David G. Long, BYU associate professor of electrical and computer engineering, knew his work on the design of one of NASA’s newest satellites would pay off, but he wasn’t sure it would be so soon.

On one of the QuikScat radar imaging satellite’s first passes over Antarctica, it transmitted images to Long revealing an iceberg the size of Rhode Island. The iceberg broke off the end of Antarctica’s Thwaites glacier in 1992. In 1995, it broke in half but was being tracked on a regular basis until scientists lost it earlier this year. Long’s discovery of the iceberg allowed authorities to make appropriate warnings for shipping lanes.

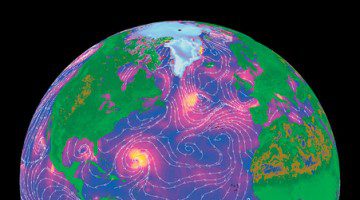

The QuikScat satellite, launched in June, is orbiting 500 miles above the earth, circling the planet every 100 minutes and sending back high-resolution radar images of 90 percent of the earth’s surface every 24 hours. Rather than producing photo images of clouds, the device “sees through” cloud cover, bouncing radar waves off the earth’s surface to provide a measure of “surface roughness.” The data distinguishes between different types of trees and between snow and ice. Over water, the device records tiny waves that reveal wind speeds and weather patterns.

Long’s BYU student researchers can take credit for writing some of QuikScat’s computer processing code and for creating reference tables that will aid in interpretation of the data. After the QuikScat launch, Long and his students worked withNASA scientists to help calibrate the device and check its reliability. It was during this period that Long discovered the iceberg.

The iceberg is expected to break up soon because it is drifting into warmer waters. “We will be able to watch the iceberg’s breakup for the first time with daily radar observations and better understand the effects of ocean winds and climate on melting polar ice,” Long says. “The polar regions play a central role in regulating global climate, and it is important to accurately record and monitor the extent and surface conditions of Earth’s major ice masses.”