms, to know the best that’s been thought and written. I’m a little concerned that the notion of coverage—trying to learn a little bit about all the major periods of literature—is being lost because we live in an era of specialization. It’s very difficult for anyone to be a generalist.”

While the best literature programs in higher education, including BYU’s, still stress breadth and coverage, the increasing number of colleges, students, and professors has allowed and necessitated academic research in literature to proliferate. In addition, the sheer number of books and authors makes true breadth difficult to achieve.

“There is so much specialization and so much written, period,” Tanner notes, “that it’s hard for one person to get a handle on all of western literature.”

Tanner chose to write biographies of two literary critics who subscribed to broad moral criticism, Lionel Trilling and Paul Elmer More. “I tend to still see value in a man of letters who has a broad background in literature and ideas,” Tanner says, speaking of others but simultaneously describing himself. “Trilling and More were both generalists, men of very broad and wide-ranging knowledge, so when they’d talk about a particular writer, they could do so knowing about the history of literature and the culture in which the particular work was written. I still like people who can attempt that.”

Tanner believes universities no longer train students in the same fashion and expects literary generalists to become increasingly rare. If so, Tanner is himself a bridge to a bygone epoch.

“Professor Tanner is a generalist, a devoted and well-read student of literature, philosophy, religion, and the arts,” says emeritus BYU English professor Richard H. Cracroft, ’63. “He is not merely dabbling when he addresses so many subjects; instead, he is bringing a consistent moral temperament and broad humane knowledge to bear on a diverse variety of individual subjects. Whatever the topic, his writing bears the stamp of a distinct set of attitudes and values derived from passing an expansive study of the humanities through the alembic of his religious faith.”

Tanner’s combination of literature, philosophy, and religion put him at odds with many in his field. He has adopted a moral-philosophical approach in a time when contemporary literary theory holds that, as Tanner says, “there is no reading, only misreading. There’s no Truth to be discovered.” Tanner attacks those theories as stripping literature of important meaning.

“Ideas have consequences, and literary ideas have consequences,” Tanner says. “Literature is not simply part of an aesthetic dimension where we go just for escape and pleasure. The writer teaches whether he intends to teach or not. In fact, I feel we are most often influenced by literature that appears to be merely entertainment. I’ve always felt you can’t separate literature from life and you can’t separate life from large moral concerns.”

There is antagonism aimed at his position. One book editor wrote a note to Tanner saying that Tanner’s text widened the understanding of his subject, but there was “just a trace of bourgeois priggishness in some of your judgments.”

Cracroft defends Tanner’s approach: “Every critical study should entail some element of moral evaluation, which nowadays is often considered ‘bourgeois priggishness.’”

Tanner fired one of his broadsides against this trend in a 1999 article in Humanitas, a humanities journal: “So long as literary academics disregard the relation of literature to life and remain isolated from the general culture . . . , they lack the kind of confrontation with reality essential to debates about how society ought to function. . . . Literary study used to be a repertoire of often compatible approaches (formalistic, biographical, psychological, philological, archetypal, moral, etc.). These approaches shared the fundamental assumption that authors are human beings capable, within broad linguistic possibilities, of describing and interpreting in meaningful ways to others the intellectual, emotional, and spiritual range of human experience.”

Solitude and Stimulation

If Tanner’s life has been devoted to learning from the range of human experience, he hasn’t been afraid to take that search within himself. In fact, he cherishes opportunities for solitude and introspection.

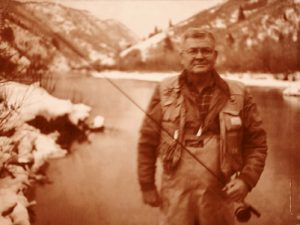

He loves fly-fishing, especially tying flies, and recently he wrote an essay about Ernest Hemingway and Zane Grey and their love of the sport.

“With both fishing and fly-tying, people have the idea they are times of reflection,” Tanner says. “They are not. They are times of total occupation of your mind with the task at hand: selecting the right fly, making the right cast. That total absorption can be a pleasant contrast to hectic work.”

But time for reflection was a part of a family cabin on the Provo River, where for 30 years Tanner enjoyed solitude and practiced catch-and-release fishing—”I was almost on a first-name basis with the trout in the area,” he says. “I could also go up there if I wanted to do a little writing and could combine writing in the peace and tranquility with some fishing.”

Solitude is a quality in short supply today, Tanner believes. His experience as a professor bears out his opinion.

“Some people can’t bear to be alone with themselves,” he says. “Young people need to be plugged into their headphones. They are like an oxygen tank. They can remove them for a short time but then need to be back on them. And as much as they learn from video games—and they may very well teach good reflexes—they don’t teach reflection.”

In fact, he says, what now passes as reflection “is insipid mental screen saving.”

“There is a blurred distinction between loneliness and solitude,” he adds. “Loneliness can be a terrible thing, but solitude is what we’re on the earth for. Ultimately, we are born alone and we are alone in our inner consciences in our life and we need to be comfortable with that. The craving for stimulation and the flight from solitude is an escape from what should be a healthy, adjusted life.”

Even university students struggle to maintain interest, Tanner says. “A generation that is entertained almost to excess carries the expectation for entertainment into the classroom, so they tend to be passive spectators unless teachers are able to engage or involve them.”

Tanner’s quest to engage students has led him from a distinguished teaching honor at the University of Wisconsin, where he did graduate work, to similar awards at BYU, including the Maeser Lectureship. He also participated in the Center for the Improvement of Teacher Education and Schooling at BYU’s David O. McKay School of Education. But he rededicated himself to transforming his methods after one particular experiment.

In his experiment, Tanner required his students to read Edgar Allen Poe’s “Ligeia,” a story rich in descriptive adjectives. “Poe was aiming for effect, and that effect had to be created by stimulating pictures in the reader’s imagination.”

But when Tanner questioned the students about the setting, many couldn’t remember anything about it. “They were looking ahead to movement in the plot,” he says, explaining that what is lost is a bridge between the reader and the experience of the book.

“Reading can enrich by providing experiences,” Tanner says. “And if it’s sensitive reading, it’s almost as if you had been there and had that experience. That’s very important because our lives are very limited in what we can do.”

He also bemoans the loss of ability to create mental images from a text. “We live in such a visual age,” he says. “The evocative fictional images don’t register for students who are overstimulated by television and film.”

To engage overstimulated students, then, Tanner relies on classroom discussion, although he calls the tool both the best and the most dangerous. “The worst thing a teacher can do is ask a question with an answer in mind and take hands until he finds that idea or answer. Good students will recognize very soon when the teacher is playing that guessing game and bright students will remove themselves from the discussion.”

Also, “discussion is very popular with students but highly overrated because it is often a time filler, and students leave without any sense of closure. Sometimes they feel it’s been stimulating because a lot of people have talked, but lots of times they’ve just been talking past each other.”

Instead, Tanner tries to present facts, lay out an issue, and then act as a gardener.

“Conducting a discussion is a very difficult skill. It’s like planting a seed with the idea. You have to do some weeding when tangential comments arise and maybe some watering and fertilizing by rephrasing the question or recognizing useful comments. A teacher needs to coach students so they respond to each other and they present some persuasion and evidence for their comments.”

The Disciplined Life

Throughout his career, Tanner has rigorously maintained his focus, leading to significant recognition, locally, nationally, and internationally. He has been honored with the Lionel Trilling Award, which recognizes scholars whose work has broad intellectual and moral implications, and has received four Fulbright Senior Lectureships, one to Portugal and three to Brazil. The discipline that has helped him achieve such honors is evident in his approach to writing.

“I’m a very slow, deliberate writer,” he says. “I grind sentence by sentence. It’s very painful. Sometimes writing involves an hour, two hours on a paragraph.”

However, when he is done, he is just that; the work requires very little editing. Wrote one editor: “The editing is very light because you have written well and carefully (surprise, surprise! this is such a novelty these days!).”

It is a talent he has applied to a dizzying array of essays and articles on subjects as diverse as James Thurber and Sinclair Lewis, trout fishing and war metaphors, spiritual values in the popular western and similes in novels by Raymond Chandler, the humor of E.B. White and gender conflict. He has written four books plus nearly 200 chapters, articles, papers, and reviews.

To do his work, he purchased an Olympia manual portable typewriter in 1958 while on his mission in Michigan. He still uses it occasionally, but it once was his trusted companion. Years ago, Tanner climbed into the passenger seat of a friend’s car for a long drive to a favorite fishing spot in Montana. Tanner surprised his fishing buddy by pulling out his Olympia typewriter and setting it on his lap; a deadline loomed. He pecked away for hours, with intermittent long stares out the window.

He remains distrustful of the desktop computer in his office in the Jesse Knight Humanities Building because using a word processor makes it too easy to move around paragraphs and chunks of text, something that feels, given his painstaking style, too undisciplined.

Despite his disciplined writing and his tenacious fight for morality in literature, Tanner has a relaxed, almost quirky side. He collects pocketknives—each of his grandchildren has received at least one as a gift—and is a font of folk songs.

He recently stunned and delighted a German audience with a number of cowboy songs at a conference on literature of the American West. Tanner was in Germany lecturing about Ernest J. Haycox, a writer of Westerns about whom Tanner has written what many consider to be the definitive biography. One evening, by pseudo campfire, Tanner sang an hour’s worth of songs, including “The Streets of Laredo.”

“The Germans got a big kick out of that,” says Tanner, who has also entranced study-abroad students with Scottish folk songs. “I came from a fraternity background, where singing was important, and also a folk-song era. Somehow I accumulated dozens of folk songs. I found once that I could drive hundreds of miles, a six-hour trip, and sing the whole time without repeating the same songs.”

From folk songs to detective novels to fly fishing to literary classics, Tanner is clearly a man of broad interests. But at his core he is still that teenager in Ogden who loves to slip away and read a good book. Passing on that love of reading to students, children, and grandchildren has been a quest that has come naturally.

Tanner’s daughter Elizabeth Tanner, ’88, says his grandchildren now enjoy his storytelling, just as his three children fondly remember lying curled up on their parents’ bed as their father read to them. “I remember,” she says of her childhood, “after Sunday dinner we’d all retreat to a couch or a chair with books.”

Tad Walch is the Utah County Bureau chief for the Deseret Morning News.

FEEDBACK: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

As the 2004 Karl G. Maeser Lecturer, on Oct. 26 Stephen Tanner delivered a BYU forum address titled “What Are You Thinking?” The subject of his address was solitude and reflection. To read the full text, go to more.byu.edu/stephentanner.

What Are You Thinking?

By Stephen L. Tanner

In reviewing my title after it was announced, I realized that it could mean different things depending on which word is emphasized: What are you thinking? meaning, What exactly is going on in you head? What are you thinking? meaning, If I have misunderstood you, exactly what did you mean? What are you thinking? meaning, I’ve told you what I think; now give me your ideas. What are you thinking? meaning, You couldn’t have been thinking at all. Perhaps what I am going to say touches upon more than one of these meanings.

Have you ever stopped to consider how many synonyms we have for the words think, thinking, and thought? Some are part of our active vocabulary and are familiar friends—words like ponder, muse, reflect, reason, meditate, contemplate. Some are part of our recognition vocabulary and, although we may not be on intimate terms with them, they are not total strangers—words likeruminate, cogitate, and ratiocinate. Others stretch our recognition vocabulary and seem a little exotic—words like ideate, mentate, and cerebrate. Still others seem like creatures from another planet and have to be beamed up by means of a dictionary—words like perpend, noesis, and lucubrate. The total of these single-word synonyms makes a hefty list. Then when we add phrases likepuzzling over, mulling over, stewing over, soul-searching, putting on one’s thinking cap, and using the old gray matter, the list rapidly expands. I gave up my count at around 50.

I suppose these many synonyms might be considered a tribute to the human mind, that extraordinary faculty and supreme treasure of the human species, which distinguishes us from other animals. I flatter myself with the notion that we need so many synonyms in order to delineate the subtle nuances of our rich mental activity. Then, with my head in the clouds, I stumble over the disconcerting fact that the most serious pondering I’ve done recently is whether I’ll have fries with that. Suddenly my list of synonyms seems like linguistic overkill, mere lexicological extravagance or featherbedding. When I consider the mindless sensory overload that characterizes our electronic age, I begin to wonder if we need 50 synonyms for thinking any more than Samoan Islanders need 50 synonyms for snow.

Cultivating habits of reflection, introspection, and quiet pondering has probably been difficult in any age. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, most famous for poems like “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” observes in his book Aids to Reflection:

It is a matter of great difficulty, and requires no ordinary skill and address, to fix the attention of men on the world within them, to induce them to study the processes and superintend the works which they are themselves carrying on in their own minds; in short, to awaken in them both the faculty of thought and the inclination to exercise it. For alas! the largest part of mankind are nowhere greater strangers than at home. [(New York: Chelsea House, 1983), p. 9]

If this observation prompted an “alas” followed by an exclamation point from Coleridge in the early 19th century, it should prompt even greater alarm today, when in an apparent flight from solitude we eagerly eliminate every opportunity to be quietly alone with our thoughts. We are deluged with distractions and opportunities for diversion. Thousands of advertising appeals bombard us each day in the form of newspapers, magazines, circulars, signs and billboards, radio, television, and computers. Cabelas even wants to conscript me into the mighty army of advertising by having me wear their label on the outside of my fleece jacket. We are subjected to background music in every waiting room, restaurant, store, and telephone hold. I have even pumped gas to hits of the 70s. And try escaping television and cell phones at the airport.

Not only is sensory stimulation thrust upon us, we eagerly inflict it upon ourselves. Our homes have numerous handy switches for turning off silence. Our cars, wired for sound (super bass: ka-whump-chugga-whump-chugga-whump), entice us to dash about at the slightest pretext. Cell phones guarantee that we never have to close our mouths and ears for any dangerous interval of time. A generation of children is squandering time in computer games, which may sharpen reflexes but which certainly preclude reflection. They will develop eyes the size of cantaloupes and brains the size of peas, I heard somebody wisecrack. We are sucked into this flux of perpetual sensory stimulation to the point that solitude, if we have the apparent misfortune of stumbling upon it, seems odd and uncomfortable. Our overstimulated lives give point to Pascal’s famous observation that the sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room.

Some of us, unsettled by the overstimulation I am talking about, rush to the cults and cures of exotic or therapeutic meditation. The very name Transcendental Meditation is bound to seem attractively soothing to a population that has never known the privilege of meditating here and now in the midst of life. The Internet is glutted with meditation sites with names like the National Meditation Center and the American Meditation Institute. One of these, for example, the Meditation Society of America, has a “meditation station” on the Web that provides techniques from all traditions throughout the world. It invites us to “become a part of the fastest growing meditation community on the Internet” (https://www.meditationsociety.com). When we join we get a membership package that includes a T-shirt, two CDs, and a newsletter subscription. It seems we can’t even engage in meditation, the most solitary of acts, without a support group. Other sites advertise meditation stools and assorted paraphernalia. There is even a book titled Meditation for Dummies. One site points out that meditation should not be confused with forms of concentration. Concentration focuses “our full undivided attention on a specific aspect of functioning of our mind and/or the body in order to accomplish a certain goal. . . . [Maybe they have in mind things like getting an education, holding a job, sustaining a marriage, or deciding whether there is a God who answers prayers.] In contrast, meditation is an exercise, aiming to prevent thoughts in a natural way, by deeply relaxing the physical body and then trying to keep the mind completely ‘blank’ with no thoughts whatsoever. . . . It seems that our Higher Self does not admit any impurities” (Tom J. Chalko, “Meditation,” Thiaoouba Prophecy [https://www.thiaoouba.com/medit.htm], 1997). I wonder if many of us are doing a pretty good job of keeping our minds blank or in screen-saver mode without the use of specialized relaxation techniques. And I’m afraid my mind goes pretty blank sometimes without causing me to bump into my “Higher Self.”

No, I don’t think replacing mindless sensory overload with mindless forms of trendy meditation is a solution. What is desired is reflection that transpires within everyday lives and that evaluates those lives, assesses values, sets goals, solves problems—in short, that creates examined lives, the only kind that Socrates said are worth living. What is desired is the kind of pondering in the heart recommended repeatedly in the scriptures.

Unfortunately, our society provides little encouragement and few models for quiet pondering. We are celebrity worshipers, and thinkers among us don’t earn celebrity status, partly because they are crowded out by film and rock stars, television personalities, and athletes, but mostly because productive pondering is an inner achievement not on external display. There is, of course, the famous statue of The Thinker, created by the French sculptor Auguste Rodin, but perhaps it is so famous because it stands alone among the myriad statues of other sorts of heroes and celebrities. One would think that if we truly revered thinkers, the figures of more of them would have turned up on pedestals.

Consider a moment the case of The Thinker. “Head in hand, the [familiar] nude figure sits in intense contemplation, twisting awkwardly to rest his right arm on his left knee” (“The Thinker by Auguste Rodin” [https://www.sculpturegallery.com/sculpture/the_thinker.html]). Rodin said of this figure, “What makes my Thinker think is that he thinks not only with his brain, with his knitted brow, his distended nostrils and compressed lips, but with every muscle of his arms, back and legs, with his clenched fist and gripping toes” (Quoted in “The Thinker by Auguste Rodin” [https://www.sculpturegallery.com/sculpture/the_thinker.html]). Who is this thinker anyway? The sculpture was originally conceived as the central figure for a monumental “Gates of Hell” portal, the theme of which was Dante’s Divine Comedy. It was intended to represent the poet Dante in front of the Gates of Hell pondering his great poem. Rodin wrote the following about his creation:

The Thinker has a story. In the days long gone by I conceived the idea of the Gates of Hell. Before the door, seated on the rock, Dante thinking of the plan of the poem behind him . . . all the characters from the Divine Comedy. This project was not realized. Thin ascetic Dante in his straight robe separated from all the rest would have been without meaning. Guided by my first inspiration I conceived another thinker, a naked man, seated on a rock, his fist against his teeth, he dreams. The fertile thought slowly elaborates itself within his brain. He is no longer a dreamer, he is a creator. [Quoted in Joseph Phelan, “Who is Rodin’s Thinker?” (https://www.artcyclopedia.com/feature-2001-08.html), Aug. 2001]

The Thinker didn’t receive its present title until nearly 20 years after it was created.

Unfortunately, this figure has generated thousands of parodies, jokes, and commercial rip-offs. I suppose this is partly because, like the Mona Lisa, it is so famous. But I suspect a deeper reason. The world is not entirely at ease with thinkers. As Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, “Beware when the great God lets loose a thinker on this planet. Then all things are at risk” (Selections from Ralph Waldo Emerson, ed. Stephen E. Whicher [Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1957], p. 172). Moreover, we are slightly puzzled by a muscular thinker. We suffer from a preconception that separates brains from brawn. This shows up in popular culture in the stereotypical distinction between nerds and jocks, bookworms and bullies. Rodin himself sensed the incongruity between scrawny Dante and the muscular figures of his portal. The Thinker, as a sort of nerd with abs of steel, a poet body-builder, slightly bewilders us, and we respond with jokes and parodies. Based on our own mental habits, it may be hard for us to believe someone can think with knitted brow, distended nostrils, compressed lips, clenched fist, and gripping toes. Whether I am right about this or not, mass values and mass media certainly provide neither incentives nor models for constructive pondering.

I’m afraid that most of what is now playing in the theater of my mind is the kind of day-dreaming James Thurber portrays in his famous story “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” You will remember that Walter Mitty is a brow-beaten husband accompanying his wife on a shopping trip. When left unattended he lapses into fantasies in which he is a naval pilot flying through a hurricane, a famed surgeon performing a stunning medical procedure, the greatest pistol shot in the world, an heroic military captain, and a man facing a firing squad with utter calm and disdain. When his domineering wife, who has trusted him to buy the overshoes she insists he wear, says, “Couldn’t you have put them on in the store?” Walter replies “I was thinking. Does it ever occur to you that I am sometimes thinking?” (My World—and Welcome to It [London: Methuen, 1942], p. 18). Walter, of course, was not thinking or meditating; he was “Mittytating.” And much of what passes for meditation among us could more accurately be classified as Mittytation. I confess that I am a master of Mittytation, with a nearly infinite list of credits as writer, producer, director, and starring actor of inner adventures. There is a sameness in plot, but plenty of variety in children rescued, buzzer-beating jump shots swished, ninth-inning homers belted, and award-winning books written. It takes up most of my spare time. When interrupted, I answer as Walter did: “I was thinking.” Similarly, when my wife nudges me in church, I inform her that I was meditating.

Daydreaming is not all bad, of course, even though its self-indulgent forms are pretty pathetic. Our lives would be bland, after all, if bereft of inner fantasies. And in its more respectable, less self-indulgent forms, daydreaming is a vital aid to our creating and planning and self-constructing. Thoreau was correct when he advised, “If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them” (The Portable Thoreau, ed. Carl Bode [New York: Viking, 1975], p. 563).

If daydreaming slips so frequently from meditation into Mittytation, aren’t we much better off reading books? That’s a comforting thought for those of us who love reading. I’m a literature professor. Reading for me is both vocation and avocation. What better way to improve my time, I flatter myself. But occasionally while reading I get the uneasy feeling that if I looked in the mirror I would see a child sucking on a binky. And each time I teach Emerson’s “The American Scholar” I am stung by words like these: “Man Thinking must not be subdued by his instruments. Books are for the scholar’s idle times. When he can read God directly, the hour is too precious to be wasted in other men’s transcripts of their readings” (Selections from Ralph Waldo Emerson, p. 68). Without “creative reading,” Emerson warns, Man Thinking becomes merely the bookworm.

Books are the best of things, well used; abused, among the worst. What is the right use? What is the one end, which all means go to effect? They are for nothing but to inspire. I had better never see a book than to be warped by its attraction clean out of my own orbit, and made a satellite instead of a system. The one thing in the world, of value, is the active soul. [Selections from Ralph Waldo Emerson, pp. 6768)

Continual passive reading can rob the mind of elasticity, and we reduce the chances of having thoughts of our own by using books as pacifiers. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer noted the paradoxical nature of balancing knowledge and thinking:

As the biggest library if it is in disorder is not as useful as a small but well-arranged one, so you may accumulate a vast amount of knowledge but it will be of far less value to you than a much smaller amount if you have not thought it over for yourself; because only through ordering what you know by comparing every truth with every other truth can you take complete possession of your knowledge and get it into your power. You can think about only what you know, so you ought to learn something; on the other hand, you can know only what you have thought about. [Essays and Aphorisms (New York: Penguin, 1970), p. 89]

Reading can be an aid to thought, but only if it is thoughtful reading—what Emerson called creative reading. Even scripture reading, in order to be truly edifying, must be an exercise of the active soul. The scriptural admonitions are always to search, ponder, and meditate, and not simply to read.

I have focused on the difficulty of cultivating the habit of quiet reflection, which is an art as well as a habit, an art of which every person should be master, for if we are not thinkers, to what purpose are we human beings at all? Life consists, after all, in what we are thinking each day, and we should value our days by the number of clear insights we have gained. To appreciate the difficulty of focused pondering, try this thought experiment. Select a subject or problem and, with watch in hand, try to focus your mind upon it unswervingly for a determined number of minutes. The first time I attempted this I aimed for five minutes. Forty seconds later I was wondering why my watch was in my hand. Granting that your power of concentration may be greater than mine, you will find nevertheless that within seconds the random images and chance associations that form the currents of our stream of consciousness have swept you off course. Contemplation requires an inner check, a withdrawal from that mental-emotional flux long enough to reorient oneself and set a new course.

Do I have any suggestions for cultivating the art and habit of reflection? Only a meager few. First, I recommend pondering, at least occasionally, in words—in words in the sense of self-consciously selecting words and formulating sentences in a silent inner discourse. Pose questions to yourself and propose answers, hearing the sentences in your mind, revising them for clarity and precision and even eloquence. This requires focused concentration that reduces the swervings and deflections I described in the thought experiment I just spoke of. It gives order and continuity to our reflection and promotes a feeling of companionship with our inmost self, a more vivid awareness of the reasoning, creating voice within. This deliberate process of articulation becomes discovery as well as expression. More than one writer has said, “I don’t know what I think until I have written it down.” Something similar holds for inner composition as well. Words do not merely express our thoughts, they make our thoughts.

Second, I recommend pondering about words. Accustom yourself to reflect on the words you hear and read and use—on their derivation and history, their denotation and connotation, their plasticity to context. Don’t take words for granted. Many common words serve multiple purposes, acquiring definite meaning only when placed in particular sentences. Thought and often careful reflection is required to interpret the specific instance. Many cases of fuzzy thinking, misunderstanding, indecision, and argument can be resolved by thoughtful clarification of terms. “For if words are not things,” says Coleridge, “they are living powers, by which the things of most importance to mankind are actuated, combined, and humanized” (Aids to Reflection [New York: Chelsea House, 1983], p. xix).

Third, I recommend alert contemplation of the objects and event around us; their significance is often not immediately apparent. A cartoon in the New Yorker once portrayed the Red Sea parted and two Israelites walking across in conversation. They were participating in one of the greatest faith events in history, an event that would be rehearsed forever as evidence of God’s power and providence, an event that is part of the glue that has held the Jews together as a distinct people down through the ages. One of the Israelites says to the other, “Ick, I think I just stepped on a fish.” Don’t be oblivious to the significance of what is going on about you. In 2 Ne. 4:16, Nephi says, “Behold, my soul delighteth in the things of the Lord; and my heart pondereth continually upon the things which I have seen and heard.”

My most important recommendation is that we do not flee from solitude but embrace it jealously. It is the nursery of thoughts and aspirations that benefit society as well as the individual. Solitude is not to be feared. Matt. 14:23 tells us: “And when he had sent the multitude away, he went up into a mountain apart to pray, and when the evening was come, he was there alone.” He was there alone. As a matter of fact from his 40-day fast in the wilderness to his death on the cross, when he cried out “My God, why hast thou forsaken me” (Matt 27:46), Christ was, in significant ways, alone. And so are we. Being alive means being in a body—a body separated from all other bodies. We can commune with others in important ways, but ultimately we are alone. It is our destiny. This is both the burden and benefit of our existence. It is what we do with our obligatory aloneness that matters. Only a creature with an impenetrable center in himself or herself is truly free and strong. We must not confuse solitude with loneliness. Loneliness is a terrible thing and all too common. It is endemic in our society and billions of dollars are spent to combat it. Much of the sensory overstimulation I mentioned is a response to the fear of loneliness. But ultimately, loneliness is conquered only by those who understand the benefits of solitude, the most important of which is quiet reflection—the examined life, the active soul. These alone are of lasting importance in a world of transience and triviality. I cite Emerson once again:

We dress our garden, eat our dinners, discuss the household with our wives, and these things make no impression, are forgotten next week; but, in the solitude to which every man is always returning, he has sanity and revelations, which in his passage into new worlds he will carry with him. [Selections from Ralph Waldo Emerson, p. 273]

It is not what we reflect upon that is so important as the habit of reflection itself. Even pondering small things can have large consequences, whether it is Newton musing on the fall of an apple, Galileo contemplating a swinging censer, or a 14-year-old New York farm boy pondering a single verse in the New Testament. Moreover, ideas evolve and conclusions melt away in the heat of new experience. Few matters are settled completely or manifest in their fullness once and for all. But the impulse of the active soul toward quiet reflection remains the perennial source of personal fulfillment and communal benefit.

Stephen L. Tanner is BYU’s Ralph A. Britsch Humanities Professor of English. As the 2004 Karl G. Maeser Distinguished Faculty Lecturer, Tanner delivered this forum address Oct. 26, 2004, in the Marriott Center.